2024 Overlooked Risk: Digital Service Taxes and International Frameworks a Viable Solution for Expanding the Tax Base?

As the world economy is becoming more digitized, the tax system is facing a growing challenge, but not every country and business has been aware of the curse. Traditional rules governing taxation are only applied to businesses with a physical existence in an economic territory, so digital goods and services which may not have a tangible presence are not necessarily being taxed. This creates a controversy over whether the digital sector is paying a fair share of taxes. Meanwhile, as more economic activities are moving online, the economic importance of the online sphere has grown relative to that of the physical world. Therefore, the current legal loopholes in the tax system have increased states’ vulnerability to tax base erosion, which poses a latent threat to their long-term fiscal stability.

The digitalization of business models points to a need for a new type of tax in response to the unstoppable trend of digitalization. Some countries like the UK and Turkey have embraced the option called digital services tax (DST), which refers to taxes on gross revenue derived from a variety of digital services.

While DST can certainly widen the tax base by covering digital commodities that have been ignored by traditional taxes, the introduction of DST can hardly avoid problems. The online world is ultimately a virtual sphere with no clear geographical boundaries, so traditional tax concept jurisdictions of tax revenue may not apply to the digital sphere. Customers from a state with DST may be consuming virtual goods and services provided by companies outside the state. Alternatively, the companies may be collecting data from consumers from other countries to generate profits. Under imperfect information, these companies, despite offering products to foreign customers, may not necessarily be aware that they could be subject to taxation of another state. Such information and compliance issues can put them vulnerable to additional penalties, thus arousing controversies over the jurisdiction of tax revenue.

In light of the escalating threat of such risks and the uncertainty over the fiscal space, this report aims to explain how the digitalization of the world economy will impact the fiscal stability of both developed and developing countries in the foreseeable future. It also provides several recommendations for both the governments and the market to navigate the risk and prepare for what lies ahead.

In addition to the DSTs in the U.K. and Türkiye, there are other multilateral initiatives which set out to broaden the digital tax base and ensure fair tax is paid by multinational enterprises (MNE).One such initiative, and perhaps one of the most influential of its kind, is the OECD’s Inclusive Framework on Base Erosion and Profit Sharing (IFBEPS). The IFBEPS comprises of two pillars; (i) giving taxing rights to jurisdictions where MNEs conduct business even if MNEs do not have a physical presence in that jurisdiction, and (ii) ensuring that MNEs with over EUR 750mn in revenue pay a minimum tax rate in the jurisdictions where they operate physically even if they do not have business within that jurisdiction. The IFBEPS is due to come into effect across the 137 member countries at some stage later this year.

Although the IFBEPS is in so many ways a crucial initiative to tackle digital tax avoidance, it has two limitations. The first is that the vast majority of member countries are Western democracies, barring some exceptions in Africa and Asia. The second is that the IFBEPS does very little to actually boost bottom-up issues in the digital economy, namely participation. Nevertheless, both of these limits sit largely outside of the IFBEPS’ remit, though both are pertinent observations. For one, it remains to be seen if the adoption of IFBEPS pillars might push MNEs to operate in states that are not signatories to the IFBEPS to limit tax burden although at a potential risk of a reduction in human capital or moving costs. Secondly, a lack of bottom-up approaches means that whilst large multinationals would have more tax exposure plenty of small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) may not be impacted as significantly, especially in jurisdictions with large informal economies or tax delinquency rates. For those countries - with large informal economies and tax delinquency - IFBEPS might only increase overall tax revenues marginally without robust bottom-up approaches.

Fortunately there are examples of how such countries can go about increasing bottom-up participation. One such example is South Korea’s ‘Coin-Less’ society which aims to increase card payments and usage. The premise of the programme launched by the Bank of Korea (BoK) is to return change to cash-paying customers to prepaid debit cards through arrangements made between businesses, POS providers and debit card issuers. The logic of the programme is thus to highlight the convenience of card payments with respect to cash.

Figure 1: Bank of Korea ‘Coin-Less’ Scheme, taken from World Cash Report

Of course, a limitation to the implementation of such schemes is that they would probably only be implemented on a voluntary basis. Nevertheless, they could go a long way in promoting digital payments in the long-run in tax jurisdictions with low consumer digital payment usage and informal economies.

Nevertheless, DSTs and the IFBEPS mark a good first step in expanding the tax base to cover digital services but also have the potential to be the foundation for policies similar to the BoK’s ‘Coin-Less’ scheme, which could go a long way in combatting the informal economy by increasing participation in the digital economy. For this reason, the roll-out of the IFBEPS in 2024 will be crucial for expanding global tax bases into the digital space.

Regional Inequality in the EU: A Risk to Enlargement?

The European Union’s enlargement policy “aims to unite European countries in a common political and economic project”. According to the European Parliament, enlargement “has proved to be one of the most successful tools in promoting political, economic, and social reforms”. Indeed, this is largely true: EU citizens are able to move freely for business, education, and leisure within the bloc; the EU has a robust uniform trade strategy, and above all, the EU has largely consolidated peace in Europe since its inception.

However, according to Emil Boc, the EU’s free movement policy suffers from a serious macroeconomic limitation: brain drain. The former Romanian prime minister – now mayor of Cluj-Napoca – has been actively raising awareness of this issue. Emil Boc recognises the issue is at the intersection of regional integration and national-level macroeconomic conditions. Simply put, the fundamental right to freedom of movement within the EU and adverse macroeconomic conditions in various Member States lead to talent from those Member States leaving to wealthier Member States or indeed leaving the EU altogether. A 2018 report by the European Committee of the Regions shows that the vast majority of ‘sending regions’ can be found in Southern Europe and in Eastern Europe, whereas ‘receiving regions’ were largely concentrated in Northern Europe and most of Italy. This iterates the systemic nature of the problem within the EU. Although there is yet no formal policy dedicated to addressing brain drain within the EU, the issue has gained salience over the last few years. Emil Boc was the Rapporteur for an official opinion published by the European Committee of the Regions, calling for a local government approach to tackle the issue. Similarly, over the last year, the European Commission has formally recognised the issue.

An intra-European brain drain may not seem at prima facie as a policy issue that ought to be addressed at the European level, it must definitely is. The reasoning is two-fold: firstly, brain drain means that periphery countries and ‘sending’ regions do not grow at the same pace as wealthier countries or regions which can drive euroscepticism. Secondly, for prospective countries looking to join the EU, the prospect of having talented members of the workforce emigrate might hamper enlargement.

Perhaps the second risk is more hypothetical than the first, the link between poor macroeconomic conditions (i.e. push factors for talented workers) and anti-EU sentiment and poor integration is well-documented in ‘sending’ regions and countries. Indeed, it is not a coincidence that Hungarians, Italians, Poles, and Slovaks have all elected outspoken Euroskeptics as head of government – for a long time those countries faced stagnating economic conditions and brain drain – now their governments are willing to challenge Brussels on core elements of foreign and internal policies.

Professor Sunak’s Education Policy: Legitimate Reform or ‘Weak’ Intervention?

On July 17 2023, Prime Minister Rishi Sunak unveiled plans to limit students enrolling to so-called ‘rip-off’ university degrees. He justified this policy position on the basis that 30 per-cent of university graduates in the U.K. did not find high-skilled employment nor did they enter further study. Perhaps more worrying, as the Prime Minister explained, a fifth of all university graduates in the U.K. would be financially better off not having gone to university.

This latter point is particularly accentuated by the relatively high cost of education at public universities in the United Kingdom with respect to the rest of Europe. But, even in a hypothetical scenario where the most part of tuition costs were absorbed by taxpayers, this would not change the first point of concern: that British universities are not sufficiently training students to enter the high-skilled workforce (which, according to government guidelines, can be many types of work).

Justification and Opposition

Arguably, upskilling students to enter the workforce is the primary telos of higher education institutions. Therefore, if those institutions are failing to perform that function effectively whilst indebting young adults and diverting tax revenues to inefficient institutions, it might be that case to increase the standard of students entering higher education by increasing the skills young people acquire in their formative years, as well as diversifying the post-16 pathways for those students who might not go to university should Sunak’s proposal come to fruition. Indeed, this is what much of what Sunak’s recent career as a politician has been dedicated to: as Chancellor of the Exchequer, he approved £1.6bn funding for T-level qualifications and since taking office, his government has announced a clamp down on “anti-maths” culture by extending compulsory mathematics in post-16 secondary education. However, with regards to the ‘rip-off’ degree crack down, there are still a lot of things which have yet to be defined. Specifically, the criterion for a ‘rip-off’ degree and how would those criterion be reviewed in a way that reflects the future of the labour market, rather than the past and present.

For example, if we consider a BSc in XYZ that today has very little employment prospects, but in 5 years’ time, that degree has significantly better labour market performance for graduates – how would British universities by able to catch up with international institutions that might have greater expertise in that specific field? There is also the question of discriminating against specific subjects or disciplines – namely humanities or social science. It is perfectly justifiable to intervene to increase the quality of higher education, but perhaps an alternative approach could be to place a requirement for university departments to have teaching staff with more technical diversity to avoid academic and pedogeological groupthink.

An Ulterior Motive for Reform?

Although a lot of administrative questions remain to be answered in the coming months, the crack down on ‘rip-off’ degrees could remedy a slightly different malaise. That is: declining pension replacement rates and increasing youth unemployment. In 2020, pension replacement rates were around the 58 per-cent mark, making U.K. pension payouts among the 12th lowest in the OECD. Effectively, pensioners on the State Pension lose nearly half of their contributions when they reach qualifying age. As stated by the Office for National Statistics, “[pension] payments by the government for unfunded pensions are financed on an ongoing basis from National Insurance contributions and general taxation”.

So, if the young people entering the workforce decreases (and if a fifth of those young people enter the workforce with substantial debt) at a faster rate than people reaching pension age, the overall pool for unfunded pensions will be proportionally smaller for each individual pensioner. Indeed, in 1990 just under two-thirds of people aged 15-to-24-year-olds were in some form of employment. That number is now around the 50 per-cent mark, which is still better than the average employment rate for that age group in the G7, OECD, and European Union, but the 50 per-cent figure is substantially lower than countries like the Netherlands where three-quarters of 15-to-24-year-olds are employed in some way. Furthermore, Table 1 shows that the proportion of people of working age will decrease slightly with respect to the dependent population between now and 2050.

Table 1 - U.K. Population by Age Group. 2023 data available here, 2050 data available here.

This is a demographic challenge that the UK, as well as the rest of Western Europe, will be contending with more and more as the years go by. Further, the aging population problem will require some sort of unpopular policy reform to European welfare states. As Macron has learnt in France, even something as simple as raising the retirement age can send a leading economy into calamity. In the U.K., the State Pension age has already risen to 67 for both men and women. A further increase to 68 may be on the cards, but Rishi Sunak’s education policies suggest the British government is trying to ameliorate the problem by increasing the employment prospects of the youngest earners rather than narrowly focusing on improving the fiscal efficiency of British universities.

Summary and Outlook

A lot of the practicalities of Rishi Sunak’s push to crack down on ‘rip-off’ degrees are yet to be seen. Concern and opposition are justified and necessary but claims that the proposal is an “attack on aspiration” are a bit far-fetched at the moment. Not least because the option of a decent State Pension is a public service worth protecting and maintaining, but substantially because little is known for the moment about this policy. Thus, until postulation becomes policy, criticisms are as constructive as they are speculative.

That said, Rishi Sunak’s push for education reform is warranted not just on pedagogical grounds but also for the sake of a crucial welfare service. However, the Conservative government must also avoid – by intent or miscalculation – to create elitist bifurcations between academic and technical qualifications.

The ‘Biden-McCarthy Deal’: Is America’s Business Still… ‘Business’?

On June 3 2023 President Biden signed into law the ‘Biden-McCarthy Deal’, formally known as The Fiscal Responsibility Act (FRA; 2023) or H.R. 3746. The Act is the result of 6 months of debate in Congress and Congressional Committees, before Speaker of the House - Kevin McCarthy - and Joe Biden managed to strike a deal. Biden’s signature quelled his administration's second debt ceiling ‘crisis’, the first having occurred in late October 2021. The debate around the FRA highlights what is becoming a recurring theme in U.S. economic policy: ideological differences over non-economic policy leading to increasing economic policy uncertainty and ‘crisis’ events. For this reason, The FRA (2023) is being championed as a crucial moment for U.S. bipartisanship.

What the FRA Tells Us About Politics and the Economy

The FRA effectively suspended the debt ceiling until January 2025. Section 401(c)(1) gives the legal basis for much of already legally approved legislature and expenditure to be carried out, whilst Section 402(c)(2) prohibits The Secretary of the Treasury from issuing obligations until January 1 2025 “… for the purpose of increasing the cash balance above normal operating balances”. It is worth noting that The FRA is a long legal document, but Section 401 demonstrates the broad partisan compromises: the Biden administration and the Democrats can carry out their approved reforms and policies, and the Republicans got some of what they wanted in terms of limiting drastic money supply increases, quelling concerns of potential inflationary pressures arising from Biden’s policies.

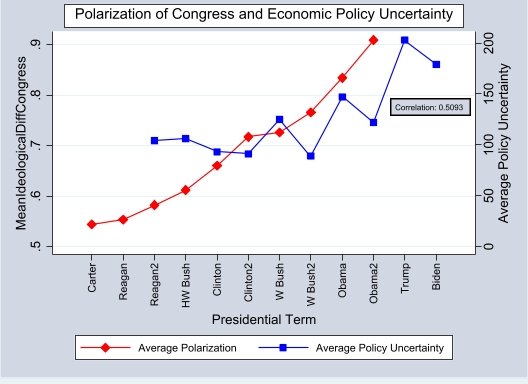

Rana Foroohar, Global Business Columnist and Associate Editor at the Financial Times, highlights that much of the debate around The FRA has been largely hung up “… on highly political issues such as defunding the Internal Revenue Service”. This draws attention to the fact that decades-long increases in political polarization is damaging the ability of the legislative branch to devise stable and predictable economic policies, which leads to recurring self-imposed debt ceiling ‘crises’ and government shutdowns that hamper investor confidence. Figure 1 visualises this increasing polarization and economic policy uncertainty:

Figure 1: Mean Ideological Difference (Polarization) of Congress and Average Economic Policy Uncertainty

The red curve uses data from Brookings to demonstrate the average ideological differences between both sides of the isle in Congress. The values used in Figure 1 were obtained by finding the difference in means of each legislature and plotting them against the corresponding term of the serving executive. Likewise the blue curve showing average economic policy uncertainty is a four-year average, corresponding to the four-year terms of the executives starting from the Carter administration. This data is obtained from Economic Policy Uncertainty (EPU) – a thinktank that specialises in political risk indices and indicators. The economic policy uncertainty index methodology comprises three components: automated analyses of media reports, the Congressional Budget Office’s publication of expiring tax code provisions, and expert sentiment around inflation and government purchases.

Of course, the data are descriptive and the positive correlation – 0.5903 – is not in and of itself indicative of any evident causal effect. Nor is data available for every administration. However, the challenges of recovering financially from COVID-19 and heightened political tensions at the qualitative level are a worrying sign that polarization is permeating economic policymaking. January sixth-esque events are not common occurrences in American history, and even shutdowns and risks of default have only become commonplace since the late 1970s. So if in 1925 the “chief business of the American people [was] business” then in 2025 the chief business of the American people will be politics.

Outlook for 2024: Yet Another Consequential Election

With the next potential debt ceiling ‘crisis’ set to come about in 2025, the eventual winner taking office after the presidential election in 2024 will have little time to get to work. Amid the ever-growing list of Republican candidates, former president Donald Trump and the Governor of Florida Ron DeSantis appear to be front-runners in the race. Asa Hutchinson is the next high-profile GOP candidate. On the other side of the aisle the incumbent Biden and Robert F. Kennedy, alongside Marianne Williamson.

At this stage it is still unclear what any of these candidates’ policies might look like considering there is still time to go until campaigning officially starts and intra-party housekeeping finishes. Of the candidates, the two most recent presidents do not have much to boast about economically. On the one hand, Trump inherited an economy at the apex of a growth trajectory and benefitted substantially from that fact prior to the pandemic. On the other hand, Biden inherited an economy with a post-COVID hangover and a war in Europe. Crucially, Biden is also having to contend with his counterpart in Beijing pursuing expansive foreign policies, flirting with de-dollarization.

Certainly, whoever is in office by February 2025 will have to navigate a turbulent macroeconomic environment domestically and internationally – as will transnational corporations and investors. “Political risk”, for corporates and investors, is becoming less of a concept attached to far-flung economies and is increasingly becoming a concept attached to what were once ‘stable’ economies in the West. The businesses who can best anticipate this will be the ones to best adapt to the global macroeconomic environment in the not-so-distant future.