The Dual Crisis in Sri Lanka: A Country in Turmoil

The devastating impact of the COVID pandemic, compounded by the adverse economic consequences of the war in Ukraine, have brought many countries in South Asia to the brink of dire economic realities at home. The island nation of Sri Lanka is a case in point. The past few months have been tumultuous for the people, as well as the political leadership, of the country. Facing a dual economic and political crisis, the country is now reeling under immense economic hardships and critical shortages. The government, however, is similarly focused on rectifying years of poor economic policy. The foreign exchange reserves have been greatly depleted, Colombo has defaulted on its debt repayments, and inflation peaked as high as 39.1% in May 2022. With a change of the guard on the 13th of May and the appointment of Ranil Wickremesinghe as the new Prime Minister (PM), it appeared that the country was beginning to navigate through its ongoing turmoil. Despite the hope that Sri Lanka is stabilising, this reality remains distant until concerted efforts are taken to target the economy’s structural impediments, and undo ethnic animosities.

The fallout of debt dependency

To get a clear idea of the factors augmenting the nation’s economic crisis, it is imperative to look at two aspects. Firstly, Sri Lanka’s relationship with debt, and secondly, the ad-hoc and erratic policy making since 2019. While the economy’s stock of foreign debt has fallen from 50% in 1995 to 30% in 2014, the post-civil war growth, though brief, has been fuelled by public debt projects. This public debt has, in turn, been sourced through international sovereign bonds (ISB), as well as loans from major bi-lateral partners such as China. The debt levels, however, have begun to rise rapidly since 2014, with 2019 witnessing a debt to GDP ratio of 42.6%. This has been a consequence of the ISB repayments that were issued between 2015 and 2020, roughly $6.7 billion dollars. After its switch from a low-income to a lower middle-income country in 1997, Colombo lost access to the concessionary loans that it was able to repay over a long period of time, which has destabilised its debt (Table 1). Between 2005 and 2015, China was the leading source of developmental assistance and invested heavily in infrastructure in the civil war’s aftermath.

Table 1

Source: IMF Country report

Table 2

Source: Central Bank of Sri Lanka

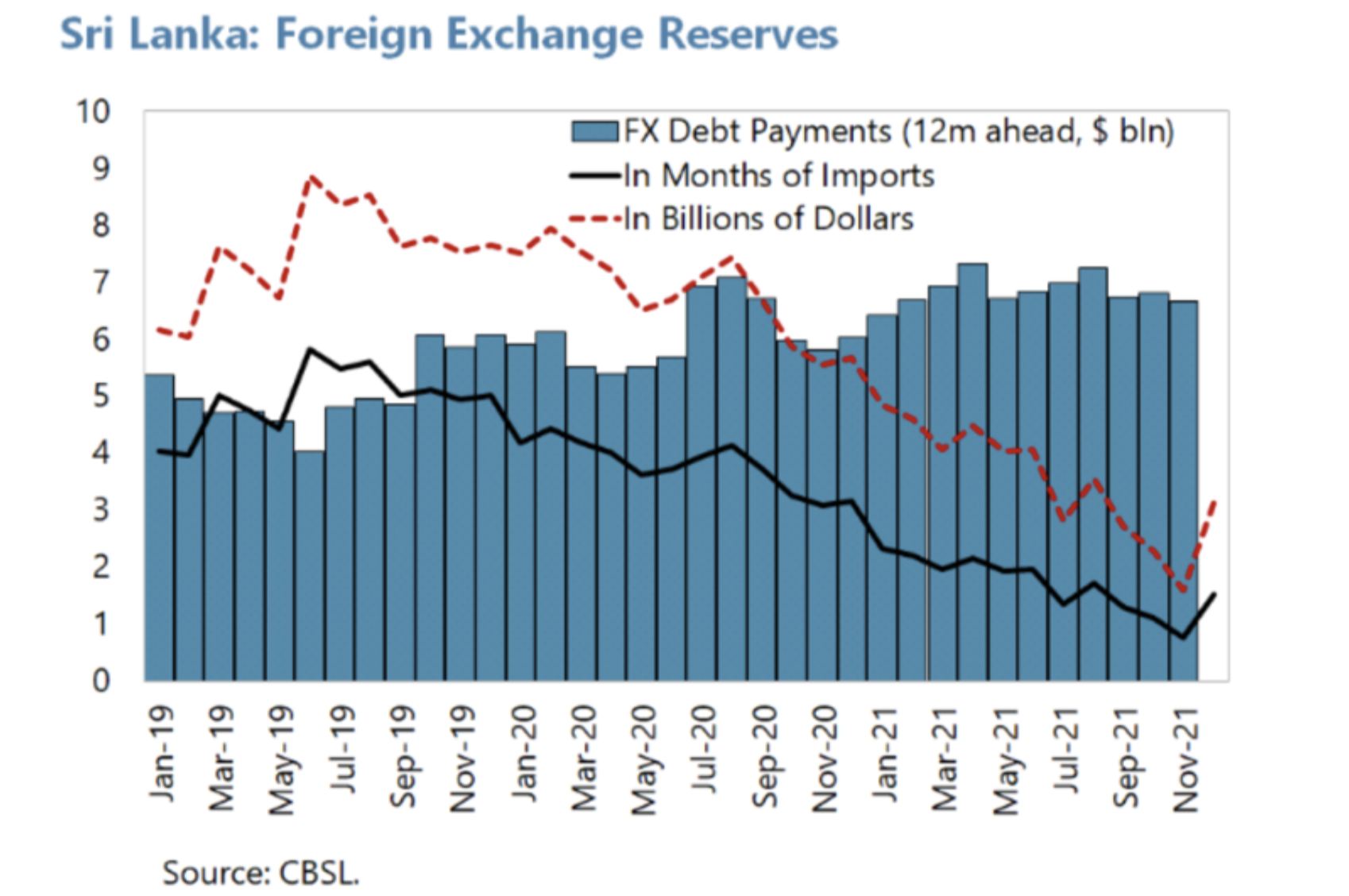

The country’s dependency on borrowing has precluded the leadership from undertaking genuine reforms to target the structural impediments to growth in the country; low trade, low FDI, declining tax revenues, and a failure to diversify export destinations and sectors. It is because of this deep ‘macroeconomic and political problem’, that the country is caught in a vicious cycle of increasing foreign debt and low currency reserves, yet without the political will to reform the structurally unsound economy. (Table 3)

Table 3

Source: CBSL.

Rolling Political Turmoil

After ruling the country for close to a decade, Mahinda Rajapaksa was defeated in the 2015 presidential elections by a former minister in his administration, Maithripala Sirisena. Elected on the premise of ushering in good governance and gaining from the ‘anti-Rajapaksa' sentiment, especially amongst the minorities, Sirsiena appointed Ranil Wickremsinghe as the Prime Minister of the National Unity Government (NUG). This was a coalition of opposition parties, initially for 100 days but subsequently extended for two years. A formal Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) was signed by the Sirisena led, Sri Lanka Freedom Party (SLFP) and the United National Party (UNP) of Ranil Wickremsinghe, after the latter won the most seats in the parliamentary elections. The coalition, however, hit a roadblock when Sirsena abruptly sacked the incumbent PM and replaced him with Mahinda Rajapaksa, pushing the country into a political crisis. While Wickremsinghe was reinstated as the PM after the Supreme Court passed an order, the power struggle dented the already dwindling reputation of the coalition. While the ‘tug of war’ between the President and the Prime Minister hadn’t fully subsided, the country was rocked by the April 2019 Easter bombings, which killed more than 250 people. The government was blamed for failing to act on intelligence on the attacks and the aftermath of the attacks saw increased polarisation in the country, with suspicions between the Muslims and the majority Sinhala communities compounding even further. The electorate lost faith in the government and its ability to ensure the nation’s security, clearing the way for the Rajapaksa brothers to fashion their campaign on the plank of hard-line national security. The Sri Lanka Podujana Perumana party (SLPP), therefore, emerged victorious by a large margin in both the presidential and parliamentary elections. Building upon his ultra-nationalist rhetoric, the Gotabaya Rajapaksa administration soon took major decisions on the fiscal and agricultural policy front, the consequences of which the nation is still grappling with.

(Un)Sound economic policy?

In an attempt to reinvigorate GDP growth, the administration reduced the rates of taxation. The Value Added Tax (VAT) was slashed from 15% to 8%, while the 2% Nation Building Tax on goods and services was done away with ( refer Table 4). According to the International Monetary Fund (IMF), these actions led to a 2% reduction in the GDP and resulted in the suspension of the IMF’s programme which began in 2016. The cuts led to a loss of around 1 million taxpayers, with the number of businesses paying VAT falling from 29,000 in 2019, to just 8300 in 2020. Many investment agencies downgraded Colombo’s sovereign debt rating, as a consequence of which it lost access to international financial markets. The foreign reserves which were at $8,864 million in June 2019 fell to $2,361 million in January 2022. While the ex- Finance Minister Ali Sabry did acknowledge that the tax cuts were a ‘historic mistake’, the blame was still outsourced to the pandemic.

Table 4

Source: IMF Country report

Moving forward, the government followed this by borrowing from the central and commercial banks, which led to a major increase in the money supply (42% from December 2019- August 2021). With the onset of the pandemic, and a stark reduction in tourist inflow, the already feeble economy was put under further pressure. The then Central Bank Governor, Weligamage Don Laksham, assuaged fears about Sri Lanka’s debt sustainability and argued that an increase in domestic debt can act as an alternative to their lack of access to foreign markets. This was continued by his successor, resulting in fewer and fewer people being willing to buy treasury bills. Public debt during this time rose from 94% of the GDP in 2019 to 119% in 2021.

Alongside poor macroeconomic governance, the government’s sudden decision to ban the import of chemical fertilisers in April 2021 greatly exacerbated the nation’s plight. Enacted to curb the harmful effects of agrochemicals and to arrest the fall in FOREX reserves, the ban has had an adverse impact on the agricultural yield, specifically tea ($425million losses), pushing the state into a more vulnerable position, whereby it has been forced to import rice from Myanmar and China. Furthermore, the policy led to a balance of payments crisis, and by the time the government rolled it back in November the damage to the economy had already been sustained. In January, Ajith Nivraad Cabraal, the Central Bank Governor, expressed confidence in Colombo’s ability to repay its 2022 debt commitments ($4.5 billion in total), beginning with the $500million bond which was due in the first month. Riding on the high horse of the country’s untainted repayment track record, he asked the people to not heed foreign economists or the IMF’s advice on the economy, going as far as to caution against IMF bailout packages which were not a ‘fix-all solution’. While his critique of the bailout and Colombo’s mixed experience with the organisation wasn’t completely ignorant, his hope of adopting a ‘comprehensive plan’ to address the issue of dwindling FOREX reserves were shattered with the Russian invasion of Ukraine. Commodity prices skyrocketed in response to the disruption in supply chains. Simultaneously, there were prolonged power cuts and citizens queuing up for essentials.

Table 5

Source: IMF country report

Redefining the Sri Lankan identity: The role of the ‘Gota go gama’ protests

The combined economic and political fallout from the past few years, combined with the external shock from the Ukraine war, has culminated in anti-government demonstrations. The protests against the government began in March with the Galle Face beach in Colombo emerging as the nucleus of the demonstrations, a ‘secular shrine of democracy’s regeneration in Sri Lanka’. The main demand of the protestors was for the removal of President Rajapaksa from his post, and to hold him accountable for pushing the country into chaos and uncertainty. While ministers from the Cabinet and the central bank governor have all resigned, the President has remained, unwilling to be seen as a “failed” leader. The demands soon snowballed from ameliorating the existing economic conditions, to holding the government accountable for larger issues affecting the country. These have typically manifested around the powers of the executive presidency, and the need to reconcile the inter-ethnic strife that has defined the nation since its inception.The country was embroiled in a civil war for close to 26 years, from 1983-2009, between the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE) who wanted to establish a separate state for the Tamil minority (approxiamtely 11.2% as per the 2012 census), and the Sri Lankan government. The LTTE was finally defeated in 2009 when its senior leadership was eviscerated and the civil war was declared to be over.

While some view this collective fight against the government at present as a means of removing the historical distrust between the different ethnicities, minorities have been cautious in regard to showing public opposition to the state. Reminding them of the inhumane conditions that they lived through during the civil war, the Tamils are unsure of lending their full support to the movement. While efforts to publicly commemorate the civil war at Galle Face were welcomed by them, there is still a little hope that the protests will lead the way for a “...prosperous Sri Lanka, without any racial, religious or language differences, tearing down the ethnocratic structure of governance that prevails since Independence”.

The opposition and the Bar Council of Sri Lanka have also been pushing for the removal of the 20th Amendment to the constitution and the formation of a government based on consensus. But beyond hollow calls of respecting people’s grievances and their right to protest, the government castigated the protestors as ‘organised extremists’ deliberately maligning the country, calling in the military and imposing a state of emergency which was only rolled back after a few weeks.

The mostly peaceful protests turned violent on 9th May after a speech by the ex-PM Mahinda Rajapaksa when his supporters attacked the anti- government demonstrators. The resulting flare ups led to looting and arson, with 150 people injured and approximately 2400 arrested. The Rajapaksa memorial in Medamulana was brought down, a symbolic attack on Sri Lanka’s most prominent family.

Leadership change to reach an elusive stability?

While refusing to vacate his position as President, Gotabaya Rajapaksa chose Ranil Wickremesinghe as the PM to appease the anti-government protests. For the President, who recently expressed his conviction to finish his term in office, the motivation behind replacing the PM was to placate the disgruntled population and ease pressure on his government. Alongside this, it also acted to signal to the international community that stability was on the horizon. But not everyone viewed it favourably. Disappointed at not being consulted before the choice was made, the Samagi Jana Balawegaya (SJB) leader, Sajith Premadasa, and other notable politicians refused to be a part of any interim government that was formed. Thus, even with a changed PM, and while the PM has put emphasis on saving the country as opposed to just family, the near absence of opposition party leaders in the Parliament makes the passage of reforms very difficult.

After assuming office, Wickremesinghe detailed his assessment of the economic situation and the remedies adopted or in the process of adoption by the state. Apart from the economic crisis, the country is also facing two major constitutional issues as per him- the passage of the 21st amendment and the complete abolition of the office of the executive presidency. Placing emphasis on the need to strengthen the Parliament, the PM proposed the establishment of new committees on monetary affairs and oversight while working to dilute the powers given to the President through tabling the 21st amendment, which was presented in the Parliament on 6th June. Aimed at overwriting the 20th amendment passed in 2020 which gave unfettered power to the President, the draft has received criticism from all quarters. In an interview with Bloomberg, the President expressed his discomfort at the idea of having a mixed system, arguing that either the executive presidency be abolished altogether, or a full Westminster style parliament adopted in the country. The complete abolition of the executive President has been a long term demand of the opposition and the civil society but something that all subsequent governments have struggled to respond to.

Bracing the people for the next few months, the PM also detailed the financing needs of the country. According to the government, Colombo will need a total of $5 billion for basic expenses, $1 billion as reserves, $ 3.3 billion for fuel imports, $ 900 million for food, $ 250 million for cooking gas and $ 600 million for fertilisers. So far, the country has received funding from the IMF, the Asian Development Bank and bilateral support through lines of credit from China, India, Bangladesh, Japan, and Indonesia. Confident of the support that Sri Lanka’s foreign allies can give the country, the PM also envisioned the formation of a foreign consortium for financial assistance. While refusing to seek assistance from the IMF in the beginning, it is now in talks with the group for a Rapid Financing Instrument as well as an Extended Fund Facility. The government suspended its external debt repayment schedule on 12th April to restructure it in a manner consistent with the principles of the IMF. In the last meeting on 24th May, the Fund asked Colombo to initiate reforms focused on two elements; a tightening of monetary policy and an increase in the rate of taxation. It recommended the expansion of social safety nets and a targeted approach to mitigate the ‘macroeconomic vulnerabilities’ of the country. In response to this, the government has appointed financial and legal advisors for restructuring the debt.

The new government will also present an interim budget to the Parliament by the end of this month. With its focus on public welfare and its target population, the ‘economically weaker sections’, the budget will curb unnecessary government spending while prioritising the export, tourism and construction sector. The resources will be diverted from infrastructure to relief work, with relief packages increasing from $350 million to $550 million. Loan waivers for farmers owning less than 2 hectares of land, an increase in VAT from 8% to 15%, and provision of concessionary flats in urban areas were also announced.

The way forward

There is a general perception among leading economists as well as the political leadership that the situation wouldn’t have taken a turn for the worse had the nation approached the international lending body earlier, even as little as six months. Responding to a request from the Prime Minister, the IMF has decided to send a staff level delegation to Colombo in the coming weeks to have further discussions over a bailout package. While there are hopes about the package stabilising the country in the short run, concerns from some quarters about the fallout of the austerity measures and their disproportionate impact on the marginalised populations are not without weight. The government will have its hands full in ensuring that the measures are temporary, with adequate care taken in implementing them.

The plans to redefine the powers of the Parliament also hit a roadblock when members of the ruling SLPP rejected the passage of the 21st amendment, seeing it as a political manoeuvre by the PM to expand his powers while deflecting the attention from the immediate economic crisis, deferring its discussion in parliament by a week. With friction between the opposition and the government and a dissonance between the demands of the civil society and the leaders, the coming months will be crucial for the country’s long-term economic health. The government will have to work towards pacifying the concerns of all parties and strive to form an interim government, inclusive of all political groups at the earliest.

For the Rajapaksa family, abdicating power and supporting a fresh start in the country would mean making themselves more vulnerable against the human rights and corruption charges against them, as well as destroying any chance of their return to power in the future. While the resignation of Basil Rajapaksa, ex-Finance Minister, does signal an end to the family’s domination, the possibility of the President stepping down still seems unlikely. Regardless, while the leaders scramble for power, it is the people who are caught in a quagmire of deprivation and political stagnation. The enormous humanitarian ramifications of the crisis and the obfuscation of the right of the people to a decent living standard hasn’t received the attention that is warranted. It is to be seen what the coming months will bring for the country, and whether the people’s demands for an accountable government is heard by the leaders in Colombo.