2024 Overlooked Risk: Digital Service Taxes and International Frameworks a Viable Solution for Expanding the Tax Base?

As the world economy is becoming more digitized, the tax system is facing a growing challenge, but not every country and business has been aware of the curse. Traditional rules governing taxation are only applied to businesses with a physical existence in an economic territory, so digital goods and services which may not have a tangible presence are not necessarily being taxed. This creates a controversy over whether the digital sector is paying a fair share of taxes. Meanwhile, as more economic activities are moving online, the economic importance of the online sphere has grown relative to that of the physical world. Therefore, the current legal loopholes in the tax system have increased states’ vulnerability to tax base erosion, which poses a latent threat to their long-term fiscal stability.

The digitalization of business models points to a need for a new type of tax in response to the unstoppable trend of digitalization. Some countries like the UK and Turkey have embraced the option called digital services tax (DST), which refers to taxes on gross revenue derived from a variety of digital services.

While DST can certainly widen the tax base by covering digital commodities that have been ignored by traditional taxes, the introduction of DST can hardly avoid problems. The online world is ultimately a virtual sphere with no clear geographical boundaries, so traditional tax concept jurisdictions of tax revenue may not apply to the digital sphere. Customers from a state with DST may be consuming virtual goods and services provided by companies outside the state. Alternatively, the companies may be collecting data from consumers from other countries to generate profits. Under imperfect information, these companies, despite offering products to foreign customers, may not necessarily be aware that they could be subject to taxation of another state. Such information and compliance issues can put them vulnerable to additional penalties, thus arousing controversies over the jurisdiction of tax revenue.

In light of the escalating threat of such risks and the uncertainty over the fiscal space, this report aims to explain how the digitalization of the world economy will impact the fiscal stability of both developed and developing countries in the foreseeable future. It also provides several recommendations for both the governments and the market to navigate the risk and prepare for what lies ahead.

In addition to the DSTs in the U.K. and Türkiye, there are other multilateral initiatives which set out to broaden the digital tax base and ensure fair tax is paid by multinational enterprises (MNE).One such initiative, and perhaps one of the most influential of its kind, is the OECD’s Inclusive Framework on Base Erosion and Profit Sharing (IFBEPS). The IFBEPS comprises of two pillars; (i) giving taxing rights to jurisdictions where MNEs conduct business even if MNEs do not have a physical presence in that jurisdiction, and (ii) ensuring that MNEs with over EUR 750mn in revenue pay a minimum tax rate in the jurisdictions where they operate physically even if they do not have business within that jurisdiction. The IFBEPS is due to come into effect across the 137 member countries at some stage later this year.

Although the IFBEPS is in so many ways a crucial initiative to tackle digital tax avoidance, it has two limitations. The first is that the vast majority of member countries are Western democracies, barring some exceptions in Africa and Asia. The second is that the IFBEPS does very little to actually boost bottom-up issues in the digital economy, namely participation. Nevertheless, both of these limits sit largely outside of the IFBEPS’ remit, though both are pertinent observations. For one, it remains to be seen if the adoption of IFBEPS pillars might push MNEs to operate in states that are not signatories to the IFBEPS to limit tax burden although at a potential risk of a reduction in human capital or moving costs. Secondly, a lack of bottom-up approaches means that whilst large multinationals would have more tax exposure plenty of small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) may not be impacted as significantly, especially in jurisdictions with large informal economies or tax delinquency rates. For those countries - with large informal economies and tax delinquency - IFBEPS might only increase overall tax revenues marginally without robust bottom-up approaches.

Fortunately there are examples of how such countries can go about increasing bottom-up participation. One such example is South Korea’s ‘Coin-Less’ society which aims to increase card payments and usage. The premise of the programme launched by the Bank of Korea (BoK) is to return change to cash-paying customers to prepaid debit cards through arrangements made between businesses, POS providers and debit card issuers. The logic of the programme is thus to highlight the convenience of card payments with respect to cash.

Figure 1: Bank of Korea ‘Coin-Less’ Scheme, taken from World Cash Report

Of course, a limitation to the implementation of such schemes is that they would probably only be implemented on a voluntary basis. Nevertheless, they could go a long way in promoting digital payments in the long-run in tax jurisdictions with low consumer digital payment usage and informal economies.

Nevertheless, DSTs and the IFBEPS mark a good first step in expanding the tax base to cover digital services but also have the potential to be the foundation for policies similar to the BoK’s ‘Coin-Less’ scheme, which could go a long way in combatting the informal economy by increasing participation in the digital economy. For this reason, the roll-out of the IFBEPS in 2024 will be crucial for expanding global tax bases into the digital space.

The Impact of the Israeli-Gaza Conflict on the Global Semiconductor Supply Chain

Overview of Israel's Semiconductor Industry

Israel boasts over 30,000 chip engineers and nearly 200 semiconductor companies, representing approximately 8 per-cent of the world's chip design talent and research and development firms. This unique concentration makes the region highly sensitive to conflicts affecting the semiconductor industry.

As of 2018, Israel had 163 chip companies and 35 research centres. By the first half of 2021, 37 multinational companies had established semiconductor branches in Israel. As of 2022, there are over 600 semiconductor companies, with nearly 200 specializing in chip design and development. Leading technology giants with significant operations in Israel include Intel, which has been prominent since establishing an overseas base in Haifa in 1974, as well as NVIDIA, Qualcomm, Cisco, Apple, Amazon, and Microsoft, all having significant chip design centres in the country.

Impact of the Israeli-Gaza Conflict on the Semiconductor Industry

Violent events in Gaza resulted in the abduction of engineers and the conscription of employees into the military. Intel, with approximately 12,800 employees in five major locations in Israel, faced challenges as one of its chip production facilities in Givat Shmuel is located southwest of Jerusalem, just 30 minutes from the Gaza border. The conflict also led to the kidnapping of NVIDIA engineer Avinatan Or by Hamas militants. Additionally, many companies reported that their employees were being massively conscripted into the reserves, causing disruptions in the workplace. In addition to this, the Israeli Defense Forces' blockade on Gaza effectively closed all crossing points, preventing thousands of Palestinians from crossing the border for essential services, including transportation, logistics, manufacturing, food, cleaning, and healthcare. This resulted in a lack of personnel needed for the operation of most industries.

Transportation disruptions, including flight cancellations and maritime route blockades, had profound effects on the supply chain. Many airlines suspended flights to and from Israel, causing passengers to be left stranded and impacting cargo transportation. The maritime industry faced additional challenges with the Israeli navy controlling traffic around major ports. Per recent updates from maritime insurance leader North Standard, Ashkelon Port, a key hub for oil tankers in Israel, is now inactive. Simultaneously, Ashdod Port is under an "emergency state." The Israeli navy has assumed control over the maritime traffic in and around the two major ports, exerting authority over the adjacent areas. This situation further complicates the maritime operations and poses challenges to the transportation of goods and resources in and out of the country.

Impact on Major Chip Markets

Israel's semiconductor industry is predominantly focused on design, boasting approximately 8 per cent of the world's chip design talent and R&D companies. The industry comprises fabless chip design firms, multinational research centres, semiconductor equipment enterprises, and a limited number of wafer fabrication plants.

Israel holds a significant position in various chip markets, including the United States, China, and the European Union. During the escalation of tensions between the U.S. and China in 2018, Israel witnessed an 80% surge in semiconductor exports to China. Semiconductors rapidly became a vital component of the economic relationship between China and Israel. Recent data indicates that, as of 2021, China remains Israel's largest export destination for chips. In the 12 months leading up to July 31, 2023, Israeli suppliers accounted for 14% of the EU's imports of computer processors. These imports primarily flowed through manufacturing facilities (fabs) owned by Intel and Tower Semiconductor Ltd., heading to Ireland.

Israel ranked second globally in the number of semiconductor startups in 2020, following the United States. These startups play a crucial role in technological innovation. However, their vulnerability is heightened during the current conflict due to a lack of funding and manpower. Looking ahead, the global semiconductor supply chain, which has just recovered from the impacts of the pandemic, may face further disruptions and damage in the long term.

Regional Inequality in the EU: A Risk to Enlargement?

The European Union’s enlargement policy “aims to unite European countries in a common political and economic project”. According to the European Parliament, enlargement “has proved to be one of the most successful tools in promoting political, economic, and social reforms”. Indeed, this is largely true: EU citizens are able to move freely for business, education, and leisure within the bloc; the EU has a robust uniform trade strategy, and above all, the EU has largely consolidated peace in Europe since its inception.

However, according to Emil Boc, the EU’s free movement policy suffers from a serious macroeconomic limitation: brain drain. The former Romanian prime minister – now mayor of Cluj-Napoca – has been actively raising awareness of this issue. Emil Boc recognises the issue is at the intersection of regional integration and national-level macroeconomic conditions. Simply put, the fundamental right to freedom of movement within the EU and adverse macroeconomic conditions in various Member States lead to talent from those Member States leaving to wealthier Member States or indeed leaving the EU altogether. A 2018 report by the European Committee of the Regions shows that the vast majority of ‘sending regions’ can be found in Southern Europe and in Eastern Europe, whereas ‘receiving regions’ were largely concentrated in Northern Europe and most of Italy. This iterates the systemic nature of the problem within the EU. Although there is yet no formal policy dedicated to addressing brain drain within the EU, the issue has gained salience over the last few years. Emil Boc was the Rapporteur for an official opinion published by the European Committee of the Regions, calling for a local government approach to tackle the issue. Similarly, over the last year, the European Commission has formally recognised the issue.

An intra-European brain drain may not seem at prima facie as a policy issue that ought to be addressed at the European level, it must definitely is. The reasoning is two-fold: firstly, brain drain means that periphery countries and ‘sending’ regions do not grow at the same pace as wealthier countries or regions which can drive euroscepticism. Secondly, for prospective countries looking to join the EU, the prospect of having talented members of the workforce emigrate might hamper enlargement.

Perhaps the second risk is more hypothetical than the first, the link between poor macroeconomic conditions (i.e. push factors for talented workers) and anti-EU sentiment and poor integration is well-documented in ‘sending’ regions and countries. Indeed, it is not a coincidence that Hungarians, Italians, Poles, and Slovaks have all elected outspoken Euroskeptics as head of government – for a long time those countries faced stagnating economic conditions and brain drain – now their governments are willing to challenge Brussels on core elements of foreign and internal policies.

Professor Sunak’s Education Policy: Legitimate Reform or ‘Weak’ Intervention?

On July 17 2023, Prime Minister Rishi Sunak unveiled plans to limit students enrolling to so-called ‘rip-off’ university degrees. He justified this policy position on the basis that 30 per-cent of university graduates in the U.K. did not find high-skilled employment nor did they enter further study. Perhaps more worrying, as the Prime Minister explained, a fifth of all university graduates in the U.K. would be financially better off not having gone to university.

This latter point is particularly accentuated by the relatively high cost of education at public universities in the United Kingdom with respect to the rest of Europe. But, even in a hypothetical scenario where the most part of tuition costs were absorbed by taxpayers, this would not change the first point of concern: that British universities are not sufficiently training students to enter the high-skilled workforce (which, according to government guidelines, can be many types of work).

Justification and Opposition

Arguably, upskilling students to enter the workforce is the primary telos of higher education institutions. Therefore, if those institutions are failing to perform that function effectively whilst indebting young adults and diverting tax revenues to inefficient institutions, it might be that case to increase the standard of students entering higher education by increasing the skills young people acquire in their formative years, as well as diversifying the post-16 pathways for those students who might not go to university should Sunak’s proposal come to fruition. Indeed, this is what much of what Sunak’s recent career as a politician has been dedicated to: as Chancellor of the Exchequer, he approved £1.6bn funding for T-level qualifications and since taking office, his government has announced a clamp down on “anti-maths” culture by extending compulsory mathematics in post-16 secondary education. However, with regards to the ‘rip-off’ degree crack down, there are still a lot of things which have yet to be defined. Specifically, the criterion for a ‘rip-off’ degree and how would those criterion be reviewed in a way that reflects the future of the labour market, rather than the past and present.

For example, if we consider a BSc in XYZ that today has very little employment prospects, but in 5 years’ time, that degree has significantly better labour market performance for graduates – how would British universities by able to catch up with international institutions that might have greater expertise in that specific field? There is also the question of discriminating against specific subjects or disciplines – namely humanities or social science. It is perfectly justifiable to intervene to increase the quality of higher education, but perhaps an alternative approach could be to place a requirement for university departments to have teaching staff with more technical diversity to avoid academic and pedogeological groupthink.

An Ulterior Motive for Reform?

Although a lot of administrative questions remain to be answered in the coming months, the crack down on ‘rip-off’ degrees could remedy a slightly different malaise. That is: declining pension replacement rates and increasing youth unemployment. In 2020, pension replacement rates were around the 58 per-cent mark, making U.K. pension payouts among the 12th lowest in the OECD. Effectively, pensioners on the State Pension lose nearly half of their contributions when they reach qualifying age. As stated by the Office for National Statistics, “[pension] payments by the government for unfunded pensions are financed on an ongoing basis from National Insurance contributions and general taxation”.

So, if the young people entering the workforce decreases (and if a fifth of those young people enter the workforce with substantial debt) at a faster rate than people reaching pension age, the overall pool for unfunded pensions will be proportionally smaller for each individual pensioner. Indeed, in 1990 just under two-thirds of people aged 15-to-24-year-olds were in some form of employment. That number is now around the 50 per-cent mark, which is still better than the average employment rate for that age group in the G7, OECD, and European Union, but the 50 per-cent figure is substantially lower than countries like the Netherlands where three-quarters of 15-to-24-year-olds are employed in some way. Furthermore, Table 1 shows that the proportion of people of working age will decrease slightly with respect to the dependent population between now and 2050.

Table 1 - U.K. Population by Age Group. 2023 data available here, 2050 data available here.

This is a demographic challenge that the UK, as well as the rest of Western Europe, will be contending with more and more as the years go by. Further, the aging population problem will require some sort of unpopular policy reform to European welfare states. As Macron has learnt in France, even something as simple as raising the retirement age can send a leading economy into calamity. In the U.K., the State Pension age has already risen to 67 for both men and women. A further increase to 68 may be on the cards, but Rishi Sunak’s education policies suggest the British government is trying to ameliorate the problem by increasing the employment prospects of the youngest earners rather than narrowly focusing on improving the fiscal efficiency of British universities.

Summary and Outlook

A lot of the practicalities of Rishi Sunak’s push to crack down on ‘rip-off’ degrees are yet to be seen. Concern and opposition are justified and necessary but claims that the proposal is an “attack on aspiration” are a bit far-fetched at the moment. Not least because the option of a decent State Pension is a public service worth protecting and maintaining, but substantially because little is known for the moment about this policy. Thus, until postulation becomes policy, criticisms are as constructive as they are speculative.

That said, Rishi Sunak’s push for education reform is warranted not just on pedagogical grounds but also for the sake of a crucial welfare service. However, the Conservative government must also avoid – by intent or miscalculation – to create elitist bifurcations between academic and technical qualifications.

The Unintended Consequences of Financial Institutions De-risking

In June 2014, the U.S. Treasury Department inflicted BNP Paribas with a $8.9 billion fine for failing to comply with U.S. economic sanctions against Sudan, Iran, and Cuba. This put the spotlight on the risks that the complicated web of international sanction regimes poses to financial actors. Indeed, in the last decade, the variety of contexts in which governments employ sanctions has grown, as part of a larger shift in the international arena towards the growing use of economic means to achieve foreign policy objectives. As a consequence, financial institutions have increasingly adopted a de-risking strategy to minimise the severe consequences of inadvertently violating sanctions, and sometimes over-complying with sanctions, and a priori refuse to enter into business relationships or terminate existing ones with entire categories of customers due to their alleged excessive sanction-related risks.

The result is the complete severance of financial transactions to and from sanctioned countries, even when they are authorised by humanitarian exemptions or are excluded from the sanctions’ scope. A 2017 survey by the Charity and Security Network of 8,500 U.S. humanitarian actors found that two-thirds of them had increasing financial access difficulties, while a 2015 World Bank report highlighted that 75 per-cent of the large international banks had decreased the number of their correspondent bank relationships mainly in sanctioned countries. However, de-risking violates the principle of non-discrimination of access to basic financial services, which is the 20th European Pillar of Social Rights. Also, it causes negative economic consequences on the populations in sanctioned nations and an increase in opaque alternative financial mechanisms that boost the underground economy and foster corruption and criminal activities. Thus, de-risking strategies jeopardise the effectiveness of sanctions as well as lead to outcomes that hinder Anti-Money Laundering and Countering the Financing of Terrorism (AML/CFT) efforts.

Drivers of de-risking

The main driver of de-risking is that sanction-related risks exceed financial actors’ risk appetite. In particular, sanctions give rise to (1) compliance risks, which are the risks of incurring fines and reputational losses due to the failure to comply with sanction packages, and (2) regulatory risks, i.e., the risk that a future change in sanction laws will negatively affect financial institutions’ operations. Indeed, the lack of uniformity and clarity of multiple overlapping sanction regimes and the complex company hierarchies put in place by sanctioned individuals to circumvent asset freezes against them make it challenging for financial actors to comply with different countries’ sanction regulations and understand which entities fall within the scope of the different sanction packages. Moreover, the growth of sanction lists means that financial institutions also have to foresee future developments in sanctions, since, as a senior banker at a large Asian bank put it, “no one would like to sign a billion-dollar trade finance deal only to be told a week later that the entity has been added to the sanctions list”. This uncertainty couples with the US’ enactment of secondary sanctions and the fact that sanction violations are strict liability offences, which means that anyone violating sanctions even involuntarily commits a criminal offence thus triggering hefty fines -as in the case of BNP Paribas- or the loss of access to the US financial system and the USD. The result is that deciding which transactions from sanctioned countries are legitimate carries too big risks for financial institutions. The only measure to mitigate such risk would be to carry out enhanced due diligence to verify customers’ (individuals, firms, but also respondent banks) identity, as well as the nature and purpose of their activities. However, this would be considerably costly and time-consuming, and would hinder banks’ profitability. In such a situation, de-risking becomes the natural preferred choice for a rational economic actor.

Consequences of de-risking

De-risking by financial institutions has a dual negative impact:

1) Negative impact on correspondent banking relationships (CBRs). CBRs are financial relationships aimed at executing cross-border payments between two banks (respondent banks) that do not hold accounts with each other and thus use a third institution (the correspondent bank which usually is a US or European international bank) to act as an intermediary. However, correspondent banks need to be certain that they are not executing transactions involving sanctioned individuals or goods in order not to incur the liabilities and sanction-related risks analysed above. For this reason, they are increasingly breaking ties with respondent banks operating in sanctioned (and thus high-risk) countries. According to the Bank for International Settlements, from 2011 to 2019 the number of CBRs globally decreased by 22 per-cent, and more than 50 per-cent in sanctioned countries [Figure 1 below]. This exclusion of sanctioned countries from the financial payment system has a negative consequence on (1) cross-border trade and (2) remittance flows, since local banks and money transfer operators cannot process international payments and provide basic trade finance services like import or standby letters of credit. Lastly, the lower access to the USD leads to a fall in tourism flows and FDI into sanctioned countries.

Figure 1: Sanctioned Countries Are Increasingly Excluded From the finanical System

2) Negative impact on the ability of international humanitarian organisations to respond to crises in sanctioned countries. Often, US and European banks close NGOs’ accounts or refuse to execute financial transactions to fund humanitarian projects in sanctioned states, even when such transactions are expressly authorised by sanction regimes and NGOs are granted humanitarian exemption by governments. This is because these NGOs operate in areas deemed to be too high-risk, and banks are not familiar with humanitarian organisations’ business model, which makes it difficult to identify NGOs’ trustees, suppliers and beneficiaries. Banks do not provide any rationale or possibility of appealing their decisions. Even when transfers of humanitarian funds are eventually authorised, still they are delayed by an average of 4-6 months, which hinders the fast implementation of projects that is necessary to tackle humanitarian crises.

As a result, financial transactions to and from sanctioned countries are executed via alternative channels such as shadow banking or the physical transport of cash across borders. However, these are unregulated and not transparent substitutes, which makes it easier to circumvent AML/CFT regulations and carry out illicit transactions for criminal or corruption purposes.

Recommendations

The following measures can be taken to tackle de-risking by changing financial institutions’ cost-benefit analysis regarding over-compliance with sanctions:

1) Promoting the adoption of new digital technologies by the clients of financial institutions. This can facilitate banks’ due diligence, thus lowering their compliance costs and sanction-related risks. Private firms and NGOs operating in sanctioned countries can lower the probability of being de-risked by using a Legal Entity Identifier (LEI). This is a 20-character code developed by the International Organization for Standardization, that uniquely identifies legal entities and their true ownership structure. LEI records are publicly accessible, thereby making it easier for banks to verify their customers’ identities and ensure that they (or their owners) are not included in any sanction list. Similarly, respondent banks in sanctioned states can adopt Know-Your-Customer (KYC) Utilities, which are digital repositories containing information about banks’ customers. By allowing US and European correspondent banks to access their KYC utilities, local respondent banks can expedite due diligence procedures and increase their transparency, thus reducing sanction-related risks and the costs of CBRs.

2) Adopting measures by U.S. and European regulators to reduce the uncertainty surrounding sanction regimes and reassure banks that the due diligence they have in place is sufficient to prevent any involuntary violation of sanctions and their consequent fines. This can involve clarifying sanction requirements, issuing detailed guidance on how to manage high-risk scenarios arising from sanction regimes without withdrawing from sanctioned countries, as well as carrying out reviews of US and European financial institutions’ risk assessment/compliance procedures to test their adequacy. Already existing or ad-hoc multi-stakeholders dialogue forums could facilitate such exchanges between financial actors and authorities. At the same time, sanctioning countries could formalise the non-prosecution of sanction violations by financial institutions with strong sanction-compliance mechanisms, provided that this is done inadvertently and in good faith. This would guarantee that banks will not have to pay fines if the funds they transfer for humanitarian purposes to sanctioned countries accidentally end up in the hands of sanctioned individuals. Therefore, sanction-related risks for financial actors would be reduced.

3) Establishing channels through which banks’ de-risking decisions can be legally challenged and mandating financial institutions to notify financial regulators of the rationale to implement activities aimed at de-risking. In this regard, standard templates can be created requiring banks to specify which kind of sanction-related risks they face, the measures considered to mitigate them and the reasons why these measures are insufficient, thus making de-risking necessary. This would increase the scrutiny on banks’ de-risking decisions and reduce the a-priori de-risking of entire categories of customers based on their economic link with a high-risk country. Consequently, it would ensure that financial institutions employ individual risk assessment procedures that do not violate the principle of non-discrimination.

Conclusion

Even though economic sanctions are established by governments, they are concretely implemented by private actors like financial institutions. The current complex web of overlapping sanction regimes is such to tilt the decisions of rational private economic actors in favour of de-risking. This is what is happening in the case of Russia: although sanctions include exemptions that allow for payments of Russian energy, the sanction-related risks associated with potential breaches of sanction packages have sparked over-compliance from European financial institutions, with Société Générale, Deutsche Bank, BNP Paribas and HSBC even exiting the Russian market altogether. In this regard, the recommendations of this policy brief would allow to change financial institutions’ cost-benefit analysis, thus tackling de-risking and its negative consequences.

The Sino-US Technological War: A Shift in the Pattern of South Korea’s Trade

East Asian countries have always been tempted by the profitable market of China, but the importance of the Chinese economy to South Korea seems to be on a decline. According to the Bank of Korea, goods exported from South Korea to China decreased to $122 billion between 2021 and 2022 by 10 per-cent, while goods exported to the United States rose by over 22 per-cent to $139 billion. This marks the first time that the United States overtakes China as the biggest export market of South Korea in nearly 20 years. Such a shift in South Korea’s trade pattern can be ascribed to the economic competition between the eagle and the dragon in the advanced technology war. Their technological war has provided opportunities for South Korea to enhance its business relationships with the United States, while weakening the business prospect in China.

Technology is destined to be the driver of future economic growth. Leading powers have been developing high-tech industries like AI, robotics, biotechnology, and electronics to promote economic development and transformation. China and the United States are no exception. The competition between them is, in fact, particularly fierce because of the escalating tensions between them. To fully develop these high-tech industries and win the technological race, these states will need an essential material, semiconductors. South Korea is an important player in the global semiconductor and advanced chips supply chain. By December 2020, South Korea accounts for 37 per-cent of the production of semiconductor chips with a node size lower than 10 nm. Its two largest manufacturers, Samsung Electronics and SK Hynix, account for 17 per-cent of the global market share. In 2022, they account for about 50 per-cent of the global market share in NAND flash memory chips and almost 70 per-cent of that in the DRAM segment.

Given that the United States is eager to maintain its advantage in advanced technology development, expanding into the American market is appealing to South Korean manufacturers. The two countries have been each other’s most important allies in managing the stability of the East Asia and Indo-Pacific region. This provides a favorable circumstance for South Korean companies to build stronger trade relations with the United States. Meanwhile, Washington’s ambition to consolidate its leadership in the technological race will also boost the demand for South Korea’s semiconductor and chips, which helps contribute to a greater export of South Korea to the United States.

While South Korea is inclined to export more goods to the United States, the competition can drive China to import fewer goods from South Korea. Admittedly, the Chinese market is a major revenue source for South Korean high-tech giants. The business prospect in China, and Beijing’s eagerness to surpass the United States in the technological race, should drive South Korea to export more goods to China. However, the technology war has caught South Korean manufacturers in the middle between China and the United States. The United States is now implementing export control to suppress China’s access to sensitive technology. The CHIPS Act implemented by Washington does not allow subsidy applicants to engage in certain significant transactions involving expanding semiconductor manufacturing capacity. This limits the export of critical materials and technology from South Korea to China. Fearing the potential retaliation from the United States, South Korean manufacturers are incentivized to avoid over-expanding in the Chinese market and trading sensitive products.

Moreover, under the technological war, American suppression of China encourages the latter to be more self-reliant. Apart from imposing a series of sanctions on Beijing and limiting its access to critical materials, the US is also persuading or pressuring other countries, including South Korea, to side with Washington and not to collaborate with China to develop advanced technology. For example, the United States, South Korea, Japan, and Taiwan have formed the Chip 4 initiative to coordinate policies on supply chain production and research. This has forced China to sharpen its domestic manufacturing capabilities, so as to reduce reliance on foreign technology and promote the development of its own high-tech manufacturing sector. Accordingly, together with the Made in China 2025 strategy released in 2015, China has been making increasing investments to develop its semiconductor, AI, bio-medicine, and other advanced industries. All these could reduce demand for South Korea’s strategic or critical materials.

Ultimately, in the era of the fourth industrial revolution, technological competitions between the leading economic powers appear to be inevitable. As a technological powerhouse, South Korea is also dragged into the technological race and its trade with China and the United States will observe great changes. High-tech manufacturers and relevant industries will therefore have to navigate the changing trade dynamics, so as to prepare themselves to face a further escalation of Sino-US technological war in the future.

Football and Finance: The Unholy Alliance?

On June 10 2023, the culmination of over a decade of monumental growth resulted in Manchester City winning the treble: the FA Cup, the Premier League, and the Champions League. Not only is this a monumental feat for a club to achieve, but it also highlights the changing relationship between football and finance. Increasingly, football clubs are becoming a form of alternative investment for the ultrawealthy, but is this actually a new phenomenon? And with the stunning returns that Manchester City has given back to shareholders and fans alike, is there an easy recipe for success or are clubs (and private equity firms) trying to piggyback on City’s success heading for failure?

Success on the Field

The club was in a dire condition in 2008. After fluctuating between success and failure in the 1990s and early 2000s, there was hope in the form of ex-prime minister of Thailand Thaksin Shinawatra who bought the team in 2007. However, due to mounting legal issues, he was forced to sell the club to Sheikh Mansour, Deputy Prime Minister of the UAE, for $200 million. The second turn around for the club happened after Roberto Mancini was brought in as manager in 2009. A series of key signings directly led to one of the most iconic moments in Premier League history: Sergio Aguero’s last minute winner against Queens Park Rangers to clinch the Premier League title from rivals Manchester United’s hands. City’s first Premier League title in over forty years cemented the new winning mentality that Mansour had brought to the club, but his work was only getting started.

Success in the Boardroom

Ferran Soriano was appointed CEO of Manchester City in 2012 and he immediately began working on an idea he had had while working for Barcelona. He had envisioned a multi-club ownership business which would grow support abroad for City whilst allowing member teams to share medical and scouting data. As support grew from abroad so too would sponsorship, creating a steady cash flow for City. Though the idea is not entirely unique (look at Red Bull with its plethora of teams ranging across multiple sports) the City Football Group (CFG) created in 2013 is unmatched in its reach. Buying stakes in teams from nearly every continent, Soriano wanted it to revolutionise how football was enjoyed. Called Disneyfication, the idea reflects the holistic experience Disney creates by intersecting its many franchises and products. In the same way, CFG’s media arm and unique match-day experiences worked to intersect football with entertainment. At the same time as this, £150 million were spent on upgrading Manchester City’s facilities, to better train youth talent and attract the best coaches in the football world. Furthermore, in 2014 Manchester Life was launched by Mansour, an initiative to rejuvenate the rundown areas of Manchester by building affordable housing to later attract retail and leisure developments. Mansour had a clear aim: to attract the best players, coaches, investors, and sponsors in the world. With Amazon partnering with the club to produce a documentary series, legendary manager Pep Guardiola joining in 2016, and a star-studded squad feared across all leagues, it's safe to say they achieved their goal. But why has this not been replicated at other clubs?

State Sponsored, Sponsoring a State... Or both?

“Where some states have an army, the Prussian army has a state” – Voltaire

The famous saying was used to describe the reliance the Prussian state (now Germany) had on its army. The same accusations have been levelled against Manchester City as to how they became so successful so quickly, and as to why Mansour poured so much money into the club. With the club currently facing hundreds of allegations of breaking financial rules, it would be disingenuous to present their success, both as a club and an investment for Mansour, as purely due to good management and business decisions. Critics argue that City’s success would not have been possible without the artificial enhancing of revenues by the UAE. For years allegations have been levelled against City and CFG as a way for the UAE to “sportswash” their image, which refers to the using of sports by autocratic states to distract from their repressive policies. While allowing the state to diversify its economy away from oil, it also associates the UAE with the successes of Manchester City, distracting from the domestic policies of the state. But independent of this, there are still good practices other investors and teams wishing to emulate City’s success can copy.

Billionaire Investors, skip to this bit

What sets Mansour apart from other billionaire owners and the private equity (PE) firms that back them is that he was willing to take the back seat and effectively delegate to those who had much more experience than himself. More than decade on from buying City, Mansour has spent billions investing in the club. However, he has still seen an eye-watering 1,700 per-cent return on his investment since 2008, and this is discounting the billions raised by selling stakes to PE firms China Media Capital in 2018, and Silver Lake in 2019. Contrast this with the high-profile disagreements that plague clubs with similar financial backing, such as PSG (Paris Saint-Germain) and Chelsea FC, or the Glazer family funnelling billions out of Manchester United, and it is easy to see why Manchester City has been so successful. Why were the Venture Capital firms who backed Mark Zuckerberg before Facebook went public happy with receiving shares with no voting power? Because they were not only investing in Facebook, they were also investing in the genius behind it. Likewise, Mansour’s light hand has allowed the Spanish trio of Soriano, Guardiola, and director of football, Txiki Begiristain to implement their vision for success unimpaired. Whether or not they did this in accordance with financial fair play rules, is yet to be seen.

A Toxic Relationship

“They make a desert and call it peace” - Calgacus

When people speak of “alternative investments” in finance, they normally refer to commodities, art, or, recently, cryptocurrencies. Though PE is normally categorised with this class of assets, football clubs bought through funds raised by these firms are not usually seen as an investment class of their own. Understandably, many football fans would be furious to see their clubs be seen as such. Just like the criticism levelled against the Romans by Scottish Chieftain Calgacus, the ruthless profit hunting of PE firms is something football fans have watched in fear. Already notorious in the finance world, PE firms have begun to be seen as business vultures, coming into ailing firms and ripping them apart for profits before leaving a decade or so afterwards. The idea of football as a business is one European fans hate, but realistically business and football have already been inextricably linked for decades. The idea that money is ruining the beautiful game is romanticised, but fans readily turn a blind eye when the summer transfer window comes along, and the chequebooks are brought out. On the other hand, the working-class roots of football should not be forgotten in the pursuit of money.

While the CFG has led to fans across the world also getting to enjoy football, equally audacious plans like the European Super League are clear examples of finance trying to change the nature of football with no regards to the opinions of fans, who are ultimately the driving force behind the game. If a CEO were to act against the interests of their shareholders, they would be swiftly sacked. As the finance world takes more and more of an interest into football, it should not forget who the true shareholders of the game are: the fans.

The Future of Football

We likely won’t find out if Manchester City broke any rules in their road to success for another few years, and that’s ignoring the lengthy appeals process which they will pursue if found guilty. But the questions raised by the club will be debated for many years to come. How closely linked should the financial world and football be? How much scrutiny should investors face when buying clubs? Should politics play a part when assessing potential future owners for a club?

Nonetheless, investors hoping to emulate City’s success would do well following Mansour’s method. He could have easily culled much of his management after successive failures despite billions spent, but his patience has finally been rewarded. Critics would argue that it was not patience to win which kept from doing so, but that he was content that the club was playing some part in distracting from the policies of his nation. And here lies the question we will see answered sometime in the next decade: Where some countries have football clubs, does Manchester City have a country?

The ‘Biden-McCarthy Deal’: Is America’s Business Still… ‘Business’?

On June 3 2023 President Biden signed into law the ‘Biden-McCarthy Deal’, formally known as The Fiscal Responsibility Act (FRA; 2023) or H.R. 3746. The Act is the result of 6 months of debate in Congress and Congressional Committees, before Speaker of the House - Kevin McCarthy - and Joe Biden managed to strike a deal. Biden’s signature quelled his administration's second debt ceiling ‘crisis’, the first having occurred in late October 2021. The debate around the FRA highlights what is becoming a recurring theme in U.S. economic policy: ideological differences over non-economic policy leading to increasing economic policy uncertainty and ‘crisis’ events. For this reason, The FRA (2023) is being championed as a crucial moment for U.S. bipartisanship.

What the FRA Tells Us About Politics and the Economy

The FRA effectively suspended the debt ceiling until January 2025. Section 401(c)(1) gives the legal basis for much of already legally approved legislature and expenditure to be carried out, whilst Section 402(c)(2) prohibits The Secretary of the Treasury from issuing obligations until January 1 2025 “… for the purpose of increasing the cash balance above normal operating balances”. It is worth noting that The FRA is a long legal document, but Section 401 demonstrates the broad partisan compromises: the Biden administration and the Democrats can carry out their approved reforms and policies, and the Republicans got some of what they wanted in terms of limiting drastic money supply increases, quelling concerns of potential inflationary pressures arising from Biden’s policies.

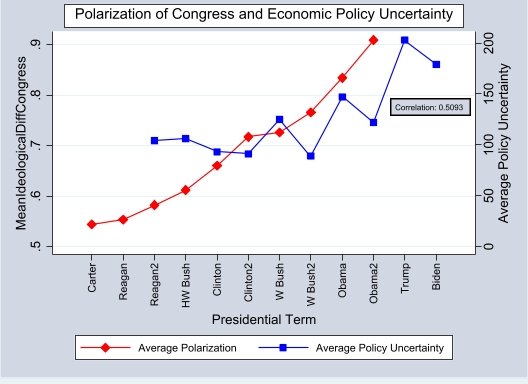

Rana Foroohar, Global Business Columnist and Associate Editor at the Financial Times, highlights that much of the debate around The FRA has been largely hung up “… on highly political issues such as defunding the Internal Revenue Service”. This draws attention to the fact that decades-long increases in political polarization is damaging the ability of the legislative branch to devise stable and predictable economic policies, which leads to recurring self-imposed debt ceiling ‘crises’ and government shutdowns that hamper investor confidence. Figure 1 visualises this increasing polarization and economic policy uncertainty:

Figure 1: Mean Ideological Difference (Polarization) of Congress and Average Economic Policy Uncertainty

The red curve uses data from Brookings to demonstrate the average ideological differences between both sides of the isle in Congress. The values used in Figure 1 were obtained by finding the difference in means of each legislature and plotting them against the corresponding term of the serving executive. Likewise the blue curve showing average economic policy uncertainty is a four-year average, corresponding to the four-year terms of the executives starting from the Carter administration. This data is obtained from Economic Policy Uncertainty (EPU) – a thinktank that specialises in political risk indices and indicators. The economic policy uncertainty index methodology comprises three components: automated analyses of media reports, the Congressional Budget Office’s publication of expiring tax code provisions, and expert sentiment around inflation and government purchases.

Of course, the data are descriptive and the positive correlation – 0.5903 – is not in and of itself indicative of any evident causal effect. Nor is data available for every administration. However, the challenges of recovering financially from COVID-19 and heightened political tensions at the qualitative level are a worrying sign that polarization is permeating economic policymaking. January sixth-esque events are not common occurrences in American history, and even shutdowns and risks of default have only become commonplace since the late 1970s. So if in 1925 the “chief business of the American people [was] business” then in 2025 the chief business of the American people will be politics.

Outlook for 2024: Yet Another Consequential Election

With the next potential debt ceiling ‘crisis’ set to come about in 2025, the eventual winner taking office after the presidential election in 2024 will have little time to get to work. Amid the ever-growing list of Republican candidates, former president Donald Trump and the Governor of Florida Ron DeSantis appear to be front-runners in the race. Asa Hutchinson is the next high-profile GOP candidate. On the other side of the aisle the incumbent Biden and Robert F. Kennedy, alongside Marianne Williamson.

At this stage it is still unclear what any of these candidates’ policies might look like considering there is still time to go until campaigning officially starts and intra-party housekeeping finishes. Of the candidates, the two most recent presidents do not have much to boast about economically. On the one hand, Trump inherited an economy at the apex of a growth trajectory and benefitted substantially from that fact prior to the pandemic. On the other hand, Biden inherited an economy with a post-COVID hangover and a war in Europe. Crucially, Biden is also having to contend with his counterpart in Beijing pursuing expansive foreign policies, flirting with de-dollarization.

Certainly, whoever is in office by February 2025 will have to navigate a turbulent macroeconomic environment domestically and internationally – as will transnational corporations and investors. “Political risk”, for corporates and investors, is becoming less of a concept attached to far-flung economies and is increasingly becoming a concept attached to what were once ‘stable’ economies in the West. The businesses who can best anticipate this will be the ones to best adapt to the global macroeconomic environment in the not-so-distant future.

The Rise of Nvidia: California’s Second Gold Rush

It all begins with an idea.

During a gold rush, sell shovels. Nvidia's success has been likened to the gold rush era, where those who sold the essential tools profited immensely. In this AI gold rush, Nvidia is selling the crucial components required for AI applications. The market for AI chips could reach $60 billion by 2027, with Nvidia already dominating 75 per-cent of the market. The latest H100 processors, optimised for AI architecture, are currently selling at around $40,000 on eBay, further emphasising the market's demand for these cutting-edge chips.

Nvidia, a periphery player in the field of artificial intelligence (AI), has issued a remarkable revenue forecast that far exceeded Wall Street's expectations. While analysts had expected revenues to be $7.2 billion, Nvidia announced a revised forecast of $11 billion bolstered by the rising wave of generative AI systems like ChatGPT. The company has experienced a substantial increase of 27 per-cent in its stock value and is witnessing an unprecedented demand for its products. As a result, Nvidia's total market capitalization has soared to a staggering $960 billion, firmly placing it as one of the most valuable companies in the world just behind the likes of Google, Apple, Saudi Aramco, and Microsoft. On May 30 2023, Nvidia’s market cap hit the $1 trillion mark.

The influence of AI is expanding beyond the tech sector, with financial institutions also embracing its capabilities. JP Morgan, for instance, is developing a ChatGPT-like service that utilises AI to select investments for customers. The company has recently applied for a trademark called IndexGPT, following in the footsteps of other banks like Goldman Sachs and Morgan Stanley, which have been testing AI for internal use. Nvidia's innovative technologies and strategic foresight ensure its pivotal role in revolutionising various industries and pushing the boundaries of artificial intelligence.

To meet the overwhelming demand for its products, Nvidia is significantly increasing its supply. CEO Jen-Hsun Huang has acknowledged the concerns of consumers regarding shortages of Nvidia H100 chips, which are crucial for AI applications. This is due to many of Nvidia's main customers, including consumer internet firms, cloud computing providers, and enterprise clients, rushing to apply generative AI technology to enhance their businesses. While Nvidia's graphics cards were initially targeted at graphics-heavy video games, the company has successfully diversified its consumer base. The launch of generative AI systems like ChatGPT in November has sparked an AI arms race, prompting various industries to adopt these technologies. The widespread adoption has fuelled Nvidia's sales growth and propelled its stock price to achieve the largest one-day increase in a company's value ever recorded.

Nvidia's position in the AI market is solidified by its continuous technological advancements. With the most advanced GPU, networking capabilities, and embedded advanced memory, the company offers a comprehensive solution to fuel any firm’s AI ambitions. Its management team’s foresight has placed Nvidia years ahead of its competition, Intel and AMD. While CPUs developed primarily by Intel and AMD lack the processing power required for AI, Nvidia's GPUs provide the necessary horsepower for AI computing. Nvidia's remarkable revenue forecast and subsequent stock surge signify the company's dominance in the AI market. By capitalising on the growing demand for generative AI systems, Nvidia has positioned itself as a frontrunner, leaving its main competitors behind. As AI continues to shape the future of computing, Nvidia's innovative technologies and strategic foresight ensure its pivotal role in revolutionising various industries and pushing the boundaries of artificial intelligence.