Soft connectivity as soft power: digitalisation, interoperability, and the Middle Corridor

Executive Summary

Effective soft connectivity is crucial to the operation of a system as complex, and with as many moving parts, as the Middle Corridor. Implementing this requires adept project management, a service grounded in knowledge and experience that the EU is well-equipped to offer.

Smart investment in this sector can help mitigate certain challenges associated with infrastructure development in the region to make the kind of sustainable, stabilising, mutually beneficial change integral to the Global Gateway initiative.

The ramifications of EU involvement in this aspect of the route’s development will play an important role in navigating the territory between soft power and sustainable development, and, if conducted well, could provide a solid foundation for future EU-Central Asia relations.

In January 2024, the European Union (EU) made a €10 billion commitment at the ‘Global Gateway Investors Forum for EU-Central Asia Transport Connectivity’. This pledge – an extension of its Global Gateway initiative which aims to stimulate smart, clean, and secure digital, energy and transport connections, and strengthen health, education and research systems worldwide – seeks to support the development of connectivity infrastructure in Central Asia through the expansion of the Middle Corridor; also known as the Trans-Caspian International Transport Route (TITR).

A crucial part of the forum, and an immediate area of concern for the project as a whole, was the necessity to have in place efficient soft connectivity infrastructure to support the corridor’s overall momentum – a point of particular importance in view of the role Kazakhstan will play as the route’s conduit to the Caucasus and point of contact with the rest of Central Asia. As such, the Kazakh government is seeking to engage the services of project-management consultancies to manage various aspects of this system. In particular, it is looking to draw on the knowledge and experience of EU businesses, and experience the benefits of deepening ties to its largest trading partner.

With the EU looking to further its strategic autonomy, and Kazakhstan eager to diversify its economic relationships, smart investment partnerships are fertile ground for mutually beneficial development. As an integral part of the route’s operation as yet unburdened by long-standing claims, and a resource invaluable to the dispersal of benefits throughout the region, investment in soft connectivity is a powerful alternative path towards long-term economic symbiosis. Being on the cusp of great change, not only due to the accelerated timeline of geopolitical tensions over the past five years, but also because of the Artificial Intelligence (AI) revolution already underway, has created a window of opportunity in this sector: the Global Gateway’s investment strategy should recognise this, and fast.

What is Soft Connectivity, Why is it Important, and What is Needed?

Soft Connectivity and the Global Gateway Mission

Soft connectivity is a term given to the systems which sustain physical infrastructure projects. From policy coordination to digital communications, to the development of harmonious business relationships, it is a fluid support that encompasses the visible infrastructure of economic corridors. As such, it is an essential concern of the Global Gateway, whose interest in the security of global supply chains is tied to long-term sustainable development. Considering the scale of the TITR project and the complexity of trying to accommodate the myriad of governments, industries, businesses, and workforces involved, logistical modernisation and the implementation of a cohesive communications system will be crucial to making the corridor operational, sustainable, and accountable.

This support will be fundamental to fulfilling the Global Gateway’s design of public and private investment to create links, not dependencies – a solution marketed as an alternative to the potential entrapments of China’s Belt and Road Initiative. With soft connectivity’s propensity for decentralisation in mind, Miroslav Dusek from the World Economic Forum has stressed the importance of achieving an economy of scale for Kazakhstan and its adjacent countries: crucially, the route must be as much a market as a corridor.

Digitalisation, Interoperability, and PPP

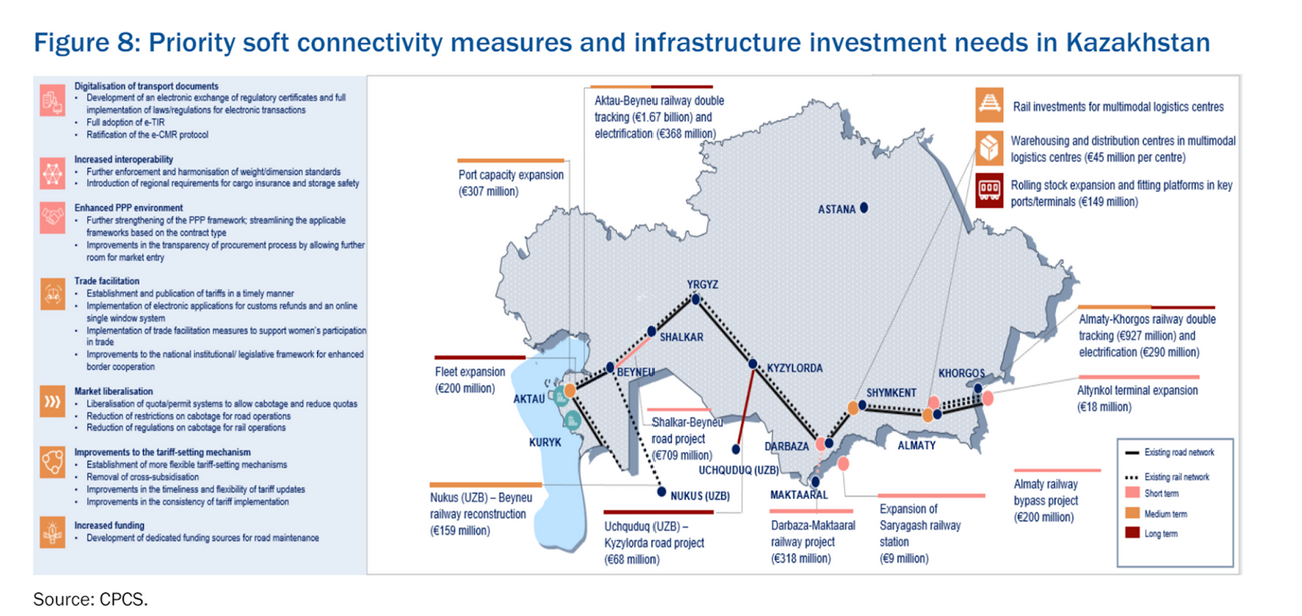

The findings from the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD)’s 2023 report on sustainable transport connections between Europe and Central Asia highlight seven key areas of soft investment: digitalisation, interoperability, improving the public-private partnership (PPP) environment, trade facilitation, market liberalisation, bettering tariff-setting mechanisms, and increasing funding allocations for asset maintenance.

Source: Sustainable transport connections between Europe and Central Asia, European Bank for Reconstruction and Development

The most immediate areas of concern, digitalisation, interoperability, and PPP, are thoroughly interlinked and, because of the transnationality of the procurement process, must be brought about in tandem. The array of PPP procurement contracts awarded in Kazakhstan surrounding the Middle Corridor project (ranging from insurance and securities contracts with the Asian Development Bank (ADB) to education and training from the United States Agency for International Development (USAID)), means that creating an interoperable, multi-modular platform through which a common data environment can be accessed is vital. This general need for integrated information and communication technologies (ICTs) requires mass digitalisation: an international mosaic of interdependent public and private sector bodies must be able to communicate in order to manage supply and capital effectively and transparently. With this in mind, it is significant that Kazakhstan received its first influx of Starlink equipment in February 2024, a technological update which will help to facilitate the internet-dependent digitalisation process across the route, much of which passes through rural and remote geographies whose access is unreliable.

Digitalisation is needed not only to cater to certain flashpoints along the route (for instance ports and border crossings), but in order to establish a system of communications between separate elements of the process, connecting a variety of different organisations, from a multitude of different investing nations. Along Kazakhstan’s border with China, for instance, Singaporean company PSA International launched ‘Tez Customs’ in 2023 – an automated, paperless customs clearance initiative designed to increase transparency and expedite bureaucratic bottlenecks – which has already begun streamlining transportation flows across the border. This process was especially crucial to easing the congestive teething issues of 2022 which saw the route receive a sudden influx of containers as a result of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. At the other end of the country, procurement contracts are actively being advertised to EU consultancies. Speaking at the Global Gateway Investors Forum in 2024, Kazakhstan’s Transport Minister, Marat Karabayev, offered management of its Caspian Sea ports and 22 airports to EU investors. Again, as a result of new interest in the route since Russia’s increased aggressive stance towards the West, maritime traffic through the ports of Aktau and Kuryk increased by 86% from 2022 to 2023 and will continue to rise in the years to come, requiring complex physical infrastructure changes such as dredging the Caspian Sea. To cope with this kind of rapid increase and its consequences, efficient project management strategies, such as the digitalisation of transport documents, are needed immediately.

The AI Trade Revolution

The impact of AI on global trade cannot be underestimated, and it will be instrumental in the development of the TITR. The Dubai Multi Commodities Centre (DMCC)’s 2024 report on the future of global trade has predicted that the integration of machine learning and automation technologies into commerce will add $15 trillion to the world economy by 2030. While the ramifications of this technological revolution are extensive across the Middle Corridor as a whole, from the accelerating effect of cryptocurrencies and blockchain technologies in transnational commerce to cross-border data flows and tensions over semiconductor production, within Kazakhstan, they are especially pertinent to the managerial efficiencies of soft connectivity measures discussed above. The need for digitalisation and interoperability – the ICTs and multi-modular operating systems – will in large part be dealt with by consultancies utilising AI’s ability to reduce language barriers, facilitate customs processes, shrink overheads, and optimise supply chains. Tuas Port in Singapore (run by the same PSA International of ‘Tez Customs’), for instance, is on track to become the largest fully automated port in the world – a successful example of complete and efficient AI integration towards which Kazakhstan’s Aktau and Kuryk are surely looking. As a result of AI integration increasing across the board, digital trade agreements attempting to regulate intellectual property protections, supply chain management, and the free flow of data, will underpin much of soft connectivity’s legislative backdrop.

Panels and the Public Sector Presence

Despite its digital footprint, it is human relationships which underpin successful soft connectivity investment. Here, the EU has laid the groundwork for future success: in fostering amicable business relationships since its pivotal Enhanced Partnership and Cooperation Agreement (EPCA) with Kazakhstan in 2015, the EU has created an investment environment of economic collaboration. This emphasis on partnership is crucial to dealing with the complexities of soft connectivity investment, many aspects of which encourage both private-sector innovation and public-sector regulation.

The agreements made at the Global Gateway Investors Forum saw this synergy in action, and the panel discussion on ‘Making the Corridor Work: Interoperability and Harmonisation for Connectivity’, helped in the confirmation of a Coordination Platform and a Regional Prosperity-focused Programme designed to monitor progress across the corridor and emphasise development beyond its immediate vicinity. In addition, the ‘Resident Twinning Advisors’ instrument will see EU advisors placed within the Ministries of Transport of all five Central Asian countries from 2024: the groundwork for the EU becoming an integral part of Kazakhstan’s digital transformation is already laid.

Diplomacy and the Paths Ahead

Challenges to Sustained Investment

At a time when access to critical raw materials is becoming a defining feature of global power, good diplomatic relations with Kazakhstan and the surrounding Central Asian countries have never been more important. As such, the EU faces difficult questions as to how to conduct its investment presence over time. Far from alone in its interest in the region, and a new arrival compared to Russia and China, there is a real need for the EU to secure its place within a competitive market.

This environment of global competition is accompanied by rising protectionist attitudes within Kazakhstan. Investment agreements abound with clauses to protect the transfer of operations in key sectors from green energy to critical raw materials mining. For instance, in the green hydrogen production project set to be launched by Hydrasia Energy (part of German-Swedish company Svevind) in Kazakhstan’s Mangystau region overseen, 90% of all employees must be Kazakh citizens. While Ainur Tumysheva, director of investments at Hyrasia Energy, acknowledges that “100% localization is challenging due to the industry’s novelty. Technology and knowledge transfer from foreign specialists will be necessary”, there seems to be a concerted effort to create a roadmap away from needing overseas expertise. This effort is supported by the country’s EU partners: given German Federal President Frank-Walter Steinmeier’s active endorsement of the Kazakh-German Institute of Sustainable Engineering Sciences where young Kazakh citizens are trained by German practices in sustainable engineering for the technologies of tomorrow, it seems eventual Kazakh autonomy is the goal – albeit with a German legacy.

Central Asian countries have also made clear their aspiration for greater manufacturing autonomy over the energy sourced and materials mined within their borders, an eventuality which would stimulate domestic development, bolster transregional commerce, and shape the corridor to be for trade as well as transit. Across the TITR, hard connectivity and physical zones of investment are rapidly shoring up their defences with an eye to future demand, making their investment environments appear short-term.

Smart Investment Solutions

For the Global Gateway initiative, surmounting the challenge of sustaining an investment presence in the region requires juggling the paradox of being assertive in a competitive market and moderating protectionism, while upholding the principles of sustainable development. The enmeshed relationships and technological transformations of soft connectivity might provide an alternative zone through which the EU can explore new business opportunities and grow its influence, while supporting crucial trickle-down benefits across the region. In capitalising now upon its existing project management expertise, good relations with Kazakhstan, and innovative AI environment (stimulated and regulated by the landmark Artificial Intelligence Act), the EU, via the Global Gateway project, is well placed to take the lead in revolutionising this space and consolidate its role within the TITR.

Through being on the front foot in the route’s digital transformation, digital trade agreements can be instigated to protect investments and intellectual property early, secure them for longer, and develop beneficial policy relations. At the same time, however, the EU must ensure a lasting presence. Just as debt entrapment is a particular criticism of China’s involvement in the region, knowledge entrapment carries a weight of its own: ideally, the eventual handover should be the core principle of any project management investment by the EU. Through including facets of upskilling, the investments would not only be more sustainable, but more defensibly long-term. With 40% of its population under the age of 25, providing employment opportunities to the youth of Kazakhstan would not only stimulate the Kazakh economy as a whole, but in doing so reduce its overall dependency on Russia and China: greater economic autonomy in Central Asia is of significant benefit to the EU and the geopolitical dynamic of the region in general.

Concluding Remarks

To participate in the stimulation of Kazakhstan’s economy through soft connectivity investment is an exciting opportunity for the EU, and should be seized before it is too late. The ‘Global Gateway’ mission, which in its name suggests both an open door, and a finite channel which might be watched, influenced, and controlled, must conduct itself with an eye to investment longevity, sustainable development, and the role of the EU in the geopolitical frictions of tomorrow. In a global climate increasingly coloured by US-Sino relations and the tensions between Russia and Europe, the Middle Corridor is an imperfect but viable zone of possibility.