The ‘Biden-McCarthy Deal’: Is America’s Business Still… ‘Business’?

On June 3 2023 President Biden signed into law the ‘Biden-McCarthy Deal’, formally known as The Fiscal Responsibility Act (FRA; 2023) or H.R. 3746. The Act is the result of 6 months of debate in Congress and Congressional Committees, before Speaker of the House - Kevin McCarthy - and Joe Biden managed to strike a deal. Biden’s signature quelled his administration's second debt ceiling ‘crisis’, the first having occurred in late October 2021. The debate around the FRA highlights what is becoming a recurring theme in U.S. economic policy: ideological differences over non-economic policy leading to increasing economic policy uncertainty and ‘crisis’ events. For this reason, The FRA (2023) is being championed as a crucial moment for U.S. bipartisanship.

What the FRA Tells Us About Politics and the Economy

The FRA effectively suspended the debt ceiling until January 2025. Section 401(c)(1) gives the legal basis for much of already legally approved legislature and expenditure to be carried out, whilst Section 402(c)(2) prohibits The Secretary of the Treasury from issuing obligations until January 1 2025 “… for the purpose of increasing the cash balance above normal operating balances”. It is worth noting that The FRA is a long legal document, but Section 401 demonstrates the broad partisan compromises: the Biden administration and the Democrats can carry out their approved reforms and policies, and the Republicans got some of what they wanted in terms of limiting drastic money supply increases, quelling concerns of potential inflationary pressures arising from Biden’s policies.

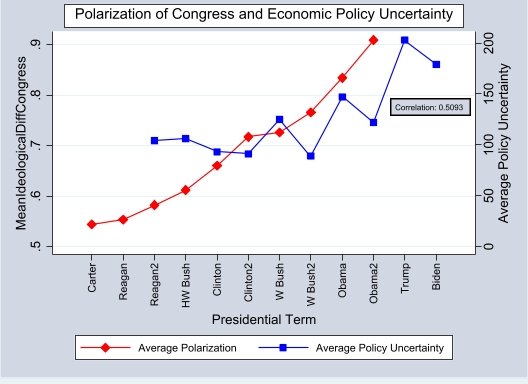

Rana Foroohar, Global Business Columnist and Associate Editor at the Financial Times, highlights that much of the debate around The FRA has been largely hung up “… on highly political issues such as defunding the Internal Revenue Service”. This draws attention to the fact that decades-long increases in political polarization is damaging the ability of the legislative branch to devise stable and predictable economic policies, which leads to recurring self-imposed debt ceiling ‘crises’ and government shutdowns that hamper investor confidence. Figure 1 visualises this increasing polarization and economic policy uncertainty:

Figure 1: Mean Ideological Difference (Polarization) of Congress and Average Economic Policy Uncertainty

The red curve uses data from Brookings to demonstrate the average ideological differences between both sides of the isle in Congress. The values used in Figure 1 were obtained by finding the difference in means of each legislature and plotting them against the corresponding term of the serving executive. Likewise the blue curve showing average economic policy uncertainty is a four-year average, corresponding to the four-year terms of the executives starting from the Carter administration. This data is obtained from Economic Policy Uncertainty (EPU) – a thinktank that specialises in political risk indices and indicators. The economic policy uncertainty index methodology comprises three components: automated analyses of media reports, the Congressional Budget Office’s publication of expiring tax code provisions, and expert sentiment around inflation and government purchases.

Of course, the data are descriptive and the positive correlation – 0.5903 – is not in and of itself indicative of any evident causal effect. Nor is data available for every administration. However, the challenges of recovering financially from COVID-19 and heightened political tensions at the qualitative level are a worrying sign that polarization is permeating economic policymaking. January sixth-esque events are not common occurrences in American history, and even shutdowns and risks of default have only become commonplace since the late 1970s. So if in 1925 the “chief business of the American people [was] business” then in 2025 the chief business of the American people will be politics.

Outlook for 2024: Yet Another Consequential Election

With the next potential debt ceiling ‘crisis’ set to come about in 2025, the eventual winner taking office after the presidential election in 2024 will have little time to get to work. Amid the ever-growing list of Republican candidates, former president Donald Trump and the Governor of Florida Ron DeSantis appear to be front-runners in the race. Asa Hutchinson is the next high-profile GOP candidate. On the other side of the aisle the incumbent Biden and Robert F. Kennedy, alongside Marianne Williamson.

At this stage it is still unclear what any of these candidates’ policies might look like considering there is still time to go until campaigning officially starts and intra-party housekeeping finishes. Of the candidates, the two most recent presidents do not have much to boast about economically. On the one hand, Trump inherited an economy at the apex of a growth trajectory and benefitted substantially from that fact prior to the pandemic. On the other hand, Biden inherited an economy with a post-COVID hangover and a war in Europe. Crucially, Biden is also having to contend with his counterpart in Beijing pursuing expansive foreign policies, flirting with de-dollarization.

Certainly, whoever is in office by February 2025 will have to navigate a turbulent macroeconomic environment domestically and internationally – as will transnational corporations and investors. “Political risk”, for corporates and investors, is becoming less of a concept attached to far-flung economies and is increasingly becoming a concept attached to what were once ‘stable’ economies in the West. The businesses who can best anticipate this will be the ones to best adapt to the global macroeconomic environment in the not-so-distant future.