Covert Naval Activities - Covert, Low Profile Military Vessels in the Littoral

This article aims to explore the ways in which state naval forces are employing various forms of non-traditional vessels in order to conduct hybrid warfare in the naval domain. Traditionally, naval power has been the essential tool in power projection and interstate military dominance with this power measured by the number of principal surface combatants (major military ships) possessed by one's navy. The nature of the increasingly surveilled and interconnected naval domain and world in general has created opportunities for irregular activities within it.

A particular area of interest is the littoral. The littoral refers to the area close to a state’s coastline encompassing amphibious operations in a military rather than geographical context. The UK Ministry of Defence defines the littoral zone as ‘those land areas (and their adjacent areas and associated air space) that are susceptible to engagement and influence from the sea’ adding a land component to the definition. Its significance is owed to the tendency of significant population centres, nodes of trade and communication, maritime traffic, and sea-based infrastructure to exist in this zone.

This article explores some of the methods and vessels used by a variety of states to conduct hybrid, grey zone activities in this area as well as further developments going forward and what this could mean for warfare in the 21st century. It furthermore explores vessels from a full spectrum of global navies namely; the US, UK, Iran and the PRC.

US Covert Special Operations Vessels

The US employs low-profile civilian appearance vessels for special operations activities. While the US has never denied their usage in a military role, they do not appear within the list of US navy vessels and have clearly been styled to maintain a non-militaristic appearance in order to avoid attention. The two vessels used, the MV Ocean Trader and MV Carolyn Chouest are both converted civilian vessels that sail without AIS (automatic identification system - publicly accessible ship trackers that all civilian vessels have installed) turned on in order to avoid tracking through open sources. These vessels have been retrofitted to conduct special forces activities through the installation of a flight deck and hangar for helicopters, launch bays for small military craft such as the Combatant Craft Assault (CCA), new signals intelligence (SIGINT) and communication equipment and berthing for special forces personnel.

There is very limited information available on the vessels or their activities, nor are there many official documents where these vessels are mentioned beyond their initial procurement requests. More interestingly, there are also very few photos available of the ships, with the MV Ocean Trader last photographed in Oman in 2018, and the MV Carolyn Chouest last seen in a photo released by the US Department of Defence in the Philippines in 2022. The near total lack of photos suggests that the discrete and uninteresting appearance of these vessels is successful at avoiding public attention and thus photography, assisted by the fact that the absence of AIS tracks prevents a concerted effort to track them through satellite imagery.

MV Ocean Trader, a BAE conversion of the formerly Maersk operated MV Cragside, was highly likely procured by US Special Operations Command to fulfil the role of a forward deployed base from which special forces activities in Africa and the Middle East could be conducted. This is evidenced by the temporary lease of a civilian ship from Edison Chouest Offshore to be statically based off the coast of Somalia until a converted ship could be acquired with the purpose of supporting special operations missions and conducting signals intelligence. The purpose of the MV Ocean Trader seems to be identical to the ship it replaced with facilities to land a number of special forces helicopters, carry special forces craft and launch drones. These operations could include, raids to strike high value targets (HVTs), diving operations, counter piracy and counter hijacking or boarding operations. The vessel has also been observed in the Mediterranean and Baltic Seas suggesting it has a special operations role to play here as well.

The advantage of the civilian appearance here is two-fold. Firstly, the vessel can move without drawing attention to itself as it transits the globe thus preventing any suspicion from adversaries as to its intended target or destination. More importantly, and more useful to its likely mission, it can provide basing for special forces in politically sensitive areas without attracting attention or driving political repercussions. For a hypothetical example, the MV Ocean Trader could remain anchored off the coast of Yemen collecting signals intelligence without suggesting it poses a direct military threat, and thus avoiding protest from groups in Yemen like a military-flagged warship would. It could then launch an unexpected raid into Yemen territory to remove an HVT before disappearing again into the clutter of civilian sea traffic. There is no indication that it has been used in this way, however, it certainly has the capabilities to be employed as such, and would be an invaluable asset in the 21st century environment where deniable operations are key.

Image 1: MV Ocean Trader in 2016 with a good view of the subtle military modifications while still retaining the overall appearance of a civilian cargo ship or ferry.

Image 2: MV Carolyn Chouest after conversion demonstrating very similar retrofitted equipment with the notable absence of a flight deck suggesting that the ship was likely converted for its availability and convenience rather than it being a perfect platform to operate from.

The MV Carolyn Chouest is a chartered vessel that originally supported the experimental research submarine NR-1 however was converted and repainted into a low-profile special operations support vessel. It seems to have a Pacific focus to its operations unlike the MV Ocean Trader and was involved in raiding exercises alongside partner nations as part of the Balikatan 22 exercise in the Philippines, suggesting that it’s primary purpose, similar to the MV Ocean Trader, is to support small scale special forces operations in the Pacific rather than the Middle East and Africa.

The Royal Navy has also expressed interest in a ‘littoral strike ship’, initial proposals of which are clearly based on the MV Ocean Trader. Important to note that this vessel is more overtly military and therefore not befitting the title of a covert vessel. It would, however, have similar capabilities as these US ships, demonstrating a view in the Royal Navy that these ships are incredibly useful even without the advantages offered by their covert nature in US service.

Iranian Covert Motherships

Iran, similarly, has become somewhat of a specialist in the usage of these disguised military ships. They employ both discrete civilian-styled vessels with military usage, and civilian vessels that have been overtly converted into military usage as floating ‘motherships’ for Iranian naval activities in the Red Sea and Persian Gulf. There is an important distinction to make between the two entities that conduct naval operations for Iran; the Islamic Republic of Iran Navy (IRIN) that conducts overt conventional naval activity and the Islamic Revolutionary Guards Corps Navy (IRGCN), which is largely focussed on covert, asymmetric, and hybrid naval operations in the region. The IRIN is largely analogous with other conventional navies, and is considered ‘green water’ rather than ‘blue water’, meaning it has the capabilities to operate regionally but does not have the assets or experience to claim global naval reach.

The IRGCN on the other hand is at the heart of regional asymmetric and unconventional operations and has been traditionally associated with activities such as swarm boat attacks, harassment of civilian and foreign military vessels, hijackings, smuggling of weapons to Yemen, and special forces operations. While the IRGCN does operate a fleet of overtly armed fast attack craft, the more important vessels are the two visually civilian cargo ships MV Saviz and Behshad.

Image 3: Behshad.

These two vessels, while appearing as civilian cargo vessels, are known to be operated by the IRGCN. Although the nature of their exact roles is unknown, open source intelligence and limited statements by the Iranian Government have been pieced together by intelligence analysts to give an idea of what they are involved in. These vessels seem to fulfil the same role with the Behshad taking over the role from the MV Saviz after it was damaged by an alleged Israeli sabotage attempt and forced to return to port. These vessels appear to fill the role of intelligence and observation ships that can sit in strategically significant areas, such as the Bab Al-Mandab strait on the Red Sea, and observe, document, and potentially interdict vessels travelling through the narrow sea lane.

The advantages that these vessels give Iran are enormous because the civilian nature of the ship means that it can remain in the strait indefinitely, while drawing little attention to itself and its activities. More specifically, the critical nature of this sea lane means that this vessel can act as a floating observation post where reports on Western, and more importantly, Saudi-UAE naval movements can be made to keep track of vessel locations and potentially facilitate windows of opportunity for deliveries of military aid to Houthi rebels, as well as observing Saudi-UAE aid to the Yemeni government. The ship’s radar system and possible signals intelligence (SIGINT) equipment would make it very effective at this task, as it could survey the entire width of the strait. In addition, this makes the vessel ideally placed to find potential targets for the IRGCN to seize, with numerous cases of Western vessels being boarded and moved to Iranian ports, or attacked. The presence of fast-attack craft seen on the deck of the MV Saviz seems to suggest that it would be capable of conducting these operations if a good target was located. The sabotage conducted on MV Saviz, whether conducted by Israel or not, suggests that these vessels are deemed enough of a security threat in the region that they warrant a military response. Further, the fact that Iran replaced the damaged MV Saviz with the Beshad within nine days signals that Iran sees these covert vessels as critical to their activities in the region as well, showing how effective and useful a covert naval asset can be.

While an overt naval mothership could also conduct these operations, the strength of the disguised vessels is in the plausible deniability they offer. With the ship seemingly unarmed and non-military in nature, it is able to provide the Iranian government with the ability to deny it is engaged in military activity in the area. This deniability is clearly useful in the event of a vessel seizure or weapon shipment seizure where Iran can claim that it had no military assets in the area and therefore, to a general audience, seemingly convincingly deny involvement and thus not elicit a major military response.

People’s Armed Forces Maritime Militia

Another geographically distinct example of this kind of vessel use is seen with the Chinese People’s Armed Forces Maritime Militia (PAFMM). The PAFMM is a paramilitary organisation that consists of a mixture of purpose built militia ships and modified fishing trawlers that is designed to augment People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN) activities, especially in the South China Sea. The fleet likely numbers in the thousands, with the vast majority consisting of unarmed fishing trawlers. The role of this organisation appears to be to intimidate foreign naval vessels in order to project Chinese naval power without the need for the higher profile of involvement from PLAN vessels. They achieve this through swarming, harassing, ramming and blocking other states’ naval vessels in the South China Sea. Similar to the previous examples, these vessels give the Chinese government the ability to conduct effective grey zone warfare by having naval assets that are plausibly not under direct government control therefore not drawing as large a military response as a PLAN vessel would.

Image 5: PAFMM Vessel harassing the USNS Impeccable in 2009.

A classic example of the work of this fleet is the Scarborough Shoal standoff in 2012. In this particular case, Chinese fishing vessels, which were deemed by the Philippines to be fishing illegally, were searched by Philippine Navy personnel. However, when the Philippine Navy attempted to arrest the fisherman, PAFMM vessels physically blocked the ships and used water cannon to force the Philippine vessel away. Following this, consistent disruption efforts by PAFMM vessels have led to the shoal coming under de facto control of China where Philippine fishing vessels are unable to fish the area, while an estimated fleet of 287 Chinese fishing vessels fished the area in 2021. This demonstrates the effect such strategy can have, as harassment tactics rather than direct military confrontation elicit a lesser international response, and therefore allow China to achieve its maritime aims without serious diplomatic or military consequences.

Anti Access Area Denial

To fully understand the effectiveness of these US, Chinese, British and Iranian vessels, it’s essential to introduce the concept of anti-access and area denial (A2AD). A2AD is, in its simplest form, the controlling of access to an area by a military force. This is often thought of in terms of weapons systems that could be employed asymmetrically by a weaker force to prevent a stronger force accessing a certain area to conduct operations. A good example of this would be the use of anti-ship missiles (ASMs) where the threat of missiles fired from land could deny a naval force the ability to operate within the missile’s range of the coast. This can be seen in Ukraine, where the efficacy of Ukrainian naval A2AD systems in allegedly sinking the Moskva have limited the vastly superior Russian naval forces to long range strikes, and have denied them access to conduct amphibious operations against the Southern Ukrainian coastline. Whether the Moskva was indeed sunk by Ukrainian ASMs or otherwise, the relegation of the Russian Black Sea Fleet to a series of platforms for launching cruise missiles rather than engaging in littoral operations suggests that Ukraine has successfully leveraged its A2AD assets to deny the Russian forces a domain in which they command complete supremacy.

Image 6 displaying the different layers of the Chinese A2AD bubble in Pacific Asia. These assets could be used to deny Japanese, Taiwanese, South Korean and US navies access to the region and render operations within the bubble impossible due to the threat of casualties from these systems.

In the context of these covert vessels, the advantage they offer is that they can operate within, and threaten an adversary A2AD bubble. This is explored in depth in a Royal United Services Institute (RUSI) publication where the concept of a low profile, lightly armed, covert vessel (titled the littoral operation vessel (LOV)) could enter a contested region without eliciting a major military response from an adversary and then conduct low-intensity, grey zone operations to set the conditions for future large-scale military activity or contest opposing grey zone operations. Applying this idea to the examples above gives a set of possible scenarios which can illustrate the importance of these vessels. The MV Ocean Trader could forward deploy to the Middle East and sit without indicating a major US military deployment. On the vessel could sit a task force of US special forces personnel, helicopters and small boat assets that would enable counter piracy, interdiction and sabotage operations. This is particularly significant in the context of the recent US announcement of their intent to deploy small protection teams on civilian vessels transiting the Persian Gulf. The MV Ocean Trader would be perfectly positioned to blend into the mess of civilian traffic and deploy these small teams, as well as directly countering Iranian efforts to threaten shipping by engaging in activities that would be politically damaging to attribute to conventional US naval assets, such as engaging in sabotage or reconnaissance of Iranian fast-attack craft bases. Further, the persistent deployment of this vessel would set a pattern of life that would potentially allow it to operate within the Iranian A2AD bubble, as directly challenging a non-threatening US vessel with ambiguity and deniability in its activities would set Iran on an escalatory path and justify further US actions. If direct confrontation between Iran and the US became necessary, this would allow the US to deploy small special forces teams to destroy Iranian A2AD and shape the battlefield for a future conventional naval task force. The concept follows the same logic for the British Littoral Strike Ship/LOV concept, with three worked concepts found within the RUSI article.

The PAFMM is similar in its ambiguity. Deniability from the central government combined with confusion on ownership, identity of vessels, justification as a military target and autonomy from the PLAN means a PAFMM vessel or fleet isn’t going to cause a direct military response or justify the employment of A2AD assets from a neighbouring navy. Instead one gets below-the-threshold-of-conflict engagements between these vessels and their opponents, consisting of water cannon, ramming, shining of laser, physical blocking and attempts to foul the propulsion systems with nets. In other words, exercising naval power without firing a shot. Overall, these vessels, and those mentioned previously, rely on a perceived lack of threat, operational ambiguity, disguise, deniability and persistent deployment to create enough confusion and uncertainty to prevent an adversary from engaging in military or political response by utilising their A2AD systems, without seeming to be the escalatory power themselves. Thus, they create a dilemma where they either don’t respond and allow the grey zone activities to continue, or escalate, which, in turn, paints them as the aggressor and/or justifies further escalation from the original operator of the covert vessel. A third option is to deploy an opposing asset to conduct countering grey zone activities such as the fate that befell the MV Saviz where, likely Israel, countered Iranian deniable activities with their own deniable attack on the vessel, leading to no escalation from either side and no claiming of responsibility for these actions.

Modularity

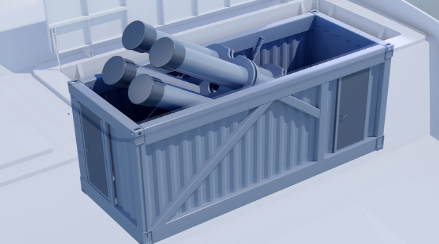

A relatively recent naval development that lends even greater significance to these vessels in the roll out of a number of containerised modular systems designed to fit within a 20 or 40 foot standard shipping container space and offer a full spectrum suite of naval sensors, weapons, unmanned systems and countermeasures. The following briefly explores the capabilities offered by the SH Defence CUBE system as this seems to have the greatest integration from other defence manufacturers as well as being the most mature system.

Two images demonstrating the capabilities of the CUBE. Image 7: Sea mine deployment. Image 8 (below): Anti-ship missiles.

With sufficient power generation to run, this system effectively allows any vessel to fit military systems at short notice, or an existing military vessel to enhance its capabilities. A covert vessel would raise very little suspicion with a cargo of a few containers placed on its deck, and it would not detract from the low-profile appearance of the vessel. Yet, these containers could give these vessels full spectrum naval capabilities with air defence, anti-ship or land attack missiles, armed unmanned vehicles, extra attack craft to carry extra special forces, naval mines or sensor systems such as an electronic warfare suite or radar. All of this would be possible within an adversary A2AD bubble. It is important to note that part of the low-profile nature of these ships comes from their lack of overt weapons systems. Therefore, while these modular containerised systems would provide a potent asset, their usage would be one-off before justifying the covert vessel as a legitimate, overt military target. In an amphibious warfare context, however, this brief surprise may be all that is required to achieve an operational objective.

One key issue with this system is target identification. While a navy’s armed surface combatant fitting two containerised air defence missile systems is not problematic regarding military identification, setting the precedent of deploying such a system to a civilian appearance vessel allows the leap to be made justifying any civilian ship with a container as a potential military target. This is clearly an unacceptable situation in the eyes of Western navies, hence the lack of weapon systems on the US and UK vessels presented in this article. The Russian Navy has however, indicated their willingness, or at least consideration, of fitting these systems to a civilian vessel as demonstrated by this graphic.

Image 9: Graphic demonstrating how this system could be fitted to a civilian vessel and blend in with other shipping containers and deliver four anti-ship missiles.

This highlights the important point of the balance these vessels must strike between appearing civilian enough to maintain a low profile and yet still be somewhat attributed to a military entity in order to avoid justifying actions against civilian shipping.

Conclusion

Overall, these vessels, while differing in their intended tasks, their capabilities, and their level of militarisation, have been developed to operate within the same domain. They are designed to operate below the threshold of conflict and provide a capability to operate in the grey zone through deniability, secrecy and ambiguity. They provide an ability to project soft power as well as low-intensity hard power to further a state’s objectives without provoking a significant military or political response. This ability allows them to operate within an A2AD bubble in a peacetime environment, or threaten the destruction of the bubble in a warfighting environment.

With the ongoing increase in multipolar, low intensity, competition across the globe, and the decline of the US as definitive principle naval power, the importance of possessing assets able to achieve political and military goals without sparking major conflict in the littoral zone will continue to increase in relevance. We may be expected to see, or not see, an increase in the number and scope of operators of these vessels in the coming decade.

Warfighting and Irregular Warfare in the 21st Century

The nature of warfare has been perpetually altered by continuous innovation in technology and strategy throughout history, never remaining static for long periods of time. This rate of change, however, vastly accelerated during the 20th century seeing a change from cavalry and bayonet charges through nuclear weapons to stand-off precision weapons and cyber warfare. This article will explore some of the key foundational concepts of 21st-century warfare and provide a concrete set of definitions on which this series will base its analysis. It will then explore the scope and range of topics that will be covered in the series going forward and provide a brief overview of Ukraine in order to ground these topics in a conflict currently taking place.

Some definitions

To set the conditions for a comprehensive analysis of these changes, it is first necessary to provide some concrete definitions for often misunderstood or misused terms relating to the topics of irregular warfare and warfighting.

Warfighting

Warfighting, as the name would suggest, refers to the action of fighting a war, specifically and crucially this conflict is through kinetic means with physical military engagement between belligerents. The UK Ministry of Defence states “while the character of warfare is changing, the nature of war does not change, it is always about the violent interaction between people.” This highlights the key point in this term that warfighting is not conflict or contest between groups but rather, actual direct military action. The term ‘conventional warfighting’ will also be used throughout this series to refer to so-called “peer” and “near-peer” warfighting, i.e. warfighting against an adversary considered to be militarily equal or near-equal in terms of capability. A traditional example of this would be, from a US perspective, China as a peer adversary or Iran as a near-peer adversary.

Hybrid Warfare

Hybrid warfare is not a doctrinally defined term within a Western military context, rather it is a concept developed by Frank Hoffman to describe the emerging threat of multifaceted military entities in 21st-century conflict. He talks specifically about the blend between conventional warfighting, irregular warfare, and terrorism or organised crime. Specifically, he describes hybrid warfare as being conducted by state or non-state actors and involving an ambiguous mix of combatants and tactics to exploit military vulnerabilities in a force. While he uses the example of Hezbollah in 2006, a more current example would be the Russian forces deployed in Ukraine where a large conventional Russian Armed Forces (RuAF) element is augmented by militia forces from the Luhansk and Donetsk People’s Republics (LPR and DPR as well as mercenaries from the Wagner Group amongst others). The term hybrid warfare is often deployed in a context of national competition below the threshold of conflict such as economic warfare, energy warfare or political interference. This is beyond the scope of both Hoffman’s definition as well as the range of this article series and as such we will focus on the, primarily, military nature of Hoffman’s definition.

This form of conflict is becoming increasingly common as states seek to conduct military operations without the domestic and political risk of their state military involvement. These militias offer a level of deniability along with leveraging existing local disputes, power structures and sentiments to increase the chance of military success. Another current example would be that of the ongoing conflict in Syria where various militia factions are supported to varying degrees by the West, Turkey, Iran and the Syrian government itself with international state involvement including the US, Russia and the UK supporting these factions with air-strikes and troops on the ground. It is difficult today to find or imagine an active conflict that does not correspond to this definition. On the contrary, it has become an essential element in conduct of warfare, as irregular forces are often capable combatants and can cause difficulties for conventional military forces.

Irregular Warfare

Irregular warfare has traditionally been used, incorrectly, to describe all military activity that does not fit within the traditional view of conventional warfighting. The Modern War Institute defines it as “a coercive struggle that erodes or builds legitimacy for the purpose of political power. It blends disparate lines of effort to create an integrated attack on societies and their political institutions. It weaponizes frames and narratives to affect credibility and resolve, and it exploits societal vulnerabilities to fuel political change. As such, states engaged in or confronted with, irregular warfare must bring all elements of power to bear under their national political leadership.” The key point is that this form of warfare involves various techniques and groups that are not considered conventional and can, but does not necessarily have to, involve violent conflict. Examples of techniques that could be considered irregular warfare would be the spreading of disinformation to reduce legitimacy of a military group. An example could be the Russian focus on and inflation of the far-right elements of the Ukrainian military to portray the entirety of Ukraine as a far-right state despite that not being the case overall.

Asymmetric Warfare

Asymmetric warfare has a simple definition but two completely different military situations in which this definition can be applied. Kenneth McKenzie Jr defines it as “leveraging inferior tactical or operational strength against [the] vulnerabilities of a superior opponent to achieve disproportionate effect.” While this in itself is a fairly tangible definition, the nuances of this term are in what is being considered asymmetric. For example, a war between a nuclear and non-nuclear state could be considered asymmetric even if the belligerents were equal in conventional military power. Similarly, any war involving the US could be considered asymmetric given the unmatched scale of the US Air Force (USAF).

For this series, asymmetry will be used in three ways. Firstly, strategic asymmetry. This concept can be used to describe warfare between two fundamentally unequal military groups where one side is totally outmatched in every metric. An example of this would be the conflict between the International Security Assistance Force (ISAF) and the Taliban within Afghanistan where ISAF outmatched the Taliban in technology, funding, manpower, training and equipment. It is important to note here that strategic asymmetry does not guarantee defeat for the weaker side as this example illustrates.

A second use of the term asymmetric warfare is that of operational or tactical asymmetry. This can be broken down into asymmetry in tactics, techniques and procedures (TTPs) and asymmetry in physical metrics such as equipment or manpower figures. Asymmetric TTPs can be used to describe the situation in which belligerents with a level of conventional military equity seek gains by changing tactics to exploit a perceived weakness. For example, the Ukrainian Kharkiv counteroffensive exploited a perceived stretching of weakened Russian defensive lines by massing lightly armed vehicles with high operational mobility to penetrate and exploit the Russian lines achieving rapid victories. This tactic would not be found in any Soviet, Russian or Ukrainian doctrine handbook and instead capitalised on the available equipment and condition of the battlefield to defeat an opponent expecting a conventional attack.

Further, asymmetry can be used to refer to a disadvantage or difference in a specific physical measurement of military power. This could include a disadvantage in the numbers of troops, equipment or ammunition such as the artillery barrel and ammunition deficit that left Ukraine facing a 10:1 disadvantage around Bakhmut or a specific capability gap such as Ukraine’s lack of a blue water navy or any navy at all. These asymmetric disadvantages leave room for asymmetric innovations and technologies to fill, many of which will be explored in this series.

Unconventional Warfare

Unconventional warfare refers specifically to activities designed to support an insurgency or resistance group in order to achieve political and military goals. It is an element of irregular warfare.

Grey Zone Warfare

Another poorly doctrinally defined yet widely used term. Grey zone warfare has been explained by the Australian government as “activities designed to coerce countries in ways that seek to avoid military conflict... paramilitary forces, militarisation of disputed features, exploiting influence, interference operations and the coercive use of trade and economic levers.” This essentially overlaps with the definition of irregular warfare but refers more to the non-physical domain in which this activity occurs; the ‘grey zone’. A key point here being that this definition is self-contradictory, stating that grey zone warfare seeks to avoid military conflict but advocates militarisation and interference operations as acceptable tactics. The point this definition is trying to get at is that grey zone warfare seeks to avoid conventional military conflict. The Nord Stream bombings were almost certainly a military operation of some kind regardless of speculation of actors involved, however this activity was designed to add a layer of deniability in order to get a state-on-state advantage without escalating to conventional war.

There is significant overlap between these definitions, some of which are based on existing military doctrine and others which have been created as theoretical tools to group together certain types of military activity.

The diagram below is intended to visually illustrate the overlap of some of these terms and theories and to show how various military actions can be categorised into a certain form of warfare.

Matrix of Conflict. Source: Australian Army Research Centre

Scope of this series

This series will explore a variety of TTPs, technological innovations, and changes in military force design that have occurred or may occur in the near term at tactical, operational, and strategic levels. It will illustrate how the changing nature of conflict has influenced and will continue to influence military development in technology, equipment and TTP in the future. The focus will be on the military aspect of these changes rather than the political aspects covered in the Hybrid Warfare series. The series will largely explore topics relating to the Russian invasion of Ukraine, as it is the most recent crucible in which these changes can be observed and from which these innovations have, are and will emerge. These lessons and observations can then be applied to other regions of the world to examine their impact on warfighting in the 21st century more generally.

Ukraine as a case study for irregular warfare

The Ukrainian conflict is an ideal case study for examining the various forms of warfare defined above and the physical manifestations of these forms of conflict.

The Ukrainian conflict encompasses all the forms of warfare that this series seeks to cover, from targeted assassinations in Moscow to the destruction of critical national infrastructure and the development of improvised or homemade naval and unmanned aerial systems. While it is not the intention of this series to focus entirely on Ukraine, the conflict provides the most recent evidence base from which lessons can be learned and developments in technology and TTP can be observed. Moreover, the war in Ukraine has provided perhaps the first example of real warfare in the 21st century and has proved to be a theoretical watershed moment as traditional post-Global War on Terror Western thinking sought to distance itself from conventional warfare in Europe and focus on irregular warfare in the Indo-Pacific, as the Integrated Review illustrates. The Russian invasion brought an interesting change to this view, forcing Western states, while not discounting the rising threat posed by China, to accept that the idea of interstate conflict in Europe is not as distant as once thought.

At an operational level, the war in Ukraine has proved another assertion about 21st-century conflict wrong. The idea that conventional warfare is still relevant was relegated to the background in favour of expeditionary, asymmetric, and interventionist warfare as demonstrated in Iraq, Afghanistan, Libya, Mali, and South Sudan among others. What Ukraine has shown is that while conventional warfare is still of crucial importance, its nature has entirely changed, as we will see in other articles. 2,000 destroyed, damaged or abandoned Russian tanks would seem to suggest that the TTPs, technology or equipment that the Russian Armed Forces (RuAF) have employed so far are fundamentally challenged in the conventional warfighting environment of the 21st century and that there are many lessons to be drawn from their actions, failures, and successes.

The conflict has also provided numerous opportunities to observe asymmetric warfare in action, with examples such as the use of custom-built unmanned surface vessels (USVs) by the Ukrainian army to challenge the Russian Black Sea Fleet or the procurement and employment of Western air defence systems to counter the threat posed by the Russian Air Force and Russian long-range precision guided munitions (LR-PGMs) such as Kalibr, Kinzhal or Iskander-M missiles. This asymmetric tool employed by Ukraine has denied Russian forces air superiority, a key tool that facilitated the allied success in Desert Storm.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this brief introduction to the terms and primary case studies to be used throughout this series aims to have provided a basic conceptual understanding of the spheres of conflict that sit below and alongside the conventional understanding of warfighting. Going forward the series will explore a variety of domains and specific examples of technologies and strategies that exist within these spheres and the impact that these will have on warfighting and conflict in general going forward. These examples will be explored at a variety of scales with innovations at the strategic, operational and tactical levels as well as exploring entirely new domains of conflict such as deep sea warfare.

As the conflict in Ukraine is currently demonstrating, irregular and unconventional warfare is likely to become more prevalent in the coming decades even as conventional interstate conflict continues as a major security threat. As the conflict continues, new material and tactical developments continue to appear driven by the combination of limited economic and military resources on both sides as well as the push to achieve a military advantage and improve the situation on the battlefield.

These developments in Ukraine are being watched globally by various militaries to form the basis for new policy, procurement decisions, and military innovations to move from the traditional Cold War model of interstate warfare to the hybrid forms seen today. The successes and failures of these developments, and their applicability to other potential and current theatres of conflict, will pave the way and shape the nature of 21st-century warfare.