Ukraine’s Journey to Recovery and Accession: Looking Ahead Following URC 2023

“Ukraine is re-building now… not only to repair what was lost, but to stride forward.” These were the words of the Rt Hon James Cleverley at the Ukraine Recovery Conference (URC) 2023 (titled the Ukraine Reform Conference in previous iterations), hosted jointly by the United Kingdom and Ukraine in London last month. It is a mark of Ukrainian resolve that their concentrations are not only focussed on the short-term ambition of winning the war against Russia and securing their international border, but staking out a long-term plan, one which is underpinned by more than just ‘vision’, one – as President Zelensky states – which focuses on “agreements, and from agreements to real projects.” The tone is resolutely one of transformation towards a new future, using the conflict as a catalyst to turn Ukraine not only into a pillar of Western international organisations such as NATO and the EU, but also into a bastion of security, unity, stability, democracy, and growth in Europe.

The Cost of the War

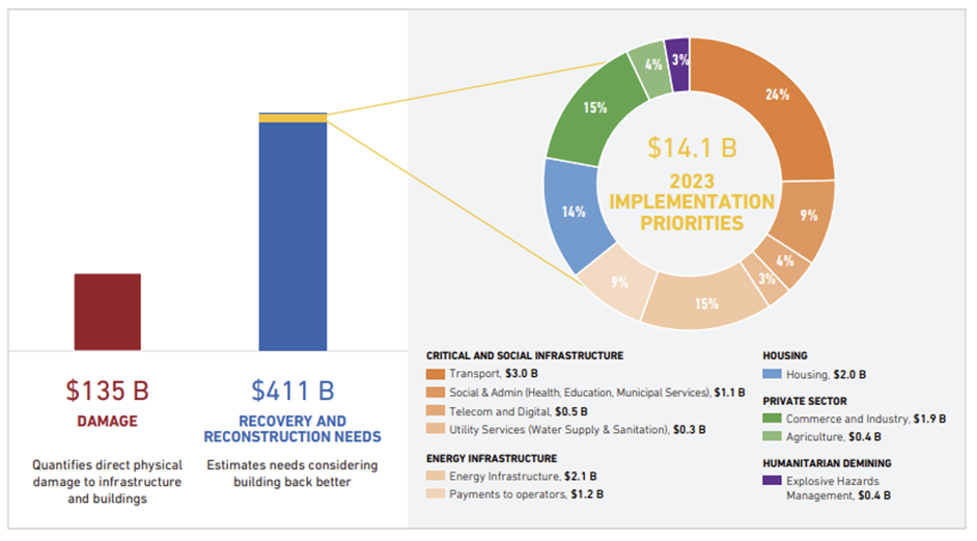

A little over one year after Russia’s full-scale land invasion of Ukraine, the World Bank conducted a second Rapid Damage and Needs Assessment (RDNA) – an estimate of Ukraine’s reconstruction and recovery needs. The estimate, which included the investment needed to meet European Union (EU) economic alignment policies, ran to $411 billion, though the Prime Minister of Ukraine, Denys Shmyhal, suggested this figure could double once Ukraine has liberated all its territories.

Figure 1. RDNA key results: damage, needs and 2023 priorities. Source: World Bank

Foreign financial aid to the tune of $60 billion has already been agreed by the EU, UK, US, Switzerland and others, cohered through the Multi-Agency Donor Coordination Platform for Ukraine. An evident shortfall exists. As the extent of damage across Ukraine grows, inferences to a US-style Marshall Plan have become more and more pronounced. However, The Marshall Plan, when run through today’s inflation calculators, costs less than one-third of the World Bank’s RDNA estimate. The shortfall can only possibly be made up by private sector investment. Whilst the idea of forced reparations is being heavily debated, there is currently no legal precedent for using frozen Russian assets in such a way, and any proposal would have to have the nod of agreement from the US, which is uncertain.

Private Sector Investment

Attracting private sector investment was described during the conference as “essential”. The conference was in reality a ‘call-to-arms’ to mobilise support from the private sector. There are early positive signs, with asset management companies such as J.P. Morgan and Blackrock drafting initial development fund proposals to encourage capital investment exclusively for Ukraine’s recovery. Immediately after the conference ended, a number of high-net-worth individuals and tech sector agencies publicly announced their intent to push forward with investing, including VEON, the Dutch telecommunications company, and Andrew Forrest, the Australian mining mogul and philanthropist (the latter on the condition Ukraine is able to decisively stamp out its economic corruption). Other significant names in the free market have signed up to the Ukraine Business Compact 2023, which, as stated by signatory Rothschild & Co., will “enable Ukraine to modernise, build a resilient and agile economy and emerge from the current conflict as a strong and prosperous state.” In tandem, Ukraine has set in motion its own Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) incentive programme, known as ‘Ukraine Invest’, which amongst other incentives includes a 5-year corporate income tax exemption for investments over $10 million in privatisation projects, VAT and customs exemptions for equipment and machinery imports, reduced interest loans for Small-Medium Enterprises (SMEs), government collaboration for investments over $100 million and incentivised land tax rates.

Though the early signs appear positive, a significant hurdle to private sector investment will be the cost-effectiveness of reinsurance policies in lieu of security guarantees. As of January 2023, reinsurance costs had risen by as much as 200%, a trend which is only likely to stagnate or even rise. Aerospace, property and shipping industries in particular – the latter especially salient owing to Russian-led embargoes in the Black Sea – have suffered from the hikes in reinsurance costs. Reinsurance re-negotiations will have almost certainly been made significantly worse with the breach of the Nova Kakhovka Dam and subsequent environmental and property damage, as well as the catastrophic consequences of a potential major nuclear incident at the Zaporizhzhia Nuclear Plant. Key developments during the conference did address this problem. Several initiatives were launched, including The London Conference War Risk Insurance Framework. There was renewed emphasis on the World Bank’s Multilateral Investment Guarantee Agency (MIGA) ‘Support for Ukraine Reconstruction and Economy Trust Fund’, to which the UK and Japan are significant contributors. The European Bank for Reconstruction & Development (EBRD) also announced a pilot war risk insurance scheme.

NATO Accession

Ukraine’s recovery and its aspiring accession to the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation (NATO) are inextricably linked, with the rhetoric ramping up ahead of the NATO summit in Vilnius this month. President Zelenskyy had a very clear message for NATO Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg during the European Political Community Summit in Moldova on 1st June; “When there are no security guarantees, there are only war guarantees.” The UK in particular have been vocal in supporting Ukrainian accession to the alliance, advocating for a removal of the traditionally mandatory Membership Action Plan (MAP), to allow Ukraine to be fast-tracked through the joining process. Significant hurdles exist, however. Aside from the UK, and to an extent, the US democratic vote, scepticism remains high among some European NATO members. A poll run in France, Germany, Italy, and the Netherlands by the New Europe Centre in Kyiv showed support for Ukraine joining NATO once the conflict has ended sits at around 50%, a figure which drops by half once the caveat of “as soon as possible, even if the war with Russia is ongoing” is added. Additionally, Ukraine is fighting in an active conflict. Stoltenberg has made it very clear that the condition of not being in an active conflict prior to accession is upheld, and an exception is not on the agenda. This has always been a cornerstone of NATO accession policy, to ensure that members are not immediately drawn into a NATO Article 5 situation when a state at war joins. An additional complication is the threat of Hungary holding up Ukraine’s bid, in much the same way as Turkey has been holding up Sweden, citing concerns over the rights of Hungarian speakers in the country. The Transcarpathian region of Ukraine is home to some 150,000 ethnic Hungarians. Many see themselves as persecuted, particularly by Ukraine’s recent law mandating the use of Ukrainian in school classes. Whilst this was a measure implemented primarily to distance Ukraine further from Russia, it has also marginalised the Hungarian-speaking communities, something Viktor Orban has been quick to raise.

That said, progress in Ukraine’s ambitions to join NATO during the Vilnius Summit would likely prove useful for Ukraine’s recovery. NATO membership – or an obvious pathway to membership once the conflict has cooled – will substantially boost investor confidence. Security guarantees and the prospect of relatively imminent NATO membership are seen by Ukraine as critical to private investors accepting risk without having to rely on vast insurance fees.

EU Accession

The EU and its Member States are leading proponents of Ukraine’s recovery, with President of the European Commission Ursula von der Leyen stating that “investments will go hand in hand with reforms that will support Ukraine in pursuing its European path.” She has also set a target for Ukraine’s accession within four years. Ukraine continues to make progress – having been granted candidate status – with EU Commissioner for Neighbourhood and Enlargement Olivér Várhelyi declaring that Ukraine is "on track", but acknowledging there is still work to be done. Of the seven conditions Ukraine must meet to achieve full member status, it has so far met two; media reform and judicial reform. The latter has arguably been only partially successful, with additional work required to separate the newly formed Constitutional Court from the Presidential Office, in the interests of ensuring an impartial judicial selection process. The remaining conditions to be met will require Ukraine to bring its entrenched corruption under control. Ukraine has undergone a near-total upheaval in its pre-2014 investigation and prosecution procedures. Spurred by prospects of joining the EU, the last eighteen months have seen an acceleration of prosecutions, despite the ongoing conflict.

Member State governments are quick to remind the EU leadership that any deviation from due process poses a risk. Denmark, in particular, is determined not to see a lowering of standards as a means of accelerating Ukraine’s accession. Lars Løkke Rasmussen, Denmark’s Minister of Foreign Affairs, has warned of the risks of “importing instability” with regards not only to Ukraine’s bid, but also that of Moldova, Georgia and the Western Balkans, and that “geopolitical circumstances did not justify skating over governance reforms”. In a similar vein, Austrian ministers Alexander Schallenberg and Karoline Edtstadler stated in a letter to High Representative of the EU for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy Josep Borrell that Ukraine should not be given preferential candidate status over other aspiring member states in the Western Balkans. Political commentators such as Jacob Kirkegaard of the Peterson Institute for International Economics have also postulated that before the EU admits new members, more qualified majority voting systems and greater fiscal integration may be needed, to avoid belligerent members frustrating conformity, such as Hungary, which refused to agree to the Russian oil embargo following the invasion.

Implications

Much of what has been discussed will depend on the length of the conflict. From an FDI perspective, a protracted war may well lead to investor fatigue, or even a normalisation of business-to-business relations with Russia, which as Richard Branson made clear during Plenary 1 of the URC, is “contributing to Putin’s war chest”, increasing the longevity of the fighting. Similarly, the bulk of FDI, especially initial investors, are likely to begin in the West and only move East as it becomes safe to do so. This risks creating an East-West investment divide, which would mirror other East-West divisions; language, history of the electorate, and levels of destruction. For FDI not to become a divisive issue, Ukraine will need to be conscious of the distribution of investment. This could be amplified when looking at where Ukraine’s resources exist. In March 2022, over 30% of all Ukrainian exports consisted of coal, metals and minerals, the vast majority of which comes from the heavily contested Eastern Dnieper-Donetsk region. During the URC, a notable line of operation was building a greener economy. The Co-Chair statement speaks of the Government of Ukraine being “determined to build back a more modern, innovative, green economy, closer to the EU Single Market… [with] G7+ governments committed to develop a new Clean Energy Partnership with Ukraine to accelerate the transition to a green energy system that is secure, sustainable, resilient and integrated with Europe.” With the security of Ukraine’s mineral-holding regions under long-term doubt, Ukraine may need a green energy focus, not only to meet EU benchmarks, but to attract investors and reacquire a degree of energy security.

NATO too must be conscious of a protracted conflict. Polling in the US, which is by far Ukraine’s most significant supporter in terms of military, humanitarian and financial aid, shows that two in five Americans (41%) hold a more isolationist perspective, with a view that the problems in Ukraine are not American business. This figure could begin to rise if the military aid is seen to be having little to no effect on Ukraine’s counter-offensive, and the outcome of the US presidential elections next year could lead to further disenfranchisement, which could hamper Ukraine’s ambitions for joining NATO. We are also likely to see tension during the Vilnius Summit between hardline advocates for rapid Ukrainian accession – likely spearheaded by the Baltic States and Poland – and the more cautious NATO core of the US, Germany and France, with opinion divided over Chapter 1, Paragraph 5 of NATO’s ‘Purposes and Principles of Enlargement’, which states that new members must “settle any international disputes in which they may be involved by peaceful means in such a manner that international peace and security and justice are not endangered”, and that the “resolution of such disputes would be a factor in determining whether to invite a state to join the Alliance.” Given Stoltenberg's red line that accession is not possible until the conflict is over, it seems unlikely that the hardliners will get a timeline for accession in the near future. It is more likely that a possible invitation to Ukraine to join will be re-emphasised, with the only significant decisions being whether Ukraine will have the MAP waved and whether NATO will commit to providing additional security guarantees in the form of additional training and equipment. That being said, France is understood to have held a Defense Council meeting in early June which proposed accelerating Ukraine’s accession to join the EU as an alternative security guarantee in its own right, pulling Ukraine further into Europe’s orbit. It is argued that, whilst risky, assisting Ukraine in going ‘past the point of no return’, could put Ukraine out of reach for Putin, and even encourage a shorter end to the conflict.

Final Points

The paradox of Vladimir Putin’s invasion of Ukraine is that instead of slowing Ukraine’s post-Euromaidan agenda, he has accelerated it. Although hurdles remain, Ukraine’s governmental and judicial reforms, its EU and NATO accession prospects, its standing army (and its competence) have all undergone radical changes in a Westward-leaning perspective, and all despite the conflict. European institutions have been quick to provide not only military and humanitarian aid, but also financial aid for recovery and assistance with reform. Private investors have already directly intervened to Ukraine’s military advantage (Maxar Technologies, Starlink and others), but now they are also actively involved in Ukraine’s recovery and its future vision. URC 23 marked an important shift in the language used throughout the conflict. It is no longer just about Ukraine’s survival. It is about putting Ukraine on the path to a European free market democracy. The conference confirmed the existence of a wealth of private sector support, recovery processes, and reinsurance frameworks. It remains to be seen what impact this will have on the $411 billion recovery and reconstruction cost. URC 23 also proved to be a useful cross-check on Ukraine’s EU prospects, with a reiteration of its commitment to reform, progress to date and accession negotiations taking place this year.