Antarctic Claims: Historic claims, contemporary challenges- France and the UK on the South Pole

As part of London Politica’s Geopolitics on the Periphery Programme, our newest addition, the Antarctic Claims project is set to examine the geopolitical implications surrounding the division of the world’s least populated continent. This project consists of four articles organised in a series, each approaching the issue from the perspective of one or two countries that have any direct claims in the land. This is the first out of the four articles, discussing the UK’s and France’s involvement in Antarctica.

In 1908, the United Kingdom, and slightly less than two decades later, in 1924, France drew up claims concerning the territory of the Earth’s southernmost continent, marking the first two of the seven states to declare their official sovereign interest in Antarctica. Around a hundred years later, while both countries consider the issue of their Antarctic claims a matter of national interest, a substantial difference in the expression of this now exists between London and Paris. Seemingly, whereas the former has clear objectives regarding the land, the latter’s ambitions are – as Martin-Nielsen (2021) pointed out – “far from decided”.

Analysing France and the United Kingdom’s approaches to the Antarctic not only allows an uncovering of the reasons why the Antarctic was, and indeed still is, of particular interest to major states, but also reveals important insights into the geopolitics of Antarctica itself, in particular, how the situation of two economically and strategically similar states in the region can be so different.

The lands claimed

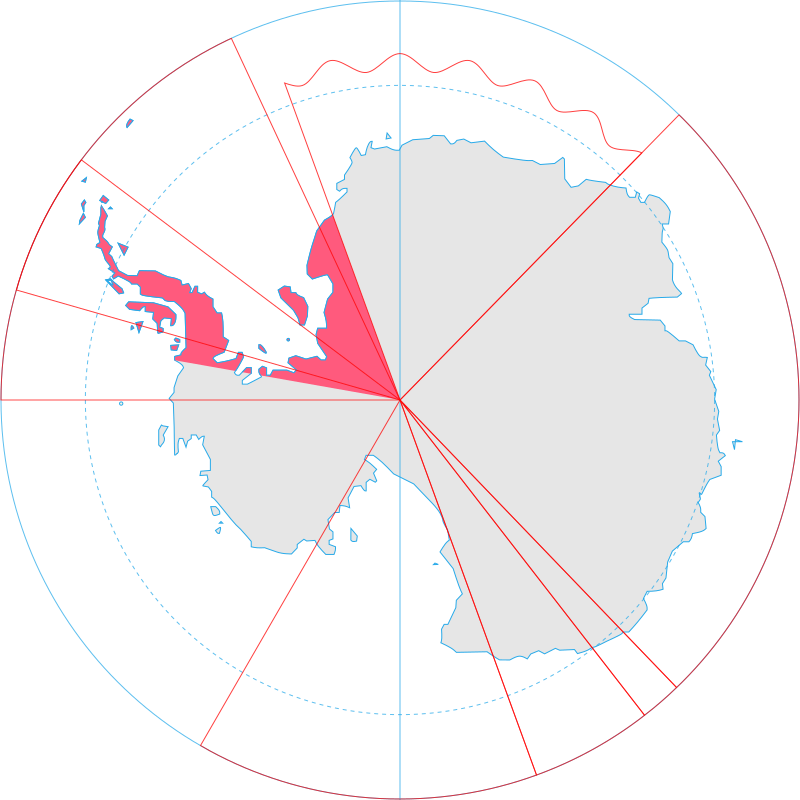

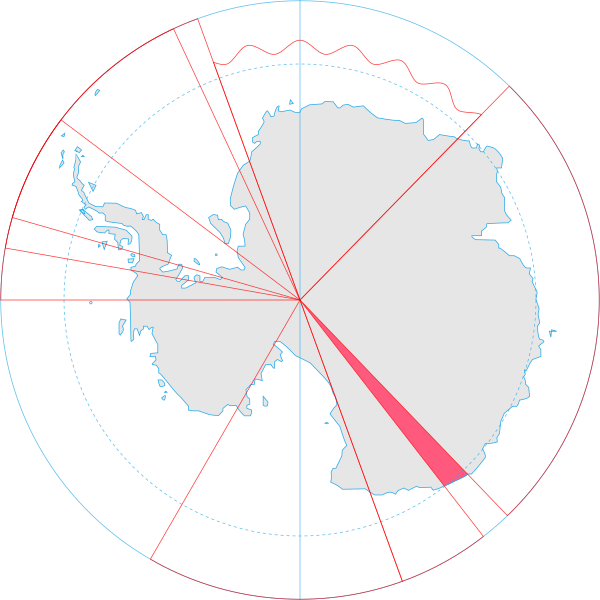

The first notable difference between the United Kingdom and France lies in the size of the claimed lands. Adélie Land, the French-claimed territory is much smaller, around 432 thousand square kilometres, mostly covered by glaciers, and home to two French research facilities. On the contrary, the British Antarctic Territory is more than three times bigger, approximately 1.7 million square kilometres, and, more importantly, overlaps with the claims of Chile and Argentina. There are currently five British, one American, and more than ten Argentinian and Chilean research bases located on its surface.

British Antarctic Territory

The British-claimed area (historically known as the Falkland Islands Dependencies) overlaps significantly with Argentina and Chile’s own claims. Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Adélie Land (French Antarctic Claims)

The 1930 Imperial Conference would see British officials discuss the possibility of attempting to purchase France’s Antarctic claims in exchange for certain islands in the Indian Ocean (which had not been sighted since the 1840s) in an attempt to secure the entire Antarctic for Britain and its Commonwealth. Nothing would come of these ideas, however. Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

The British Antarctic Territory (BAT) also has more “specially protected” (ASPA) and “specially managed” (ASMA) areas that were established and are managed together by the Antarctic Treaty System (ATS) signatories to coordinate the international efforts of scientific research. These territories are governed via jointly drafted and approved management plans. ASPAs and ASMAs, however, are also often viewed as means of asserting territorial claims by showing governance or restricting the presence and influence of other states. As such, given its territorially overlapping claims with Chile and Argentina, it is far from surprising that first, the United Kingdom is the sole proponent of the most, thirteen ASPAs, and second, the BAT is home to the most amount of ASPAs. Due to their geographical closeness, these two Latin American states are also heavily interested in the further exploration and use of this area.

As observed by Hughes and Grant (2017), all ASMAs and ASPAs proposed by any of the states alone with an official claim in Antarctica are located on their claimed territories. In fact, they also tend to be close to these countries’ research stations. This is not different for France or the UK either. However, apart from the aforementioned political means, this might also be due to logistical, financial, and historical reasons. ASMAs or ASPAs far from their claimed land or research bases would require much more time, money, and effort to manage. Nonetheless, it is also suspected that these areas have political value as a result of their potential influence on building construction, transport, safety issues, scientific collaboration, or tourism. Britain, for example, going against the logistical difficulties, advocated for more ASPAs and at a greater distance from its nearest research station.

Competing interests with colonial roots

Both the French and the British claims are protected under the Antarctic Treaty System that – despite multiple efforts of altering it after being signed in 1959 and binding from 1961 – is still in place with all countries wishing to operate in the Antarctic having to adhere to it. The treaty itself, signed by all seven countries with a direct claim and 49 other states, declares that the territory of Antarctica should be used for peaceful purposes only and be free from military and nuclear establishments and activities. From a geopolitical perspective, however, more importantly, it neither bans the use of the military for scientific research nor disapproves of any pre-1959 claims. While it explicitly prohibits any new claims to emerge, it falls short of providing an adequate response to territorial debates such as the one between the UK and the two Latin American states.

As a result, the UK is constantly emphasizing that they were and still are an influential player in the region. Both the British Antarctic Survey (BAS) and the UK Government highlight that Britain has the oldest claim to the land. London, based on its colonizing past, “considers itself rooted” in the Antarctic and seeks to “establish and promote a historical record of [its] presence” and with that “distinguish itself from more recent counterclaimants” (Dodds and Hemmings, 2013). Britain does everything to remain a major power in the continent and retain its influence in the exploration of Antarctica: in some cases, even using its military, it carries out hydrographic surveying, conducts climate research, collects taxes, operates post offices, and oversees tourism.

The reason? Antarctica is a great resource and tourism opportunity. The justification? Britain is the oldest claimant of the land, based on its historic imperial policies (albeit this is disputed by the Latin American countries who date back their claims to the age of the Spanish Empire). This is both ideologically and practically helped by Britain’s internationally acknowledged sovereignty over some sub-Antarctic islands, such as South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands. On the contrary, France, despite also having island dependencies in the region and thus a strategic advantage from a logistics and presence perspective, however, seems to have given up on emphasizing its historical ties to the continent. Adélie Land, which was originally perceived as a contributor to France’s greatness and self-image is now mostly viewed as a territory that’s strategic and political advantages are difficult to measure (Martin-Nielsen, 2021).

Shortcomings and future strategies

Besides preserving the ambiguous status quo, another shortcoming of the Antarctic Treaty is that it does not settle the competing interests in the continent's climate research, fishing, and commercial mining potential either. It was only in 1991 that the Protocol on Environmental Protection to the Antarctic Treaty (also known as the Madrid Protocol) regulated such activities in the Antarctic, which both the UK and France signed. Up to now, most of the Antarctic’s commercial activity has been carried out by either the growing Chinese interest or some western states including the UK and – to a significantly lesser extent – France (Dodds and Hemmings, 2013). In fact, France’s Antarctic logistics was proven to be weak recently, when in 2019 it had to ask for help from Australia to service Adélie Land. This reliance on another state signals France’s declining regional strategical position, as opposed to Britain. Both of them, nonetheless, are said to be concerned about Bejing’s advancing interest.

Beijing becoming increasingly interested in the Antarctica is a strategic question for both France and UK, especially in regard to 2048, when the Antarctic Treaty System is scheduled to be renegotiated through its Environmental Protocol. In fact, the possibility of minerals underneath the Antarctic surface is generating interest from most notably the US, Russia, Japan, and South Africa too. This is why all Antarctic-interested states, including the United Kingdom and France, are trying to enhance their physical presence and scientific activity on the continent; due to the potential that the 2048 renegotiations fall through, or see the ATS shifted towards being more commercially permissive as physical presence and activity, alongside historical legitimacy and geographical defacto authority are key ways in which claims can be made, or preserved (Jardine, 2022).

As for the UK’s aims specifically, they are facilitated by the British Antarctic Survey (BAS), and first and foremost include ensuring the long-term security and environmental protection of its claimed territory. According to a UK Parliament report, the BAS is “integral” to the overall efforts of the UK’s Antarctic foreign policy. More interestingly, however, BAS also sets out the goal of promoting the UK’s sovereignty through among others maintaining an effective legislative and administrative framework and preserving British heritage.

Given the overlap of the British claim with that of Chile and Argentina, this has the potential for political conflicts in the future. France’s aims are equally scientific but less political. As Sulikowski (2013) found, it mainly aims to take up a leading position in Antarctic research and considers the environmental protection of it a globally relevant aim.