Chinese Policy in the Arctic: Iceland

As the smallest Arctic nation, Iceland would be expected to be the least of China’s concerns. Located on the outskirts of the Arctic Circle, despite one hundred percent of its territory considered part of the Arctic, this island nation of roughly 365,000 inhabitants is not one that usually comes to mind when talking about geopolitical rivalry, strategic importance or global influence. Yet its share of China’s interest in the Arctic proves, upon closer examination, quite substantial. Besides the usual culprits of trade routes and natural resources, Iceland has emerged as an important diplomatic and energy partner for China, especially in the past few decades. Having established diplomatic relations with the small state in 1971, China, on the other hand, has since taken care to position itself as a crucial economic partner, as well as a supporting voice for Iceland’s agenda of scientific research and sustainable governance of the Arctic region. The importance of this relationship has recently also come under scrutiny by the United States, which is slowly but surely waking up to its very real security implications. As the global pivot towards China as an important great power continues, and the Arctic grows in prominence, small nations like Iceland are increasingly bound to get caught in the potential geopolitical crossfire.

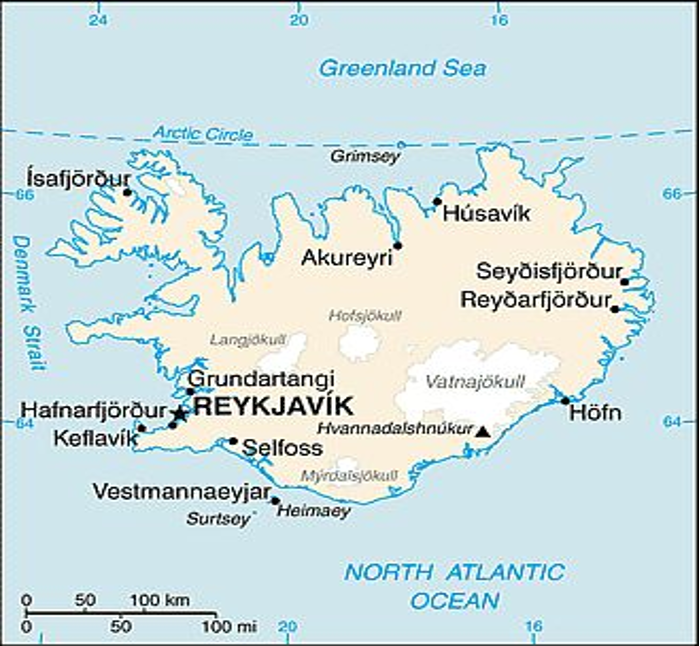

Image 1: Map of Iceland in relation to the Arctic Circle

Emergence of Sino-Icelandic relations - Economy and trade

Despite their 20th century origins, Iceland’s relations with China really only started to take off during the 2008 Global Financial Crisis, which struck hard on the Arctic island. After three of Iceland’s biggest commercial banks collapsed, and its historical go-to allies, the European Union and the United States, found themselves unable to provide the help needed, Iceland turned to China. As it happens, China and Russia were the first countries to offer assistance. However, its relations with the western powers are among the primary reasons for Iceland’s search beyond its geographic neighbours. Soured by complications over fishing quotas during Iceland’s EU membership application process, their relations have continued on a cordial but distant basis, relative to other Arctic nations. Iceland’s economy is heavily reliant on fish products as the primary source of commodity exports (40%), with approximately 4% of the total workforce employed in the fishing industry, and more in other fishing-related activities. Agreeing to strict EU limitations on such activity would thus constitute a hard blow to an already fragile economy. As a result, “China filled the strategic void the EU left behind.” Regarding the US, Iceland has been virtually invisible in American policy since the final withdrawal of US security forces from their first European military base on the island in 2006, at least, until recently. Left to its own devices, Iceland’s turn towards an emerging economic power such as China appears quite understandable.

The first two decades of the 21st century proved fruitful for Sino-Icelandic relations. In 2002, Jiang Zemin became the first Chinese president to visit the island, followed by Iceland’s recognition of China as a fully developed market economy, the first Western European country to do so. Political and diplomatic relations continued to develop apace with economic relations. In 2007, Iceland and China launched negotiations for the latter’s first Free Trade Agreement (FTA) with a European country, which were concluded successfully in 2013. Main areas of cooperation included economic and social development, environmental protection, science and technology, and education. Nevertheless, the majority of Iceland’s imports from China continues to pass through from either the US or the EU. They also continue to dominate Iceland’s export, surpassing China on multiple scores. As researchers from the University of Iceland remark, there are still cultural and value-based barriers between businesses in China and Iceland, which cannot be ameliorated solely through language skill. This can be illustrated by the case of the attempted land purchase by Chinese businessman Huang Nubo in 2011, which was rejected by the Icelandic government. The area, called Grimsstadir, is located in the north of the island, and amounts to approximately 0.3% of its total territory. The purchase was unsuccessful in large part due to concerns over potential dual-use facilities that might have been developed on the territory, and therefore the major security implications that this entailed.

On other grounds, Sino-Icelandic relations, including in the Arctic region, appeared to remain on good terms - in 2012, the Chinese icebreaker Xuelong arrived in Iceland, with the latter’s then-president, Olafur Ragnar Grimsson, becoming the first Head of State to embark the vessel. A year later, Iceland helped China become an observer on the Arctic Council. Even more crucially for their bilateral economic relations, Iceland also participated in the founding of the Arctic Economic Council (AEC), which can provide a potential platform for Chinese investment in the region, although China itself is not a participating member. Nevertheless, Iceland’s key role thus makes the country an even more crucial economic partner for China. Furthermore, Iceland’s chief industry, fishing, is also a source of expanding trade relations, as with many other Arctic countries - Iceland, in fact, exports up to 98% of the seafood it produces. The Bank of Iceland predicted that by 2022 changing Chinese diets would see fish consumption rise to 20.6 kg per person, a figure that proved not far from the truth. China, therefore, can look forward to a steady supply of such products, even as it becomes the 2nd largest importer from Iceland. In the Arctic sphere of relations, China also invited Iceland to become a part of the former’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), which is not a far cry given that Iceland also helped found the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank. As of 2021, however, Iceland’s approval of joining the BRI is still pending. On top of that, Iceland is exploring the potential of turning the country into a logistics hub of the Northern Sea Route (NSR), an ambition that requires port construction, and therefore investment. At the same time, Iceland continues to participate in economic ventures in China, including at the regional level, attending, for example, the Western China International Fair for Investment and Trade (WCIFIT) in Chongqing for the second time in 2022. It appears, therefore, that not even the recent pandemic was able to fully obstruct this growing bilateral relationship.

Productive cooperation - Energy and natural resources

One of the most important sources of cooperation between Iceland and China is also the development of sustainable energy, particularly geothermal energy. Thanks to its natural resources, Iceland is largely self-sufficient in its production and use of energy, the majority (over 85%) of which comes from sustainable, mainly geothermal (66%), sources. Iceland thus finds itself in a good position to help China with its technological expertise in the area, while China is able to serve as the crucial source of funding needed for regular innovation. China, for its part, finds itself increasingly interested in the prospects of geothermal energy exploitation, both domestically and abroad. The reasons are various, not the least of which is the fact that China is home to an estimated one sixth of the world’s geothermal energy reserves. It is no wonder, therefore, that the 13th Five-Year Plan for Economic and Social Development identified the exploration of geothermal resources as a “priority”. As a result, joint geothermal projects are now present in at least 23 cities and counties across the country, and the Icelandic company AGEC currently runs 36 of the geothermal stations present. An example of such joint ventures is the Shaanxi Green Energy Geothermal Development, owned by the Chinese Sinopec (51%) and Icelandic Orka Energy, and funded by a loan from the Asian Development Bank since 2018. With the current cumulative energy potential equivalent to 853 billion tons of coal combustion, Chinese use of geothermal energy has the potential to expand to as much as 25% of the country’s current coal consumption.

Image 2: China’s geothermal energy potential

Abroad, China further pursues cooperation in the exploitation of Icelandic natural resources. Projects include developing Iceland’s oil and gas shelf sites, such as those in the areas of Dreki and Gammur, where the Chinese energy company CNOOC is involved (with a share of 60%). Many are, however, plagued by risky and expensive projections as well as Iceland’s rigorous environmental assessments. Outside of geothermal energy, China is also increasingly interested in Iceland’s wealthy store of mineral and metals. The 2013 FTA includes provisions for greater export of aluminium and, crucially, ferrosilicon, which is an essential element in the production of steel and solar cells.

Image 4: Chinese (CNOOC) and Icelandic (Petoro and Eykon Energy) ownership shares of the Dreki project

Image 3: Dreki and Gammur oil and gas shelves

Multilateral Arctic forums - Diplomatic relations and Arctic governance

Iceland is also very active on matters of Arctic governance, being one of the founding members of the Arctic Council. The country’s Arctic policy states clearly its principal aims of safeguarding the environment of the region, as well as fostering social development and strengthening cooperation. As mentioned before, Iceland pursues these goals largely in multilateral forums for decision-making, while at the same time taking care not to be left behind. When a Danish-led initiative to introduce an ‘Arctic Five’ body took shape, composed of five Arctic states excluding Iceland and Finland, the former took a strong stance against it, announcing that if it was to develop “into a formal platform for regional issues, it can be asserted that solidarity between the eight Arctic States will be dissolved and the Arctic Council considerably weakened.” As a state that is most dependent on Arctic’s varied natural resources, such manoeuvring behaviour is in many ways necessary. Furthermore, it provides a strong case for the importance for a small state of understanding the diplomatic culture and practice in a multilateral organisation. In other words, Iceland’s strength comes from its ability and willingness to cooperate.

Nowhere is this more true than in its own neighbourhood, however, with Greenland, Norway, and Denmark figuring most prominently among its partners for Arctic initiatives. This includes the “most extensive trade agreement ever made”, the Hoyvik FTA between Iceland and the Faroe Islands. When it comes to China, the crucial areas of cooperation remain mostly in the realm of scientific research, the centre of which is the China-Iceland Arctic Observatory (also called Kárhóll), which was opened in 2018. Despite a relative silence in the past couple of years, chiefly the result of the pandemic, Chinese scientists are now beginning to return to the premises to resume the facility’s main objects of study, solar-terrestrial interaction and space weather. It is here, however, that Iceland really begins to receive backlash for its close cooperation with China. As explicitly stated in its Arctic policy documents, Iceland is strictly against any militarisation of the Arctic region. And while the Observatory does not nominally engage in this type of activity, its joint operation with the Polar Research Institute of China has raised more than a few eyebrows. When Iceland began its consideration of joining China’s BRI the same year, it was swiftly brought back into the radar of the United States, which even went as far as to diplomatically nudge Iceland towards a decision, and to thank the nation for declining the offer - despite the fact that Iceland has still not clearly done so.

Conclusion

Whether China’s influence in Iceland creates positive or negative implications in the Arctic region in the long run is in fact still difficult to determine. There is cause for concern, as well as optimism. First and foremost, Iceland’s economic dependence on China is considerable, but should not be exaggerated. Although Iceland attracts the highest levels of Chinese investments as a percentage of its GDP out of all Arctic countries, this investment also remains concentrated in largely niche sectors. Second, although Iceland welcomes cooperation on Arctic governance, including through existing multilateral forums, and is happy to involve China, it is nevertheless not blind to geopolitical and security realities. China does not hold real decision-making power in any of these Arctic forums, and any attempts at militarisation or other ways of compromising Iceland’s or the region’s security are likely to meet with disapproval, loud and clear. As a small nation navigating the relatively uncharted waters of the world’s peripheries, Iceland always makes sure it considers and avoids all potential geopolitical monsters, and ensures, if necessary, that it does not confront them alone.