Eastern Entente: Houthi Campaign

Following developments in the Houthi campaign, the growing cooperation between China, Russia, and Iran is becoming a major concern for the Red Sea region. This emerging ‘Axis’ increases uncertainty for stakeholders in commodity trade, as the stability of the Suez Canal, Strait of Hormuz, and Gulf of Oman are threatened. Iran’s power projection in the region, characterised by the use of proxy groups in an ‘Axis’ of resistance, has paralysed global trade flows. Although China and Russia's involvement is presented as a means to stabilise the region and foster trade, rising scepticism clouds maritime traffic and worsen future prospects (as quantitatively analysed in a recent article by the Global Commodities Watch). The geopolitical and economic implications are profound and pose risks to all parties involved, raising questions about the motives behind this new ‘Axis’ formation and what it means for the disruptive ‘Axis of Resistance’.

Axis of Resistance - In Retrospect

Since the Iranian Revolution of 1979, the Tehran regime’s foreign policy has been characterised by its desire to propagate its brand of Shi’a Islam across the Middle East. To this end, it has long developed and fostered relationships with sympathetic proxy groups throughout the region. This has allowed it to project power in locations that might otherwise be beyond its reach while exercising some degree of “plausible deniability." In January 2022, this prompted the former Israeli Prime Minister, Naftali Bennett, to brand Iran “an octopus” of terror whose tentacles spread across the Middle East.

The country’s so-called “Axis of Resistance'' has expanded since 1979, its first major franchise being Hezbollah, which was founded in 1982 to counter Israel’s invasion of Lebanon that year. Its most recent recruit has been the Houthis. This group was established in northern Yemen in the 1980s to defend the rights of the country’s Shi’a Zaidi minority. What was initially a politico-religious organisation then evolved into an armed group that fought the government for greater freedoms. It was able to exploit the chaos of the Arab Spring to capture the national capital, Sana’a, in the autumn of 2014, and the group now controls around 80% of Yemen’s population.

Exactly when the Houthis became a part of the “Axis of Resistance” is something of a moot point, but the general consensus among the group’s observers is that it started receiving Iranian military assistance around 2009, with this almost certainly contributing to its capture of the Yemeni capital, Sana’a, in 2014. Since the HAMAS attack against Israel on October 7, 2023, it has rapidly emerged as a key Iranian franchise whose focus has been attacking shipping in the southern Red Sea. At the time of writing, an excess of 40 vessels had been targeted, while repeated US-led strikes against Houthi military infrastructure on the Yemeni coast appeared to have had limited success in degrading the group’s intent or capability.

March 2024 saw a proliferation in the number and efficacy of attacks, with the first three fatalities reported on the sixth of the month as the Barbados-flagged bulk carrier True Confidence was struck near the coast of Yemen. Around three weeks later, on March 26th, four ships were attacked with six drones or missiles in a single 72-hour period. Separately, on March 17th, what is believed to have been a Houthi cruise missile breached southern Israel’s air defences, coming down somewhere north of Eilat, albeit harmlessly.

Since starting their campaign against mainly international commercial shipping in the waters of the Red Sea and Gulf of Aden in November 2023, the Houthis have become one of the mostaggressive Iranian proxy groups in the Middle East. This and their apparently strengthened resolve in the face of US and UK strikes have substantially raised their profile internationally and won them plentifulplauditsfrom their supporters across the region. The perception that they are standing up to the US, Israel, and their Western cohorts has been instrumental in developing their motto“God is great, death to the U.S., death to Israel, curse the Jews, and victory for Islam” into a mission statement.

Map of Houthi Attacks

Source: BBC

Iran-Houthi Mutualism

In terms of regional geopolitics, the mutual benefits to Iran and the Houthis of their cooperation are far-reaching. For their part, the Iranians can use the Houthis to project power west into the Red Sea and Gulf of Aden, pushing back against the influence of Saudi Arabia and other Sunni states. Although not part of the Abrahamic Accords of 2020, Riyadh has been showing signs of a willingness to harmonise diplomatic relations with Israel, even since the events following October 7, 2023. This is a complete anathema to Tehran, for which the Palestinian cause is central to its historic antagonism with Tel Aviv. The fact that Saudi Arabia was instrumental in setting up the coalition of nine countries that intervened against the Houthis in Yemen from 2015 onwards only strengthens Tehran’s desire to confront the country’s influence regionally.

A secondary benefit of the Houthis’ Red Sea campaign is that it helps to maintain Tehran’s maritime supply lines to some of its franchise groups further north in Lebanon, Gaza, and Syria. Their importance to Iran’s proxy operations was illustrated in March 2014 when the Israel Defence Forces (IDF) conducted “Operation Discovery," intercepting a cargo ship bound for Port Sudan on the Red Sea’s western shores carrying a large number of M-302 long-range rockets. Originating in Syria, they were reckoned to have been destined for HAMAS in Gaza following a circuitous route that included Iran and Iraq and which would have culminated in a land journey from Port Sudan north through Egypt to the Levant.

Iran began to increase its military presence in the Red Sea in February 2011 and has since established a near-permanent presence there and in the Gulf of Aden, to the south, with both surface vessels and submarines. However, this footprint is relatively weak compared to that of its presence in the Persian Gulf, to the east, and it would be no match for the Western vessels that have been operating against the Houthis in the Red Sea since late 2023. The latter’s campaign in these waters can, therefore, only reinforce Iran’s presence thereabouts.

A lesser-known reason for Iran’s desire to maintain influence around the Red Sea is a small archipelago of four islands strategically located on the eastern approaches to the Gulf of Aden from the Indian Ocean and Arabian Sea. The largest of the four islands is called Socotra and is considered by some to have been the location of the Garden of Eden. With a surface area of a little over 1,400 square miles, it has, in recent years, found itself more and more embroiled in the struggle for hegemony between Iran and its Sunni opponents in the region. In this sense, it and its neighbours could be seen to have an equivalence to some of the small islands and atolls of the South China Sea that are now finding themselves increasingly on the frontlines of Beijing’s regional expansionism.

While officially Yemeni, Socotra has long enjoyed close ties with the United Arab Emirates (UAE), with approximately 30% of the island’s population residing in the latter. Following a series of very damaging extreme weather events in 2015 and 2018, the UAE strengthened its hold on Socotra by providing much-needed aid, with military units arriving entirely unannounced in April 2018. Vocal opposition from the Saudi-allied Yemeni government led to Riyadh deploying its own forces to the island in the same year, but these were forced to withdraw in 2020 when the UAE-allied Southern Transition Council (STC) took full control of the island. Since then, Socotra has been considered to be a de facto UAE protectorate, extending the latter’s own influence south into the Gulf of Aden.

Shortly after came the signing of the Abrahamic Accords, which normalised relations between Israel and several other regional countries, including the UAE. Enhanced cooperation with the UAE gave Tel Aviv a unique opportunity to expand its own influence in the region through military cooperation with its new ally. In the summer of 2022, it was reported that some inhabitants of the small island of Abd al-Kuri, 130 km west of Socotra, had been forced from their homes to make way for what has been described as a joint UAE-Israeli “spy base." For Iran, this means that Israel now has a presence at a strategic point on the strategically vital approaches to the Red Sea from the Indian Ocean.

Perhaps a greater irritant for both the Houthis and Iran is the presence of UAE forces on the small island of Perim. This sits just 3 km from the Yemeni coast in the eastern portion of the Bab al-Mandab Strait, giving it obvious strategic importance. The UAE took the island from Houthi forces in 2015 and started to construct an airbase there almost immediately. Although there is no known Israeli presence there, Perim is now a major thorn in the side of Iran’s own regional ambitions. In the regional tussle for supremacy, this is yet another very pragmatic reason for the Houthi-Iran relationship.

Perim Airbase

Source: The Guardian

Since February 2022, much has been made of the extent to which Ukraine has become a weapons incubator for both sides in the conflict there, not least with regard to innovative drone and AI technology. Given the range of weaponry now apparently at the disposal of the Houthis in the Red Sea and Gulf of Aden, it may be that that campaign is serving a similar purpose for a Tehran keen to test recent additions to its armoury. Indeed, the Houthis’ use of a range of modern weapons, including drones, Unmanned Underwater Vehicles, and cruise missiles, since November 2023 continues to be reported on a regular basis.

In return for prosecuting its campaign in the Red Sea, the latter received substantial material military support from Tehran, allowing them to raise their standing even more. The aforementioned attack, which killed three seafarers aboard the True Confidence, was the first effective strike against a ship using an Anti-Ship ballistic Missile (ASBM) in the history of naval warfare. First and foremost, this will have been regarded as a major coup for the Iranian military assets mentoring the Houthis in Yemen. Additionally, it has given the latter’s global standing a further boost since an attack of this magnitude would be more normally associated with the much more sophisticated standing military of a larger country.

A simplistic analysis of the Houthi-Iranian relationship could stop at this point. However, recent events in the Middle East and further afield show that it is a relatively small coupling in a much larger, global marriage of convenience. A clue to this appeared in media reporting in late January 2024, when The Voice of America reported that Korean Hangul characters had been found on the remains of at least one missile fired by the Houthis. This led to the conclusion that the Yemeni group has received North Korean equipment via Iran.

North Korean missile supposedly used by the Houthis

Source: VOA

Russian Involvement

In late March 2024, Russia and China signed a historic pact with the Houthi in which the nations obtained assurance of safe passage through the Red Sea and Gulf of Aden in return for ‘political support’ to the Shia militant group. Despite the assurance, safety for Russian and Chinese vessels is not guaranteed. In late January, explosions from missiles were recorded just one nautical mile from a Russian vessel shipping oil, while on the 23rd of April, four missiles were launched in the proximity of the Chinese-owned oil tanker Huang Lu. Evidently, increased regional tensions incur an extra security risk for Russian tankers, regardless of the will of the Houthis to keep said tankers safe.

The Kremlin is trying to walk a thin line between provoking and destabilising the West while simultaneously trying to avoid, literally and figuratively, capsizing regional Russian maritime activity. Its seemingly contradictory two-pronged approach aims to secure vital shipping routes while fostering an anti-Western bond with regional actors. Russia is seen upholding its anti-West rhetoric, which serves as a cornerstone for bonding with regional actors and pushing forth Russian economic interests, while silently attempting to facilitate regional de-escalation led by Washington. Despite being a heavy user of their veto power in the UNSC, Russia abstained from voting on Resolution 2722, which demands the Houthis immediately stop attacks on merchant and commercial vessels in the Red Sea.

On January 11th, Washington put forth UN Resolution 2722 to the UNSC, which sought to justify attacks on Houthi infrastructure as a push-back for the group’s recent activities in the Red Sea. During the voting procedure of the resolution, Russia chose to abstain, even though Moscow often frequents vetoes as a tactic to show support for Kremlin-friendly states in Africa and the Middle East. The resolution subsequently passed, and the US and UK commenced their first strikes on Yemen the following day. These reveal Russia’s interests in securing enough stability to continue shipping its estimated 3 million barrels of oil a day to India, while aligning with overarching geopolitical alignments.

Russia’s interest in stabilising regional conflicts may lie in the threats to its weapon supply chains. As the war in Ukraine drags on, Tehran’s importance as a weapon supplier increases the Kremlin’s collaboration efforts. Putin continues to foster and protect regional connections by actively protesting Western regional presence, attempting to balance the current crisis with crucial ties to middle-eastern nations.

Trade Route Diversion

Since the onset of the crisis in the strait, Russia has utilised the opportunity to bolster anti-Western and pro-Russian sentiments. For one, Russia has flagged various Russian transport initiatives. On January 29th, Russia’s Deputy Prime Minister, Alexey Overchuk, noted that Russia’s “main focus is on the development of the North-South international transportation corridor," which is a 7200-km multi-modal transport network offering an alternative and shorter trade route between Northern Europe and South Asia.

International North-South Trade Corridor

A key part of the trade route involves an imagined rail network spanning from Russia to Iran. Though positioned as a universally beneficial transport option for both Europe and Asia, it seems Moscow and Tehran would benefit the most. The two highly sanctioned states, whose connection has recently deepened due to their shared economic isolation from the global economy, could position themselves as lynchpins of an effective transport network.

Unlike Tehran, which still has control over the vital Strait of Hormuz choke point, Russia’s political might in terms of energy transport networks is quickly dwindling after the Baltic states’ complete exit from the BRELL energy system and the West’s resolve to decrease energy dependence. The North-South corridor thereby holds value as a catalyst of global energy transport and trade.

However, this vision is thwarted by financial crises, with workon the railroad from Rasht to Astara in Iran suffering setbacks. Iran does not have the means to pour into the project and has already obtained a 500 million euro loan (about half of the total cost of construction) from Azerbaijan in FDI. In May 2023, it became known that the Kremlin would fund the project themselves by issuing a 1.3 billion euro loan to Tehran, despite Iran’s ballooning debt to Russia. The same month, Marat Khusnullin, Deputy Prime Minister, announced that Russia is expecting to invest approximately $3.5 billion in the North-South corridor by 2030. This is likely a major underestimation of the costs needed to complete the project.

With Iran’s growing debt and Russia’s war-born financial strain, further trade route developments are sure to be delayed. Seeing as the railroad project between Russia, Azerbaijan, and Iran has been in existence since 2005 with no concrete end in sight, the North-South Corridor, despite Russia’s active marketing campaign in light of the troubles in the Red Sea, is unlikely to become a viable transport option in the near future.

The Northern Sea Route (NSR), which Putin has similarly promoted since the start of the Houthi attacks, is likely to suffer a similar fate. The NSR’s realisation as a major global route is hindered by the fact that the Arctic Circle’s harsh climate causes the route to be icebound for about half of the year. Furthermore, in light of the recent war in Ukraine, the NSR is off-limits to even being considered a viable transportation route for large swaths of the West due to sanctions against Putin’s regime.

Russia: Long-Term Strategy

With Russia’s closest regional naval presence being Tartus in Syria, Russia is also interested in establishing naval bases closer to the Red Sea. Russia’s primary interest is to establish a port in Sudan. High-level bilateral negotiations have been actively taking place between Khartoum and Moscow, with an official deal being announced in late 2020. The construction of a naval base would increase Russia’s influence over Africa, facilitating power projection in the Indian Ocean. Nonetheless, the ongoing Sudanese civil war seems to have stalled negotiations.

The region is of such strategic interest to Russia that Moscow has recently pushed forth another alternative for bolstering its presence in the Red Sea: a naval base in Eritrea. During a state visit to Eritrea in 2023, Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov underscored the potential that the Massawa port holds. The same year, a Memorandum of Understanding was signed between the city of Massawa and the Russian Black Sea naval base Sevastopol, in which the two countries pledged to foster closer ties in the future.

A New Axis

China and Russia have recently struck a deal with the Houthis to ensure ship safety, as reported by a Bloomberg article. Under the agreement, ships from China and Russia are permitted to sail through the Red Sea and the Suez Canal without fear of attack. In return, both countries have agreed to offer some form of “political support” to the Houthis. Although the exact nature of this support remains unclear, one potential manifestation could involve backing the Yemeni militant group in international institutions such as the United Nations Security Council. In January 2024, a resolution condemning attacks carried out by the Houthi rebels off the coast of Yemen was passed, with China and Russia among the four countries that abstained.

Despite instances of misfiring by Chinese ships after the deal, the alignment between these countries has been viewed as the emergence of an “axis of evil 2.0." Coined by former U.S. President George W. Bush at the start of the war on terror in 2002, the term “axis of evil” originally referred to Iran, Iraq, and North Korea, which were accused of sponsoring terrorism by U.S. politicians. Indeed, China and Iran have maintained a robust economic and diplomatic relationship. China is a significant buyer of Iranian oil, purchasing around 90 percent of Iran’s oil output, totalling 1.2 million barrels a day since the beginning of 2023, as the U.S. continues to enforce Iranian oil sanctions.

Chinese Dominance of Iranian Crude Oil Exports

Source: Seeking Alpha

However, it may be far-fetched to consider China, Russia, Iran, and North Korea as a united force akin to the Communist bloc against the West during the Cold War. After all, there are significant tensions within these relationships. For example, Beijing has not fully aligned with Moscow regarding the invasion of Ukraine. Additionally, there are power imbalances within these relationships, as Iran relies on China far more than China relies on Iran.

Despite the thinness of this idea of an "axis," it remains concerning that these powerful countries (three of which are nuclear-armed) are aligning against the democratic world. Considering the volume of trade passing through the Suez Canal and the impossibility for the U.S. and company’s Operation Prosperity Guardian to protect every ship in the region, the deal struck between China, Russia, and Iran may be a significant factor that could shift the current global economic balance towards the side of the "Eastern Axis.”

Similarly, China’s recent activities against the Philippines in the South China Sea could be viewed as an attempt to undermine the Philippines’ economy, which heavily relies on its seaports. This could force the Philippines to capitulate or incur significant costs for the U.S. should it decide to provide more assistance to further enhance the Philippines’ defence capabilities.

China: Long-Term Strategy

In recent years, China has increased its ties with countries outside the ‘Western sphere’. Apart from being present in the Gulf of Oman and destining a myriad of vessels to secure the region, it has made strides in developing long-term partnerships with Russia and Iran. Chinese collaboration with Russia is advertised as having “no limits,”, and its 25-Year Comprehensive Cooperation Agreement with Iran further cements its political and economic involvement with both nations.

The security and economic aspects of China’s long-term plans are the most relevant to commodity trade, as violent conflicts and geopolitical tensions are the prime hindrances to trade flows through the region. Nonetheless, the cooperation of these nations does not bode well with the West and could negatively impact trade regardless of improved security.

China’s circumvention of the financial sanctions placed on Iran mocks the international community’s concerted effort to dissuade Tehran’s human rights violations, nuclear activities, and involvement in the Russia-Ukraine war. Its “teapot” strategy, which allowed China to purchase90% of total Iranian oil exports, relies on the use of dark fleet tankers and small refineries to avoid detection and evade the financial sanctions placed on Iranian exports.

Increased its bilateral trade flows with Russia also point to increased cooperation, with $88 billion worth of energy commodities being imported by China in 2022, with imports of natural gas increasing by 50% and crude oil by 10%, reaching 80 million metric tonnes. In 2023, bilateral trade reached $240 billion, proving both countries hold cooperation as a pillar of their economic strategy.

Chinese-Iranian Oil Trade

Source: Nikkei Asia

The West has increased efforts to dissuade cooperation with Russia, as seen with the creation of the secondary sanction authority. These sanctions cut off financial institutions that transact with Russia’s military complex from the U.S. financial system and have successfully led three of the largest Chinese banks to cease transactions with sanctioned companies. Despite the success of certain measures and sanctions, cooperation between both states remains, and their involvement in the Middle East will ensure collaborative efforts for the foreseeable future.

Conclusion

The evident development of collaborative endeavours among the ‘Eastern Axis’ countries is enough to engender strife and uncertainty in trade in the Red Sea. It is becoming increasingly evident that uncertainty will still roam the seas regardless of whether the Houthi conflict is tamed, preventing maritime trade in the Red Sea’s key routes from reaching their potential. The reliance of regional security on both violent attacks and political alignments, such as the involvement of the Eastern Axis in the region, highlights how deeply supply-chain stability is intertwined with geopolitical relations, establishing Iran as a determinant of the Red Sea’s future commodity trade prosperity.

A Strait Betwixt Two

As the Yemeni Houthi group's assault on maritime vessels continues to escalate, the risk to key commodity supply chains raises global concern. As analysed in this series' previous article (available here), conflict escalation impacts the region's security, impacting key trade routes and global trade patterns. The Suez Canal is a key trade route whose stability and security could impact and shift trade dynamics. As the search for alternative trade routes ensues, the Strait of Hormuz makes use of a power vacuum to expand its influence.

Suez Canal

The Suez Canal is a 193-kilometre waterway that connects the Red Sea to the Mediterranean Sea. Approximately 12% of global trade passes through the Canal, granting it vast economic, strategic, and geopolitical influence on a global scale. This canal shortens maritime trade routes between Asia and Europe by approximately 6,000 km by removing the need to export around the Cape of Good Hope and serves as a vital passage for oil shipments from the Persian Gulf to the West. Approximately 5.5 million barrels of oil a day pass through the Canal, making it a ‘competitor’ of the Strait of Hormuz.

Global trade via the Suez Canal is likely to decrease as a result of the rising tensions near the Bab el-Mandeb Strait. Due to their geographic predispositions, the Bab el-Mandeb Strait and the Suez Canal are interdependent; bottlenecks in either trade choke point will have a knock-on effect on the other. Bottlenecks caused by Houthi aggression against ships in the strait are likely to redirect maritime traffic from the Suez Canal to alternative passageways. From November to December 2023, the volume of shipping containers that passed through the Canal decreased from 500,000 to 200,000 per day, respectively, representing a reduction of 60%.

Suez Canal Trade Volume Differences (metric tonnes)

The overall trade volume in the Suez Canal has decreased drastically. Between October 7th, 2023, and February 25th, 2024, the channel’s trade volume decreased from 5,265,473 metric tonnes to 2,018,974 metric tonnes. As the weaponization of supply chains becomes part of regional economic power plays, there is a global interest in decreasing the vulnerability of vital choke points via trade route diversification. The lack of transport routes connecting Europe and Asia has hampered these interests, making choke points increasingly susceptible to exploitation.

Oil Trade Volumes in Millions of Barrels per Day in Vital Global Chokepoints

Source: Reuters

Quantitative Analysis

Many cargoes have been rerouted through the Cape of Good Hope to avoid the Red Sea region since the beginning of the Houthi conflict. Several European automakers announced reductions in operations due to delays in auto parts produced in Asia, demonstrating the high exposure of sectors dependent on imports from China.

In the first two weeks of 2024, cargo traffic decreased by 30% and tanker oil carriers by 19%. In contrast, transit around the Cape of Good Hope increased by 66% with cargoes and 65% by tankers in the same period. According to the analysis of JP Morgan economists, rerouting will increase transit times by 30% and reduce shipping capacities by 9%.

Depiction of Trade Route Diversion

Source: Al Jazeera

More fuel is used in the rerouted freight, an additional cost that increases the risk of cargo seizure and results in elevated shipping rates. The most affected routes were from Asia towards Europe, with 40% of their bilateral trade traversing the Red Sea. The freight rates of the north of Europe until the Far East, utilising the large ports of China and Singapore, have increased by 235% since mid-December; freights to the Mediterranean countries increased by 243%. Freights of products from China to the US spiked 140% two months into the conflict, from November 2023 to January 25, 2024. The OECD estimates that if the doubling of freight persists for a year, global inflation might rise to 0.4%.

The upward trend in freight rates can be seen in the graphic pictured below, depicting the “Shanghai Containerised Freight Index” (SCFI). The index represents the cost increase in times of crisis, such as at the beginning of the pandemic, when there were shipping and productive constraints, and more recently, with the Houthi rebel attacks. Most shipments through the Red Sea are container goods, accounting for 30% of the total global trade. Companies such as IKEA, Amazon, and Walmart use this route to deliver their Asian-made goods. As large corporations fear logistic and supply chain risk, more crucial trade volumes could be rerouted.

Shanghai Containerized Freight Index

Energy Commodity Impact

Of the commodities that traverse the Red Sea, oil and gas appear to be the most vulnerable. Before the attacks, 12% of the oil trade transited through the Red Sea, with a daily average of 8.2 million barrels. Most of this crude oil comes from the Middle East, destined for European markets, or from Russia, which sends 80% of its total oil exports to Chinese and Indian markets. The amount of oil from the Middle East remained robust in January. Saudi oil is being shipped from Muajjiz (already in the Red Sea) in order to avoid attack-hotspots in the strait of Bab al-Mandeb.

Iraq has been more cautious, contouring the Cape of Good Hope and increasing delays on its cargo. Iraq's oil imports to the region reached 500 thousand barrels per day (kbd) in February, 55% less than the previous year's daily average. Conversely, Iraq's oil imports increased in Asia, signalling a potential reshuffling of transport destinations. Trade with India reached a new high since April 2022 of 1.15 million barrels per day (mbd) in January 2024, a 26% increase from the daily average imports from Iraq's crude.

Brent Crude and WTI Crude Fluctuations

Source: Technopedia

Refined products were also impacted. Usually, 3.5 MBd were shipped via the Suez Canal in 2023, or around 14% of the total global flow. Nearly 15% of the global trade in Naphta passes through the Red Sea, amounting to 450 kbd. One of these cargoes was attacked, the Martin Luanda, laden with Russian naphtha, causing a 130 kbd reduction in January compared with the same month in 2023. Traffic to and from Europe is being diverted in light of the conflict. Jet fuel cargoes sent from India and the Middle East to Europe, amounting to 480 kbd, are avoiding the affected region, circling the Cape of Good Hope.

Due to these extra miles and higher speeds to counteract the delays, bunker fuel sales saw record highs in Singapore and the Middle East. The vessel must use more fuel, and bunker fuel demand increased by 12.1% in a year-over-year comparison in Singapore.

In 2023, eight percent, or 31.7 billion cubic metres (bcm), of the LNG trade traversed the Red Sea. The US and Qatar exports are the most prominent in the Red Sea. After sanctioning Russia's oil because of the Ukrainian War, Europe started to rely more on LNG shipments from the Middle East, mainly from Qatar. The country shipped 15 metric tonnes of LNG via the Red Sea to Europe, representing a share of 19% of the Qatari LNG exports. Vessels travelling to and from Qatar will have to circle the Cape of Good Hope, adding 10–11 days to travel times and negatively impacting cargo transit.

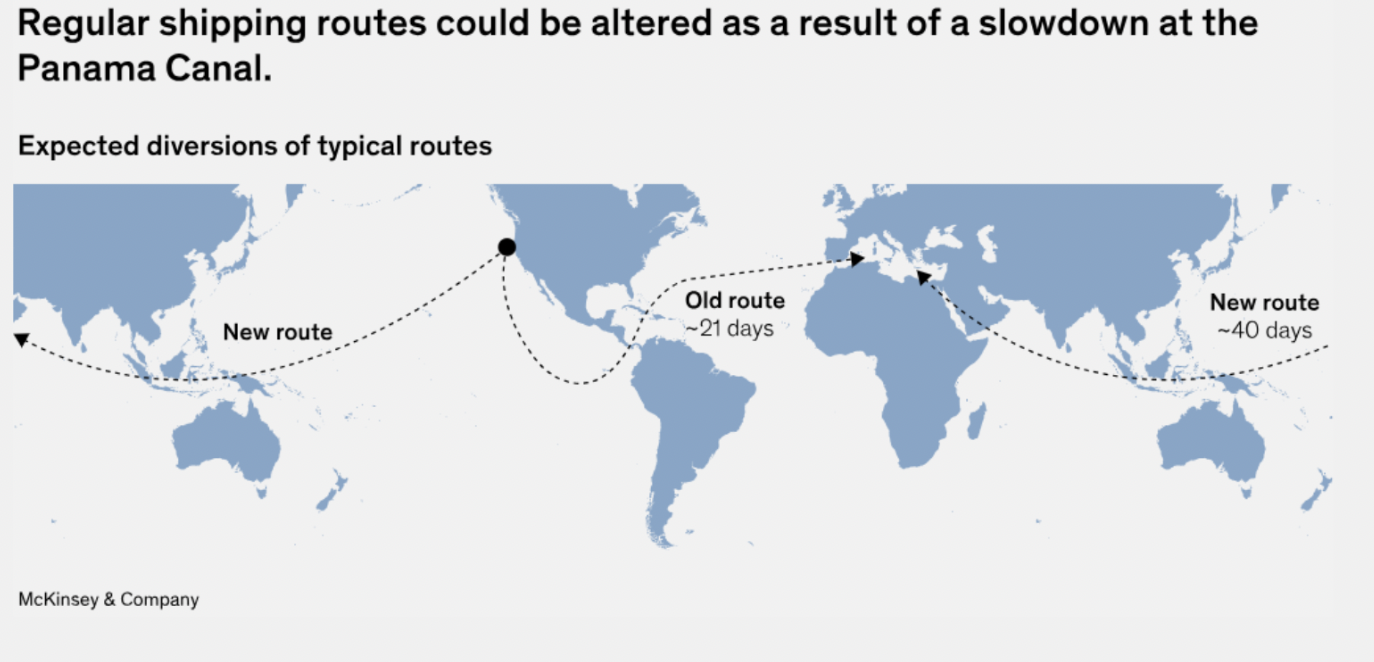

US LNG export capacity has increased in the past few years, sending shipments to Asia via the Red Sea. The Panama Canal receives many LNG cargoes from the US via the Pacific, yet its traffic limitations cause US cargo to be routed through the Atlantic and the Red Sea. The figure “Trade Shipping Routes” below displays the dimensions of the shifts that US LNG cargoes must take in the absence of passage via the Panama Canal.

Trade Shipping Routes

Source: McKinsey & Company

Until January 15, at least 30 LNG tankers were rerouted to pass through the Cape of Good Hope instead. Russia's LNG shipments to Asia are currently avoiding the Red Sea, and Qatar did not send any new shipments in the last fortnight of January after the Western strikes at Houthi targets.

Risk Assessment

A share of 12% of oil tankers, ships designed to carry oil, and 8% of liquified gas pass through this route towards the Mediterranean. Inventories in Europe are still high, but if the crisis persists for several months, energy prices could be aggravated. As evidenced by the sanctions against Russia, cargo reshuffling is possible. Qatar can send its cargoes to Asia, and those from the US can go to European markets, allowing suppliers to effectively avoid the Red Sea.

Around 12% of the seaborn grains traversed the Red Sea, representing monthly grain shipments of 7 megatonnes. The most considerable bulk are wheat and grain exports from the US, Europe, and the Black Sea. Around 4.5 million metric tonnes of grain shipments from December to February avoided the area, with a notable decrease of 40% in wheat exports. The attacks affected Robusta coffee cargoes as well. Cargoes from Vietnam, Indonesia, and India towards Europe were intercepted, impacting shipping prices and incentivizing trade with alternative nations.

Daily arrivals of bulk dry vessels, including iron ore and grain from Asia, were down by 45% on January 28, 2024, and container goods were down by 91%. However, further significant disruptions to agricultural exports are not expected. Most of the exports from the US, a large bulk, were passing through the Suez Canal to avoid the congestion of the Panama Canal due to the droughts that limited the capacity of circulation. These cargoes are now traversing the Cape route.

Around 320 million metric tonnes of bulk sail through Suez, or 7% of the world bulk trade. No significant impacts are predicted for iron ore or coal, which represented 42 and 99 megatonnes of volume, respectively, shipped through the Red Sea in 2023. Most of the dry bulks that traverse the impacted region can be purchased from other suppliers, precluding significant supply disruptions.

As of March 1st, reports show that only grain shipments and Iranian vessels were passing through the Red Sea. There were no oil or LNG shipments with non-Iranian links in the Red Sea. These developments illustrate the significant trade shifts caused by the Red Sea crisis. As of today, a looming threat lies in the Houthis’ promises of large-scale attacks during Ramadan. The lack of intelligence on the Houthi’s military capacity and power makes it difficult to ascertain the extent of future conflicts, generating further uncertainty in commercial trade.

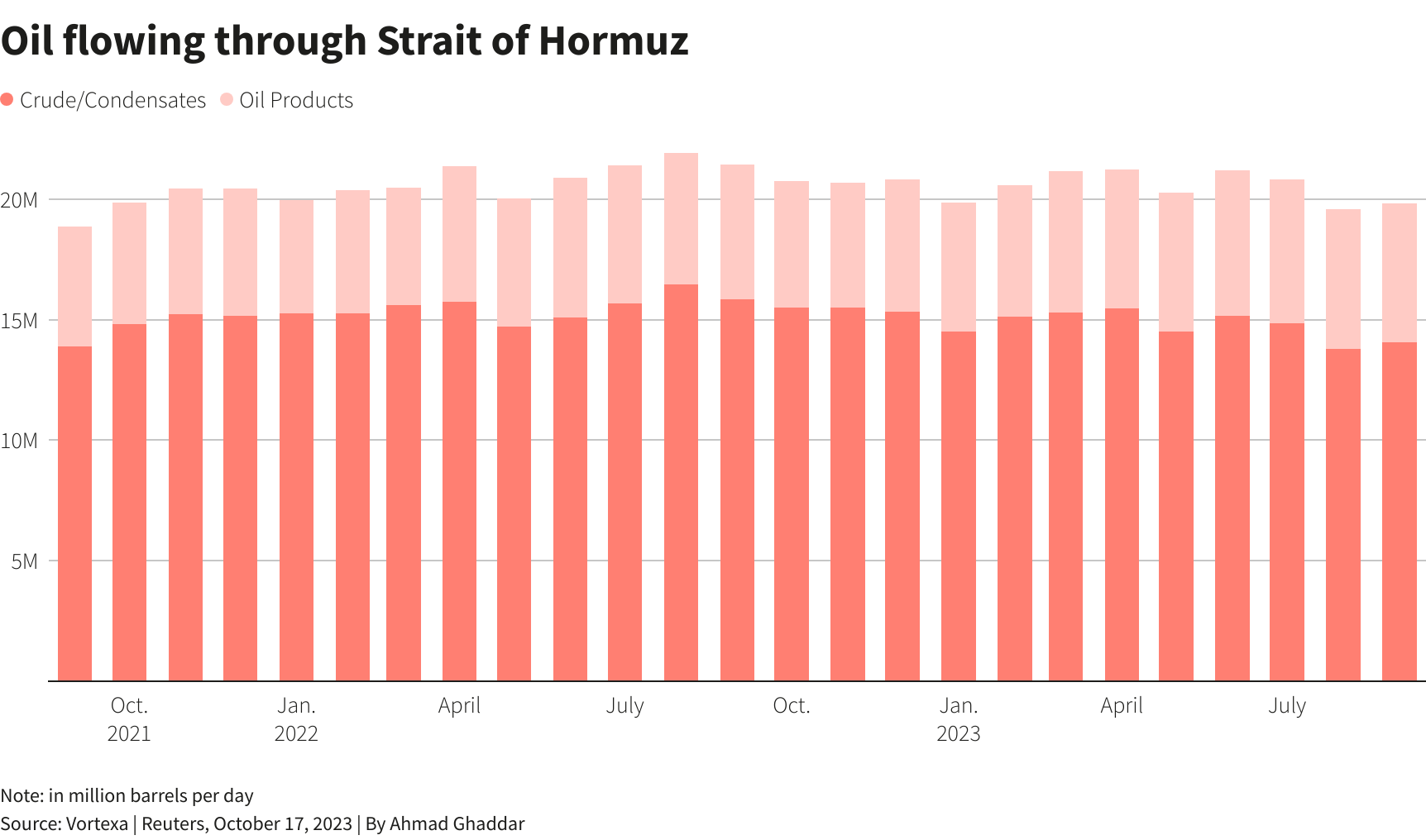

The Strait of Hormuz

The Strait of Hormuz is a channel that connects the Persian Gulf to the Gulf of Oman, providing Iran, Oman, and the UAE with access to maritime traffic and trade. The strait is estimated to carry about one-fifth of the global oil at a daily trade volume of 20.5 million barrels, proving to be of vital strategic importance for Middle Eastern oil supply the world’s largest oil transit chokepoint. The strait is a prominent trade corridor for a myriad of oil-exporting nations, namely the OPEC members Saudi Arabia, Iran, the UAE, Kuwait, and Iraq. These nations export most of their crude oil via the passage, with total volumes reaching 21 mb of crude oil daily, or 21% of total petroleum liquid products. Additionally, Qatar, the largest global exporter of LNG, exports most of its LNG via the Strait.

Geographic Location of Strait of Hormuz

Source: Marketwatch

Although the strait is technically regulated by the 1982 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, Iran has not ratified the agreement. Through its geostrategic placement, Iran can trigger oil price responses through its influence on trade transit, establishing the country’s regional and global influence.

Strait of Hormuz Oil Volumes

Source: Reuters

Experts are particularly worried that the turbulence is likely to spread to the Strait of Hormuz now that Iran backs the Houthis in Yemen and might want to support their cause by doubling down regionally. However, this is something that would cause a lot of backlash in the form of a further tightening of economic sanctions against Tehran, which might deter further provocations.

Despite Iran’s previous threats to block the Strait entirely, these have never gone into effect. Diversifying trade routes to avoid supply shocks and bottlenecks is of interest to regional oil-exporters dependent on the route for maritime trade access. Such diversification attempts have already been undertaken, as seen by the UAE and Saudi Arabia's attempts to bypass the Strait of Hormuz through the construction of alternative oil pipelines. The loss of trade volume from these two producers, holding the world's second and fifth largest oil reserves, respectively, severely hindered the corridor’s prominence.

The attacks on the Red Sea might cause damage to the oil and LNG cargo from countries in the Persian Gulf, increasing costs for oil and gas exporters. However, cargoes could find alternative destinations. The vast Asian markets, which face a shortage of energy products due to a loss of trade through the Red Sea, could be a potential suitor. Finding new LPG (liquefied petroleum gas) contracts could be beneficial for Iran, and its recently enhanced production capacity could supply various markets.

Geopolitics and Prospects for a Route Shift

Although the Strait of Hormuz stands to capture diverted trade flows from the Suez Canal, its global influence is still limited by Iran’s geopolitical ties. As exemplified by the Iran-US conflict, Iran’s conflicts can severely impact traffic through the Strait, significantly impacting the stability of the route and prospects for future growth.

Although security and stability are of paramount importance to trade, efforts to provide these traits could be counterproductive. On March 12th, China and Russia conducted maritime drills and exercises in the Gulf of Oman with naval and aviation vessels. According to Russia's Ministry of Defence, this five-day exercise sought to enhance the security of maritime economic activities using maritime vessels with anti-ship missiles and advanced defence systems. Over 20 vessels were displayed in this joint naval drill, attempting to lure trade through the promise of stability and security.

Whether meant as a display of power or a promise of security, the pronounced presence of Russian and Chinese forces could aggravate geopolitical tensions and increase the potential for conflict in the region, driving global trade prospects down. With precedents of trade conflict, such as the IRGC’s seizure of an American oil cargo in the Persian Gulf on January 22nd, various countries might be sceptical of rerouting commodity trade through the Strait.

Tensions are also aggravated by Iran’s alleged assistance in the Houthi attacks. The US has supposedly communicated indirectly with Iran to urge them to intervene in the region. China and Russia’s interest in improving the Strait’s trade prospects would benefit from a de-escalation of the Houthi conflict, as shown by China’s insistence on Iran’s cooperation in the Houthi conflict. As the conflict stands, the Strait’s prospect as an alternative trade route is dependent not only on Iran’s reputation and presence in global conflicts but also on the route’s patrons and proponents.

Conclusion

The extent to which the Strait of Hormuz could benefit from trade diversion depends not only on its ability to pose itself as a viable trade route but also on the duration of the Houthi conflict. In order to capture trade volumes and increase international trade through the route, Iran would have to ameliorate its geopolitical ties and provide stability to compete with rising prospective trade route alternatives. Although the conflict in the Suez has yet to show promising signs of de-escalation, securing the Suez would likely cause previous trade volumes to resume and restore its hegemony in commodity trade. It remains to be seen whether the conflict will endure long enough to allow other trade routes to be established as alternatives and permanently shift power balances in global trade.

The Houthi Campaign in the Red Sea and Gulf of Aden - An Update

Key Findings

There are currently no indications that either the US or Iran’s “Axis of Resistance” have an appetite for wider conflict in the Middle East

The 13-week old Houthi campaign against international shipping in the Red Sea and Gulf of Aden shows no signs of abating

The Houthis are probably capable of conducting more damaging strikes than have been reported hitherto, but are acting with restraint for the moment

If even a measured attack against a commercial or military vessel were to cause significant casualties, this could lead to an escalation

The forthcoming holy month of Ramadan is not likely to precipitate an increase in Houthi attacks

Background - The Story So Far

Since 19th November 2023, at least 38 mainly commercial vessels transiting the Gulf of Aden and the Bab-al-Mandeb Strait have been targeted by the Yemeni Houthi group. Ostensibly undertaken in solidarity with HAMAS as the group continues to fight the Israel Defence Forces (IDF) in the Gaza Strip, 13 (34%) of the ships attacked have sustained some damage from either drone or anti-ship missile strikes. Additionally, two other commercial ships have been targeted to the southeast, in the Indian Ocean, in attacks that were almost certainly a part of the same campaign. Notwithstanding, no casualties have been reported and nearly all of the vessels have been able to proceed to port subsequently. There have also been six probable attempts to hijack vessels in the Red Sea, but gunmen have succeeded in boarding only two of the ships targeted.

In response, since 11th January 2024, the US and UK have conducted at least three waves of joint airstrikes against targets in Yemen to degrade Houthi capability. Washington has also ordered its aircraft to conduct an unknown number of unilateral missions against similar sites. Exactly how much punishment Houthi targets have taken is impossible to assess, but their intent is undented as their attacks continue at a rate of between two and three per week.

Why Haven’t the Houthi Attacks Been More Effective?

The true military capability of the Houthis is something of a moot point. However, the recent attacks in the Red Sea and Gulf of Aden are indicative of a group well-supplied with drones and a variety of anti-ship missiles of mainly Iranian and former Soviet Bloc providence. The majority have likely been supplied directly by Iran or purloined during the Yemeni civil war. Media reporting also indicates that the Houthis have developed something of a homegrown industry for manufacturing their own weaponry - or at least copying that supplied by Tehran. As recently as 11th January this year, a team of US Navy SEALs attached to the 5th Fleet intercepted a dhow en route from Somalia to Yemen and found "Iranian-made ballistic missile and cruise missiles components".

History shows that even military vessels can be put out of action by relatively cheap, unmanned drones. On the night of 31st January 2024, the Russian Tarantul-class missile boat, the Ivanovets, was sunk after being hit by five Ukrainian Magura V5 drones in the Black Sea. Each Magura costs around $273,000 as compared to $70 million for the Ivanovets, which was capable of carrying four anti-ship missiles. This is not a bad return on a small investment for a country with a navy consisting mainly of small patrol vessels. Moreover, in late 2023, the UK government estimated that Russia had lost up to 20% of its Black Sea fleet tonnage to such Ukrainian attacks.

Looking further back, in October 2000, two al-Qaeda suicide bombers crashed a small, fibreglass Zodiac speedboat packed with explosives into the side of the USS Cole, a $1 billion American Arleigh Burke guided-missile destroyer of the same class as the USS Carney, which is currently operating in the Red Sea. At the time, she was refuelling in Aden, Yemen, and 17 of her sailors were killed and 37 others injured. This attack took place long before remote-controlled drones and the success of such an operation now would not have to depend on suicide bombers willing to steer a device onto its target. Indeed, a worrying development came on 11th February, when US Central Command reported that one of its vessels had destroyed “two remotely controlled explosive-laden boats”. Also known as Unmanned Surface Vehicles (USV), they were somewhere near the Yemeni port of Hodeidah at the time. In another first one week later, the US military also claimed to have destroyed a Houthi unmanned underwater vessel (UUV) somewhere near the coast of Yemen.

The most serious Houthi attack to date was the 18th February missile strike on the Rubymar, in the Bab al-Mandeb Strait. At the time of writing, unconfirmed reporting suggested that the crew may have had to abandon ship, although none were injured. Although given their bulk, large commercial vessels are quite difficult to sink, their size, low speed and lack of drone or missile countermeasures makes them relatively easy targets. Since the start of the Houthi campaign in the Red Sea, the international press has widely reported that US, UK and French military vessels have shot down missiles or drones on a number of occasions, almost certainly preventing more serious damage. However, with the Ukrainians proving that even military vessels can be sunk with drones, this does beg the question of why the Houthi attacks in the Red Sea have not caused more damage or casualties.

Source: The BBC

First of all, the Ukrainians may simply be better equipped and have the advantage of intelligence support from their NATO allies, making their task easier than that of the Houthis. Additionally, there have been some signs that the recent US and UK airstrikes are impeding Houthi freedom of movement in the Red Sea. On 6th February, a British-owned ship named the Morning Tide was hit by a probable drone which, according to unconfirmed reporting, may have been launched from a nearby vessel rather than from on land. If this was the case, it might suggest that the air attacks are limiting Houthi freedom to launch projectiles from coastal areas. Indeed, three days before the Morning Tide attack, the US military reported that it had identified six anti-ship missiles ready for firing and destroyed them prior to launch.

However, even if this is taken into account, the amount of reported damage from the Houthi attacks to date does seem low. As described earlier, 15 vessels have been hit by their extensive anti-ship arsenal, making it probable that the lack of damage or casualties is a question of intent rather than capability. If given totally free rein, the Houthis probably could cause more damage. One only has to look at their extremely professional hijacking of the Galaxy Leader on 19th November 2023. Although all the talk across the Middle East is currently that of “escalation” between Israeli, the US and their allies and Tehran’s “Axis of Resistance”, there does not appear to be any desire for widening conflict.

A further positive indication of this came on 18th February but passed almost unnoticed as the international media focused on the death of the Russian opposition leader, Alexi Navalny. It was reported that Brigadier General Esmail Qaani, the commander of the Iranian Revolutionary Guards Corps (IRGC) Quds Force, had met the leaders of several unnamed militant groups affiliated with Tehran at Baghdad International Airport (BIAP) in late January and instructed them to cease operations against US targets in Iraq. At the time of writing, his diktat seems to have been respected as there had been no such strikes reported since 4th February.

Tower 22

On 28th January, three American servicemen and women were killed when what was almost certainly a drone fired by Kataib Hezbollah - one of Iran’s Iraq proxy militias - struck an isolated base known as “Tower 22”, in northeastern Jordan. They were the first reported US casualties in the region since the HAMAS attack on 7th October. President Biden promised retaliation and this duly came on 2nd February 2024, when 85 targets across Syria and Iraq were hit by aircraft and missiles in a thirty minute window.

Notwithstanding, the gap of nearly one week between the Tower 22 strike and the evening of 2nd February is a little curious. With the entire Dwight D. Eisenhower Carrier Strike Group at his disposal in the region - not to mention the US Fifth Fleet based not far to the north in Bahrain - Biden could probably have struck much earlier if he had chosen to. In addition, the President advertised his intention to attack several days before any aircraft took off, leading to the suspicion that he wanted to minimise casualties, giving Tehran more of a slap on the wrist than a major blow which could have increased the temperature across the region substantially. It is probably no coincidence that a spokesman for Harakat al-Nujaba, one of Iran’s Iraq proxies, subsequently claimed that the US targets in the country were “devoid of fighters and military personnel at the time of the attack”.

This apparent tit-for-tat modus operandi can be compared to the ongoing situation on the Israel-Lebanon border. Since the 7th October HAMAS attack, the IDF and Hezbollah - Iran’s most powerful franchise in the Levant - have been engaged in daily, set-piece melees involving missile and rocket fire. The casualties reported - 146 on the Lebanese side of the frontier - have been comparatively low so far.

What Lies Ahead?

At this time, there are no signs that any of the main actors in the Middle East are looking for an escalation of violence. However, the Houthis could, almost certainly, conduct more effective attacks if they chose to, or were ordered to by Tehran. Even though they may bristle with sensors, the USS Cole attack showed that Western combat vessels are not infallible, even to small boats. Moreover, they only carry a finite number of weapons with which to counter the drone and missile threat from the Yemen coastline. Swarming much larger ships with multiple smaller vessels is an established Iranian modus operandi in the Persian Gulf and this could be quite easily transferred to drone operations, potentially overwhelming radars or onboard defence systems. Notwithstanding, there is no obvious intent to conduct any such operation at the moment.

Before the lethal drone attack against Tower 22 on 28th January this year, there had been some 160 strikes against US military assets in Syria and Iraq since the start of the HAMAS-Israel conflict in October 2023, none of them causing any major casualties or damage. Although it might be tempting to regard the three deaths at Tower 22 as an Iranian “escalation”, it is probable that this attack was no different in intent from any of the other previous 160; for whatever reason, the single drone just happened to get through US defences and strike home. Indeed, there has been some suggestion that it may have been mistaken by air defences for an inbound friendly aircraft, giving it unimpeded passage to its target.

A comparable threat does exist in the Red Sea and Gulf of Aden. The more missiles and drones launched by the Houthis, the greater the chance that one or two might just penetrate defences and cause much greater destruction and casualties to a commercial or even military vessel. The current situation in the Middle East is one of measured response by Washington and its allies on the one side and the “Axis of Resistance” on the other. However, there is a danger of unintended escalation attendant upon an attack such as that which occurred at Tower 22.

As a final word, Islam’s Holy Month of Ramadan is now fairly imminent, this year falling between 10th March and 9th April. Historically, the international media has tended to equate this period with an uptick in Islamic terrorist violence, but the evidence for this is largely anecdotal. During the Iraq insurgency following the US-led invasion of 2003, increases in mass casualty attacks during Ramadan and on other key dates in the Islamic calendar were a result of these attracting large numbers of people onto city streets to mark Iftar - the breaking of the Ramadan fast every evening - or to conduct pilgrimages. The strikes were not planned to specifically mark important dates. As things stand, there is no suggestion that Ramadan will have any significant impact on the Houthi campaign against international shipping.