A Strait Betwixt Two

As the Yemeni Houthi group's assault on maritime vessels continues to escalate, the risk to key commodity supply chains raises global concern. As analysed in this series' previous article (available here), conflict escalation impacts the region's security, impacting key trade routes and global trade patterns. The Suez Canal is a key trade route whose stability and security could impact and shift trade dynamics. As the search for alternative trade routes ensues, the Strait of Hormuz makes use of a power vacuum to expand its influence.

Suez Canal

The Suez Canal is a 193-kilometre waterway that connects the Red Sea to the Mediterranean Sea. Approximately 12% of global trade passes through the Canal, granting it vast economic, strategic, and geopolitical influence on a global scale. This canal shortens maritime trade routes between Asia and Europe by approximately 6,000 km by removing the need to export around the Cape of Good Hope and serves as a vital passage for oil shipments from the Persian Gulf to the West. Approximately 5.5 million barrels of oil a day pass through the Canal, making it a ‘competitor’ of the Strait of Hormuz.

Global trade via the Suez Canal is likely to decrease as a result of the rising tensions near the Bab el-Mandeb Strait. Due to their geographic predispositions, the Bab el-Mandeb Strait and the Suez Canal are interdependent; bottlenecks in either trade choke point will have a knock-on effect on the other. Bottlenecks caused by Houthi aggression against ships in the strait are likely to redirect maritime traffic from the Suez Canal to alternative passageways. From November to December 2023, the volume of shipping containers that passed through the Canal decreased from 500,000 to 200,000 per day, respectively, representing a reduction of 60%.

Suez Canal Trade Volume Differences (metric tonnes)

The overall trade volume in the Suez Canal has decreased drastically. Between October 7th, 2023, and February 25th, 2024, the channel’s trade volume decreased from 5,265,473 metric tonnes to 2,018,974 metric tonnes. As the weaponization of supply chains becomes part of regional economic power plays, there is a global interest in decreasing the vulnerability of vital choke points via trade route diversification. The lack of transport routes connecting Europe and Asia has hampered these interests, making choke points increasingly susceptible to exploitation.

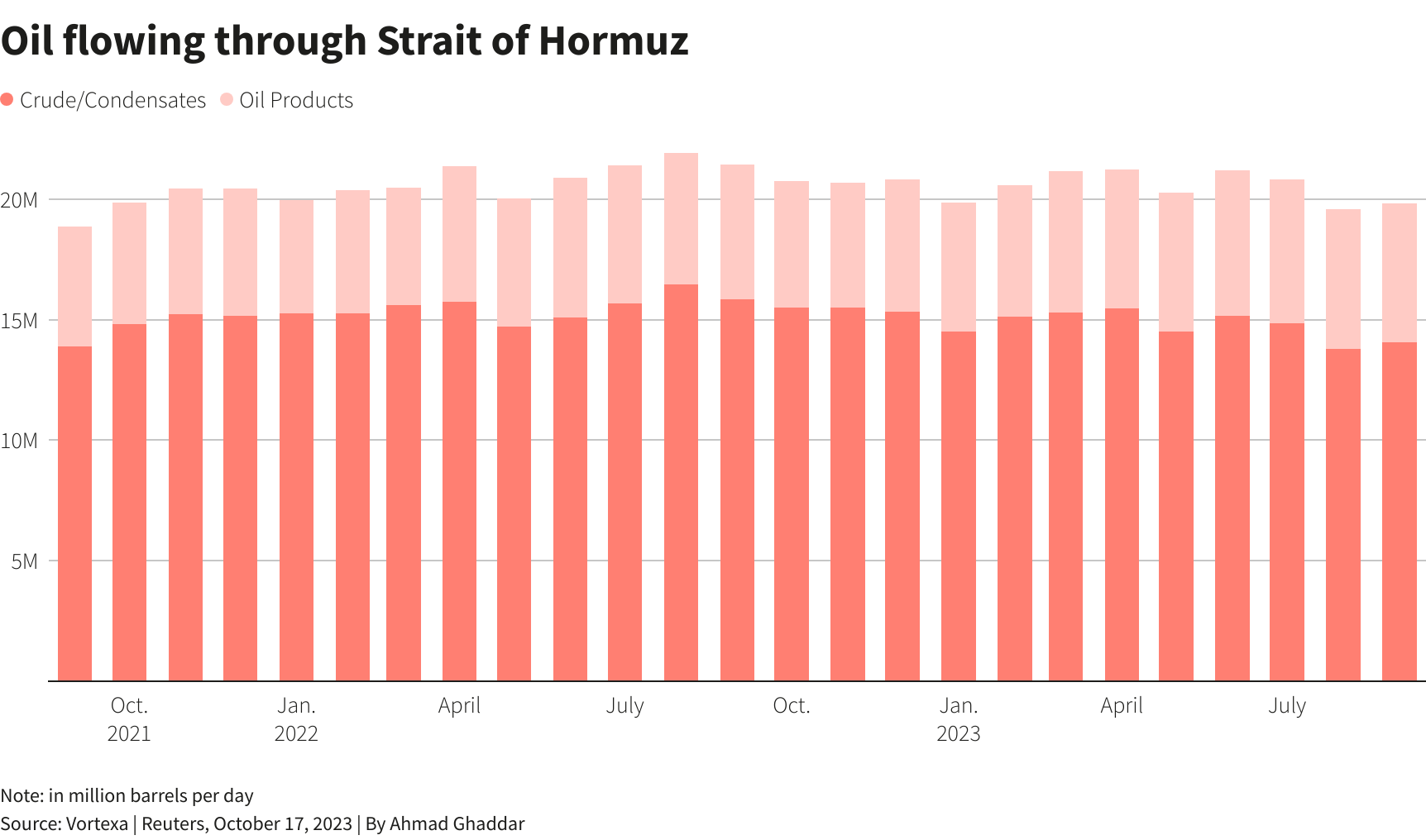

Oil Trade Volumes in Millions of Barrels per Day in Vital Global Chokepoints

Source: Reuters

Quantitative Analysis

Many cargoes have been rerouted through the Cape of Good Hope to avoid the Red Sea region since the beginning of the Houthi conflict. Several European automakers announced reductions in operations due to delays in auto parts produced in Asia, demonstrating the high exposure of sectors dependent on imports from China.

In the first two weeks of 2024, cargo traffic decreased by 30% and tanker oil carriers by 19%. In contrast, transit around the Cape of Good Hope increased by 66% with cargoes and 65% by tankers in the same period. According to the analysis of JP Morgan economists, rerouting will increase transit times by 30% and reduce shipping capacities by 9%.

Depiction of Trade Route Diversion

Source: Al Jazeera

More fuel is used in the rerouted freight, an additional cost that increases the risk of cargo seizure and results in elevated shipping rates. The most affected routes were from Asia towards Europe, with 40% of their bilateral trade traversing the Red Sea. The freight rates of the north of Europe until the Far East, utilising the large ports of China and Singapore, have increased by 235% since mid-December; freights to the Mediterranean countries increased by 243%. Freights of products from China to the US spiked 140% two months into the conflict, from November 2023 to January 25, 2024. The OECD estimates that if the doubling of freight persists for a year, global inflation might rise to 0.4%.

The upward trend in freight rates can be seen in the graphic pictured below, depicting the “Shanghai Containerised Freight Index” (SCFI). The index represents the cost increase in times of crisis, such as at the beginning of the pandemic, when there were shipping and productive constraints, and more recently, with the Houthi rebel attacks. Most shipments through the Red Sea are container goods, accounting for 30% of the total global trade. Companies such as IKEA, Amazon, and Walmart use this route to deliver their Asian-made goods. As large corporations fear logistic and supply chain risk, more crucial trade volumes could be rerouted.

Shanghai Containerized Freight Index

Energy Commodity Impact

Of the commodities that traverse the Red Sea, oil and gas appear to be the most vulnerable. Before the attacks, 12% of the oil trade transited through the Red Sea, with a daily average of 8.2 million barrels. Most of this crude oil comes from the Middle East, destined for European markets, or from Russia, which sends 80% of its total oil exports to Chinese and Indian markets. The amount of oil from the Middle East remained robust in January. Saudi oil is being shipped from Muajjiz (already in the Red Sea) in order to avoid attack-hotspots in the strait of Bab al-Mandeb.

Iraq has been more cautious, contouring the Cape of Good Hope and increasing delays on its cargo. Iraq's oil imports to the region reached 500 thousand barrels per day (kbd) in February, 55% less than the previous year's daily average. Conversely, Iraq's oil imports increased in Asia, signalling a potential reshuffling of transport destinations. Trade with India reached a new high since April 2022 of 1.15 million barrels per day (mbd) in January 2024, a 26% increase from the daily average imports from Iraq's crude.

Brent Crude and WTI Crude Fluctuations

Source: Technopedia

Refined products were also impacted. Usually, 3.5 MBd were shipped via the Suez Canal in 2023, or around 14% of the total global flow. Nearly 15% of the global trade in Naphta passes through the Red Sea, amounting to 450 kbd. One of these cargoes was attacked, the Martin Luanda, laden with Russian naphtha, causing a 130 kbd reduction in January compared with the same month in 2023. Traffic to and from Europe is being diverted in light of the conflict. Jet fuel cargoes sent from India and the Middle East to Europe, amounting to 480 kbd, are avoiding the affected region, circling the Cape of Good Hope.

Due to these extra miles and higher speeds to counteract the delays, bunker fuel sales saw record highs in Singapore and the Middle East. The vessel must use more fuel, and bunker fuel demand increased by 12.1% in a year-over-year comparison in Singapore.

In 2023, eight percent, or 31.7 billion cubic metres (bcm), of the LNG trade traversed the Red Sea. The US and Qatar exports are the most prominent in the Red Sea. After sanctioning Russia's oil because of the Ukrainian War, Europe started to rely more on LNG shipments from the Middle East, mainly from Qatar. The country shipped 15 metric tonnes of LNG via the Red Sea to Europe, representing a share of 19% of the Qatari LNG exports. Vessels travelling to and from Qatar will have to circle the Cape of Good Hope, adding 10–11 days to travel times and negatively impacting cargo transit.

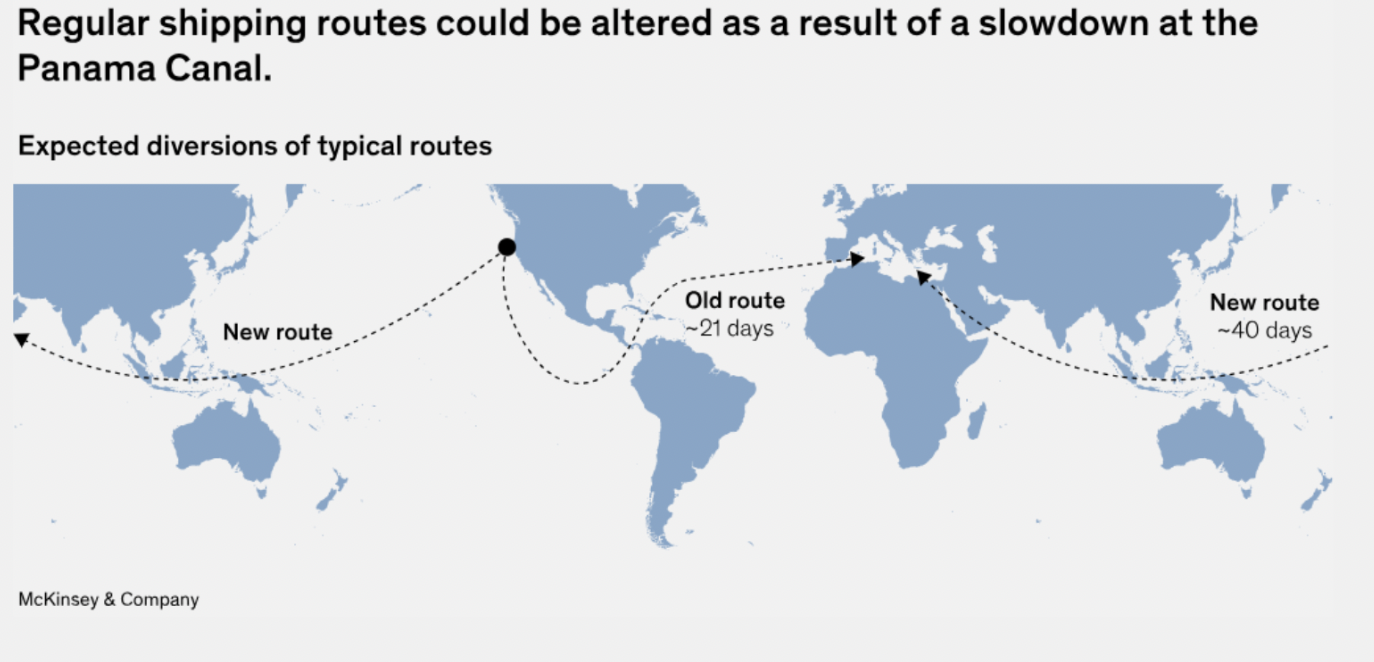

US LNG export capacity has increased in the past few years, sending shipments to Asia via the Red Sea. The Panama Canal receives many LNG cargoes from the US via the Pacific, yet its traffic limitations cause US cargo to be routed through the Atlantic and the Red Sea. The figure “Trade Shipping Routes” below displays the dimensions of the shifts that US LNG cargoes must take in the absence of passage via the Panama Canal.

Trade Shipping Routes

Source: McKinsey & Company

Until January 15, at least 30 LNG tankers were rerouted to pass through the Cape of Good Hope instead. Russia's LNG shipments to Asia are currently avoiding the Red Sea, and Qatar did not send any new shipments in the last fortnight of January after the Western strikes at Houthi targets.

Risk Assessment

A share of 12% of oil tankers, ships designed to carry oil, and 8% of liquified gas pass through this route towards the Mediterranean. Inventories in Europe are still high, but if the crisis persists for several months, energy prices could be aggravated. As evidenced by the sanctions against Russia, cargo reshuffling is possible. Qatar can send its cargoes to Asia, and those from the US can go to European markets, allowing suppliers to effectively avoid the Red Sea.

Around 12% of the seaborn grains traversed the Red Sea, representing monthly grain shipments of 7 megatonnes. The most considerable bulk are wheat and grain exports from the US, Europe, and the Black Sea. Around 4.5 million metric tonnes of grain shipments from December to February avoided the area, with a notable decrease of 40% in wheat exports. The attacks affected Robusta coffee cargoes as well. Cargoes from Vietnam, Indonesia, and India towards Europe were intercepted, impacting shipping prices and incentivizing trade with alternative nations.

Daily arrivals of bulk dry vessels, including iron ore and grain from Asia, were down by 45% on January 28, 2024, and container goods were down by 91%. However, further significant disruptions to agricultural exports are not expected. Most of the exports from the US, a large bulk, were passing through the Suez Canal to avoid the congestion of the Panama Canal due to the droughts that limited the capacity of circulation. These cargoes are now traversing the Cape route.

Around 320 million metric tonnes of bulk sail through Suez, or 7% of the world bulk trade. No significant impacts are predicted for iron ore or coal, which represented 42 and 99 megatonnes of volume, respectively, shipped through the Red Sea in 2023. Most of the dry bulks that traverse the impacted region can be purchased from other suppliers, precluding significant supply disruptions.

As of March 1st, reports show that only grain shipments and Iranian vessels were passing through the Red Sea. There were no oil or LNG shipments with non-Iranian links in the Red Sea. These developments illustrate the significant trade shifts caused by the Red Sea crisis. As of today, a looming threat lies in the Houthis’ promises of large-scale attacks during Ramadan. The lack of intelligence on the Houthi’s military capacity and power makes it difficult to ascertain the extent of future conflicts, generating further uncertainty in commercial trade.

The Strait of Hormuz

The Strait of Hormuz is a channel that connects the Persian Gulf to the Gulf of Oman, providing Iran, Oman, and the UAE with access to maritime traffic and trade. The strait is estimated to carry about one-fifth of the global oil at a daily trade volume of 20.5 million barrels, proving to be of vital strategic importance for Middle Eastern oil supply the world’s largest oil transit chokepoint. The strait is a prominent trade corridor for a myriad of oil-exporting nations, namely the OPEC members Saudi Arabia, Iran, the UAE, Kuwait, and Iraq. These nations export most of their crude oil via the passage, with total volumes reaching 21 mb of crude oil daily, or 21% of total petroleum liquid products. Additionally, Qatar, the largest global exporter of LNG, exports most of its LNG via the Strait.

Geographic Location of Strait of Hormuz

Source: Marketwatch

Although the strait is technically regulated by the 1982 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, Iran has not ratified the agreement. Through its geostrategic placement, Iran can trigger oil price responses through its influence on trade transit, establishing the country’s regional and global influence.

Strait of Hormuz Oil Volumes

Source: Reuters

Experts are particularly worried that the turbulence is likely to spread to the Strait of Hormuz now that Iran backs the Houthis in Yemen and might want to support their cause by doubling down regionally. However, this is something that would cause a lot of backlash in the form of a further tightening of economic sanctions against Tehran, which might deter further provocations.

Despite Iran’s previous threats to block the Strait entirely, these have never gone into effect. Diversifying trade routes to avoid supply shocks and bottlenecks is of interest to regional oil-exporters dependent on the route for maritime trade access. Such diversification attempts have already been undertaken, as seen by the UAE and Saudi Arabia's attempts to bypass the Strait of Hormuz through the construction of alternative oil pipelines. The loss of trade volume from these two producers, holding the world's second and fifth largest oil reserves, respectively, severely hindered the corridor’s prominence.

The attacks on the Red Sea might cause damage to the oil and LNG cargo from countries in the Persian Gulf, increasing costs for oil and gas exporters. However, cargoes could find alternative destinations. The vast Asian markets, which face a shortage of energy products due to a loss of trade through the Red Sea, could be a potential suitor. Finding new LPG (liquefied petroleum gas) contracts could be beneficial for Iran, and its recently enhanced production capacity could supply various markets.

Geopolitics and Prospects for a Route Shift

Although the Strait of Hormuz stands to capture diverted trade flows from the Suez Canal, its global influence is still limited by Iran’s geopolitical ties. As exemplified by the Iran-US conflict, Iran’s conflicts can severely impact traffic through the Strait, significantly impacting the stability of the route and prospects for future growth.

Although security and stability are of paramount importance to trade, efforts to provide these traits could be counterproductive. On March 12th, China and Russia conducted maritime drills and exercises in the Gulf of Oman with naval and aviation vessels. According to Russia's Ministry of Defence, this five-day exercise sought to enhance the security of maritime economic activities using maritime vessels with anti-ship missiles and advanced defence systems. Over 20 vessels were displayed in this joint naval drill, attempting to lure trade through the promise of stability and security.

Whether meant as a display of power or a promise of security, the pronounced presence of Russian and Chinese forces could aggravate geopolitical tensions and increase the potential for conflict in the region, driving global trade prospects down. With precedents of trade conflict, such as the IRGC’s seizure of an American oil cargo in the Persian Gulf on January 22nd, various countries might be sceptical of rerouting commodity trade through the Strait.

Tensions are also aggravated by Iran’s alleged assistance in the Houthi attacks. The US has supposedly communicated indirectly with Iran to urge them to intervene in the region. China and Russia’s interest in improving the Strait’s trade prospects would benefit from a de-escalation of the Houthi conflict, as shown by China’s insistence on Iran’s cooperation in the Houthi conflict. As the conflict stands, the Strait’s prospect as an alternative trade route is dependent not only on Iran’s reputation and presence in global conflicts but also on the route’s patrons and proponents.

Conclusion

The extent to which the Strait of Hormuz could benefit from trade diversion depends not only on its ability to pose itself as a viable trade route but also on the duration of the Houthi conflict. In order to capture trade volumes and increase international trade through the route, Iran would have to ameliorate its geopolitical ties and provide stability to compete with rising prospective trade route alternatives. Although the conflict in the Suez has yet to show promising signs of de-escalation, securing the Suez would likely cause previous trade volumes to resume and restore its hegemony in commodity trade. It remains to be seen whether the conflict will endure long enough to allow other trade routes to be established as alternatives and permanently shift power balances in global trade.