Serbia’s Jadar mine: the energy transition and environmental concerns

Introduction

Following government plans to reboot the Jadar lithium mine proposed by mining giant Rio Tinto, thousands of protesters rallied in Belgrade over the past month. The mine is set to become the largest lithium mine in Europe, significantly boosting Serbia’s economy, and supplying 90% of Europe’s lithium needs. However, the project has also sparked nationwide protests with concerns over the potential impact of the mine on the local environment. With increasing global demand for critical minerals, the Jadar lithium mine highlights broader tensions around resource extraction and the energy transition. This article analyses the implications of the mine and explores the different stakeholder perspectives that pose risks to its commencement.

Background

With the European Union's (EU) increasing demand for lithium, driven by the transition to electric vehicles (EVs) and energy storage, developing a secure lithium supply chain is growing in importance. Portugal is the only EU state that mines and processes lithium, making the region and its green transition heavily dependent on external sources. In response to this vulnerability, the EU has introduced the Critical Raw Materials Act (CRMA), which aims to reduce reliance on imports by promoting domestic production and refining capabilities. The proposed Jadar lithium mine in Serbia, with estimated reserves amounting to 158 million tons, could play a pivotal role in this strategy, with plans to produce 58,000 tons of lithium annually – enough to support 17% of the continent's EV production, approximately 1.1 million cars.

If all goes to plan, mining operations could begin in 2028. According to Serbia’s mining and energy minister, the government “aims to incorporate refining processes and downstream production, such as manufacturing lithium carbonate, cathodes, and lithium-ion batteries, potentially extending to electric vehicle production”. Moreover, in June 2021, amid public opposition in the Loznica region, the government emphasised that the project would involve a full-cycle approach to maximise local economic benefits. In March, Prime Minister Ana Brnabić suggested that the country could restrict or prohibit the export of raw lithium to support domestic value chain development. However, so far the specifics of the refining processes remain unclear.

Stakeholder perspectives

EU view

Since Europe currently has virtually no domestic lithium production, the EU views the Jadar lithium mine as a crucial project to bolster its economic security and support its green energy transition. The mine is expected to produce enough lithium to meet 13% of the continent’s projected demand by 2030, reducing its reliance on imports. Germany has already expressed strong support for the project, with Chancellor Scholz emphasising the mine’s importance for Europe's economic resilience.

Serbian view

The Serbian government views the project as a significant opportunity for the country's economy and its industrial development. Its mining and energy minister has emphasized that the project would comply with EU environmental standards while delivering economic benefits, including the creation of around 20,000 jobs across the entire value chain. Furthermore, Serbia’s finance minister projects that the mine could add between €10 billion and €12 billion to Serbia's annual GDP, which was €64 billion in 2022. To maximize these benefits, Serbia plans to follow the example of countries like Zimbabwe and Namibia by imposing restrictions on lithium exports, aiming to establish a complete domestic value chain for EVs. Additionally, Serbia's bid for EU membership adds a strategic dimension to the project, potentially aligning the country more closely with the bloc's energy and economic goals.

Local population view

Massive protests against the Jadar project have erupted across Serbia since June, following a court decision that cleared the way for the government to approve the mine. Many Serbians are troubled by the lack of transparency that evolved in the granting of mining rights to a foreign company. Moreover, opponents are sceptical of Rio Tinto's involvement, citing the company’s controversial history in developing countries, such as its operations in Papua New Guinea, where environmental damage contributed to a nine-year civil war. In this light, locals fear that the mine could jeopardise vital food and water sources in the Jadar Valley. For example, environmental problems caused by tailings, mine wastewater, noise, air pollution, and light pollution could endanger the lives of numerous communities and harm their agricultural land, livestock, and assets. Concerns have also been heightened by reports that exploratory wells drilled by Rio Tinto brought water to the surface that killed surrounding crops and polluted the river.

Rio Tinto view

Rio Tinto asserts that the Jadar mine is “the most studied lithium project in Europe,” having invested over $600 million in research and development to ensure its safety. As part of its efforts to gain public support, the company has conducted 150 information sessions for the local community, while Serbia's mining ministry has established a call centre to address concerns about the project. To further reassure the public, Rio Tinto has also expressed a willingness to allow independent experts to conduct an environmental review, aiming to alleviate doubts about the mine's potential impact on the ecosystem.

Conclusion

Despite the public opposition, the Jadar lithium mine appears likely to proceed, backed by strong support from the Serbian government and the EU, both eager to meet the onshoring requirements outlined in the CRMA. However, as this article has highlighted, the project faces considerable risks, including environmental challenges and persistent social and political opposition. The recent closure of the Cobre copper mine in Panama, following widespread protests over environmental damage and disputes over a new tax deal, serves as a stark reminder of the potential pitfalls. The Jadar project will need to navigate these complexities carefully to avoid similar outcomes and ensure a balanced approach to economic development and environmental preservation.

Drilling Dreams, Sinking Realities

Introduction

Climate change is increasingly recognised as the most significant long-term downside risk to almost all investment sectors. This urgency is underscored by the approaching 2024 U.S. Presidential election, where energy policy is a key issue, particularly in the context of the Republican Party’s push to revive the fossil fuel industry. With global temperatures in 2023 reaching unprecedented highs and surpassing even the most dire projections, the severity of climate-related disasters has escalated. These developments make it clear that mitigating climate change is not just an environmental imperative but also a critical economic and geopolitical challenge. The outcome of the U.S. election could have profound implications for global energy policies, especially as the Republican nominee, Donald Trump, advocates for an aggressive expansion of fossil fuel production.

Increasing Severity of Climate Disasters

2023 has been a stark reminder of the accelerating impacts of climate change. Record-breaking global temperatures, partly driven by an El Niño intensified by climate change, have led to widespread heatwaves, wildfires, and other extreme weather events. These developments have surpassed the projections of most climate models, highlighting the increasing unpredictability and severity of climate-related disasters, and the real-world implications of inaction on climate policy. The nonlinear trajectory of ecosystem collapse is one that has far-reaching implications, affecting everything from agriculture and infrastructure to public health and economic stability.

Graph 1.0 (Global Temperature Trends)

As the graph above shows, 2023 surpassed every previous temperature record by-far; almost showing an off-the-charts uptick in increasing temperatures. This must be seen in the context of the political economy of the green energy transition, involving stakeholders like big-oil to employ significant effort to subdue, delay, and slow down momentum of green energy through extensive lobbying in an effort to stay relevant in a world where renewable energy has become cheaper than conventional oil and gas as shown in the graph below.

Graph 2.0 (Energy cost by source)

COP and Delayed Multilateral Action

The international community has attempted to make some progress toward addressing climate change, with the United Nations’ Conference of the Parties (COP) serving as a central platform for multilateral action. COP 28 in Dubai marked a significant moment, signalling what many hoped would be the beginning of the end for fossil fuels. However, the subsequent COP 29, hosted in Baku, Azerbaijan—also a petro-state—seems to have reduced the pace and effectiveness of global climate action, and put the world off-track to limit global warming to 1.5C. The influence of fossil fuel interests and lobbying has continued to slow progress, delaying the implementation of much-needed measures to reduce emissions on a global scale, which by the number of lobbyists in COP 26 for instance, outnumbered national delegations to the convention.

Graph 3.0 (number of lobbyists in COP 26)

The 2024 U.S. Presidential Elections

The 2024 U.S. Presidential election represents a pivotal moment for the country’s energy policy, particularly in the context of climate change. Donald Trump’s acceptance speech at the Republican National Convention on July 19th highlighted his intent to revive America’s fossil fuel industry. Declaring, “We will drill, baby, drill!” Trump pledged to ramp up domestic fossil fuel production to unprecedented levels, with the aim of making the United States "energy dominant" on the global stage. His commitment to this vision was evident in his efforts to court oil industry leaders, promising to roll back President Joe Biden’s environmental regulations in exchange for financial support for his re-election campaign.

Trump’s team argues that unleashing vast untapped oil reserves in regions like Alaska and the Gulf of Mexico could significantly boost production if environmental regulations were eased. However, experts contend that such plans might not significantly alter the U.S. energy landscape, whether fossil or renewable. Despite the oil industry’s grievances under Biden, the sector has seen substantial growth, with oil and gas production reaching record levels. Biden’s administration has issued more drilling permits in its first three years than Trump did during his entire term, and the profits of major oil companies have soared due to the 2020s global commodities boom.

Federal Policy and Oil Production

The impact of federal policy on oil production is often tempered by broader market dynamics and investor behaviour. The oil industry, particularly after the financial strains of the shale boom, now prioritises capital discipline, driven more by market conditions and Wall Street’s influence than by the White House’s policies. Even if Trump were to win the presidency, the overall trajectory of oil production is likely to continue being shaped by global supply-demand balances and the strategic decisions of organisations like OPEC.

Interestingly, Trump’s promise to repeal Biden’s Inflation Reduction Act (IRA)—which includes substantial subsidies for green energy—may face significant obstacles. The IRA’s benefits are largely concentrated in Republican districts, and industries traditionally aligned with fossil fuels are beginning to recognise the advantages of low-carbon technologies. For example, companies benefiting from the IRA’s subsidies for hydrogen and carbon capture are prepared to defend these incentives against any potential repeal.

Conclusion

The urgency of addressing climate change is often underestimated due to a common misunderstanding of the non-linear feedback loops involved in ecosystem collapse. Many tend to view emissions as a simple, transactional force with nature, failing to grasp the exponential and potentially catastrophic consequences of inaction. This underestimation leads to a dangerous complacency, undervaluing the need for urgent and robust policy action.

The U.S. holds significant sway over global climate outcomes mainly because of two reasons: (1) It is the second largest emitter; and (2) it is one of the only countries in the world for climate policy to be a partisan issue, making it particularly susceptible to hampering global emissions targets.

With much of the Global South still dependent on coal, oil, and gas, a unilateral decision by the U.S. to aggressively increase fossil fuel consumption could single-handedly push the planet toward an irreversible climate disaster. The stakes are incredibly high, especially as the political economy of the green transition faces opposition from entrenched fossil fuel interests. These forces work to delay and obstruct the shift to renewable energy, despite the clear and present need to accelerate this transition to prevent ecological collapse.

Having already surpassed 1.5C warming; the world is headed towards 4.1-4.8C warming without climate action policies; 2.5-2.9C warming with current policies; and 2.1C warming with current pledges and targets. In this context, if the U.S. were to aggressively change course and begin burning more, instead of less as Trump suggests—it may severely hamper the ability of the global ecosystem to recover and restore, potentially breaching already critical tipping points.

Graph 4.0 (projected warming in different scenarios)

Therefore, it becomes more important than ever for climate-conscious energy policy, to recognise that ecological collapse is a non-linear and irreversible outcome of breaching environmental tipping points, and to underscore the need to prevent misinformation on climate change spreading as a result of forces acting against renewable energy in the political economy of the green transition.

The good news, however, may be that while Republicans may advocate for a new oil boom, the realities of global markets and investor behaviour suggest a different outcome. Wall Street, driven by a cost-benefit analysis that increasingly favours renewable energy, may not align with the interests of a pro-fossil fuel administration. Although the White House can influence energy policy, it is ultimately market forces that will dictate the future of America's energy landscape. This shift towards green energy, driven by economic viability and technological advancements, underscores the need for accelerated action to mitigate climate risks and ensure a sustainable future.

Nickel and Dime: The Philippines' Approach to Attracting Western Capital

Introduction

Aware of the integral role of critical minerals in clean energy systems and other modern technologies, the Philippines has begun courting Western investment to develop its domestic critical mineral industry. The country has vast reserves of untapped natural resources, including nickel, a critical component of electric vehicle (EV) batteries. According to the International Energy Agency, global demand for nickel is expected to increase by approximately 65% by the end of the decade. The Philippines stands to financially benefit from the expected surge of demand for nickel in the coming years, but must first build the requisite infrastructure (e.g., mines, refining plants, processing facilities, transport hubs, etc.) to realise the economic potential of this mineral resource.

To attract increased foreign investment, the Philippines is positioning itself as an alternative to China in the global nickel supply chain. This stance draws from the rationale that the United States (U.S.) and other Western countries will want to diversify their critical mineral supply chains away from China given contemporary security concerns with China and its dominance over nickel supplies and processing capabilities. Such a strategy has both geopolitical and economic implications, especially as it relates to strategic trading and investment blocs that reflect the U.S.-China power competition. By aligning with Western interests, the Philippines aims to bolster its economic growth while contributing to a more balanced global supply chain for critical minerals.

Nickel Industry in the Philippines

The Philippines is currently the world’s second-largest supplier of nickel, accounting for 11% of global production. The country’s nickel exports are expected to increase over the next couple of years to meet growing global demand, particularly in the EV sector. However, this outlook depends on how the country navigates other political and economic factors, including (1) volatility in market prices; (2) trade relations and international partnerships; (3) ability to attract foreign investment; (4) the implementation of government policies that promote industry development; and (5) environmental, social, and governance considerations. The Philippines Government has seemingly decided that, at its current stage, the best way to develop the country’s nickel production capacity is by focusing on boosting foreign investment in the domestic nickel industry.

Investment Strategy

Indonesia is the largest global supplier of nickel, producing over 40% of the world’s nickel in 2023. Approximately 90% of Indonesia’s nickel industry is controlled by Chinese companies, giving China a dominant market position over nickel. The market concentration of this critical mineral has caused unease and consternation amongst Western nations that fear China may leverage this control over the global nickel supply chain to their disadvantage. The Philippines, which itself has experienced escalating tensions with China over territorial claims in the South China Sea, has leveraged this fear, attempting to use it to spur greater foreign investment in their own nickel industry. Through this investment, the Philippine government hopes to develop the domestic nickel sector, especially as it relates to downstream processing, where most of the value-added occurs. The investment strategy comes amid a broader effort to augment economic ties and foster greater alignment with the U.S. and its allies, although the country is still open to Chinese investment. Government officials in Manila have shared that the U.S., Australia, Britain, Canada, and European Union have all expressed interest in directing investment to the Philippines’ nickel sector.

To date, there have been a few initiatives to advance the Philippines’ nickel industry. In late 2023, government officials from the Philippines and the U.S. signed a Memorandum of Understanding that provided $5 million to set up a technical assistance programme to develop the Philippines’ critical mineral sector. The leaders of the U.S., Japan, and the Philippines also held an economic security summit in April 2024 that featured discussions on strengthening critical mineral supply chains. Similarly, there have been preliminary talks about a trilateral arrangement in which the Philippines would supply raw nickel, the U.S. would provide financing, and a third country (e.g., Australia) would offer the technology necessary to process and refine the nickel. However, thus far, these discussions have yielded little in the way of concrete financing or investment initiatives that would provide notable benefit to the industry.

Geopolitical and Geoeconomic Implications

While the U.S. and its allies support a diversification of the global nickel supply chain, their ability to shift the paradigm will likely prove to be a difficult undertaking. Strengthening the Philippines’ nickel mining, processing, and refining capacity up to a level in which it will be able to recapture significant market share from Indonesia and China will require a huge amount of economic and political resources. This is something most countries will shy away from incurring in an important election year. For example, the U.S. has communicated its reluctance to sign a critical minerals agreement amidst the 2024 U.S. presidential race. Further, countries will not want to antagonise China and risk retaliation, given that many economies currently rely on China for the production and processing of critical minerals and their downstream technologies.

As a result of major Chinese investment and technological innovation, Indonesia’s production of nickel has notably increased in recent years. This flood of new nickel supplies has put downward pressure on global nickel prices and crowded out competition from entering the market. With slumping prices, it may be a challenge to attract sufficient foreign financing without a policy framework or safeguards that could inspire greater investor confidence. A potential remedy could be regulatory policies and tax incentives that favour non-Chinese companies. Nevertheless, the economic development associated with increased nickel production is integral to the Philippines economy, so the country does not want to alienate Chinese investors if they prove to be the best path forward.

Concluding Remarks

The Philippines’ strategic efforts to develop its nickel industry through Western investment illustrate the dynamics of economic ambition and geopolitical considerations. By positioning itself as a viable alternative to the China-dominated Indonesian nickel industry, the Philippines aims to leverage global security concerns to increase investment in its domestic nickel sector. However, the realisation of this ambition will hinge on overcoming significant political and economic challenges, such as fluctuating prices and dynamic geopolitical tensions. As the country navigates these hurdles, the outcome of its initiatives will significantly impact its role in the global critical minerals supply chain, shaping future economic and strategic alignments.

Mexico’s Election Impact on Energy Policy

Background

On 2nd June 2024, Claudia Sheinbaum made history by being elected as Mexico’s first female president. With a strong academic background, Sheinbaum is a physicist holding a doctorate in energy engineering and was part of the Nobel Peace Prize winning UN panel on climate change. Sheinbaum’s economic agenda aims to capitalise on the opportunities presented by American nearshoring efforts, contingent on a stable and expanding energy supply.

Mexico is one of the largest oil suppliers in the world, having produced 1.6 million barrels daily in 2022. The country is also ranked 13th in the global crude oil output. Whilst Sheinbaum has promised to accelerate Mexico’s clean energy transition and aims to generate 50% of its energy from renewables by 2030, most spectators are divided. Some hope her scientific background will lead to a greater emphasis on clean energy, while others fear she might follow the policies of her predecessor, Andrés Manuel López Obrador, who invested heavily in bolstering fossil fuel-reliant state energy companies, PEMEX (Petróleos Mexicanos) and CFE (Comisión Federal de Electricidad).

Regardless of her position on energy transition, Sheinbaum faces the challenge of restoring investor confidence, which was shaken during López Obrador’s administration. Without this achievement, the new leader cannot guarantee Mexico’s energy stability and it could jeopardise the country’s commitment under the US - Mexico - Canada Agreement (USMCA) and the Paris Agreement.

Mexico’s gas supply, traditionally dominated by PEMEX, faced disruptions due to declining production and pipeline congestions. An energy reform in 2013 allowed private firms to enter the gas market to boost market competition and supply reliability. However, under López Obrador, the private sector participation was viewed as a threat, and efforts were allocated to prioritise PEMEX’s production. Currently, the company is the most indebted oil corporation in the world, with its stocks having a -5.74% 3-year return, compared to +11.48% from other companies in the same period and sector.

Considerations for Sheinbaum’s Energy Strategy

Sheinbaum has a decision to make regarding the energy future of Mexico. There is a confluence of energy-related factors that Sheinbaum will need to consider early in her administration, such as increasing domestic energy demands, pressure from environmental groups and international climate regimes, a deepened reliance on energy imports from abroad, and foreign companies’ dissatisfaction with the state’s current control of the energy sector.

Sheinbaum has long supported the state-centric energy policies of the previous administration, including legislative amendments that rolled back the 2013 constitutional reforms that helped liberalise the Mexican energy sector. Nevertheless, while Sheinbaum continues to defend the energy policies of the previous López Obrador administration, she is more pragmatic than her predecessor, which may provide a path for potential policy change to deal with the various energy issues facing her administration.

One area where Sheinbaum differs from López Obrador is the role of renewable energy sources in Mexico’s energy mix. Sheinbaum has a robust environmental pedigree and has published extensively on the clean energy transition. During her time as mayor of Mexico City, she implemented clean energy infrastructure and electrified transportation modalities. Furthermore, according to her campaign platform, she is committed to progressing Mexico’s clean energy transition and decarbonising the economy. However, climate progress under the Sheinbaum administration is likely to be tempered by fossil fuel supporters. Mexico still strongly depends on the oil and gas industry for its energy needs, accounting for over 80% of its energy mix in 2022. Understanding the necessity of oil and gas for the domestic economy, Sheinbaum has championed domestic oil production and supports the central role of PEMEX in the energy sector.

Source: IEA (2024)

As Mexican energy sovereignty will likely continue to be a focus for Sheinbaum’s administration, issues related to weak foreign direct investment in the Mexican energy industry are likely to persist. Under the current policy framework, private industry does not have an incentive to invest in exploration and production activities in Mexico. Lax private investment coupled with recent financial struggles at PEMEX may result in insufficient investment in Mexico’s energy infrastructure and increased reliance on energy imports. Therefore, to address the increased domestic energy demands, Sheinbaum may alter the government's prevailing energy strategy to ensure sustainable and robust energy supplies by providing private companies more control/access to the energy sector.

There are also broader trade implications regarding Sheinbaum’s potential approach to Mexico’s energy strategy, particularly how it impacts the country’s relationship with the US. The US Trade Representative communicated to its Mexican counterpart that the legislative amendments passed under the López Obrador administration violated investment provisions stipulated by the USMCA, leading the US to open dispute settlement consultations to address the issue. If a negotiated agreement is not reached, the US could invoke trade sanctions targeting Mexico in response. Failure to reaffirm Mexico’s commitment to the trade agreement could also lead to neglect of economic opportunities stemming from American nearshoring efforts.

The outcome of the 2024 U.S. presidential election will undoubtedly further impact Mexico’s energy sector, especially as it relates to trade and investment. Sheinbaum’s industrial policy plans and interest in promoting a green economy align with Biden’s focus on the clean energy transition and nearshoring efforts. Conversely, a Trump White House may provide a more hostile and coercive environment for Sheinbaum to operate within.

Outlook

Given the current instability affecting the early stage of Claudia Sheinbaum’s administration, companies and investors need to adapt their current strategy to seize the right set of circumstances for their business.

Despite the undefined agenda for energy public policies and the ongoing debate between energy transition and oil investment, Sheinbaum will need to prioritise a stable domestic energy supply. Therefore, companies that want to be aligned with the government's agenda should invest in projects focused on new technologies that bolster domestic production or increase resilience.

Foreign companies may have concerns about the continuation of policies aligned with López Obrador’s approach, especially given the limited or even absent participation of private investment in Mexican oil companies in recent years. To mitigate this risk, companies can engage and promote public-private partnerships, which can foster joint ventures. However, joint ventures can present risk in the case of the nationalisation of foreign companies, but this is unlikely to occur under Sheinbaum’s presidency. Investors should focus on sectors that are likely to receive government support, such as technologies that enhance energy independence or generate a constant supply.

It is important to mention that there will be clearer indications if Sheinbaum will prioritise climate commitments or follow the steps of her predecessor in due course. Additionally, the outcome of the US elections is likely to significantly impact the country’s energy policy framework.

Australian Mining in Crisis: Nickel’s Price Plunge

On February 16th, Australia added nickel to its Critical Minerals List to protect its mining industry from strong competition from low-cost Indonesian nickel. Indonesia’s nickel industry is expected to continue growing, backed by pursuant investments from China. Australia’s inclusion of nickel makes the mineral eligible for a 3.9 billion-dollar fund to support the minerals industries linked to the energy transition through grants and loans with low-interest rates. This inclusion is a response to the persistent downward trend of nickel prices that began at the end of 2022, caused by an increase in the supply of cheaper nickel produced in Indonesia. Nickel is used to manufacture batteries for electrical vehicles (EVs) and stainless steel. However, the low-profit margin of nickel exploitation, in combination with increased competition from Indonesia, is jeopardising the Australian mining industry and pushing investors away from Australian mines.

Chinese Investment Into Indonesian Nickel And Its Impacts On Australia

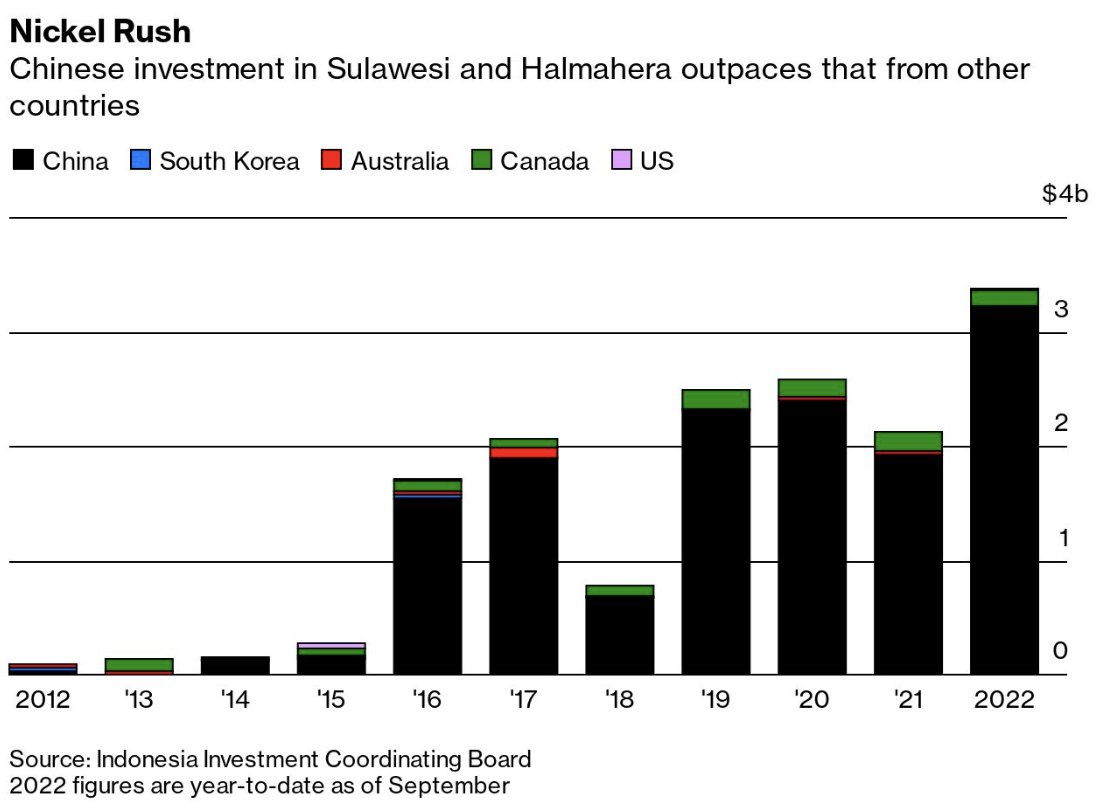

One of the biggest reasons for the global decline in nickel prices, which decreased by 45% in the past year, is Chinese investment in Indonesia. In 2020, Indonesia–which holds 42% of the global nickel reserves–reinstated a ban on unprocessed nickel exports to encourage onshore investment in its processing industry. Large multinational companies, such as Ford and Hyundai, invested in ore processing and manufacturing in the archipelago to access its nickel reserves. Indonesian lateritic nickel ore is attractive as it is closer to the surface than the sulphide ore found in Australia or Canada, making the required infrastructure to exploit it significantly cheaper. The sector received massive Chinese investments in various forms, such as refineries, smelters, and metallurgic schools, to develop the industry that had not previously evolved due to the lack of business know-how and financial investments. In 2022, Chinese investments accounted for 94.1% of the total foreign direct investments in the Indonesian reserves, as seen in the “Nickel Rush” chart below. The investments increased quickly after the ban on unprocessed Indonesian nickel in 2014, which was later eased. These investments boosted the production efficiency of Indonesian refined and semi-refined nickel, representing 55% of the world's total nickel supply in 2023 and potentially increasing its market share to 75% by 2030.

The chart can be found here.

The investment inflows towards Indonesian nickel also helped its laterite nickel ore to become more competitive compared to foreign ones. Primary nickel production is divided into two grades: (1) low-grade or Class II, which is used to manufacture stainless steel and found mainly in Indonesia, and (2) high-grade or Class I, which is used in batteries and can be found in Canada and Australia. While Indonesia has an abundant reserve of low-grade nickel, investments in the industry enabled its producers to apply sophisticated methods to upgrade its nickel to a higher grade. With the improved quality, this type of nickel can be used for batteries, after applying high temperature and pressure methods called high-pressure acid leaching (HPAL), allowing the Indonesian nickel to compete with other countries.

Global Challenges Impacting Nickel Demand

From the demand side, China, Europe, and the United States–Australia’s largest nickel importers—are simultaneously experiencing reduced demand for various reasons. The stainless steel market, which accounts for 75% of nickel use, was sluggish in 2023 due to a slow economic recovery in Europe and the US, which are still recovering from pre-COVID levels. Demand is set to increase by 8% in 2024, but the oversupply mutes its effects. As Sino-American tensions grow, China, the biggest EV market, faces deep and complex economic challenges, including a lack of trust from investors and buyers. Europe, the second biggest EV consumer, has seen the end of tax breaks and other government incentives to buy EVs. Moreover, the US’ high-interest rates prevent consumers from taking out loans, including for EV purchases. The combination of these factors is plummeting the aggregate demand for EVs, thus further pushing down nickel prices, an important mineral for EV batteries.

Consequently, Australian nickel mines are becoming uncompetitive at the current price range, with many even shutting down as nickel prices are expected to continue decreasing throughout 2024. The unit cost per ton of Australian nickel is 28% higher than in Indonesia. Also, while nickel prices decreased globally, its Australian production cost has increased by 49% since 2019, driven by rising wages. The London Metal Exchange (LME) listed nickel closed at US$16.356 per metric ton on February 16, a downward trend since its peak of around US$33,000 per metric ton in December 2022, as seen in the chart below. Companies such as IGO, First Quantum, and Wyloo Metals, some of the most prominent actors in Australian nickel mining, have pulled back investments or suspended part of their businesses.

Chart made by the author with data from Investing.com

These recent developments threaten the jobs of many Australian workers. BHP, the largest Australian mining company, recently announced it may take an impairment charge of around US$3.5 billion. The company plans to shut down its Nickel West division, which employs nearly 3,000 people. In total, the Australian nickel industry supported 10,000 jobs in 2023.

The situation is not exclusive to Australia. Eramet, a French mining company, lost 85% in revenue in 2023 in its New Caledonia nickel plant without any prospect of having government aid to increase its competitiveness. Macquarie, an asset management firm, estimates that 7% of the total nickel production has been removed due to closures. Even so, Australia will likely be the most affected. The country has 18% of global nickel reserves, but it is no longer competitive and is left contemplating the potential of its uncompetitive reserves.

The Debate Over 'Dirty' vs 'Clean' Nickel

There may be a solution to Australia’s nickel problem beyond access to the Australian Critical Mineral Facility Fund. Australian nickel producers are subjected to more strict sustainable standards than Indonesia, increasing costs. The refining of Australian nickel produces six times fewer emissions than other countries, including Indonesia. For these reasons, Madeleine King, the Australian Resources minister, urged the LME to split the listing of nickel into two categories: “dirty” coal-produced nickel and “clean” green nickel. Mining businessmen also demand this separation to motivate buyers to pay a premium for Australian and other nickel supplies with a smaller carbon footprint to level the competition against Indonesian nickel with this premium. This type of split in mineral contracts already exists, such as for aluminium and copper.

LME officials also declare that classifying minerals according to ESG criteria is a tough challenge given the lack of a universal ESG standard. Currently, carbon emissions per ton of the nickel listed in the LME vary greatly, from 6 to 100 tons of carbon dioxide per ton of nickel produced, and the lack of a standard makes it difficult to estimate the absolute emissions that would classify a nickel as “clean”. Currently, the LME classifies low-carbon nickel as producing less than 20 tons of carbon dioxide per ton, and it is working on a more precise definition with nickel specialists.

Reshaping the Australian nickel industry

It is unlikely that the LME will list green nickel separately from “dirty” nickel soon, given the liquidity threats this incurs. The broker wants to solidify buyers' confidence after the 2022 nickel episode before making changes that can jeopardise liquidity. LME officials stated in mid-March of this year that they have no plans to do so as the market size of a green nickel is not large enough to split it. On the other hand, Metalhub, a digital broker, recently started to split its nickel listing with the support of the LME. MetalHub allows the producers to have an ESG certificate tailored to their emissions per ton, which is more flexible than the LME ESG standards. The demand for the “clean” nickel in the digital broker would determine an index price used to derive the premium for this product type and delimit the liquidity of this trade contract. The digital broker plans to release the contract data when the volume traded increases.

It will be challenging to see nickel prices at levels that would make Australia's nickel mining industry competitive again. Indonesia is not hiding the fact that it wants to influence market prices with its nickel supply. According to Septian Hario Seto, an Indonesian deputy overseeing mining, the current price allows Indonesian nickel producers to sustain their activities. Also, low nickel prices will lower the costs of its emerging battery industry, completing the strategy to build an Indonesian upstream industry of batteries.

The access to Australia’s Critical Minerals Facility fund, in combination with the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) from the US, brings the expectation of an increase in investment towards the nickel industry. The Australian fund will be crucial to leverage projects to reduce costs by increasing productivity and infrastructure efficiency related to high costs such as energy, water, high-skilled labour, and transport. Also, the US’ IRA is set to increase the demand for Australian nickel, as it obliges US industries to purchase 40% of its critical minerals needs from either domestic producers or countries with which the US has a free trade agreement–wherein Australia is one of them. The two, combined with ever-evolving environmental regulations leading to a greater demand for EVs, can bring the required financial boost for Australia’s upstream nickel production. However, it will be more difficult for its nickel downstream industry given internal inflation and external competition not only from Indonesia but from all the countries building plans to rebuild their national processing industries.

When it comes to nickel buyers, assuming standard market incentives, they will pay more if they see an advantage in buying a cleaner metal, such as government subsidies or a bigger profit margin on selling a greener EV. Summing up, Australia chose to include nickel in its Critical Minerals List, assuming a big part of the responsibility to protect the industry. The government is one of the stakeholders with the financial ability and the incentive to avoid adverse socioeconomic developments. Minister King is also working with counterparts to advocate for robust standards in production to be reflected in a price premium. These counterparts–namely the US, the EU, and Canada–have the same interest in building an alternative supply chain to the Chinese one. The combination of factors such as the Critical Mineral Facility Fund, the IRA, and a possible stable price premium will give much-needed relief to persisting uncompetitive problems faced by Australian nickel producers. This seems to be the beginning of a pathway towards enhanced competitiveness for Australian nickel miners and, possibly, more sustainable nickel standards.

Even so, more funds might be insufficient to make the Australian nickel miners more competitive. Indonesia has a competitive advantage with a low production price that incurs high costs to its citizens. Coal mines are being constructed to fuel energy-intensive activities to upgrade the Indonesian nickel, making the country reach record levels of coal consumption and carbon emissions. Rivers are contaminated with heavy metals from the mines and refineries, exposing inadequate waste disposals. Addressing these environmental and social costs will level up Indonesian nickel prices, indirectly benefiting Australia and promising relief for the communities burdened by these impacts.

The LNG Freeze Limbo: How the US Export Pause is Reshaping Global Gas Dynamics

The Biden administration recently suspended granting permits for new liquified natural gas (LNG) imports, which will likely have major impacts on global energy security, especially for the European Union (EU). The move comes amidst growing protests against the Biden administration over its lacklustre plan to make a swift transition to green energy ecosystems. As per the White House, the decision aims to address domestic health concerns, such as increasing pollution near export facilities. However, the timing of the decision raises serious concerns, especially as the US’ European allies grapple with energy shortages since the Russian invasion of Ukraine 2 years ago.

The EU has been greatly dependent on LNG exports from the US in dealing with energy shortages following its decision to stop Russian exports. For instance, in the first half of 2023, the US exported more liquefied natural gas than any other country – 11.6 billion cubic feet a day. That same year, 60 per cent of US LNG exports were delivered to Europe and 46 per cent of European imports came from the US. This abrupt decision by President Biden, prioritising domestic concerns over international energy security and stability, is a long term challenge for US allies in Europe, as well as in Asia.

Despite the EU having fairly dealt with the energy shortages, a potentially long, harsh winter season later this year could further complicate the entire scenario, given the strong correlation between weather and gas prices. Winter conditions are, thus, likely to increase LNG demands, thereby increasing gas prices. Hence, shutting down gas exports to Europe is likely to accelerate geopolitical risks. This would imply diverting economic supply by the EU for Ukraine to deal with the impending energy crisis.

Many of the developing economies in Asia have traditionally been heavy consumers of coal and fossil fuels, primarily due to a lack of infrastructural capabilities to harness renewable sources of energy. Early LNG developments, especially in South East Asia were spurred on by the 1973 oil shock, which brought the need to diversify away from Middle Eastern oil for power generation. Consisting of many developing economies, countries in Asia wanted to rely on a stable and efficient partner to develop their energy ecosystems running on a fair share of LNG exports. Being the largest exporter of LNG in the world, the US was seen as “the reliable partner.” Hence, the recent announcement by the White House has been taken seriously in Asia, given that it might hinder the progress of capacity expansion projects in the region.

Moreover, one of the US’ strategic allies in the region, Japan, could be hit extremely hard by the recent development, given that it is the world’s second-largest purchaser of LNG, with a huge proportion of the imports coming from the United States. Several Japanese companies, especially JERA, have been foundation buyers of LNG export projects and this announcement is likely to hinder their business prospects in the present and the future. Moreover, the future implications of the pause are even more disastrous for the other allies of the US, especially smaller countries like the Philippines, which is currently undergoing energy shocks. The Philippines relies heavily on the electricity and natural gas acquired from the Malampaya gas field. This reserve is expected to run dry in 2027, causing an energy crisis. The nation must now choose between transitioning to renewable energy or continue to rely heavily on the exploration of conventional energy sources which would make them drift further apart from their commitments towards cutting down carbon emissions. The leadership in Manila initially looked to the United States to provide initial relief over its impending energy crisis by importing LNG reserves from the US. However, the latest White House decision will very well make the Philippines’ political leadership exhibit signs of perplexity and look for other alternatives as the Southeast Asian nation continues to grapple with an ongoing energy crisis which is likely to turn worse in the upcoming years.

While the decision might highlight the US’ decision to deal with environmental concerns and climate change issues, the abruptness of the decision is likely to raise serious doubts among the allies over Washington’s reliability to help them cope with the ongoing energy crisis, made worse by a sluggish global economy in the aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic. The move is likely to lead its partners to export LNG from other countries, which have a higher profile of emitting carbon emissions than the US.

This may also prompt countries to rely heavily on the use of coal and fossil fuels, thereby reversing the trend of actively exploring cleaner energy alternatives. With the global community facing an incoming climate emergency, substantial hope was placed on developed, industrialised countries of the north to create a strong base for the developing economies of the global south to make a transition towards cleaner energy ecosystems.

The US, with one of the largest reserves and the largest exporter of LNG, was seen as the “responsible leader” to effect this transition and, at the same time, stand shoulder to shoulder with struggling economies to deal with the contemporary energy shortage predicament. With ongoing geopolitical crises, the perception of the “pause” being indicative of breaking commitments to international partners and allies, cannot be undermined, in a year that is likely to decide the fate, political will, and the “ability to lead home and abroad amidst challenges” of the incumbent US president.

Featured image by Maciej Margas: PGNiG archive, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=90448259

M23: How a local armed rebel group in the DRC is altering the global mining sector

In recent weeks, North Kivu, a province in the eastern part of the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), has seen over 135,000 displacements in what has become the latest upsurge in a resurging conflict between the Congolese army and armed rebel groups. The indiscriminate bombing in the region puts an extra strain on the already-lacking humanitarian infrastructure in North Kivu, which thus far harbours approximately 2.5 million forcibly displaced people.

The March 23 Movement, or M23, is an armed rebel group that is threatening to take the strategic town of Sake, which is located a mere 27 kilometres west of North Kivu’s capital, Goma, a city of around two million people. In 2023, M23 became the most active non-state large actor in the DRC. Further advances will exacerbate regional humanitarian needs and could push millions more into displacement.

The role of minerals

Eastern Congo is a region that has been plagued with armed violence and mass killings for decades. Over 120 armed groups scramble for access to land, resources, and power. Central to the region, as well as the M23 conflict, is the DRC’s mining industry, which holds untapped deposits of raw minerals–estimated to be worth upwards of US$24 trillion. The recent increase in armed conflict in the region is likely to worsen the production output of the DRC’s mining sector, which accounts for 30 per cent of the country’s GDP and about 98 per cent of the country’s total exports.

The area wherein the wider Kivu Conflicts have unfolded in the last decade overlaps almost entirely with some of the DRC’s most valuable mineral deposits, as armed groups actively exploit these resources for further gain.

The artisanal and small-scale mining (ASM) sector produces about 90 per cent of the DRC’s mineral output. As the ASM sector typically lacks the size and security needed to efficiently deter influence from regional rebel groups, the mining sector as a whole falls victim to instability as a result of the M23 upsurge. Armed conflict and intervention by armed groups impacts 52 per cent of the mining sites in Eastern Congo, which manifests in the form of illegal taxation and extortion. As such, further acquisitions by M23 in Eastern Congo may put the DRC’s mineral sector under further strain.

The United Nations troop withdrawal

The escalation of the M23 conflict coincides with the United Nations’ plan to pull the entirety of their 13,500 peacekeeping troops out of the region by the end of the year upon the request of the recently re-elected government. With UN troops withdrawn, a military power vacuum is likely to form, thereby worsening insecurity and further damaging the DRC’s mining sector. However, regional armed groups are not the only actors that can clog this gap.

Regional international involvement

A further problem for the DRC’s mining sector is that the country’s political centre, Kinshasa, is located more than 1,600 km away from North Kivu, while Uganda and Rwanda share a border with the province.

Figure: Air travel distance between Goma and Kinshasa, Kigali and Kampala (image has been altered from the original)

The distance limits the government’s on-the-ground understanding of regional developments, including the extent of the involvement of armed groups in the ASM sector, thereby restricting the Congolese military’s effectiveness in countering regional rebellions.

In 2022, UN experts found ‘solid evidence’ that indicates that Rwanda is backing M23 fighters by aiding them with funding, training, and equipment provisions. Despite denials from both Kigali and M23 in explicit collaboration, Rwanda admitted to having military installments in eastern Congo. Rwanda claims that the installments act as a means to defend themselves from the Democratic Forces for the Liberation of Rwanda (FDLR)–an armed rebel group that Kigali asserts includes members who were complicit in the Rwandan genocide. The FDLR serves as a major threat to Kigali’s security, as its main stated aim is to overthrow the Rwandan government.

As such, M23, on the other hand, provides Rwanda with the opportunity to assert influence in the region and limit FDLR’s regional influence. Tensions between Rwanda and the DRC have, therefore, heightened, especially with the added fact that the Congolese army has provided FDLR with direct support to help the armed group fight against M23 rebels. As such, the DRC has been accused of utilising the FDLR as a proxy to counter Rwandan financial interests in the Congolese mining sector.

Another major point of contention between the states involves the smuggling of minerals. The DRC’s finance minister, Nicolas Kazadi, claimed Rwanda exported approximately $1bn in gold, as well as tin, tungsten, and tantalum (3T). The US Treasury has previously estimated that over 90 per cent of DRC’s gold is smuggled to neighbouring countries such as Uganda and Rwanda to undergo refinery processes before being exported, mainly to the UAE. Rwanda has repeatedly denied the allegations.

Furthermore, the tumultuous environment caused by the conflict might foster even weaker checks-and-balance systems, which will exacerbate corruption and mineral trafficking, which is already a serious issue regionally.

In previous surges of Congolese armed rebel violence, global demand for Congolese minerals plummeted, as companies sought to avoid problematic ‘conflict minerals’. In 2011, sales of tin ore from North Kivu decreased by 90 per cent in one month. Similar trends can be anticipated if the M23 rebellion gains strength, which may create a global market vacuum for other state’s exports to fill.

China

In recent years, China gained an economic stronghold of the DRC’s mining sector, as a vast majority of previously US-owned mines were sold off to China during the Obama and Trump administrations. It is estimated that Chinese companies control between 40 to 50 per cent of the DRC’s cobalt production alone. In an interest to protect its economic stakes, China sold nine CH-4 attack drones to the DRC back in February 2023, which the Congolese army utilised to curb the M23 expansion. Furthermore, Uganda has purchased Chinese arms, which it uses to carry out military operations inside of the DRC to counter the attacks of the Allied Democratic Forces (ADF), a Ugandan rebel group, which is based in the DRC. In return for military support, the DRC has granted China compensation via further access to its mining sector, which is helping bolster China’s mass production of electronics and technology within the green sector.

The US

Meanwhile, the US has put forth restrictions on imports of ‘conflict minerals’, which are minerals mined in conflict-ridden regions in DRC for the profit of armed groups. Although the US attempts to maintain certain levels of mineral trade with the DRC, the US’s influence in the country will likely continue to phase out and be overtaken by Beijing. The growing influence of M23 paves the path for further future collaboration between China and the DRC, both militarily and economically within the mining sector.

The UAE

The UAE, which is a major destination for smuggled minerals through Rwanda and Uganda, has since sought to end the illicit movement of Congolese precious metals via a joint venture that aims to export ‘fair gold’ directly from Congo to the UAE. In December of 2022, the UAE and DRC signed a 25-year contract over export rights for artisanally mined ores. The policy benefits both the DRC and the UAE as the UAE positions itself as a reliable partner in Kinshasa’s eyes, which paves the path for further business collaboration. In 2023, the UAE sealed a $1.9bn deal with a state-owned Congolese mining company in Congo that seeks to develop at least four mines in eastern DRC. The move can be interpreted as part of the UAE’s greater goal to increase its influence within the African mining sector.

Global Shifts

China and the UAE’s increasing involvement in the DRC can be seen as part of a greater diversification trend within the mining sector. Both states are particularly interested in securing a stronghold on the African mining sector, which can provide a steady and relatively cheap supply of precious metals needed to bolster the UAE’s and China’s renewables and vehicle production sectors. The scramble for control over minerals in Congo is part of the larger trend squeezing Western investment out of the African mining sector.

Furthermore, the UAE’s increasing influence in the DRC is representative of a larger trend of the Middle East gaining more traction as a rival to Chinese investment in Africa. Certain African leaders have even expressed interest in the Gulf states becoming the “New China” regionally, as Africa seeks alternatives to Western aid and Chinese loans.

Although Middle Eastern investment is far from overtaking China’s dominance of the global mining sector, an interest from Africa in diversifying their mining investor pools can go a long way in changing the investor share continentally. Furthermore, if the Middle East is to bolster its stance as a mining investor, Africa serves as a strategic starting point as China’s influence in the African mining sector is at times overstated. In 2018, China is estimated to have controlled less than 7 per cent of the value of total African mine production. Regardless, China’s strong grip on the global mining sector might be increasingly challenged through investor diversification in the African mining sector. The DRC is an informant of such a potential trend.

The further spread of the M23 rebellion, though likely to damage the Congolese mining business, might also foster stronger relations with countries such as the UAE which seek to minimise ‘conflict mineral’ imports. As such, the spread of the M23 rebellion–which acts as a breeding ground for smuggling, might catalyse new and stronger trade relations with the Middle East. This could be indicative of a trend of “de-Chinafication” in the region, or at least greater inter-regional competition for investment into the African mining sector.

A Strait Betwixt Two

As the Yemeni Houthi group's assault on maritime vessels continues to escalate, the risk to key commodity supply chains raises global concern. As analysed in this series' previous article (available here), conflict escalation impacts the region's security, impacting key trade routes and global trade patterns. The Suez Canal is a key trade route whose stability and security could impact and shift trade dynamics. As the search for alternative trade routes ensues, the Strait of Hormuz makes use of a power vacuum to expand its influence.

Suez Canal

The Suez Canal is a 193-kilometre waterway that connects the Red Sea to the Mediterranean Sea. Approximately 12% of global trade passes through the Canal, granting it vast economic, strategic, and geopolitical influence on a global scale. This canal shortens maritime trade routes between Asia and Europe by approximately 6,000 km by removing the need to export around the Cape of Good Hope and serves as a vital passage for oil shipments from the Persian Gulf to the West. Approximately 5.5 million barrels of oil a day pass through the Canal, making it a ‘competitor’ of the Strait of Hormuz.

Global trade via the Suez Canal is likely to decrease as a result of the rising tensions near the Bab el-Mandeb Strait. Due to their geographic predispositions, the Bab el-Mandeb Strait and the Suez Canal are interdependent; bottlenecks in either trade choke point will have a knock-on effect on the other. Bottlenecks caused by Houthi aggression against ships in the strait are likely to redirect maritime traffic from the Suez Canal to alternative passageways. From November to December 2023, the volume of shipping containers that passed through the Canal decreased from 500,000 to 200,000 per day, respectively, representing a reduction of 60%.

Suez Canal Trade Volume Differences (metric tonnes)

The overall trade volume in the Suez Canal has decreased drastically. Between October 7th, 2023, and February 25th, 2024, the channel’s trade volume decreased from 5,265,473 metric tonnes to 2,018,974 metric tonnes. As the weaponization of supply chains becomes part of regional economic power plays, there is a global interest in decreasing the vulnerability of vital choke points via trade route diversification. The lack of transport routes connecting Europe and Asia has hampered these interests, making choke points increasingly susceptible to exploitation.

Oil Trade Volumes in Millions of Barrels per Day in Vital Global Chokepoints

Source: Reuters

Quantitative Analysis

Many cargoes have been rerouted through the Cape of Good Hope to avoid the Red Sea region since the beginning of the Houthi conflict. Several European automakers announced reductions in operations due to delays in auto parts produced in Asia, demonstrating the high exposure of sectors dependent on imports from China.

In the first two weeks of 2024, cargo traffic decreased by 30% and tanker oil carriers by 19%. In contrast, transit around the Cape of Good Hope increased by 66% with cargoes and 65% by tankers in the same period. According to the analysis of JP Morgan economists, rerouting will increase transit times by 30% and reduce shipping capacities by 9%.

Depiction of Trade Route Diversion

Source: Al Jazeera

More fuel is used in the rerouted freight, an additional cost that increases the risk of cargo seizure and results in elevated shipping rates. The most affected routes were from Asia towards Europe, with 40% of their bilateral trade traversing the Red Sea. The freight rates of the north of Europe until the Far East, utilising the large ports of China and Singapore, have increased by 235% since mid-December; freights to the Mediterranean countries increased by 243%. Freights of products from China to the US spiked 140% two months into the conflict, from November 2023 to January 25, 2024. The OECD estimates that if the doubling of freight persists for a year, global inflation might rise to 0.4%.

The upward trend in freight rates can be seen in the graphic pictured below, depicting the “Shanghai Containerised Freight Index” (SCFI). The index represents the cost increase in times of crisis, such as at the beginning of the pandemic, when there were shipping and productive constraints, and more recently, with the Houthi rebel attacks. Most shipments through the Red Sea are container goods, accounting for 30% of the total global trade. Companies such as IKEA, Amazon, and Walmart use this route to deliver their Asian-made goods. As large corporations fear logistic and supply chain risk, more crucial trade volumes could be rerouted.

Shanghai Containerized Freight Index

Energy Commodity Impact

Of the commodities that traverse the Red Sea, oil and gas appear to be the most vulnerable. Before the attacks, 12% of the oil trade transited through the Red Sea, with a daily average of 8.2 million barrels. Most of this crude oil comes from the Middle East, destined for European markets, or from Russia, which sends 80% of its total oil exports to Chinese and Indian markets. The amount of oil from the Middle East remained robust in January. Saudi oil is being shipped from Muajjiz (already in the Red Sea) in order to avoid attack-hotspots in the strait of Bab al-Mandeb.

Iraq has been more cautious, contouring the Cape of Good Hope and increasing delays on its cargo. Iraq's oil imports to the region reached 500 thousand barrels per day (kbd) in February, 55% less than the previous year's daily average. Conversely, Iraq's oil imports increased in Asia, signalling a potential reshuffling of transport destinations. Trade with India reached a new high since April 2022 of 1.15 million barrels per day (mbd) in January 2024, a 26% increase from the daily average imports from Iraq's crude.

Brent Crude and WTI Crude Fluctuations

Source: Technopedia

Refined products were also impacted. Usually, 3.5 MBd were shipped via the Suez Canal in 2023, or around 14% of the total global flow. Nearly 15% of the global trade in Naphta passes through the Red Sea, amounting to 450 kbd. One of these cargoes was attacked, the Martin Luanda, laden with Russian naphtha, causing a 130 kbd reduction in January compared with the same month in 2023. Traffic to and from Europe is being diverted in light of the conflict. Jet fuel cargoes sent from India and the Middle East to Europe, amounting to 480 kbd, are avoiding the affected region, circling the Cape of Good Hope.

Due to these extra miles and higher speeds to counteract the delays, bunker fuel sales saw record highs in Singapore and the Middle East. The vessel must use more fuel, and bunker fuel demand increased by 12.1% in a year-over-year comparison in Singapore.

In 2023, eight percent, or 31.7 billion cubic metres (bcm), of the LNG trade traversed the Red Sea. The US and Qatar exports are the most prominent in the Red Sea. After sanctioning Russia's oil because of the Ukrainian War, Europe started to rely more on LNG shipments from the Middle East, mainly from Qatar. The country shipped 15 metric tonnes of LNG via the Red Sea to Europe, representing a share of 19% of the Qatari LNG exports. Vessels travelling to and from Qatar will have to circle the Cape of Good Hope, adding 10–11 days to travel times and negatively impacting cargo transit.

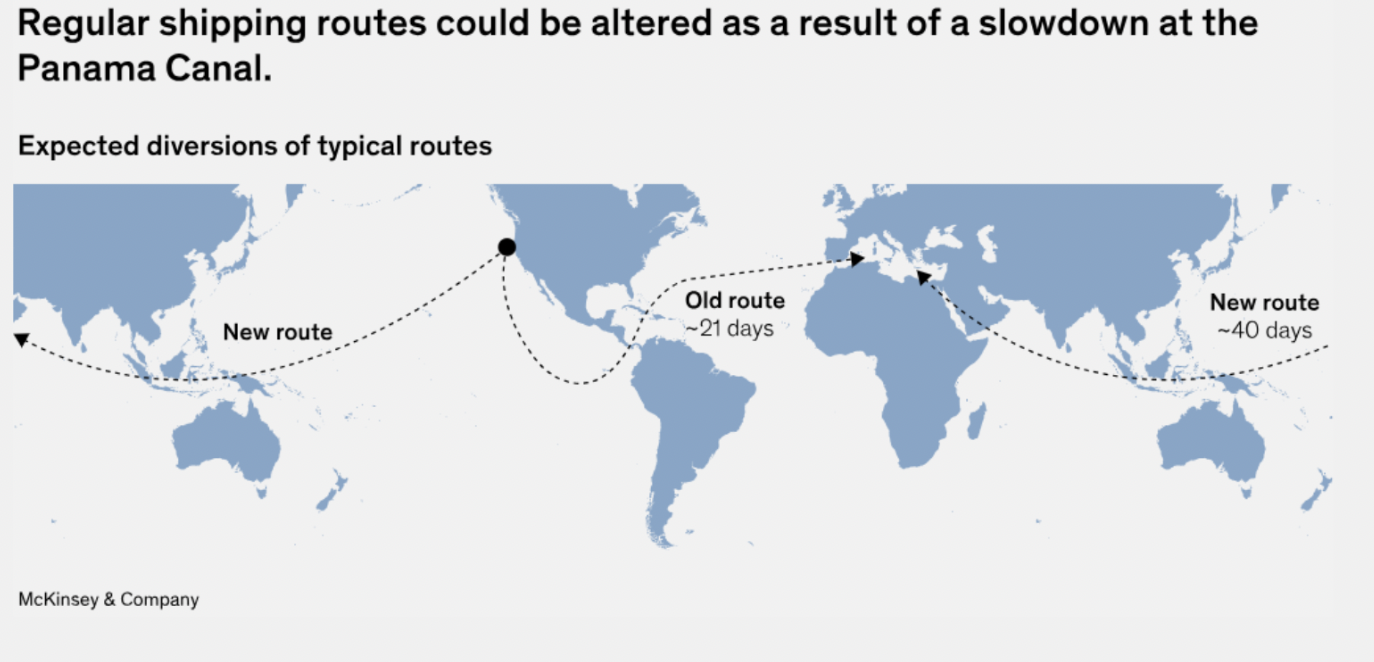

US LNG export capacity has increased in the past few years, sending shipments to Asia via the Red Sea. The Panama Canal receives many LNG cargoes from the US via the Pacific, yet its traffic limitations cause US cargo to be routed through the Atlantic and the Red Sea. The figure “Trade Shipping Routes” below displays the dimensions of the shifts that US LNG cargoes must take in the absence of passage via the Panama Canal.

Trade Shipping Routes

Source: McKinsey & Company

Until January 15, at least 30 LNG tankers were rerouted to pass through the Cape of Good Hope instead. Russia's LNG shipments to Asia are currently avoiding the Red Sea, and Qatar did not send any new shipments in the last fortnight of January after the Western strikes at Houthi targets.

Risk Assessment

A share of 12% of oil tankers, ships designed to carry oil, and 8% of liquified gas pass through this route towards the Mediterranean. Inventories in Europe are still high, but if the crisis persists for several months, energy prices could be aggravated. As evidenced by the sanctions against Russia, cargo reshuffling is possible. Qatar can send its cargoes to Asia, and those from the US can go to European markets, allowing suppliers to effectively avoid the Red Sea.

Around 12% of the seaborn grains traversed the Red Sea, representing monthly grain shipments of 7 megatonnes. The most considerable bulk are wheat and grain exports from the US, Europe, and the Black Sea. Around 4.5 million metric tonnes of grain shipments from December to February avoided the area, with a notable decrease of 40% in wheat exports. The attacks affected Robusta coffee cargoes as well. Cargoes from Vietnam, Indonesia, and India towards Europe were intercepted, impacting shipping prices and incentivizing trade with alternative nations.

Daily arrivals of bulk dry vessels, including iron ore and grain from Asia, were down by 45% on January 28, 2024, and container goods were down by 91%. However, further significant disruptions to agricultural exports are not expected. Most of the exports from the US, a large bulk, were passing through the Suez Canal to avoid the congestion of the Panama Canal due to the droughts that limited the capacity of circulation. These cargoes are now traversing the Cape route.

Around 320 million metric tonnes of bulk sail through Suez, or 7% of the world bulk trade. No significant impacts are predicted for iron ore or coal, which represented 42 and 99 megatonnes of volume, respectively, shipped through the Red Sea in 2023. Most of the dry bulks that traverse the impacted region can be purchased from other suppliers, precluding significant supply disruptions.

As of March 1st, reports show that only grain shipments and Iranian vessels were passing through the Red Sea. There were no oil or LNG shipments with non-Iranian links in the Red Sea. These developments illustrate the significant trade shifts caused by the Red Sea crisis. As of today, a looming threat lies in the Houthis’ promises of large-scale attacks during Ramadan. The lack of intelligence on the Houthi’s military capacity and power makes it difficult to ascertain the extent of future conflicts, generating further uncertainty in commercial trade.

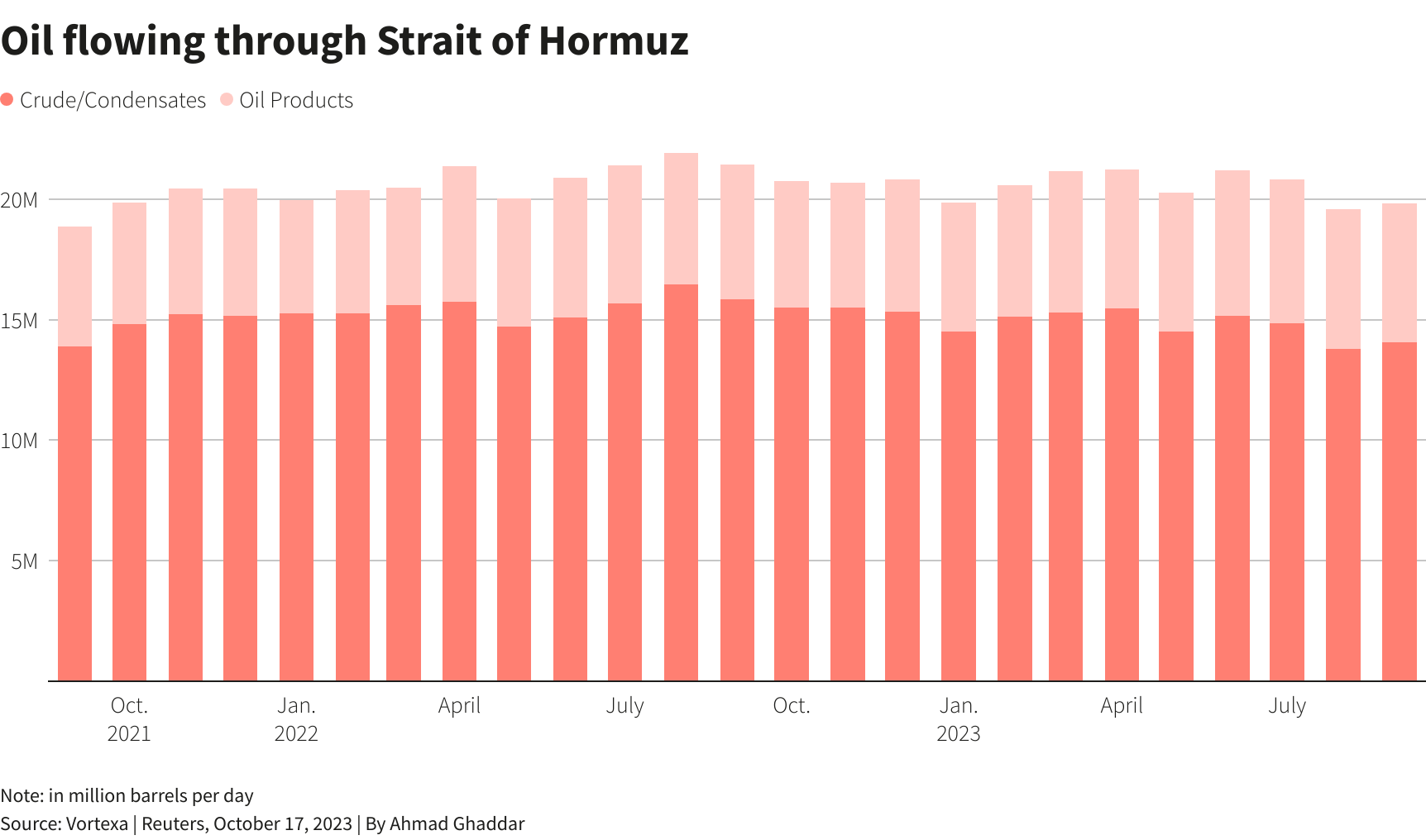

The Strait of Hormuz

The Strait of Hormuz is a channel that connects the Persian Gulf to the Gulf of Oman, providing Iran, Oman, and the UAE with access to maritime traffic and trade. The strait is estimated to carry about one-fifth of the global oil at a daily trade volume of 20.5 million barrels, proving to be of vital strategic importance for Middle Eastern oil supply the world’s largest oil transit chokepoint. The strait is a prominent trade corridor for a myriad of oil-exporting nations, namely the OPEC members Saudi Arabia, Iran, the UAE, Kuwait, and Iraq. These nations export most of their crude oil via the passage, with total volumes reaching 21 mb of crude oil daily, or 21% of total petroleum liquid products. Additionally, Qatar, the largest global exporter of LNG, exports most of its LNG via the Strait.

Geographic Location of Strait of Hormuz

Source: Marketwatch

Although the strait is technically regulated by the 1982 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, Iran has not ratified the agreement. Through its geostrategic placement, Iran can trigger oil price responses through its influence on trade transit, establishing the country’s regional and global influence.

Strait of Hormuz Oil Volumes

Source: Reuters

Experts are particularly worried that the turbulence is likely to spread to the Strait of Hormuz now that Iran backs the Houthis in Yemen and might want to support their cause by doubling down regionally. However, this is something that would cause a lot of backlash in the form of a further tightening of economic sanctions against Tehran, which might deter further provocations.

Despite Iran’s previous threats to block the Strait entirely, these have never gone into effect. Diversifying trade routes to avoid supply shocks and bottlenecks is of interest to regional oil-exporters dependent on the route for maritime trade access. Such diversification attempts have already been undertaken, as seen by the UAE and Saudi Arabia's attempts to bypass the Strait of Hormuz through the construction of alternative oil pipelines. The loss of trade volume from these two producers, holding the world's second and fifth largest oil reserves, respectively, severely hindered the corridor’s prominence.

The attacks on the Red Sea might cause damage to the oil and LNG cargo from countries in the Persian Gulf, increasing costs for oil and gas exporters. However, cargoes could find alternative destinations. The vast Asian markets, which face a shortage of energy products due to a loss of trade through the Red Sea, could be a potential suitor. Finding new LPG (liquefied petroleum gas) contracts could be beneficial for Iran, and its recently enhanced production capacity could supply various markets.

Geopolitics and Prospects for a Route Shift

Although the Strait of Hormuz stands to capture diverted trade flows from the Suez Canal, its global influence is still limited by Iran’s geopolitical ties. As exemplified by the Iran-US conflict, Iran’s conflicts can severely impact traffic through the Strait, significantly impacting the stability of the route and prospects for future growth.

Although security and stability are of paramount importance to trade, efforts to provide these traits could be counterproductive. On March 12th, China and Russia conducted maritime drills and exercises in the Gulf of Oman with naval and aviation vessels. According to Russia's Ministry of Defence, this five-day exercise sought to enhance the security of maritime economic activities using maritime vessels with anti-ship missiles and advanced defence systems. Over 20 vessels were displayed in this joint naval drill, attempting to lure trade through the promise of stability and security.

Whether meant as a display of power or a promise of security, the pronounced presence of Russian and Chinese forces could aggravate geopolitical tensions and increase the potential for conflict in the region, driving global trade prospects down. With precedents of trade conflict, such as the IRGC’s seizure of an American oil cargo in the Persian Gulf on January 22nd, various countries might be sceptical of rerouting commodity trade through the Strait.

Tensions are also aggravated by Iran’s alleged assistance in the Houthi attacks. The US has supposedly communicated indirectly with Iran to urge them to intervene in the region. China and Russia’s interest in improving the Strait’s trade prospects would benefit from a de-escalation of the Houthi conflict, as shown by China’s insistence on Iran’s cooperation in the Houthi conflict. As the conflict stands, the Strait’s prospect as an alternative trade route is dependent not only on Iran’s reputation and presence in global conflicts but also on the route’s patrons and proponents.

Conclusion

The extent to which the Strait of Hormuz could benefit from trade diversion depends not only on its ability to pose itself as a viable trade route but also on the duration of the Houthi conflict. In order to capture trade volumes and increase international trade through the route, Iran would have to ameliorate its geopolitical ties and provide stability to compete with rising prospective trade route alternatives. Although the conflict in the Suez has yet to show promising signs of de-escalation, securing the Suez would likely cause previous trade volumes to resume and restore its hegemony in commodity trade. It remains to be seen whether the conflict will endure long enough to allow other trade routes to be established as alternatives and permanently shift power balances in global trade.

The U.S. LNG Pause: Implications for the Global Fertiliser and Food Markets

Peter Fawley

The U.S. LNG Pause

On January 26, the Biden administration announced a temporary pause on approvals of new liquified natural gas (LNG) export projects. The pause applies to proposed or future projects that have not yet received authorisation from the United States (U.S.) Department of Energy (DOE) to export LNG to countries that do not have a free trade agreement (FTA) with the United States. This is significant as many of the largest importers of U.S. LNG–including members of the European Union, the United Kingdom, Japan, and China–do not have FTAs with the United States. Without the DOE authorisation, an LNG project will not be allowed to export to these countries. The policy will not affect existing export projects or those currently under construction. The Department of Energy has not offered any indication for how long the pause will be in effect.

This pause will have political and economic implications across the globe, and is expected to apply further pressure to the LNG market, fertiliser prices, and agricultural production. The following analysis will first delve into the rationale for the pause, the expected impact it will have on global LNG supplies, and the associated risks this poses for the fertiliser and food markets. It will then examine the impact of this policy change on India’s agricultural sector, given that the country is heavily reliant on LNG imports to manufacture fertilisers for agricultural production. The article will conclude with brief remarks about the pause.

Reasons for the Pause

According to the Biden administration, the current review framework is outdated and does not properly account for the contemporary LNG market. The White House’s announcement cited issues related to the consideration of energy costs and environmental impacts. The pause will allow DOE to update the underlying analysis and review process for LNG export authorisations to ensure that they more adequately account for current considerations and are aligned with the public interest.

There are also likely political motivations at play, given the upcoming election in the United States. Both climate considerations and domestic energy prices are expected to garner significant attention during the lead up to the 2024 U.S. presidential election. The Biden administration has been under increasing pressure from environmental activists, the political left, and domestic industry regarding the U.S. LNG industry’s impact on climate goals and domestic energy prices. In fact, over 60 U.S policymakers recently sent a letter to DOE urging its leadership to reexamine how it factors in public interests when authorising new licences for LNG export projects.

These groups have argued that the stark increase in recent U.S. LNG exports is incompatible with U.S. climate commitments and policy objectives, as the LNG value chain has a sizeable emissions footprint. Moreover, there is a concern about the standard it sets for future policy. An implicit and uncontested acceptance of LNG could signal that the U.S is wholly committed to continued use of fossil fuels as an energy source, leading to more industry investments in fossil fuels at the expense of renewable energy technologies. In an unusual political alliance, large U.S. industrial manufacturers are lobbying alongside environmentalists to curb LNG exports. These consumers, who are dependent on natural gas for their manufacturing processes, worry that additional LNG export projects will raise domestic natural gas prices. Therefore, the pause may then be interpreted as an acknowledgement of these concerns and an attempt to reassure supporters that the Biden administration is committed to furthering its climate goals and securing lower domestic energy prices.

Impact on LNG Supplies

Since the pause only pertains to prospective projects, there will be no impact on current U.S. LNG export capacity. However, the pause may constrain supply and reduce forecasted global output as the new policy indefinitely halts progress on proposed LNG projects that are currently awaiting DOE authorisation. In the long-term, this announcement has the potential to tighten the LNG market, potentially resulting in increased natural gas prices and other commercial ramifications. Because the U.S. is currently the world’s largest LNG exporter, a drop in expected future U.S. supplies may force LNG importers to seek to diversify their supply. Some LNG buyers will likely redirect their attention to other, more certain sources of LNG, such as Qatar or Australia. Additionally, industry may be more keen to invest in projects in countries that have less regulatory ambiguity related to LNG projects.

Risk for the Global Fertiliser and Food Markets