Australian Mining in Crisis: Nickel’s Price Plunge

On February 16th, Australia added nickel to its Critical Minerals List to protect its mining industry from strong competition from low-cost Indonesian nickel. Indonesia’s nickel industry is expected to continue growing, backed by pursuant investments from China. Australia’s inclusion of nickel makes the mineral eligible for a 3.9 billion-dollar fund to support the minerals industries linked to the energy transition through grants and loans with low-interest rates. This inclusion is a response to the persistent downward trend of nickel prices that began at the end of 2022, caused by an increase in the supply of cheaper nickel produced in Indonesia. Nickel is used to manufacture batteries for electrical vehicles (EVs) and stainless steel. However, the low-profit margin of nickel exploitation, in combination with increased competition from Indonesia, is jeopardising the Australian mining industry and pushing investors away from Australian mines.

Chinese Investment Into Indonesian Nickel And Its Impacts On Australia

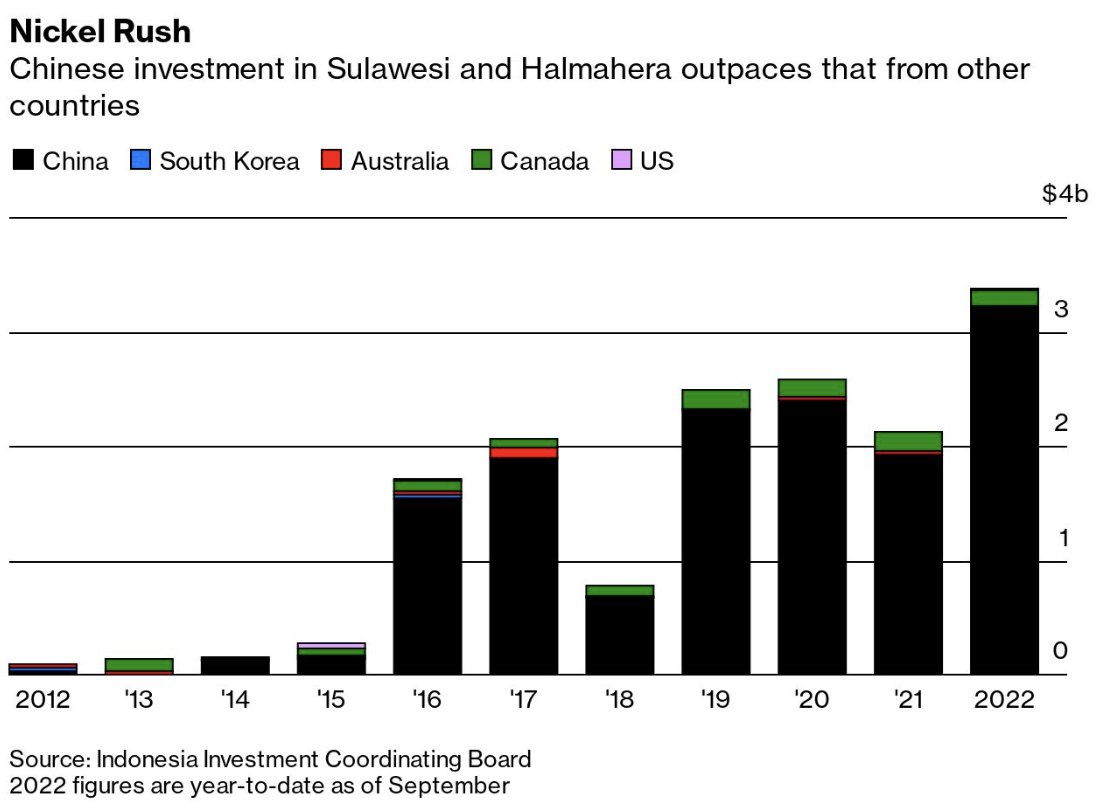

One of the biggest reasons for the global decline in nickel prices, which decreased by 45% in the past year, is Chinese investment in Indonesia. In 2020, Indonesia–which holds 42% of the global nickel reserves–reinstated a ban on unprocessed nickel exports to encourage onshore investment in its processing industry. Large multinational companies, such as Ford and Hyundai, invested in ore processing and manufacturing in the archipelago to access its nickel reserves. Indonesian lateritic nickel ore is attractive as it is closer to the surface than the sulphide ore found in Australia or Canada, making the required infrastructure to exploit it significantly cheaper. The sector received massive Chinese investments in various forms, such as refineries, smelters, and metallurgic schools, to develop the industry that had not previously evolved due to the lack of business know-how and financial investments. In 2022, Chinese investments accounted for 94.1% of the total foreign direct investments in the Indonesian reserves, as seen in the “Nickel Rush” chart below. The investments increased quickly after the ban on unprocessed Indonesian nickel in 2014, which was later eased. These investments boosted the production efficiency of Indonesian refined and semi-refined nickel, representing 55% of the world's total nickel supply in 2023 and potentially increasing its market share to 75% by 2030.

The chart can be found here.

The investment inflows towards Indonesian nickel also helped its laterite nickel ore to become more competitive compared to foreign ones. Primary nickel production is divided into two grades: (1) low-grade or Class II, which is used to manufacture stainless steel and found mainly in Indonesia, and (2) high-grade or Class I, which is used in batteries and can be found in Canada and Australia. While Indonesia has an abundant reserve of low-grade nickel, investments in the industry enabled its producers to apply sophisticated methods to upgrade its nickel to a higher grade. With the improved quality, this type of nickel can be used for batteries, after applying high temperature and pressure methods called high-pressure acid leaching (HPAL), allowing the Indonesian nickel to compete with other countries.

Global Challenges Impacting Nickel Demand

From the demand side, China, Europe, and the United States–Australia’s largest nickel importers—are simultaneously experiencing reduced demand for various reasons. The stainless steel market, which accounts for 75% of nickel use, was sluggish in 2023 due to a slow economic recovery in Europe and the US, which are still recovering from pre-COVID levels. Demand is set to increase by 8% in 2024, but the oversupply mutes its effects. As Sino-American tensions grow, China, the biggest EV market, faces deep and complex economic challenges, including a lack of trust from investors and buyers. Europe, the second biggest EV consumer, has seen the end of tax breaks and other government incentives to buy EVs. Moreover, the US’ high-interest rates prevent consumers from taking out loans, including for EV purchases. The combination of these factors is plummeting the aggregate demand for EVs, thus further pushing down nickel prices, an important mineral for EV batteries.

Consequently, Australian nickel mines are becoming uncompetitive at the current price range, with many even shutting down as nickel prices are expected to continue decreasing throughout 2024. The unit cost per ton of Australian nickel is 28% higher than in Indonesia. Also, while nickel prices decreased globally, its Australian production cost has increased by 49% since 2019, driven by rising wages. The London Metal Exchange (LME) listed nickel closed at US$16.356 per metric ton on February 16, a downward trend since its peak of around US$33,000 per metric ton in December 2022, as seen in the chart below. Companies such as IGO, First Quantum, and Wyloo Metals, some of the most prominent actors in Australian nickel mining, have pulled back investments or suspended part of their businesses.

Chart made by the author with data from Investing.com

These recent developments threaten the jobs of many Australian workers. BHP, the largest Australian mining company, recently announced it may take an impairment charge of around US$3.5 billion. The company plans to shut down its Nickel West division, which employs nearly 3,000 people. In total, the Australian nickel industry supported 10,000 jobs in 2023.

The situation is not exclusive to Australia. Eramet, a French mining company, lost 85% in revenue in 2023 in its New Caledonia nickel plant without any prospect of having government aid to increase its competitiveness. Macquarie, an asset management firm, estimates that 7% of the total nickel production has been removed due to closures. Even so, Australia will likely be the most affected. The country has 18% of global nickel reserves, but it is no longer competitive and is left contemplating the potential of its uncompetitive reserves.

The Debate Over 'Dirty' vs 'Clean' Nickel

There may be a solution to Australia’s nickel problem beyond access to the Australian Critical Mineral Facility Fund. Australian nickel producers are subjected to more strict sustainable standards than Indonesia, increasing costs. The refining of Australian nickel produces six times fewer emissions than other countries, including Indonesia. For these reasons, Madeleine King, the Australian Resources minister, urged the LME to split the listing of nickel into two categories: “dirty” coal-produced nickel and “clean” green nickel. Mining businessmen also demand this separation to motivate buyers to pay a premium for Australian and other nickel supplies with a smaller carbon footprint to level the competition against Indonesian nickel with this premium. This type of split in mineral contracts already exists, such as for aluminium and copper.

LME officials also declare that classifying minerals according to ESG criteria is a tough challenge given the lack of a universal ESG standard. Currently, carbon emissions per ton of the nickel listed in the LME vary greatly, from 6 to 100 tons of carbon dioxide per ton of nickel produced, and the lack of a standard makes it difficult to estimate the absolute emissions that would classify a nickel as “clean”. Currently, the LME classifies low-carbon nickel as producing less than 20 tons of carbon dioxide per ton, and it is working on a more precise definition with nickel specialists.

Reshaping the Australian nickel industry

It is unlikely that the LME will list green nickel separately from “dirty” nickel soon, given the liquidity threats this incurs. The broker wants to solidify buyers' confidence after the 2022 nickel episode before making changes that can jeopardise liquidity. LME officials stated in mid-March of this year that they have no plans to do so as the market size of a green nickel is not large enough to split it. On the other hand, Metalhub, a digital broker, recently started to split its nickel listing with the support of the LME. MetalHub allows the producers to have an ESG certificate tailored to their emissions per ton, which is more flexible than the LME ESG standards. The demand for the “clean” nickel in the digital broker would determine an index price used to derive the premium for this product type and delimit the liquidity of this trade contract. The digital broker plans to release the contract data when the volume traded increases.

It will be challenging to see nickel prices at levels that would make Australia's nickel mining industry competitive again. Indonesia is not hiding the fact that it wants to influence market prices with its nickel supply. According to Septian Hario Seto, an Indonesian deputy overseeing mining, the current price allows Indonesian nickel producers to sustain their activities. Also, low nickel prices will lower the costs of its emerging battery industry, completing the strategy to build an Indonesian upstream industry of batteries.

The access to Australia’s Critical Minerals Facility fund, in combination with the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) from the US, brings the expectation of an increase in investment towards the nickel industry. The Australian fund will be crucial to leverage projects to reduce costs by increasing productivity and infrastructure efficiency related to high costs such as energy, water, high-skilled labour, and transport. Also, the US’ IRA is set to increase the demand for Australian nickel, as it obliges US industries to purchase 40% of its critical minerals needs from either domestic producers or countries with which the US has a free trade agreement–wherein Australia is one of them. The two, combined with ever-evolving environmental regulations leading to a greater demand for EVs, can bring the required financial boost for Australia’s upstream nickel production. However, it will be more difficult for its nickel downstream industry given internal inflation and external competition not only from Indonesia but from all the countries building plans to rebuild their national processing industries.

When it comes to nickel buyers, assuming standard market incentives, they will pay more if they see an advantage in buying a cleaner metal, such as government subsidies or a bigger profit margin on selling a greener EV. Summing up, Australia chose to include nickel in its Critical Minerals List, assuming a big part of the responsibility to protect the industry. The government is one of the stakeholders with the financial ability and the incentive to avoid adverse socioeconomic developments. Minister King is also working with counterparts to advocate for robust standards in production to be reflected in a price premium. These counterparts–namely the US, the EU, and Canada–have the same interest in building an alternative supply chain to the Chinese one. The combination of factors such as the Critical Mineral Facility Fund, the IRA, and a possible stable price premium will give much-needed relief to persisting uncompetitive problems faced by Australian nickel producers. This seems to be the beginning of a pathway towards enhanced competitiveness for Australian nickel miners and, possibly, more sustainable nickel standards.

Even so, more funds might be insufficient to make the Australian nickel miners more competitive. Indonesia has a competitive advantage with a low production price that incurs high costs to its citizens. Coal mines are being constructed to fuel energy-intensive activities to upgrade the Indonesian nickel, making the country reach record levels of coal consumption and carbon emissions. Rivers are contaminated with heavy metals from the mines and refineries, exposing inadequate waste disposals. Addressing these environmental and social costs will level up Indonesian nickel prices, indirectly benefiting Australia and promising relief for the communities burdened by these impacts.