Australian Mining in Crisis: Nickel’s Price Plunge

On February 16th, Australia added nickel to its Critical Minerals List to protect its mining industry from strong competition from low-cost Indonesian nickel. Indonesia’s nickel industry is expected to continue growing, backed by pursuant investments from China. Australia’s inclusion of nickel makes the mineral eligible for a 3.9 billion-dollar fund to support the minerals industries linked to the energy transition through grants and loans with low-interest rates. This inclusion is a response to the persistent downward trend of nickel prices that began at the end of 2022, caused by an increase in the supply of cheaper nickel produced in Indonesia. Nickel is used to manufacture batteries for electrical vehicles (EVs) and stainless steel. However, the low-profit margin of nickel exploitation, in combination with increased competition from Indonesia, is jeopardising the Australian mining industry and pushing investors away from Australian mines.

Chinese Investment Into Indonesian Nickel And Its Impacts On Australia

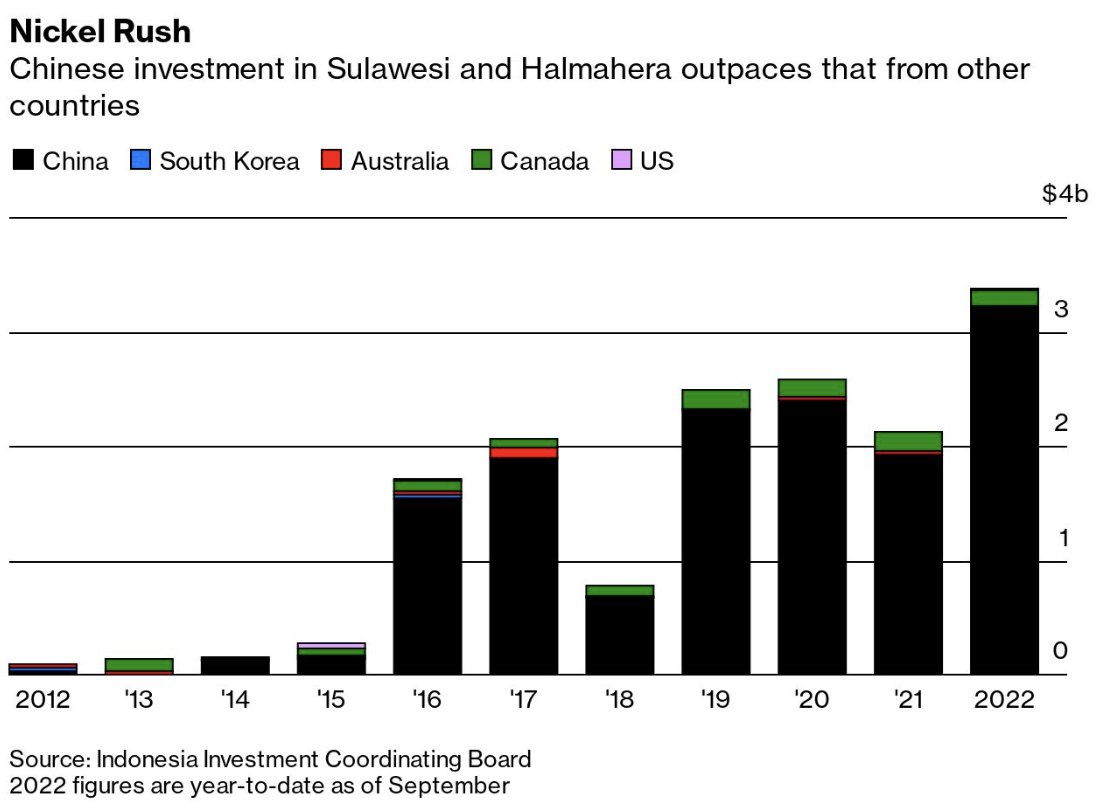

One of the biggest reasons for the global decline in nickel prices, which decreased by 45% in the past year, is Chinese investment in Indonesia. In 2020, Indonesia–which holds 42% of the global nickel reserves–reinstated a ban on unprocessed nickel exports to encourage onshore investment in its processing industry. Large multinational companies, such as Ford and Hyundai, invested in ore processing and manufacturing in the archipelago to access its nickel reserves. Indonesian lateritic nickel ore is attractive as it is closer to the surface than the sulphide ore found in Australia or Canada, making the required infrastructure to exploit it significantly cheaper. The sector received massive Chinese investments in various forms, such as refineries, smelters, and metallurgic schools, to develop the industry that had not previously evolved due to the lack of business know-how and financial investments. In 2022, Chinese investments accounted for 94.1% of the total foreign direct investments in the Indonesian reserves, as seen in the “Nickel Rush” chart below. The investments increased quickly after the ban on unprocessed Indonesian nickel in 2014, which was later eased. These investments boosted the production efficiency of Indonesian refined and semi-refined nickel, representing 55% of the world's total nickel supply in 2023 and potentially increasing its market share to 75% by 2030.

The chart can be found here.

The investment inflows towards Indonesian nickel also helped its laterite nickel ore to become more competitive compared to foreign ones. Primary nickel production is divided into two grades: (1) low-grade or Class II, which is used to manufacture stainless steel and found mainly in Indonesia, and (2) high-grade or Class I, which is used in batteries and can be found in Canada and Australia. While Indonesia has an abundant reserve of low-grade nickel, investments in the industry enabled its producers to apply sophisticated methods to upgrade its nickel to a higher grade. With the improved quality, this type of nickel can be used for batteries, after applying high temperature and pressure methods called high-pressure acid leaching (HPAL), allowing the Indonesian nickel to compete with other countries.

Global Challenges Impacting Nickel Demand

From the demand side, China, Europe, and the United States–Australia’s largest nickel importers—are simultaneously experiencing reduced demand for various reasons. The stainless steel market, which accounts for 75% of nickel use, was sluggish in 2023 due to a slow economic recovery in Europe and the US, which are still recovering from pre-COVID levels. Demand is set to increase by 8% in 2024, but the oversupply mutes its effects. As Sino-American tensions grow, China, the biggest EV market, faces deep and complex economic challenges, including a lack of trust from investors and buyers. Europe, the second biggest EV consumer, has seen the end of tax breaks and other government incentives to buy EVs. Moreover, the US’ high-interest rates prevent consumers from taking out loans, including for EV purchases. The combination of these factors is plummeting the aggregate demand for EVs, thus further pushing down nickel prices, an important mineral for EV batteries.

Consequently, Australian nickel mines are becoming uncompetitive at the current price range, with many even shutting down as nickel prices are expected to continue decreasing throughout 2024. The unit cost per ton of Australian nickel is 28% higher than in Indonesia. Also, while nickel prices decreased globally, its Australian production cost has increased by 49% since 2019, driven by rising wages. The London Metal Exchange (LME) listed nickel closed at US$16.356 per metric ton on February 16, a downward trend since its peak of around US$33,000 per metric ton in December 2022, as seen in the chart below. Companies such as IGO, First Quantum, and Wyloo Metals, some of the most prominent actors in Australian nickel mining, have pulled back investments or suspended part of their businesses.

Chart made by the author with data from Investing.com

These recent developments threaten the jobs of many Australian workers. BHP, the largest Australian mining company, recently announced it may take an impairment charge of around US$3.5 billion. The company plans to shut down its Nickel West division, which employs nearly 3,000 people. In total, the Australian nickel industry supported 10,000 jobs in 2023.

The situation is not exclusive to Australia. Eramet, a French mining company, lost 85% in revenue in 2023 in its New Caledonia nickel plant without any prospect of having government aid to increase its competitiveness. Macquarie, an asset management firm, estimates that 7% of the total nickel production has been removed due to closures. Even so, Australia will likely be the most affected. The country has 18% of global nickel reserves, but it is no longer competitive and is left contemplating the potential of its uncompetitive reserves.

The Debate Over 'Dirty' vs 'Clean' Nickel

There may be a solution to Australia’s nickel problem beyond access to the Australian Critical Mineral Facility Fund. Australian nickel producers are subjected to more strict sustainable standards than Indonesia, increasing costs. The refining of Australian nickel produces six times fewer emissions than other countries, including Indonesia. For these reasons, Madeleine King, the Australian Resources minister, urged the LME to split the listing of nickel into two categories: “dirty” coal-produced nickel and “clean” green nickel. Mining businessmen also demand this separation to motivate buyers to pay a premium for Australian and other nickel supplies with a smaller carbon footprint to level the competition against Indonesian nickel with this premium. This type of split in mineral contracts already exists, such as for aluminium and copper.

LME officials also declare that classifying minerals according to ESG criteria is a tough challenge given the lack of a universal ESG standard. Currently, carbon emissions per ton of the nickel listed in the LME vary greatly, from 6 to 100 tons of carbon dioxide per ton of nickel produced, and the lack of a standard makes it difficult to estimate the absolute emissions that would classify a nickel as “clean”. Currently, the LME classifies low-carbon nickel as producing less than 20 tons of carbon dioxide per ton, and it is working on a more precise definition with nickel specialists.

Reshaping the Australian nickel industry

It is unlikely that the LME will list green nickel separately from “dirty” nickel soon, given the liquidity threats this incurs. The broker wants to solidify buyers' confidence after the 2022 nickel episode before making changes that can jeopardise liquidity. LME officials stated in mid-March of this year that they have no plans to do so as the market size of a green nickel is not large enough to split it. On the other hand, Metalhub, a digital broker, recently started to split its nickel listing with the support of the LME. MetalHub allows the producers to have an ESG certificate tailored to their emissions per ton, which is more flexible than the LME ESG standards. The demand for the “clean” nickel in the digital broker would determine an index price used to derive the premium for this product type and delimit the liquidity of this trade contract. The digital broker plans to release the contract data when the volume traded increases.

It will be challenging to see nickel prices at levels that would make Australia's nickel mining industry competitive again. Indonesia is not hiding the fact that it wants to influence market prices with its nickel supply. According to Septian Hario Seto, an Indonesian deputy overseeing mining, the current price allows Indonesian nickel producers to sustain their activities. Also, low nickel prices will lower the costs of its emerging battery industry, completing the strategy to build an Indonesian upstream industry of batteries.

The access to Australia’s Critical Minerals Facility fund, in combination with the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) from the US, brings the expectation of an increase in investment towards the nickel industry. The Australian fund will be crucial to leverage projects to reduce costs by increasing productivity and infrastructure efficiency related to high costs such as energy, water, high-skilled labour, and transport. Also, the US’ IRA is set to increase the demand for Australian nickel, as it obliges US industries to purchase 40% of its critical minerals needs from either domestic producers or countries with which the US has a free trade agreement–wherein Australia is one of them. The two, combined with ever-evolving environmental regulations leading to a greater demand for EVs, can bring the required financial boost for Australia’s upstream nickel production. However, it will be more difficult for its nickel downstream industry given internal inflation and external competition not only from Indonesia but from all the countries building plans to rebuild their national processing industries.

When it comes to nickel buyers, assuming standard market incentives, they will pay more if they see an advantage in buying a cleaner metal, such as government subsidies or a bigger profit margin on selling a greener EV. Summing up, Australia chose to include nickel in its Critical Minerals List, assuming a big part of the responsibility to protect the industry. The government is one of the stakeholders with the financial ability and the incentive to avoid adverse socioeconomic developments. Minister King is also working with counterparts to advocate for robust standards in production to be reflected in a price premium. These counterparts–namely the US, the EU, and Canada–have the same interest in building an alternative supply chain to the Chinese one. The combination of factors such as the Critical Mineral Facility Fund, the IRA, and a possible stable price premium will give much-needed relief to persisting uncompetitive problems faced by Australian nickel producers. This seems to be the beginning of a pathway towards enhanced competitiveness for Australian nickel miners and, possibly, more sustainable nickel standards.

Even so, more funds might be insufficient to make the Australian nickel miners more competitive. Indonesia has a competitive advantage with a low production price that incurs high costs to its citizens. Coal mines are being constructed to fuel energy-intensive activities to upgrade the Indonesian nickel, making the country reach record levels of coal consumption and carbon emissions. Rivers are contaminated with heavy metals from the mines and refineries, exposing inadequate waste disposals. Addressing these environmental and social costs will level up Indonesian nickel prices, indirectly benefiting Australia and promising relief for the communities burdened by these impacts.

M23: How a local armed rebel group in the DRC is altering the global mining sector

In recent weeks, North Kivu, a province in the eastern part of the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), has seen over 135,000 displacements in what has become the latest upsurge in a resurging conflict between the Congolese army and armed rebel groups. The indiscriminate bombing in the region puts an extra strain on the already-lacking humanitarian infrastructure in North Kivu, which thus far harbours approximately 2.5 million forcibly displaced people.

The March 23 Movement, or M23, is an armed rebel group that is threatening to take the strategic town of Sake, which is located a mere 27 kilometres west of North Kivu’s capital, Goma, a city of around two million people. In 2023, M23 became the most active non-state large actor in the DRC. Further advances will exacerbate regional humanitarian needs and could push millions more into displacement.

The role of minerals

Eastern Congo is a region that has been plagued with armed violence and mass killings for decades. Over 120 armed groups scramble for access to land, resources, and power. Central to the region, as well as the M23 conflict, is the DRC’s mining industry, which holds untapped deposits of raw minerals–estimated to be worth upwards of US$24 trillion. The recent increase in armed conflict in the region is likely to worsen the production output of the DRC’s mining sector, which accounts for 30 per cent of the country’s GDP and about 98 per cent of the country’s total exports.

The area wherein the wider Kivu Conflicts have unfolded in the last decade overlaps almost entirely with some of the DRC’s most valuable mineral deposits, as armed groups actively exploit these resources for further gain.

The artisanal and small-scale mining (ASM) sector produces about 90 per cent of the DRC’s mineral output. As the ASM sector typically lacks the size and security needed to efficiently deter influence from regional rebel groups, the mining sector as a whole falls victim to instability as a result of the M23 upsurge. Armed conflict and intervention by armed groups impacts 52 per cent of the mining sites in Eastern Congo, which manifests in the form of illegal taxation and extortion. As such, further acquisitions by M23 in Eastern Congo may put the DRC’s mineral sector under further strain.

The United Nations troop withdrawal

The escalation of the M23 conflict coincides with the United Nations’ plan to pull the entirety of their 13,500 peacekeeping troops out of the region by the end of the year upon the request of the recently re-elected government. With UN troops withdrawn, a military power vacuum is likely to form, thereby worsening insecurity and further damaging the DRC’s mining sector. However, regional armed groups are not the only actors that can clog this gap.

Regional international involvement

A further problem for the DRC’s mining sector is that the country’s political centre, Kinshasa, is located more than 1,600 km away from North Kivu, while Uganda and Rwanda share a border with the province.

Figure: Air travel distance between Goma and Kinshasa, Kigali and Kampala (image has been altered from the original)

The distance limits the government’s on-the-ground understanding of regional developments, including the extent of the involvement of armed groups in the ASM sector, thereby restricting the Congolese military’s effectiveness in countering regional rebellions.

In 2022, UN experts found ‘solid evidence’ that indicates that Rwanda is backing M23 fighters by aiding them with funding, training, and equipment provisions. Despite denials from both Kigali and M23 in explicit collaboration, Rwanda admitted to having military installments in eastern Congo. Rwanda claims that the installments act as a means to defend themselves from the Democratic Forces for the Liberation of Rwanda (FDLR)–an armed rebel group that Kigali asserts includes members who were complicit in the Rwandan genocide. The FDLR serves as a major threat to Kigali’s security, as its main stated aim is to overthrow the Rwandan government.

As such, M23, on the other hand, provides Rwanda with the opportunity to assert influence in the region and limit FDLR’s regional influence. Tensions between Rwanda and the DRC have, therefore, heightened, especially with the added fact that the Congolese army has provided FDLR with direct support to help the armed group fight against M23 rebels. As such, the DRC has been accused of utilising the FDLR as a proxy to counter Rwandan financial interests in the Congolese mining sector.

Another major point of contention between the states involves the smuggling of minerals. The DRC’s finance minister, Nicolas Kazadi, claimed Rwanda exported approximately $1bn in gold, as well as tin, tungsten, and tantalum (3T). The US Treasury has previously estimated that over 90 per cent of DRC’s gold is smuggled to neighbouring countries such as Uganda and Rwanda to undergo refinery processes before being exported, mainly to the UAE. Rwanda has repeatedly denied the allegations.

Furthermore, the tumultuous environment caused by the conflict might foster even weaker checks-and-balance systems, which will exacerbate corruption and mineral trafficking, which is already a serious issue regionally.

In previous surges of Congolese armed rebel violence, global demand for Congolese minerals plummeted, as companies sought to avoid problematic ‘conflict minerals’. In 2011, sales of tin ore from North Kivu decreased by 90 per cent in one month. Similar trends can be anticipated if the M23 rebellion gains strength, which may create a global market vacuum for other state’s exports to fill.

China

In recent years, China gained an economic stronghold of the DRC’s mining sector, as a vast majority of previously US-owned mines were sold off to China during the Obama and Trump administrations. It is estimated that Chinese companies control between 40 to 50 per cent of the DRC’s cobalt production alone. In an interest to protect its economic stakes, China sold nine CH-4 attack drones to the DRC back in February 2023, which the Congolese army utilised to curb the M23 expansion. Furthermore, Uganda has purchased Chinese arms, which it uses to carry out military operations inside of the DRC to counter the attacks of the Allied Democratic Forces (ADF), a Ugandan rebel group, which is based in the DRC. In return for military support, the DRC has granted China compensation via further access to its mining sector, which is helping bolster China’s mass production of electronics and technology within the green sector.

The US

Meanwhile, the US has put forth restrictions on imports of ‘conflict minerals’, which are minerals mined in conflict-ridden regions in DRC for the profit of armed groups. Although the US attempts to maintain certain levels of mineral trade with the DRC, the US’s influence in the country will likely continue to phase out and be overtaken by Beijing. The growing influence of M23 paves the path for further future collaboration between China and the DRC, both militarily and economically within the mining sector.

The UAE

The UAE, which is a major destination for smuggled minerals through Rwanda and Uganda, has since sought to end the illicit movement of Congolese precious metals via a joint venture that aims to export ‘fair gold’ directly from Congo to the UAE. In December of 2022, the UAE and DRC signed a 25-year contract over export rights for artisanally mined ores. The policy benefits both the DRC and the UAE as the UAE positions itself as a reliable partner in Kinshasa’s eyes, which paves the path for further business collaboration. In 2023, the UAE sealed a $1.9bn deal with a state-owned Congolese mining company in Congo that seeks to develop at least four mines in eastern DRC. The move can be interpreted as part of the UAE’s greater goal to increase its influence within the African mining sector.

Global Shifts

China and the UAE’s increasing involvement in the DRC can be seen as part of a greater diversification trend within the mining sector. Both states are particularly interested in securing a stronghold on the African mining sector, which can provide a steady and relatively cheap supply of precious metals needed to bolster the UAE’s and China’s renewables and vehicle production sectors. The scramble for control over minerals in Congo is part of the larger trend squeezing Western investment out of the African mining sector.

Furthermore, the UAE’s increasing influence in the DRC is representative of a larger trend of the Middle East gaining more traction as a rival to Chinese investment in Africa. Certain African leaders have even expressed interest in the Gulf states becoming the “New China” regionally, as Africa seeks alternatives to Western aid and Chinese loans.

Although Middle Eastern investment is far from overtaking China’s dominance of the global mining sector, an interest from Africa in diversifying their mining investor pools can go a long way in changing the investor share continentally. Furthermore, if the Middle East is to bolster its stance as a mining investor, Africa serves as a strategic starting point as China’s influence in the African mining sector is at times overstated. In 2018, China is estimated to have controlled less than 7 per cent of the value of total African mine production. Regardless, China’s strong grip on the global mining sector might be increasingly challenged through investor diversification in the African mining sector. The DRC is an informant of such a potential trend.

The further spread of the M23 rebellion, though likely to damage the Congolese mining business, might also foster stronger relations with countries such as the UAE which seek to minimise ‘conflict mineral’ imports. As such, the spread of the M23 rebellion–which acts as a breeding ground for smuggling, might catalyse new and stronger trade relations with the Middle East. This could be indicative of a trend of “de-Chinafication” in the region, or at least greater inter-regional competition for investment into the African mining sector.

An EU Hope: Sourcing Critical Raw Materials from South America

Expansion of the EU’s raw material supply agreements with South America.

In light of the Russian-Ukraine conflict, European countries have been facing a raw material supply crisis. Disrupted supply chains have significantly contributed to the rise in the price of critical minerals, causing lithium and cobalt to double and other essential energy commodities such as gas to increase 14-fold in price over the span of 3 years. The EU has sought new trade partners to mitigate price rises and reduce their dependence on countries such as China and the US, aiming to secure a sustainable supply chain of critical raw materials. The prime candidates for this venture have been South American countries, a region with cultural and historic ties to the EU. Countries in this region are characterised by an abundance of natural resources and arable land, and their economic reliance on commodity exports provides an incentive to create trade partnerships. As a consequence, recent years have seen efforts to develop bilateral relations and trade in goods and services with the EU.

Recent Developments

The most recent development in the EU’s bid to secure critical raw materials has been intensified cooperation with Argentina. President Alberto Fernández and European Commission head Ursula von der Leyen signed a memorandum on June 13 to expand cooperation between Argentina and the European Union in sustainable value chains of critical raw materials. The goal of the agreement is to guarantee a steady and sustainable supply of commodities needed to ensure the clean energy transition, namely minerals, for European countries. The agreement is collaborative in nature, as the EU plans to invest in research and innovation in Argentina, with a special focus on minimising the climate footprint of extractive activities such as mining. While the EU secures a steady inflow of commodities, Argentina profits from quality job creation, increased sustainability, and economic growth from commodity exports, boosting its staggering economy.

Mercosur

Argentina, along with eleven other South American countries, make up the regional trade bloc Mercado Común del Sur (Mercosur). Trade between the EU and Mercosur is plentiful, with the EU being Mercosur's largest trade and investment partner. As of 2021, the EU exported €45 billion to and imported €43 billion from Mercosur. The EU imports mostly mineral and vegetable commodities and exports machinery, appliances, chemicals, and pharmaceutical products. In 2019, the EU sought to intensify this partnership by establishing a political agreement with decreased trade frictions, namely tariffs for small and medium sized enterprises, creating stable rules for trade and investment, and establishing environmental regulations and policies in all Mercosur countries. This agreement, however, has remained in a provisional stage ever since, as efforts to reach a consensus have been stunted by certain conflicting interests.

Graphical Representation of Main EU Imports from Mercosur from 2011 to 2021

Source: Eurostat

Cooperation Friction

There are various conflicting interests that prevent this deal from going through. For one, Brazil, Mercosur's largest economy, has plans for intensified cooperation with China, one of its main trade partners. Argentina has also increased cooperation with China in recent years, adding to tensions in EU relations. Brazilian President Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva, the current Mercosur president, has also expressed his disapproval of the proposed agreement. Brazil has had intense deforestation in recent years, and although the current Brazilian presidency has decreased these efforts, policies proposed by the EU in the agreement would interfere with domestic policy and development in their agricultural production. Various clauses prohibit the export of products from deforested areas, demand strict labour laws, and provide public procurement rights to EU and Mercosur companies, limiting the Brazilian government's agricultural and industrial policies and weakening its ability to control domestic production autonomously. Lula has taken a stand against this interference and denounces the agreement for reducing South American countries to indefinite commodity suppliers to Europe.

Various producers in European countries have also voiced their discontent with the deal. With lower commodity prices arising from reduced tariffs and trade restrictions, farmers and raw material producers in these countries would face extremely low prices and struggle to remain competitive. In France, local farmers fear losing profits as a result of an inflow of cheap imported beef. Despite expressing their interest in creating exceptions for agricultural products, farmers know these provisions would be unpopular with Mercosur producers and are thus unlikely to be included in the agreement. Although these farmers’ influence is not as prominent as that of other actors, protests and disruptions have been a cause for concern in the past. There is the possibility of further aggravating the current clashes over pension reforms, which place the French government in a delicate situation. EU member states could face scrutiny if the pact goes through for neglecting local producers and destroying domestic markets, although this might be a risk governments are willing to take in order to secure energy commodities.

Environmentalist organisations also oppose the agreement. Greenpeace has encouraged protests in Brussels against the "poisonous treaty" that aims to increase trade in environmentally detrimental commodities. A particular disapproval of the lower export prices of pesticides was cited in their protests, along with the more pressing matter of deforestation for cultivation in Brazil. These perspectives are shared by various member states in the EU, and their combined efforts have provided advances in the vein of sustainability. In various dealings, member states such as Austria, France, Ireland, Luxembourg, and Belgium have advocated for enforceable provisions regarding environmental issues, and their veto power places pressure on other member states to comply.

Future Prospects

The EU’s most recent supply acquisition, Argentina, will soon face political change that could affect their cooperation. Unlike Lula, who has three years left in his term, Argentine President Alberto Fernandez will be out of office as of December of this year, and the new government could increase friction in the agreement. Various candidate parties in Argentina have ideologies that differ greatly from Lula’s left-leaning policies, and their contrasting economic plans could decrease both bilateral relations and cooperation in Mercosur. Furthermore, the Mercosur deal, along with the bilateral agreement between Argentina and the EU, stipulates environmental policies and regulations for the country’s extractive activities that could slow their development. With Argentina planning on hastily developing oil and gas extraction in Vaca Muerta, these stipulations could very well be violated and harm both deals with the EU. This applies to many Mercosur countries that rely on primary activities but also want to develop other sectors that may have negative environmental impacts, namely industrial production. With economic growth being the main focus of Mercosur states, it is unlikely that they will accept a deal that would hinder development of any kind.

As seen, the political inclinations and plans for economic development of each Mercosur country have vast implications for the bloc’s ability to close a deal with the EU. With Lula’s rise to power, a change in government policy, in this case a decrease in deforestation, favoured the EU’s intention of creating a clean energy supply chain and reinvigorated expectations for cooperation. Nonetheless, the environmental implications of most Mercosur countries’ production models and their cooperation with countries like Russia and China create distrust between both blocs and stunt advances in the agreement. It seems that the EU’s inability to renegotiate environmental policy due to pressure from environmentalist organisations and specific member states will require a complacent Mercosur to finalise dealings. Although the possibility of splitting the agreement into two different parts exists, thus circumventing sustainability policy, it is unlikely the bloc will follow this path as it would aggravate various member states. Mercosur’s strong conviction for sovereignty will prevent them from accepting the stringent regulations currently proposed by the EU, and the EU’s apparent unwillingness to cede certain stipulations will further aggravate tensions between blocs and cause dealings to remain stagnant. With many South American countries undertaking long-haul projects on agricultural production and extractive activities with potential environmental implications, such as Argentina’s 10-year oil pipeline investment, the agreement will likely continue to face conflicts for the next two to five years. Although Lula promised at the July summit with the EU to deliver a definite proposal that is “easy to accept” soon, his declarations against the last draft’s stringent nature put into question whether this version will comply with the requirements stipulated by the EU. As demand from alternative countries like China grows, Mercosur will be less inclined to accept terms that harm its development, causing dealings to drag on until the EU complies.

Africa in the “white gold” rush

The global supply of lithium ore has become an increasingly tangible bottleneck as many countries move towards a green transition. The International Energy Agency (IEA) predicted that the world could face a shortage of this key resource as early as 2025, as demand continues to grow. The increasing popularity of electric vehicles (EVs), which saw sales double in 2021, as well as other products which require lithium batteries, have been primary factors in this supply crunch.

Demand for lithium (lithium carbonate in this case) has driven high prices, which also nearly doubled in 2022, over $70,000 a tonne, and put pressure on the mining industry to increase production. This has led to heightened competition over this strategic resource and a rush to explore new reserves. An emerging arena in this competition has been Sub-Saharan Africa which has the potential to become a major player in lithium production, behind already established producers in South America and Australia. This region does, however, pose a unique set of challenges for lithium production in terms of infrastructure as well as a diverse and risk prone political constellation.

Within the region there are several countries which have already been tapped as potential producers or have already developed some degree of extraction capacity. Among these are Mali, Ghana, the DRC, Zimbabwe, Namibia and South Africa, at this stage most of these countries are at some stage of exploration, development or pre-production, currently only Zimbabwean mines are fully operational.

The political instability in some of these countries is a primary concern in the future of lithium production. Mali stands out in this regard with the withdrawal of the French intervention force in 2022, after nearly 10 years, and the ensuing power vacuum. In other countries such as the DRC political risk has been largely tied to corruption in governance which limits competition potential as well as human rights and environmental concerns which emerged around cobalt mining.

Zimbabwe offers a perspective into the most developed lithium operation in the region. In early 2022, Zimbabwe’s fully operational Bitka mine was acquired by the Chinese Sinomine Resource Group. Also in 2022, Premier African Minerals, the owners of the pre-production stage Zulu mine, concluded a $35 million deal with Suzhou TA&A Ultra Clean Technology Co. which was set to see first shipments in early 2023. This was followed by a similar $422 million acquisition of Zimbabwe's second pre-production mine Arcadia by China’s Zhejiang Huayou Cobalt.

Zimbabwe’s government responded to this mining boom by banning raw lithium exports stating that “No lithium bearing ores, or unbeneficiated lithium whatsoever, shall be exported from Zimbabwe to another country.” This move is intended to keep raw ore processing within the country, and despite initial appearances will not apply to the Chinese operation, whose facilities already produce lithium concentrates. Yet, this policy does demonstrate the active role that the government is able to play in the market, and their willingness to harness this economic windfall.

Even the most developed lithium mining operations in the region must pay close attention to the political situation unfolding around them. As competition over this strategic resource becomes more acute, the role of soft power will likely play a key role in negotiating favourable terms and preferential treatment in the exploitation of lithium reserves.

Potash supply in a de-globalising world

International sanction regimes are disrupting supply chains across the world. In this research paper, analysts from London Politica’s Global Commodities Watch (GCW) provide an overview of the major stakeholders, critical infrastructure, trade routes, supply and demand side risks, and forecasted trends for potash.

Potash is a fertiliser, essential for increasing agricultural yields and feeding the growing population of the world.