2024 Elections Report: Risks & Opportunities for Commodities Sector

In the ever-evolving landscape of global commodities, the year 2024 stands as a pivotal juncture marked by transformative elections across diverse regions. As nations prepare to cast their ballots, the outcomes hold the power to shape policies and strategies that will significantly influence energy, trade relations, and resource management worldwide.

This report encapsulates the intricate intersections between political shifts and their repercussions on the commodities sector. London Politica’s Global Commodities Watch has made a selection of the most significant countries, and analysed the potential impact of elections based on election programmes, past policies, and scenario planning.

Russo-Ukrainian War and Energy Security in the Visegrad 4

Energy security has been a concern of modern policy-making for decades, yet its increasing importance has been thrust into greater spotlight by more recent events, namely the invasion of Ukraine by Russia in February 2022. Grappling with the fallout of the conflict, the European Union (EU) suddenly had to face new and re-emerging challenges, including disrupted supply chains and the weaponization of energy by Russia, both in Ukraine and against EU Member States. With strong political will and a collective desire to end the first major conflict on the continent since the Second World War, Member States individually, as well as the supranational body as a whole raced to secure their own energy supply through policy and diversification. Nevertheless, challenges remain, especially for states with some of the closest ties to Russia, Ukraine, and their energy supplies.

Read here for London Politica’s latest report on the situation with European energy, a collaborative analysis from team members from Global Commodities and Europe Watch and Conflict and Security Watch.

India's Growing Reliance on Russian Oil Imports

Since Russia's full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022, India’s reliance on Russian crude oil has increased tenfold. The proportion has risen from as little as 2% of total crude imports in 2021/2022, to 20% in June 2023. Recent estimates suggest that this percentage may reach as high as 30% by the end of the year.

In the wake of the invasion, there has been a largely concerted effort to sanction Russia’s economy and prevent it from further funding their war of aggression. A key component of the sanctions have been directed at Russia’s oil industry, Russia being the world's third largest producer and second largest crude oil exporter.

In December 2022, the EU’s sixth sanctions package came into effect, banning seaborne crude oil and petroleum products from Russia (90% of total oil imports from Russia). This move complimented similar bans enforced in the USA and the UK. Yet an additional component of the combined sanctions effort has been a price cap on Russian crude oil, which set the maximum price at $60 per barrel of crude. Despite the fact that the G7 countries (USA, UK, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, Canada and the EU) have already agreed to ban or phase out Russian crude imports, the cap has given leverage to uninvolved countries, including India, when negotiating prices with Russia.

The rapid increase in Indian imports from Russia suggests that India has been able to harness Russia’s weakened bargaining position. At the same time this new arrangement has put downward pressure on the oil prices charged India’s former suppliers in OPEC, primarily, Iraq and Saudi Arabia

Source: Reuters

The price differential between Russian and OPEC sourced crude, provides a clear basis in explaining India’s shift. Taking the April 2023 price as a point of comparison, India was able to pay as little as $68 per barrel for Russian imported oil, while oil from Iraq (traditionally India’s largest supplier) was priced at $77 per barrel and oil from Saudi Arabia cost as much as $86 per barrel. During the month of April, the overall OPEC basket price ranged from $79 to $86 per barrel. The price gap between OPEC suppliers and Russia makes a clear case for India’s growing imports from Russia, while the significantly lower price of Russian crude demonstrates the impact of the $60 price cap.

Source: Euronews

The challenges posed by India’s growing taste for Russian oil are twofold. In the first instance, while the price of Russian oil is considerably lower than OPEC in this case, the $68 per barrel price tag is still well over the imposed price cap, revealing the limitations of the price cap regime. In the second instance, India has become a rapidly growing market for Russian oil and as such a prop for the Russian war economy. While EU oil imports declined, figure 2 shows the relative increase of Indian oil imports, partially offsetting the impact of oil sanctions. India’s growing reliance on imported Russian oil has already become a point of contention with Western leaders. With the forecasted increase of India’s Russian oil imports, it is likely to remain so.

Image credit: President of Russia via Wikimedia Commons

Powering the future: Cobalt in the EV battery value chain

Powering the future: Cobalt in the EV battery value chain

This research paper sheds light on the key risks associated with the supply of cobalt, a critical mineral for the production of electric vehicle (EV) batteries. With demand for EVs projected to grow steadily in the coming decade, it is crucial that companies mitigate these risks. The concentration of finite cobalt reserves in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) and the concentration of refining capacities in China create a delicate balance of supply that is highly risk prone.

The Risks to Indonesia’s Nickel Boom

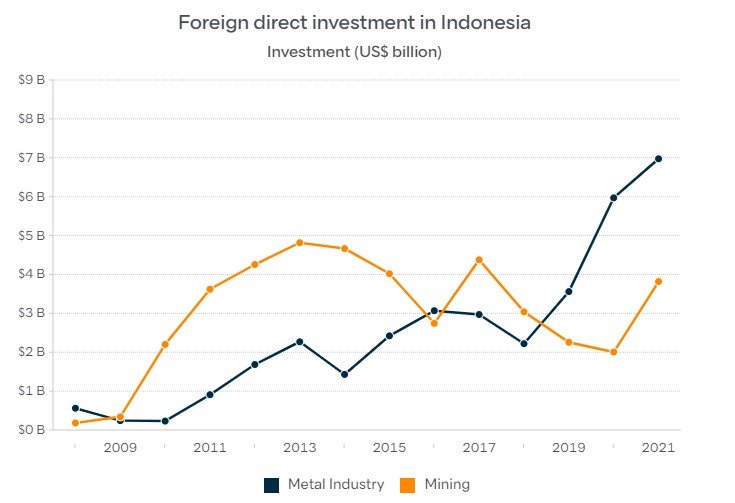

In January 2020, the Indonesian government banned the export of raw nickel ore in a bid to spur investment in domestic added-value mineral processing. While the protectionist move was met with criticism from the World Trade Organization (WTO), which ruled against the “unfair” policy, Indonesia is experiencing a boom in foreign direct investment focusing on their mining and metal industries.

Foreign Direct Investment in Indonesia in selected industries. Image Credit: Lowy Institute

Yet with the growing importance of the nickel industry and Indonesia’s key position by having the largest known nickel reserves, the country is now open to a range of potential risks. From environmental and sustainability concerns to great power politics between the United States and China, there are many challenges ahead.

Explaining nickel supply:

While nickel demand is still dominated by the stainless steel industry, the rapidly expanding battery industry, most importantly for electric vehicles (EV), has become one of the primary drivers of increased interest in Indonesian nickel. Since the beginning of 2020 the price per tonne of nickel has jumped from roughly 14,000 USD to over 23,000 USD today, further indicating the rising demand for the metal.

One exceptional case that must be added is that prior to the war in Ukraine, Russia produced around 20% of global Class 1 battery-grade nickel supply. The onset of the war in early February 2022 led to extreme fluctuation in prices and while this has largely stabilised, between 20,000 and 30,000 USD per tonne, the war will likely continue to apply pressure on nickel supply. While Russian nickel exports have so far avoided sanctions from the US and EU, supply precarity and potential interruption have made finding alternative sources a priority.

There are several key players in nickel production which offer alternatives to Russian sources. The first group, which rely on the more easily processed nickel sulphide ore, are Canada and Australia, with Russia also counting among these. The second category of producers, which rely on nickel laterites, are the Philippines, New Caledonia and most importantly Indonesia.

Indonesian production and its challenges:

Since the ban on ore export in 2020, Indonesia has concluded deals worth more than $15bn for the production of nickel based battery components. These deals include major players in the broader EV market, such as Ford, LG, Hyundai, Foxconn, Zhejiang Huayou Cobalt and others. These deals have also pitted the US and western aligned countries against China in the heated competition over EV supply chains. The rapid development of Indonesia’s nickel mining industry has seen production increase by 13 per cent in 2022 compared to 2021.

The growth of the mining and metal processing industry also has significant environmental and social impacts on Indonesia.

Allegations of workers rights violations in a Chinese facility draws attention to a lag in government oversight. In January 2023 a violent clash, between workers, security guards and protesters, broke out at the Gunbuster Nickel Industry smelter, a facility of the Chinese Jiangsu Delong Nickel Industry, leaving two dead. This is a further indication of the social tensions caused by such quick development and the lack of proper regulation and oversight by the government. In the long term this represents a tangible risk to Chinese interests, and potentially for others, as compromises will need to be made with workers and work stoppages remain a possibility.

At the same time the Indonesia government has been put under considerable scrutiny for the environmental ramifications of rushed and poorly regulated mining operaterations. At mining sites on the Sulawesi and Maluku islands, run-off pollution turned coastal water a “deep red” affecting the local fishing economy as well as raising health concerns in the local communities. Additionally, the problem of deforestation for mining has spurred the Indonesian government to pledge to “reforest” depleted mines, though livelihoods based on forest products, notably clove trees, have already been affected.

The negative impact of the nickel industry has already influenced potential investors. Elon Musk's proposal to build an EV manufacturing “gigafactory” in Indonesia was met by environmental petitions pressuring him not to invest. The environmental risk is high, and comes at a steep price for the Indonesian people. The government will need to weigh the cost of rapid development in the short term with the long term impact of environmental degradation.

Powering the future: Lithium in the EV battery value chain

Powering the future: Lithium in

the EV battery value chain

This research paper is the first in a series covering the numerous risks associated with electric vehicle (EV) battery production. Each paper delves into a specific mineral that is vital to this process, starting off with lithium. This series is brought by a team of analysts from the Global Commodities Watch.

Africa in the “white gold” rush

The global supply of lithium ore has become an increasingly tangible bottleneck as many countries move towards a green transition. The International Energy Agency (IEA) predicted that the world could face a shortage of this key resource as early as 2025, as demand continues to grow. The increasing popularity of electric vehicles (EVs), which saw sales double in 2021, as well as other products which require lithium batteries, have been primary factors in this supply crunch.

Demand for lithium (lithium carbonate in this case) has driven high prices, which also nearly doubled in 2022, over $70,000 a tonne, and put pressure on the mining industry to increase production. This has led to heightened competition over this strategic resource and a rush to explore new reserves. An emerging arena in this competition has been Sub-Saharan Africa which has the potential to become a major player in lithium production, behind already established producers in South America and Australia. This region does, however, pose a unique set of challenges for lithium production in terms of infrastructure as well as a diverse and risk prone political constellation.

Within the region there are several countries which have already been tapped as potential producers or have already developed some degree of extraction capacity. Among these are Mali, Ghana, the DRC, Zimbabwe, Namibia and South Africa, at this stage most of these countries are at some stage of exploration, development or pre-production, currently only Zimbabwean mines are fully operational.

The political instability in some of these countries is a primary concern in the future of lithium production. Mali stands out in this regard with the withdrawal of the French intervention force in 2022, after nearly 10 years, and the ensuing power vacuum. In other countries such as the DRC political risk has been largely tied to corruption in governance which limits competition potential as well as human rights and environmental concerns which emerged around cobalt mining.

Zimbabwe offers a perspective into the most developed lithium operation in the region. In early 2022, Zimbabwe’s fully operational Bitka mine was acquired by the Chinese Sinomine Resource Group. Also in 2022, Premier African Minerals, the owners of the pre-production stage Zulu mine, concluded a $35 million deal with Suzhou TA&A Ultra Clean Technology Co. which was set to see first shipments in early 2023. This was followed by a similar $422 million acquisition of Zimbabwe's second pre-production mine Arcadia by China’s Zhejiang Huayou Cobalt.

Zimbabwe’s government responded to this mining boom by banning raw lithium exports stating that “No lithium bearing ores, or unbeneficiated lithium whatsoever, shall be exported from Zimbabwe to another country.” This move is intended to keep raw ore processing within the country, and despite initial appearances will not apply to the Chinese operation, whose facilities already produce lithium concentrates. Yet, this policy does demonstrate the active role that the government is able to play in the market, and their willingness to harness this economic windfall.

Even the most developed lithium mining operations in the region must pay close attention to the political situation unfolding around them. As competition over this strategic resource becomes more acute, the role of soft power will likely play a key role in negotiating favourable terms and preferential treatment in the exploitation of lithium reserves.

Risks of the German gas plans

This comprehensive mini-report from the Global Commodities Watch identifies the risks involved with German preparations and plans to curtail Russian gas supplies.

State of supply: uranium in Europe

Despite being a strategic commodity, uranium has maintained a relatively low profile in the news even as the war in Ukraine continues and Europe’s energy crisis unfolds. This is surprising considering nuclear power, which depends on uranium, contributes roughly 25% of the EU’s total electricity generation. Russia itself has long been a key supplier of uranium and nuclear fuel to the EU, but the future of this relationship is now far from certain. For the moment, Rosatom, Russia’s state-owned and primary vendor of nuclear products, has managed to skirt EU sanctions and continue operating, but how long can this last and what does it mean for nuclear energy in Europe?

In terms of unenriched Uranium ore, Russia is the third largest supplier to the EU. In 2021 it accounted for 19.69% of supply, just behind Kazakhstan at 22.99% and Nigeria at 24.26%. This equates to 2,358 tU (tons of raw Uranium) and roughly €210 million paid to Russian vendors in 2021. However, Russia’s position in third place can be somewhat misleading, according to the World Nuclear Association and other sources, Rosatom owns significant stakes in uranium mining and processing in Kazakhstan. Nigeria has been ramping up its supply of uranium ore in recent years with an increase of 13.7% between 2020 and 2021. Considering the ongoing expansion of mining operations in the country, Nigeria may emerge as a leading supplier for Europe, if output can be maintained.

Unenriched uranium ore is only half of the equation when it comes to generating nuclear energy. The other key ingredient is refined or enriched uranium, suitable for nuclear fuel production. Europe is dependent on foreign enrichment services. While Europe itself manages some 62% of its enrichment needs, as of 2021, 31% is still sourced from Russian providers. The two primary Russian providers, according to Euratom, are Tenex and TVEL, which are both subsidiaries of Rosatom. Over the past few years, EU domestic enrichment rates have decreased, between 2019 and 2020 alone Euratom marked a 9% decrease in its share. In order to ensure security of supply in this sector, Europe must reverse this trend and look for third country partners. The current non-Russian and non-EU supply of enrichment services amounts to an astonishingly low 7%, a critical failure in market diversification.

The other side to the issue with enriched Uranium supply is the specific fuel configuration for reactors. Of the 103 active nuclear reactors in the EU, 18 are of the Russian designed VVER-440 or VVER-1000 models and depend greatly on fuel supply from TVEL. While many of these reactors are holdovers from original Soviet construction and are set to be phased out in the long term, they still represent an imminent threat. Mitigating this however, the US’s Westinghouse, a leading provider of nuclear infrastructure, is currently expanding its capacity to produce fuel at least for the VVER-1000 models; this has already been successful in Ukraine.

The situation for Europe’s uranium supply is precarious and the fact Russia’s supply has not yet collapsed, is of little consolation. Nonetheless, there are options on the table and unlike other commodities, uranium has the potential for a diverse supply chain with multiple partners. Two key questions are how long will it take to reorganise these highly complex, infrastructure heavy supply chains and how long will the EU continue its economic relationship with Russia?