Powering the future: Cobalt in the EV battery value chain

Powering the future: Cobalt in the EV battery value chain

This research paper sheds light on the key risks associated with the supply of cobalt, a critical mineral for the production of electric vehicle (EV) batteries. With demand for EVs projected to grow steadily in the coming decade, it is crucial that companies mitigate these risks. The concentration of finite cobalt reserves in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) and the concentration of refining capacities in China create a delicate balance of supply that is highly risk prone.

Powering the future: Lithium in the EV battery value chain

Powering the future: Lithium in

the EV battery value chain

This research paper is the first in a series covering the numerous risks associated with electric vehicle (EV) battery production. Each paper delves into a specific mineral that is vital to this process, starting off with lithium. This series is brought by a team of analysts from the Global Commodities Watch.

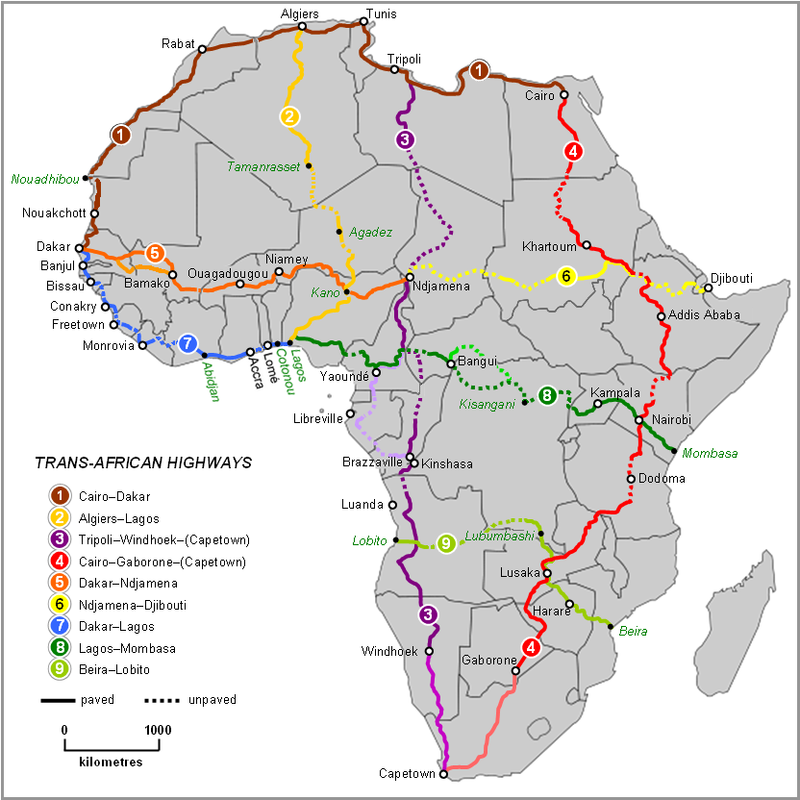

All roads lead to Africa: Opportunities and risks of the Trans African Highway network

In the build up to Nigeria’s next presidential elections due on 25 February 2023, the ruling All Progressives Congress (APC) party has suggested a suspension of spending limits in the budgetary process in its manifesto. According to presidential candidate Bola Tinubu, this would allow the government to “hire millions of unemployed Nigerians to modernise national infrastructure”, arguing that “a truly national highway system must be built to make road transportation faster, cheaper, and safer”. In the past, Minister for Public Works and Housing Babatunde Fashola has highlighted that these efforts transcend Nigeria’s borders, notably with the completion of the Trans–West African Coastal Highway (TAH 7): “We’re trying to deliver a better life for five countries and over 40 million people who use that corridor, almost on a daily basis. [...] The future is bright, this is an important investment for the people of Africa to achieve the objective of the Africa Union (AU) to create a trans-African highway.’’

Source: The Trans African Highway network, Wikimedia Commons, 2007.

The opportunities

This reinvigorated optimism for transnational transportation across the continent is embodied in the Trans African Highway (TAH) network, developed by the United Nations Economic Commission for Africa (UNECA), the African Development Bank (ADB), and the AU in conjunction with regional organisations. Financing is also supported by foreign development funds. The pursuit of such projects is vital to the development of African countries. In fact, the IMF estimates that around 40 per cent of the continent’s population lives in a landlocked country. Yet considering the high economic dependence of most African states on commodity exports and the low levels of intracontinental trade ー extra-African merchandise exports represented 86.6 per cent of total exports in goods from Africa in 2019 ー access to global shipping routes is vital. The completion of the TAH network coincides with the gradual setting up of the African Continental Free Trade Agreement (AfCFTA) which seeks to create a free trade zone encompassing all African Union states (bar Erythrea) and lift 30 million people out of extreme poverty by increasing intercontinental trade. UNECA highlights that the operationalisation of the AfCFTA will stimulate demand for land transportation and “double road freight from 201 to 403 million tonnes”.

The risks

Besides these potential opportunities, the gargantuan TAH network presents several economic, political, environmental, social and security risks. Economically speaking, the main risk source is the difficulty for developing countries to cover the high costs of maintenance. According to the World Bank, lack of maintenance can have aggravating socio-economic consequences: “poorly maintained roads constrain mobility, significantly raise vehicle operating costs, increase accident rates and their associated human and property costs, and aggravate isolation, poverty, poor health, and illiteracy in rural communities”. Furthermore, the South African National Road Agency estimates that “repair costs rise to six times maintenance costs after three years of neglect and to 18 times after five years of neglect”.

Politically speaking, an important risk source to the success of TAHs is the potential lack of cooperation of neighbouring states. Diplomatic leverage may be found in increasing bureaucratic processes at border crossings to cause congestion and delays ー although this risk may decrease in the long term as the AfCFTA is gradually implemented and imposes lighter border controls.

Environmentally and socially speaking, risk sources mostly emanate from rural areas. TAH projects may have to provide environmental mitigation and compensation for any ecological damage caused during construction phases, as well as go through long and complex acquisition processes due to tribal land ownership rules.

Finally, from a security perspective, the risk of land route disruptions and damage to infrastructure is extremely high in regions where conflict may arise, as is the case for the Ethiopian portion of TAH 4 which runs past the country’s war-torn northern regions.

Overall, the TAH network will undoubtedly help with African development through intracontinental trade. Yet, making this development sustainable for the decades to come will be a challenging feat Africans are already fully aware of: in the AfCFTA Secretariat's own words, “economic integration is not an event. It’s a process”.

Providing for the Peninsula

This collaborative research paper by London Politica’s Global Commodities Watch and Ukraine Watch sheds light on the critical infrastructure for the supply of Russian water, fuel and military equipment through and for Crimea and investigates how these may be affected by pressure from Ukrainian forces in the months to come.

Wheat supply in a de-globalising world

International sanction regimes are disrupting supply chains across the world. In this research paper, analysts from London Politica’s Global Commodities Watch (GCW) provide an overview of the major stakeholders, critical infrastructure, trade routes, supply and demand side risks, and forecasted trends for wheat.