Central and Eastern European countries are well-prepared for the next 2023/2024 heating season, but risks still loom large

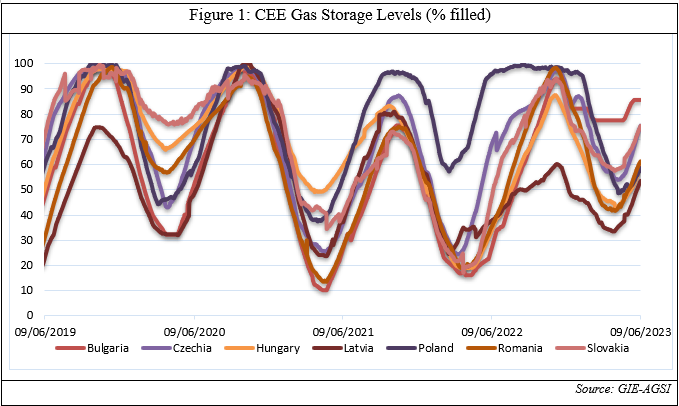

Central and Eastern European (CEE) countries are well-prepared for the next 2023/2024 heating season, despite the presence of moderate risks. This is due to two factors. Their strategies to diversify from Russian gas have been overall successful, and current gas storage levels are high. As of June 2023, they are considerably higher than in the same period last year. While at the beginning of June 2023 they amounted to an average of 49%, nowadays storage facilities are filled between 53.5% (Latvia) and 85.6% (Bulgaria). What emerges is a positive situation with regard to the CEE’s energy security in winter 2023/2024. Indeed, according to the EU Gas Storage Regulation (EU/2022/1032), to ensure reasonable gas prices in the next heating season, EU countries have to reach a storage level of 90% before October 2023. Considering that all CEE states have achieved the intermediate targets for May set out in the regulation and that they still have the entire summer to build up their gas storage facilities, they will likely reach the EU-mandated level of 90% before next winter.

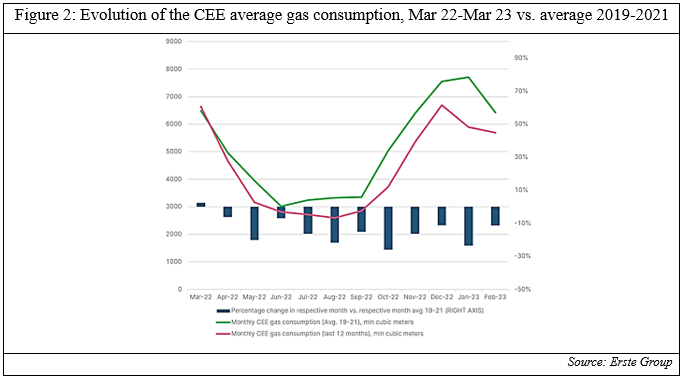

Moreover, the CEE states have also reduced their vulnerability to Russian gas by reducing their total demand for natural gas and diversifying their suppliers. When looking at the gas consumption in the region over the last 12 months as opposed to the average between 2019 and 2021, it can be noted that it decreased by 14% -more than the Eu average reduction of 11%- with a more visible decline taking place since mid-2022 [Figure below]. At the same time, they also diversified the remaining gas imports away from Russia, importing natural gas from Scandinavian countries (especially Norway) and LNG from overseas, including the US. In this regard, CEE countries were supported by the construction, ahead of the 2022/2023 heating season of several gas interconnectors, i.e., physical infrastructure systems that enabled natural gas transportation from other European countries. All these factors allowed the CEE to reduce its dependence on Russia.

In 2022, the IMF estimated that a potential Russian gas supply shut-off would have led to a GDP output loss of an average of 2.8%, compared to an EU average of 2.3%. In the short term, Hungary, the Slovak Republic and Czechia -which were the most vulnerable CEE countries- were expected to experience gas consumption shortages of up to 40% and a potential GDP decline of up to 6%. However, even if later in 2022 Russia did halt its gas supplies to the CEE, the expected gas shortages did not materialise. And while the CEE annual growth rate will slow down to an average of +0.6% in 2023 according to the European Commission, this is still double the expected EU average 2023 growth, and the output losses were considerably less than what was projected a year earlier by the IMF. In other words, countries in the region have so far proved to be economically resilient.

Nevertheless, the CEE still faces challenges regarding its energy security. Mainly, this relates to the steep surge in energy prices in the region following Russia’s weaponisation of gas supplies to the EU. After Gazprom unilaterally changed the terms of its gas supply contracts demanding payments in rubles, it halted all supplies to Poland and Bulgaria, which refused to pay according to the new rules. Even if Slovakia, Czechia and Hungary agreed to pay in rubles, Russian gas flows were anyway gradually stopped. First, Russian supplies through the Yamal pipeline ceased in May 2022, then, gas in transit through Ukraine also significantly decreased. Lastly, in August 2022 Moscow completely stopped the Nord Stream 1 pipeline. To date, the main way Russian gas flows to Europe is via the TurkStream route (which however supplies only Hungary and Serbia). The other is the Ukraine route, but this is likely to reduce in the coming months. As a result, energy prices in the region rose substantially, affecting especially energy-intensive industries. In 2022, producer energy prices increased by 93%. Coupled with the increase in inflation and the decision by CEE central banks to raise their policy interest rates, the increase in energy prices led to a surge in the production costs of CEE industries. As the CEO of Volkswagen Thomas Schafer claimed “Europe is not cost-competitive in many areas, in particular, when it comes to the costs of electricity and gas”. As a result, CEE energy-intensive manufacturing firms cut energy consumption and jobs, while substituting their own production with cheaper energy-intensive imports. Even if currently energy prices have decreased, there is the possibility that they will rise again next winter, when energy demand will rise again.

The overall situation of the CEE with regard to its energy security is positive, since storage facilities in the region have reached an adequate level, and the CEE has reduced its dependence on Russia. However, CEE countries have to ensure energy price stability for their industrial sector. This is especially important in view of the upcoming winter, when energy demand will rise again. In order to avoid such a scenario, CEE countries have to increase their diversification efforts to expand the number of reliable gas suppliers. This will not be an easy task, especially for landlocked states in the region such as Hungary and Slovakia.

Oil sanction circumvention - the need to shift the focus on sanction implementation

In June 2022, the Geneva-based company Paramount Energy & Commodities SA stopped its activities, and opened an identical company in Dubai under the name of Paramount Energy & Commodities DMCC. Until the relocation, Paramount SA was a small business specialising in trading Russian crude. In the two months following the beginning of the Ukraine War in February 2023, the Swiss company purchased 11.7 million barrels of oil, making it the fourth global largest buyer of Russian crude following only the industry giants Litasco, Trafigura, and Vitol. Its founder, Niels Troost, a Dutch citizen, used to be a tennis partner of Gennady Timoshenko, founder of the multinational commodity trading company Gunvor and close associate of Vladimir Putin. Following the price cap of $60 a barrel introduced in December 2022 by the G7 on Russian crude oil, the newly established Paramount Energy & Commodities DMCC kept trading the same oil it used to trade when it was based in Geneva, at a price above $70 a barrel, thus higher than the price cap. However, nowadays it is using United Arab Emirates lenders and ships registered to companies based in China, India and the Marshall Islands, countries that have not imposed sanctions on Russia. This allows it to bypass the current G7+ sanctions, which prohibit companies or individuals from the US, EU, UK and Switzerland from trading, shipping and insuring Russian oil sold at a price above the price cap. The Russian producers that sell oil to Paramount DMCC are Rosneft, Gazpromneft and Surgutneftegas, all sanctioned by G7 and EU countries. The main buyers are located in China, which after the beginning of the war has boosted its imports of Russian oil, counting on its increased bargaining position vis-à-vis Moscow to obtain lower-than-market prices. For this reason, officials from the EU, US and UK have visited the UAE to press Emirati authorities to curb sanctions’ circumvention.

This is not just related to oil. Another cause of concern for the G7 is the so-called “re-export” of high-tech goods, where electronic items are first exported from Western countries to the UAE or Central Asian states, and then, as a second step, from those countries to Russia. This is why last year there was a more than seven-fold increase in the UAE’s export of electronic parts such as microchips and drones from the UAE to Russia, while exports from the EU and the US to Armenia and Kyrgyzstan surged by 80% from May to June 2022.

The activity of companies such as Paramount DMCC risks jeopardising the objective of G7’s price cap of slashing the Kremlin’s oil revenue and reducing global energy prices, but without completely blocking Russian oil flows to Europe. These companies contribute to selling Russian crude at prices well above the price cap and they are also diverting oil flows away from European markets. The CEO of the maritime data company Windward, Ami Daniel, reported witnessing numerous cases in which individuals from countries including the United Arab Emirates, India, China, Pakistan, Indonesia, and Malaysia purchased ships to establish a non-Western trade structure with Russia. At the same time, Russia is using Iran’s “ghost fleet” to bypass G7’s price cap. This consists of vessels that disguise their ownership and their movements by turning off satellite trackers or transmitting fake coordinates. These vessels also transfer Russian oil between ships in international waters, all with the aim of concealing the origin of the crude and selling Russian crude at a higher price than the price cap.

As a result, the IMF forecasted Russian oil exports to remain robust, shifting towards nations that have not enforced the price cap. Overall, despite the sanctions, the Russian economy is expected to grow by 0.3% in 2023. Implementing sanctions effectively is a cat-and-mouse game. G7 and EU countries will need to shift their focus on enforcement to ensure that sanctions achieve their goal of denying the Kremlin’s ability to finance the war.

EU ban on Russian oil products – what will the fallout be?

On February 5th, 2023, the EU imposed a further price cap on Russian petroleum products. This comes after the decision, in December 2023, to set a threshold price for Russian crude oil shipped by sea at $60 per barrel. In particular, the new price cap will apply to “premium-to-crude” petroleum products, such as diesel, kerosene and gasoline, and “discount-to-crude” petroleum products, like fuel oil and naphtha. The maximum price agreed on by EU leaders for the former is $100 per barrel and the latter, $45 per barrel. The move is being undertaken by the EU and other G7 countries. This spotlight will focus on the fallout of the price caps on oil products.

Firstly, Russia, which is the second largest oil exporter in the world, will see a decrease in its fiscal revenues in the coming months. Earnings from oil and gas-related taxes and export tariffs accounted for 45 percent of Russia’s federal budget in January 2022. Contrary to embargoes, the price caps implemented by the EU ensure Russian oil products keep flowing into the market, whilst starving Moscow of revenue. In January, Russia’s government revenues decreased by 46 percent compared to last year and government spending surged due to higher military spending. A study by the Centre for Research on Energy and Clean Air reported that Russia is already losing $175 million a day from fossil fuel exports. The new price caps enforced in February will likely reinforce this trend and contribute to the widening Russian deficit, which was $25 billion in January. In response, the Kremlin might increase the shift of its oil product exports to China, India, and Turkey, which collectively now make up 70% of all Russian crude flows by sea and have so far contributed to partly offset the impact of Western sanctions on the Russian economy. At the same time, Moscow might scale up its efforts to bypass price caps imposed by G7 nations through its growing “ghost fleet”, which in January moved more than 9 million barrels of oil. However, these new importers have acquired considerable leverage vis-à-vis Russia. As Adam Smith, former sanctions official with the US Treasury Department, put it “Am I going to buy oil at anything above [the price cap], knowing that’s the only option Russia has?”. This might mean that, even if the Kremlin succeeds in re-orienting its exports of oil products to these new destinations, it will do so at lower prices.

On the other hand, the EU may face a diesel deficit in the coming months. In 2022, Russia accounted for almost half of the EU’s diesel imports, corresponding to around 500,000 barrels per day of the fuel. This will push European countries to try to step up imports of diesel from the US and the Middle East in order to avoid a spike in diesel prices. High fuel prices are politically sensitive and have contributed to high inflation rates across the EU. New trade flows in oil products from these regions could lead to a spike in clean tanker rates, which would increase delivered fuel costs in Europe. Tanker rates from the Middle East to the EU were already close to a three-year high at $60/tonne in January. They are expected to double this year. Moscow has responded to the EU price caps by cutting its oil output by 5 percent, or 500,000 barrels a day. Headline inflation in the eurozone has decreased for the third consecutive month in January but the threat of a rebound in inflation in the near future still looms large.

In such a case, the prospects for an increase in social tensions would become more concrete. Already in September of last year, due to the rising cost of living, protesters in Rome, Milan, and Naples set fire to their energy bills in a coordinated demonstration against escalating prices. In October, thousands of people marched through the streets of France to express their dissatisfaction with the government's inaction regarding the cost of living. In November, Spanish employees rallied together chanting "salary or conflict" in demand of higher wages. However, an increase in salaries would risk pushing up prices even more, thus jeopardising the European Central Bank’s efforts to bring inflation under control.

Potash supply in a de-globalising world

International sanction regimes are disrupting supply chains across the world. In this research paper, analysts from London Politica’s Global Commodities Watch (GCW) provide an overview of the major stakeholders, critical infrastructure, trade routes, supply and demand side risks, and forecasted trends for potash.

Potash is a fertiliser, essential for increasing agricultural yields and feeding the growing population of the world.