Australian Mining in Crisis: Nickel’s Price Plunge

On February 16th, Australia added nickel to its Critical Minerals List to protect its mining industry from strong competition from low-cost Indonesian nickel. Indonesia’s nickel industry is expected to continue growing, backed by pursuant investments from China. Australia’s inclusion of nickel makes the mineral eligible for a 3.9 billion-dollar fund to support the minerals industries linked to the energy transition through grants and loans with low-interest rates. This inclusion is a response to the persistent downward trend of nickel prices that began at the end of 2022, caused by an increase in the supply of cheaper nickel produced in Indonesia. Nickel is used to manufacture batteries for electrical vehicles (EVs) and stainless steel. However, the low-profit margin of nickel exploitation, in combination with increased competition from Indonesia, is jeopardising the Australian mining industry and pushing investors away from Australian mines.

Chinese Investment Into Indonesian Nickel And Its Impacts On Australia

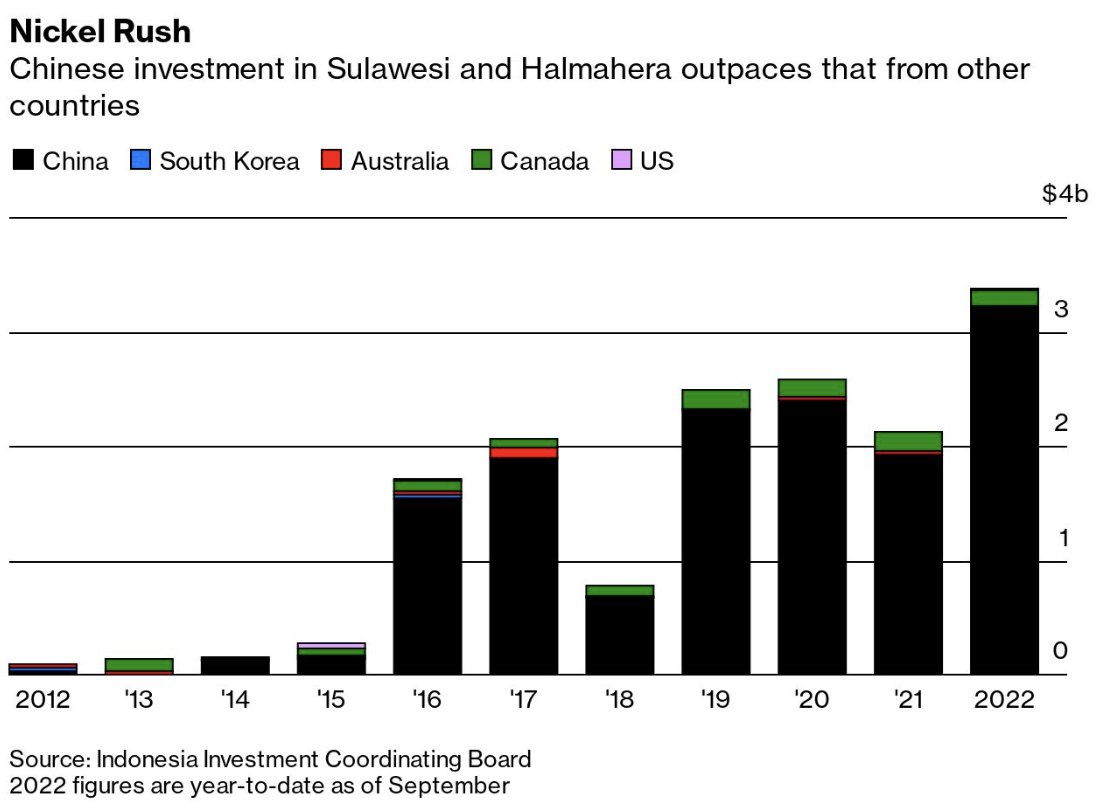

One of the biggest reasons for the global decline in nickel prices, which decreased by 45% in the past year, is Chinese investment in Indonesia. In 2020, Indonesia–which holds 42% of the global nickel reserves–reinstated a ban on unprocessed nickel exports to encourage onshore investment in its processing industry. Large multinational companies, such as Ford and Hyundai, invested in ore processing and manufacturing in the archipelago to access its nickel reserves. Indonesian lateritic nickel ore is attractive as it is closer to the surface than the sulphide ore found in Australia or Canada, making the required infrastructure to exploit it significantly cheaper. The sector received massive Chinese investments in various forms, such as refineries, smelters, and metallurgic schools, to develop the industry that had not previously evolved due to the lack of business know-how and financial investments. In 2022, Chinese investments accounted for 94.1% of the total foreign direct investments in the Indonesian reserves, as seen in the “Nickel Rush” chart below. The investments increased quickly after the ban on unprocessed Indonesian nickel in 2014, which was later eased. These investments boosted the production efficiency of Indonesian refined and semi-refined nickel, representing 55% of the world's total nickel supply in 2023 and potentially increasing its market share to 75% by 2030.

The chart can be found here.

The investment inflows towards Indonesian nickel also helped its laterite nickel ore to become more competitive compared to foreign ones. Primary nickel production is divided into two grades: (1) low-grade or Class II, which is used to manufacture stainless steel and found mainly in Indonesia, and (2) high-grade or Class I, which is used in batteries and can be found in Canada and Australia. While Indonesia has an abundant reserve of low-grade nickel, investments in the industry enabled its producers to apply sophisticated methods to upgrade its nickel to a higher grade. With the improved quality, this type of nickel can be used for batteries, after applying high temperature and pressure methods called high-pressure acid leaching (HPAL), allowing the Indonesian nickel to compete with other countries.

Global Challenges Impacting Nickel Demand

From the demand side, China, Europe, and the United States–Australia’s largest nickel importers—are simultaneously experiencing reduced demand for various reasons. The stainless steel market, which accounts for 75% of nickel use, was sluggish in 2023 due to a slow economic recovery in Europe and the US, which are still recovering from pre-COVID levels. Demand is set to increase by 8% in 2024, but the oversupply mutes its effects. As Sino-American tensions grow, China, the biggest EV market, faces deep and complex economic challenges, including a lack of trust from investors and buyers. Europe, the second biggest EV consumer, has seen the end of tax breaks and other government incentives to buy EVs. Moreover, the US’ high-interest rates prevent consumers from taking out loans, including for EV purchases. The combination of these factors is plummeting the aggregate demand for EVs, thus further pushing down nickel prices, an important mineral for EV batteries.

Consequently, Australian nickel mines are becoming uncompetitive at the current price range, with many even shutting down as nickel prices are expected to continue decreasing throughout 2024. The unit cost per ton of Australian nickel is 28% higher than in Indonesia. Also, while nickel prices decreased globally, its Australian production cost has increased by 49% since 2019, driven by rising wages. The London Metal Exchange (LME) listed nickel closed at US$16.356 per metric ton on February 16, a downward trend since its peak of around US$33,000 per metric ton in December 2022, as seen in the chart below. Companies such as IGO, First Quantum, and Wyloo Metals, some of the most prominent actors in Australian nickel mining, have pulled back investments or suspended part of their businesses.

Chart made by the author with data from Investing.com

These recent developments threaten the jobs of many Australian workers. BHP, the largest Australian mining company, recently announced it may take an impairment charge of around US$3.5 billion. The company plans to shut down its Nickel West division, which employs nearly 3,000 people. In total, the Australian nickel industry supported 10,000 jobs in 2023.

The situation is not exclusive to Australia. Eramet, a French mining company, lost 85% in revenue in 2023 in its New Caledonia nickel plant without any prospect of having government aid to increase its competitiveness. Macquarie, an asset management firm, estimates that 7% of the total nickel production has been removed due to closures. Even so, Australia will likely be the most affected. The country has 18% of global nickel reserves, but it is no longer competitive and is left contemplating the potential of its uncompetitive reserves.

The Debate Over 'Dirty' vs 'Clean' Nickel

There may be a solution to Australia’s nickel problem beyond access to the Australian Critical Mineral Facility Fund. Australian nickel producers are subjected to more strict sustainable standards than Indonesia, increasing costs. The refining of Australian nickel produces six times fewer emissions than other countries, including Indonesia. For these reasons, Madeleine King, the Australian Resources minister, urged the LME to split the listing of nickel into two categories: “dirty” coal-produced nickel and “clean” green nickel. Mining businessmen also demand this separation to motivate buyers to pay a premium for Australian and other nickel supplies with a smaller carbon footprint to level the competition against Indonesian nickel with this premium. This type of split in mineral contracts already exists, such as for aluminium and copper.

LME officials also declare that classifying minerals according to ESG criteria is a tough challenge given the lack of a universal ESG standard. Currently, carbon emissions per ton of the nickel listed in the LME vary greatly, from 6 to 100 tons of carbon dioxide per ton of nickel produced, and the lack of a standard makes it difficult to estimate the absolute emissions that would classify a nickel as “clean”. Currently, the LME classifies low-carbon nickel as producing less than 20 tons of carbon dioxide per ton, and it is working on a more precise definition with nickel specialists.

Reshaping the Australian nickel industry

It is unlikely that the LME will list green nickel separately from “dirty” nickel soon, given the liquidity threats this incurs. The broker wants to solidify buyers' confidence after the 2022 nickel episode before making changes that can jeopardise liquidity. LME officials stated in mid-March of this year that they have no plans to do so as the market size of a green nickel is not large enough to split it. On the other hand, Metalhub, a digital broker, recently started to split its nickel listing with the support of the LME. MetalHub allows the producers to have an ESG certificate tailored to their emissions per ton, which is more flexible than the LME ESG standards. The demand for the “clean” nickel in the digital broker would determine an index price used to derive the premium for this product type and delimit the liquidity of this trade contract. The digital broker plans to release the contract data when the volume traded increases.

It will be challenging to see nickel prices at levels that would make Australia's nickel mining industry competitive again. Indonesia is not hiding the fact that it wants to influence market prices with its nickel supply. According to Septian Hario Seto, an Indonesian deputy overseeing mining, the current price allows Indonesian nickel producers to sustain their activities. Also, low nickel prices will lower the costs of its emerging battery industry, completing the strategy to build an Indonesian upstream industry of batteries.

The access to Australia’s Critical Minerals Facility fund, in combination with the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) from the US, brings the expectation of an increase in investment towards the nickel industry. The Australian fund will be crucial to leverage projects to reduce costs by increasing productivity and infrastructure efficiency related to high costs such as energy, water, high-skilled labour, and transport. Also, the US’ IRA is set to increase the demand for Australian nickel, as it obliges US industries to purchase 40% of its critical minerals needs from either domestic producers or countries with which the US has a free trade agreement–wherein Australia is one of them. The two, combined with ever-evolving environmental regulations leading to a greater demand for EVs, can bring the required financial boost for Australia’s upstream nickel production. However, it will be more difficult for its nickel downstream industry given internal inflation and external competition not only from Indonesia but from all the countries building plans to rebuild their national processing industries.

When it comes to nickel buyers, assuming standard market incentives, they will pay more if they see an advantage in buying a cleaner metal, such as government subsidies or a bigger profit margin on selling a greener EV. Summing up, Australia chose to include nickel in its Critical Minerals List, assuming a big part of the responsibility to protect the industry. The government is one of the stakeholders with the financial ability and the incentive to avoid adverse socioeconomic developments. Minister King is also working with counterparts to advocate for robust standards in production to be reflected in a price premium. These counterparts–namely the US, the EU, and Canada–have the same interest in building an alternative supply chain to the Chinese one. The combination of factors such as the Critical Mineral Facility Fund, the IRA, and a possible stable price premium will give much-needed relief to persisting uncompetitive problems faced by Australian nickel producers. This seems to be the beginning of a pathway towards enhanced competitiveness for Australian nickel miners and, possibly, more sustainable nickel standards.

Even so, more funds might be insufficient to make the Australian nickel miners more competitive. Indonesia has a competitive advantage with a low production price that incurs high costs to its citizens. Coal mines are being constructed to fuel energy-intensive activities to upgrade the Indonesian nickel, making the country reach record levels of coal consumption and carbon emissions. Rivers are contaminated with heavy metals from the mines and refineries, exposing inadequate waste disposals. Addressing these environmental and social costs will level up Indonesian nickel prices, indirectly benefiting Australia and promising relief for the communities burdened by these impacts.

2024 Elections Report: Risks & Opportunities for Commodities Sector

In the ever-evolving landscape of global commodities, the year 2024 stands as a pivotal juncture marked by transformative elections across diverse regions. As nations prepare to cast their ballots, the outcomes hold the power to shape policies and strategies that will significantly influence energy, trade relations, and resource management worldwide.

This report encapsulates the intricate intersections between political shifts and their repercussions on the commodities sector. London Politica’s Global Commodities Watch has made a selection of the most significant countries, and analysed the potential impact of elections based on election programmes, past policies, and scenario planning.

Adding palm-oil to the fire: Malaysia’s proposed ban of palm oil exports to the EU

On 9 January 2023, both Malaysia and Indonesia’s heads of government agreed to work together to “fight discrimination against palm oil”, in a reference to new European Union anti-deforestation legislation. Tangibly, the Malaysian plantation and commodities minister is threatening a wholesale ban on palm oil exports to the EU. Given that Malaysia and Indonesia combine for more than 80 per cent of the world’s palm oil supply and the EU is their third-largest market, the potential ramifications for any such moves would be significant.

How has an issue over palm oil trade reached such a point? For years, Malaysia and Indonesia have railed against EU import barriers on their palm oil, which they characterise as protectionist in favour of the EU’s domestic vegetable oil sector. The EU’s new law, which is expected to be implemented late 2024, obligates “companies to ensure that a series of products sold in the EU do not come from deforested land anywhere in the world” and is aimed at reducing the EU’s impact on biodiversity loss and global climate change. Whilst no country or commodity is explicitly banned, the new regulation covers palm oil and a number of its derivatives. Currently, both Malaysia and Indonesia have separate lawsuits at the World Trade Organization (WTO) pending over the EU’s palm oil trade restrictions.

Implications

To date, only Malaysia has explicitly threatened to ban palm oil exports to the EU. Were this issue to escalate and Malaysia to impose the suggested ban, it would have several consequences. First and foremost, Malaysia’s palm oil industry and wider economy would be hit; the industry makes up 5 per cent of Malaysian GDP, of which a non-negligeable 9.4 per cent of its exports are bought by the EU. Additionally, an abrupt ban is likely to harm producers who have contracts to sell in the EU. Alternative export destinations could be found, especially in food-importing markets such as the Middle East and North Africa, but these producers would struggle to pivot in the short-term and likely see financial losses. Even greater disruptions would be experienced by the few Malaysian palm oil companies that have established refineries in Europe, necessitating a reorientation in their supply chains. Yet the outlook is not entirely negative; palm oil’s lower cost as compared to its substitutes such as soybean oil or sunflower oil will sustain global demand. Overall the Malaysian export ban to the EU would cause a limited scope of economic damage in the short-term, and would see gradually less impact as time progresses and firms adjust.

The potential implications for the EU are equally significant. Firstly, if Malaysia were to enact an export ban soon, this would likely be in unison with Indonesia as the larger producer. A unilateral Malaysian palm oil export ban to the EU, with new regulations permitting, would simply lead EU imports to shift to Indonesia along with profits - hence Malaysia is seeking bilateral action. A joint ban on exporting to the EU would cut the EU off from around 70 per cent of its palm oil, meaning significant interruptions in processed food or biofuel production. New import regulations, however, will help the EU’s domestic vegetable oil sector, which is something that Malaysia asserts. Especially in biofuel production, oils such as soy, canola, and rapeseed would fill the palm oil gap and increase their respective market shares. This issue is further complicated by the EU and Indonesia seeking an elusive free-trade agreement, with negotiations routinely stalled by the EU’s palm oil regulations. This could be in the EU’s favour as free-trade negotiations would break Indonesian-Malaysian solidarity on the issue.

Ironically, the EU’s new regulation could also result in greater amounts of deforestation, instead of less. As the EU reduces its palm oil imports through stricter environmental regulations, Malaysian and Indonesian exports would shift even more to the two larger importers in India and China, with less stringent environmental regulations. The EU’s citizens may not be as directly responsible for deforestation, but worldwide deforestation may in fact increase as a result of this policy.

Market forecast

The immediate reaction from markets was nonplussed. Traders don’t see the threat of an export ban from Malaysia holding. This is reflected in palm oil futures contracts (FCPO: Bursa Malaysia Derivatives Exchange, the benchmark for palm oil), where prices remained stable since the EU’s law was proposed and Malaysia’s threat issued. This means the ban is currently not taken seriously, with Malaysian threats interpreted as a knee-jerk reaction. In any case, firms are anticipating decreased demand from the EU and have been exploring new markets to offset potential European losses. If this Malaysian export ban to the EU were to happen, this would nonetheless pale in comparison to the supply shocks experienced in 2022. A brief ban on all Indonesian palm oil exports globally in April 2022, amidst fears of food shortages and high domestic prices, resulted in record-high global prices. This is a level we are unlikely to see again, as stability returns.

On the supply-side the Malaysian Palm Oil Council expects production to recover in 2023 with estimates of a 3-5 per cent increase, after three years of decline amidst labour shortages linked to COVID-19. This is likely to have a greater impact on global markets instead of a ban or the threat of one, and both Malaysia and Indonesia’s output will continue to climb in the years to come.

Forecasting the demand side is more uncertain. Short-term projections suggest lower demand due to China’s surge of COVID-19 infections post-Lunar New Year, but this is more symptomatic of the wider Chinese economic reopening which will, on balance, stimulate demand. In the medium-term, the threat of recession facing the global economy will hurt palm oil demand, with a mild recession expected in the first half of 2023 followed by a gentle recovery. A longer-term positive outlook is observed in relation to biodiesel’s potential. Amidst high crude oil prices, the further development of biodiesel utilising palm oil would incite new demand.

Looking ahead, projections are uncertain given factors such as the Malaysian migrant worker shortage, the Chinese economy reopening, and potential global recession. This is in addition to Malaysia and Indonesia’s unpredictable regulatory environment, where any policy is subject to rapid change. Palm oil exports to the EU are likely to remain a point of contention between the two south-east Asian countries and their European counterparts. Because palm oil forms a significant part of Malaysia and Indonesia’s economies, their respective governments will continue to intervene.

As the two largest producers in this market potential cooperation between Malaysia and Indonesia over an EU export ban must be monitored- acting together would result in greater consequences for EU imports and worldwide prices. While the Malaysian threat to ban exports to the EU may be an empty one, decreased EU palm oil imports will be observed as it shifts towards more sustainable consumption. Combating climate change is the EU’s underlying aim, but this will necessitate a change in trade patterns.

Indonesia and the possibility of Russian oil

In an interview given to the Financial Times in September 2022 Indonesian President Joko Widodo, said his country needs to look at “all of the options” as it contemplates buying cheap Russian oil to deal with rising energy costs. This extraordinary measure would be the first time in six years that Indonesia imports any oil from Russia. As it concerns south-east Asia’s largest economy, the potential ramifications are significant.

Why is Indonesia’s government considering this?

Amidst the global inflationary environment, the Indonesian government recently cut its fuel subsidy by 30%, therefore increasing consumer fuel prices by a large margin. The higher price of oil since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine means the Indonesian government has spent ever greater amounts for the benefit of consumers. In order to control this swelling subsidy budget Widodo took the unpopular decision to decrease government support for fuel, leading to a series of demonstrations and protests.

With conflicting aims of limiting the increase in budget expenditure on the one hand whilst responding to public opinion for lower prices at the pump on the other hand, it is no small wonder the Indonesian government is considering buying cheaper oil. Jokowi says “there is a duty for [the] government to find various sources to meet the energy needs of the people”. Moscow offering discounted oil at 30% lower than the international market rate has therefore become an attractive solution.

Russia is left with no choice but to sell cheaper oil due to western sanctions, a situation which will worsen if and when the much-rumoured G7 price cap on oil is implemented. From December 5th onwards the EU and the UK will impose a price cap on Russian oil shipped by tankers or else prohibit their transport. This move is already giving India and other significant importers of Russian oil leverage in negotiating oil price discounts, an advantage Indonesia would benefit from.

Are there alternatives?

Yet alternative options do exist. In particular the sale of State-Owned Enterprises (SOEs) could fill the hole left in the Indonesian government’s energy budget. Partially privatising the government oil group Pertamina is being mulled, with the firm’s geothermal branch expecting its IPO before the end of the year. With its $606 billion SOE sector equivalent to half the country’s gross domestic product, the fiscal incentives for such actions are strong.

The government is also attempting to upgrade ageing refineries, in particular through a controversial partnership with Russian state energy company Rosneft. One of the projects, the Tubang Oil Refinery and Petrochemical Complex, is expected to cost $24 billion and will increase Indonesia’s crude refining capacity by 300,000 barrels a day. In the context of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, continued dealing with Russian SOEs poses its own complications in navigating western sanctions.

Risks and Outlook

The foremost risk with purchasing Russian oil comes from American warnings of sanctions for those involved in buying Russian oil using western services. With 80 per cent of global trade denominated in US Dollars, this could be difficult to avoid. The mere threat of such sanctions would affect the appetite of international investors, crucially regarding Indonesian government bonds. In the context of monetary tightening, this is a strong deterrent.

Yet the Indonesian government might follow the Indian model. Russia has recently become India’s largest supplier of oil, as India cashes in on the considerable price discounts offered. Yellen, the American treasury secretary, indicated that the US would allow purchases to continue as India negotiates even steeper discounts due to the western price cap. Monitoring the Indian case could prove fruitful as a bellwether for economic success and international reactions. However, the Indian government is less dependent on international investors' bond buying to fund its budget deficit meaning Indonesia’s risk exposure towards this is of greater importance

The Indonesian government will carefully study these options. Partially listing SOEs or increasing domestic refined supply may not make up the government’s budgetary hole without large-scale changes to the local economy. In the short term, Indonesia handing over its G20 presidency and shortly assuming the ASEAN one may factor into its decision.

In the long term, this temptation of Russian oil will remain. There are clear economic benefits to this by solving the conflicting aims of limiting budget expenditure while keeping consumer prices low. Furthermore, the United States’ tacit green light on buying Russian oil towards similarly developing countries minimises the chances of international reprimands.

This is reinforced by arguments often used against European countries to not buy Russian oil or gas holding little relevance in Indonesia. Notions of ‘supporting Putin’s war’ are of little geopolitical relevance to Indonesia if grain flows from Ukraine stay constant.

The likelihood that Indonesia will begin buying Russian oil is low. The scale of risks involved, particularly regarding sanctions, will dissuade the Indonesian government. The spate of interviews given in September from Indonesia's energy minister and President were likely moves to test the waters among investors and the international community. This decision is of course subject to rapid change given Indonesia’s unpredictable regulatory environment where policies can change on a dime.

The dilemma faced by Indonesia means that south-east Asia’s largest economy is firmly in the camp of countries calling for a rapid resolution to the Russia-Ukraine conflict.