The LNG Freeze Limbo: How the US Export Pause is Reshaping Global Gas Dynamics

The Biden administration recently suspended granting permits for new liquified natural gas (LNG) imports, which will likely have major impacts on global energy security, especially for the European Union (EU). The move comes amidst growing protests against the Biden administration over its lacklustre plan to make a swift transition to green energy ecosystems. As per the White House, the decision aims to address domestic health concerns, such as increasing pollution near export facilities. However, the timing of the decision raises serious concerns, especially as the US’ European allies grapple with energy shortages since the Russian invasion of Ukraine 2 years ago.

The EU has been greatly dependent on LNG exports from the US in dealing with energy shortages following its decision to stop Russian exports. For instance, in the first half of 2023, the US exported more liquefied natural gas than any other country – 11.6 billion cubic feet a day. That same year, 60 per cent of US LNG exports were delivered to Europe and 46 per cent of European imports came from the US. This abrupt decision by President Biden, prioritising domestic concerns over international energy security and stability, is a long term challenge for US allies in Europe, as well as in Asia.

Despite the EU having fairly dealt with the energy shortages, a potentially long, harsh winter season later this year could further complicate the entire scenario, given the strong correlation between weather and gas prices. Winter conditions are, thus, likely to increase LNG demands, thereby increasing gas prices. Hence, shutting down gas exports to Europe is likely to accelerate geopolitical risks. This would imply diverting economic supply by the EU for Ukraine to deal with the impending energy crisis.

Many of the developing economies in Asia have traditionally been heavy consumers of coal and fossil fuels, primarily due to a lack of infrastructural capabilities to harness renewable sources of energy. Early LNG developments, especially in South East Asia were spurred on by the 1973 oil shock, which brought the need to diversify away from Middle Eastern oil for power generation. Consisting of many developing economies, countries in Asia wanted to rely on a stable and efficient partner to develop their energy ecosystems running on a fair share of LNG exports. Being the largest exporter of LNG in the world, the US was seen as “the reliable partner.” Hence, the recent announcement by the White House has been taken seriously in Asia, given that it might hinder the progress of capacity expansion projects in the region.

Moreover, one of the US’ strategic allies in the region, Japan, could be hit extremely hard by the recent development, given that it is the world’s second-largest purchaser of LNG, with a huge proportion of the imports coming from the United States. Several Japanese companies, especially JERA, have been foundation buyers of LNG export projects and this announcement is likely to hinder their business prospects in the present and the future. Moreover, the future implications of the pause are even more disastrous for the other allies of the US, especially smaller countries like the Philippines, which is currently undergoing energy shocks. The Philippines relies heavily on the electricity and natural gas acquired from the Malampaya gas field. This reserve is expected to run dry in 2027, causing an energy crisis. The nation must now choose between transitioning to renewable energy or continue to rely heavily on the exploration of conventional energy sources which would make them drift further apart from their commitments towards cutting down carbon emissions. The leadership in Manila initially looked to the United States to provide initial relief over its impending energy crisis by importing LNG reserves from the US. However, the latest White House decision will very well make the Philippines’ political leadership exhibit signs of perplexity and look for other alternatives as the Southeast Asian nation continues to grapple with an ongoing energy crisis which is likely to turn worse in the upcoming years.

While the decision might highlight the US’ decision to deal with environmental concerns and climate change issues, the abruptness of the decision is likely to raise serious doubts among the allies over Washington’s reliability to help them cope with the ongoing energy crisis, made worse by a sluggish global economy in the aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic. The move is likely to lead its partners to export LNG from other countries, which have a higher profile of emitting carbon emissions than the US.

This may also prompt countries to rely heavily on the use of coal and fossil fuels, thereby reversing the trend of actively exploring cleaner energy alternatives. With the global community facing an incoming climate emergency, substantial hope was placed on developed, industrialised countries of the north to create a strong base for the developing economies of the global south to make a transition towards cleaner energy ecosystems.

The US, with one of the largest reserves and the largest exporter of LNG, was seen as the “responsible leader” to effect this transition and, at the same time, stand shoulder to shoulder with struggling economies to deal with the contemporary energy shortage predicament. With ongoing geopolitical crises, the perception of the “pause” being indicative of breaking commitments to international partners and allies, cannot be undermined, in a year that is likely to decide the fate, political will, and the “ability to lead home and abroad amidst challenges” of the incumbent US president.

Featured image by Maciej Margas: PGNiG archive, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=90448259

A Strait Betwixt Two

As the Yemeni Houthi group's assault on maritime vessels continues to escalate, the risk to key commodity supply chains raises global concern. As analysed in this series' previous article (available here), conflict escalation impacts the region's security, impacting key trade routes and global trade patterns. The Suez Canal is a key trade route whose stability and security could impact and shift trade dynamics. As the search for alternative trade routes ensues, the Strait of Hormuz makes use of a power vacuum to expand its influence.

Suez Canal

The Suez Canal is a 193-kilometre waterway that connects the Red Sea to the Mediterranean Sea. Approximately 12% of global trade passes through the Canal, granting it vast economic, strategic, and geopolitical influence on a global scale. This canal shortens maritime trade routes between Asia and Europe by approximately 6,000 km by removing the need to export around the Cape of Good Hope and serves as a vital passage for oil shipments from the Persian Gulf to the West. Approximately 5.5 million barrels of oil a day pass through the Canal, making it a ‘competitor’ of the Strait of Hormuz.

Global trade via the Suez Canal is likely to decrease as a result of the rising tensions near the Bab el-Mandeb Strait. Due to their geographic predispositions, the Bab el-Mandeb Strait and the Suez Canal are interdependent; bottlenecks in either trade choke point will have a knock-on effect on the other. Bottlenecks caused by Houthi aggression against ships in the strait are likely to redirect maritime traffic from the Suez Canal to alternative passageways. From November to December 2023, the volume of shipping containers that passed through the Canal decreased from 500,000 to 200,000 per day, respectively, representing a reduction of 60%.

Suez Canal Trade Volume Differences (metric tonnes)

The overall trade volume in the Suez Canal has decreased drastically. Between October 7th, 2023, and February 25th, 2024, the channel’s trade volume decreased from 5,265,473 metric tonnes to 2,018,974 metric tonnes. As the weaponization of supply chains becomes part of regional economic power plays, there is a global interest in decreasing the vulnerability of vital choke points via trade route diversification. The lack of transport routes connecting Europe and Asia has hampered these interests, making choke points increasingly susceptible to exploitation.

Oil Trade Volumes in Millions of Barrels per Day in Vital Global Chokepoints

Source: Reuters

Quantitative Analysis

Many cargoes have been rerouted through the Cape of Good Hope to avoid the Red Sea region since the beginning of the Houthi conflict. Several European automakers announced reductions in operations due to delays in auto parts produced in Asia, demonstrating the high exposure of sectors dependent on imports from China.

In the first two weeks of 2024, cargo traffic decreased by 30% and tanker oil carriers by 19%. In contrast, transit around the Cape of Good Hope increased by 66% with cargoes and 65% by tankers in the same period. According to the analysis of JP Morgan economists, rerouting will increase transit times by 30% and reduce shipping capacities by 9%.

Depiction of Trade Route Diversion

Source: Al Jazeera

More fuel is used in the rerouted freight, an additional cost that increases the risk of cargo seizure and results in elevated shipping rates. The most affected routes were from Asia towards Europe, with 40% of their bilateral trade traversing the Red Sea. The freight rates of the north of Europe until the Far East, utilising the large ports of China and Singapore, have increased by 235% since mid-December; freights to the Mediterranean countries increased by 243%. Freights of products from China to the US spiked 140% two months into the conflict, from November 2023 to January 25, 2024. The OECD estimates that if the doubling of freight persists for a year, global inflation might rise to 0.4%.

The upward trend in freight rates can be seen in the graphic pictured below, depicting the “Shanghai Containerised Freight Index” (SCFI). The index represents the cost increase in times of crisis, such as at the beginning of the pandemic, when there were shipping and productive constraints, and more recently, with the Houthi rebel attacks. Most shipments through the Red Sea are container goods, accounting for 30% of the total global trade. Companies such as IKEA, Amazon, and Walmart use this route to deliver their Asian-made goods. As large corporations fear logistic and supply chain risk, more crucial trade volumes could be rerouted.

Shanghai Containerized Freight Index

Energy Commodity Impact

Of the commodities that traverse the Red Sea, oil and gas appear to be the most vulnerable. Before the attacks, 12% of the oil trade transited through the Red Sea, with a daily average of 8.2 million barrels. Most of this crude oil comes from the Middle East, destined for European markets, or from Russia, which sends 80% of its total oil exports to Chinese and Indian markets. The amount of oil from the Middle East remained robust in January. Saudi oil is being shipped from Muajjiz (already in the Red Sea) in order to avoid attack-hotspots in the strait of Bab al-Mandeb.

Iraq has been more cautious, contouring the Cape of Good Hope and increasing delays on its cargo. Iraq's oil imports to the region reached 500 thousand barrels per day (kbd) in February, 55% less than the previous year's daily average. Conversely, Iraq's oil imports increased in Asia, signalling a potential reshuffling of transport destinations. Trade with India reached a new high since April 2022 of 1.15 million barrels per day (mbd) in January 2024, a 26% increase from the daily average imports from Iraq's crude.

Brent Crude and WTI Crude Fluctuations

Source: Technopedia

Refined products were also impacted. Usually, 3.5 MBd were shipped via the Suez Canal in 2023, or around 14% of the total global flow. Nearly 15% of the global trade in Naphta passes through the Red Sea, amounting to 450 kbd. One of these cargoes was attacked, the Martin Luanda, laden with Russian naphtha, causing a 130 kbd reduction in January compared with the same month in 2023. Traffic to and from Europe is being diverted in light of the conflict. Jet fuel cargoes sent from India and the Middle East to Europe, amounting to 480 kbd, are avoiding the affected region, circling the Cape of Good Hope.

Due to these extra miles and higher speeds to counteract the delays, bunker fuel sales saw record highs in Singapore and the Middle East. The vessel must use more fuel, and bunker fuel demand increased by 12.1% in a year-over-year comparison in Singapore.

In 2023, eight percent, or 31.7 billion cubic metres (bcm), of the LNG trade traversed the Red Sea. The US and Qatar exports are the most prominent in the Red Sea. After sanctioning Russia's oil because of the Ukrainian War, Europe started to rely more on LNG shipments from the Middle East, mainly from Qatar. The country shipped 15 metric tonnes of LNG via the Red Sea to Europe, representing a share of 19% of the Qatari LNG exports. Vessels travelling to and from Qatar will have to circle the Cape of Good Hope, adding 10–11 days to travel times and negatively impacting cargo transit.

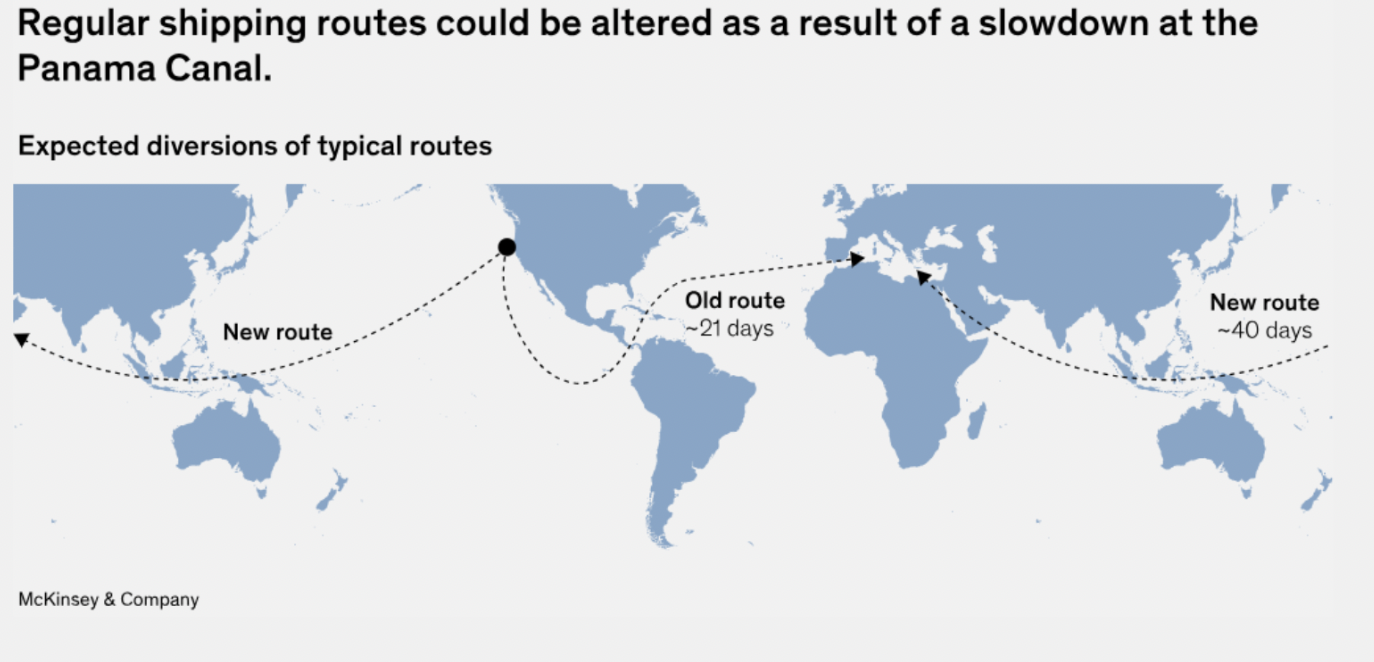

US LNG export capacity has increased in the past few years, sending shipments to Asia via the Red Sea. The Panama Canal receives many LNG cargoes from the US via the Pacific, yet its traffic limitations cause US cargo to be routed through the Atlantic and the Red Sea. The figure “Trade Shipping Routes” below displays the dimensions of the shifts that US LNG cargoes must take in the absence of passage via the Panama Canal.

Trade Shipping Routes

Source: McKinsey & Company

Until January 15, at least 30 LNG tankers were rerouted to pass through the Cape of Good Hope instead. Russia's LNG shipments to Asia are currently avoiding the Red Sea, and Qatar did not send any new shipments in the last fortnight of January after the Western strikes at Houthi targets.

Risk Assessment

A share of 12% of oil tankers, ships designed to carry oil, and 8% of liquified gas pass through this route towards the Mediterranean. Inventories in Europe are still high, but if the crisis persists for several months, energy prices could be aggravated. As evidenced by the sanctions against Russia, cargo reshuffling is possible. Qatar can send its cargoes to Asia, and those from the US can go to European markets, allowing suppliers to effectively avoid the Red Sea.

Around 12% of the seaborn grains traversed the Red Sea, representing monthly grain shipments of 7 megatonnes. The most considerable bulk are wheat and grain exports from the US, Europe, and the Black Sea. Around 4.5 million metric tonnes of grain shipments from December to February avoided the area, with a notable decrease of 40% in wheat exports. The attacks affected Robusta coffee cargoes as well. Cargoes from Vietnam, Indonesia, and India towards Europe were intercepted, impacting shipping prices and incentivizing trade with alternative nations.

Daily arrivals of bulk dry vessels, including iron ore and grain from Asia, were down by 45% on January 28, 2024, and container goods were down by 91%. However, further significant disruptions to agricultural exports are not expected. Most of the exports from the US, a large bulk, were passing through the Suez Canal to avoid the congestion of the Panama Canal due to the droughts that limited the capacity of circulation. These cargoes are now traversing the Cape route.

Around 320 million metric tonnes of bulk sail through Suez, or 7% of the world bulk trade. No significant impacts are predicted for iron ore or coal, which represented 42 and 99 megatonnes of volume, respectively, shipped through the Red Sea in 2023. Most of the dry bulks that traverse the impacted region can be purchased from other suppliers, precluding significant supply disruptions.

As of March 1st, reports show that only grain shipments and Iranian vessels were passing through the Red Sea. There were no oil or LNG shipments with non-Iranian links in the Red Sea. These developments illustrate the significant trade shifts caused by the Red Sea crisis. As of today, a looming threat lies in the Houthis’ promises of large-scale attacks during Ramadan. The lack of intelligence on the Houthi’s military capacity and power makes it difficult to ascertain the extent of future conflicts, generating further uncertainty in commercial trade.

The Strait of Hormuz

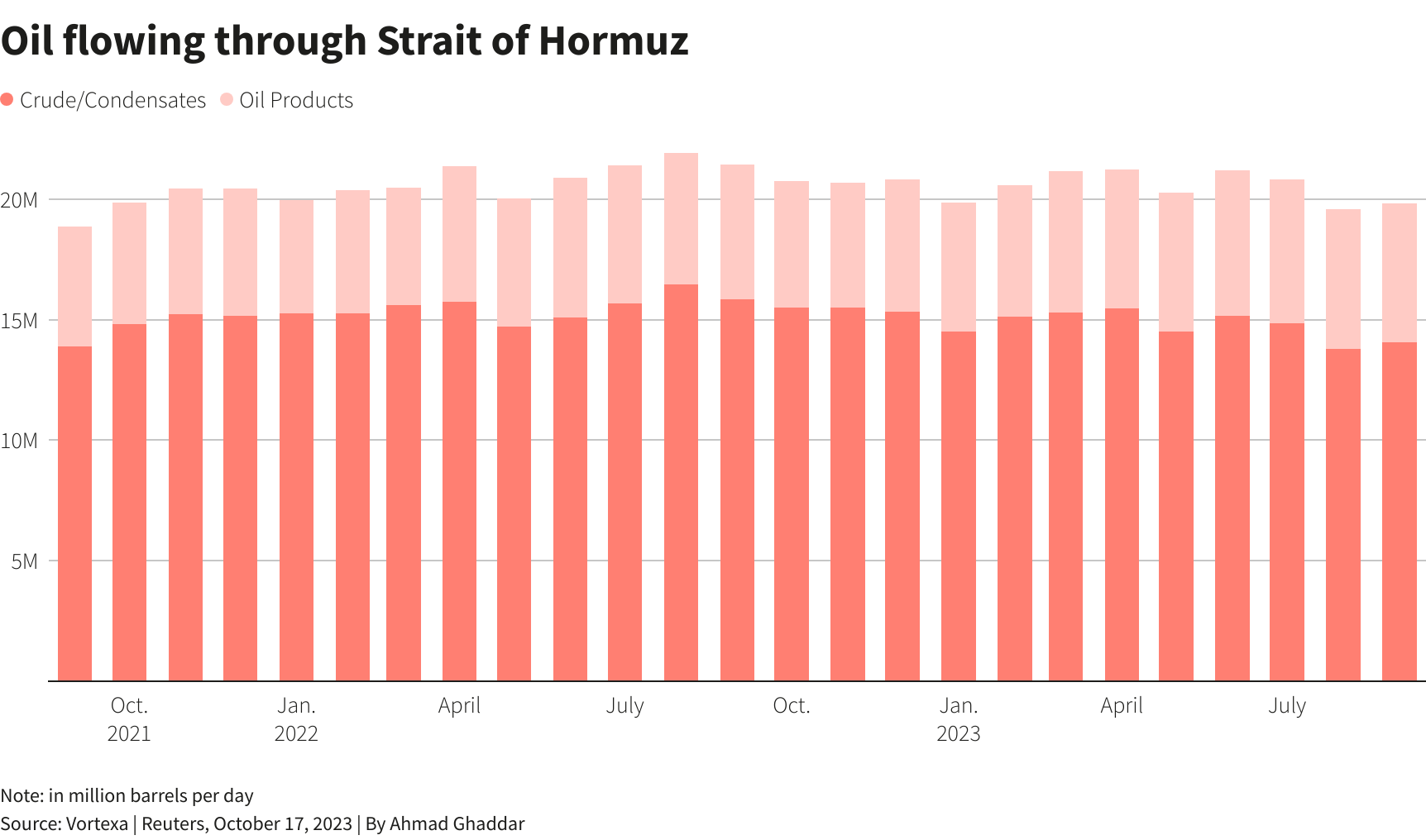

The Strait of Hormuz is a channel that connects the Persian Gulf to the Gulf of Oman, providing Iran, Oman, and the UAE with access to maritime traffic and trade. The strait is estimated to carry about one-fifth of the global oil at a daily trade volume of 20.5 million barrels, proving to be of vital strategic importance for Middle Eastern oil supply the world’s largest oil transit chokepoint. The strait is a prominent trade corridor for a myriad of oil-exporting nations, namely the OPEC members Saudi Arabia, Iran, the UAE, Kuwait, and Iraq. These nations export most of their crude oil via the passage, with total volumes reaching 21 mb of crude oil daily, or 21% of total petroleum liquid products. Additionally, Qatar, the largest global exporter of LNG, exports most of its LNG via the Strait.

Geographic Location of Strait of Hormuz

Source: Marketwatch

Although the strait is technically regulated by the 1982 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, Iran has not ratified the agreement. Through its geostrategic placement, Iran can trigger oil price responses through its influence on trade transit, establishing the country’s regional and global influence.

Strait of Hormuz Oil Volumes

Source: Reuters

Experts are particularly worried that the turbulence is likely to spread to the Strait of Hormuz now that Iran backs the Houthis in Yemen and might want to support their cause by doubling down regionally. However, this is something that would cause a lot of backlash in the form of a further tightening of economic sanctions against Tehran, which might deter further provocations.

Despite Iran’s previous threats to block the Strait entirely, these have never gone into effect. Diversifying trade routes to avoid supply shocks and bottlenecks is of interest to regional oil-exporters dependent on the route for maritime trade access. Such diversification attempts have already been undertaken, as seen by the UAE and Saudi Arabia's attempts to bypass the Strait of Hormuz through the construction of alternative oil pipelines. The loss of trade volume from these two producers, holding the world's second and fifth largest oil reserves, respectively, severely hindered the corridor’s prominence.

The attacks on the Red Sea might cause damage to the oil and LNG cargo from countries in the Persian Gulf, increasing costs for oil and gas exporters. However, cargoes could find alternative destinations. The vast Asian markets, which face a shortage of energy products due to a loss of trade through the Red Sea, could be a potential suitor. Finding new LPG (liquefied petroleum gas) contracts could be beneficial for Iran, and its recently enhanced production capacity could supply various markets.

Geopolitics and Prospects for a Route Shift

Although the Strait of Hormuz stands to capture diverted trade flows from the Suez Canal, its global influence is still limited by Iran’s geopolitical ties. As exemplified by the Iran-US conflict, Iran’s conflicts can severely impact traffic through the Strait, significantly impacting the stability of the route and prospects for future growth.

Although security and stability are of paramount importance to trade, efforts to provide these traits could be counterproductive. On March 12th, China and Russia conducted maritime drills and exercises in the Gulf of Oman with naval and aviation vessels. According to Russia's Ministry of Defence, this five-day exercise sought to enhance the security of maritime economic activities using maritime vessels with anti-ship missiles and advanced defence systems. Over 20 vessels were displayed in this joint naval drill, attempting to lure trade through the promise of stability and security.

Whether meant as a display of power or a promise of security, the pronounced presence of Russian and Chinese forces could aggravate geopolitical tensions and increase the potential for conflict in the region, driving global trade prospects down. With precedents of trade conflict, such as the IRGC’s seizure of an American oil cargo in the Persian Gulf on January 22nd, various countries might be sceptical of rerouting commodity trade through the Strait.

Tensions are also aggravated by Iran’s alleged assistance in the Houthi attacks. The US has supposedly communicated indirectly with Iran to urge them to intervene in the region. China and Russia’s interest in improving the Strait’s trade prospects would benefit from a de-escalation of the Houthi conflict, as shown by China’s insistence on Iran’s cooperation in the Houthi conflict. As the conflict stands, the Strait’s prospect as an alternative trade route is dependent not only on Iran’s reputation and presence in global conflicts but also on the route’s patrons and proponents.

Conclusion

The extent to which the Strait of Hormuz could benefit from trade diversion depends not only on its ability to pose itself as a viable trade route but also on the duration of the Houthi conflict. In order to capture trade volumes and increase international trade through the route, Iran would have to ameliorate its geopolitical ties and provide stability to compete with rising prospective trade route alternatives. Although the conflict in the Suez has yet to show promising signs of de-escalation, securing the Suez would likely cause previous trade volumes to resume and restore its hegemony in commodity trade. It remains to be seen whether the conflict will endure long enough to allow other trade routes to be established as alternatives and permanently shift power balances in global trade.

The U.S. LNG Pause: Implications for the Global Fertiliser and Food Markets

Peter Fawley

The U.S. LNG Pause

On January 26, the Biden administration announced a temporary pause on approvals of new liquified natural gas (LNG) export projects. The pause applies to proposed or future projects that have not yet received authorisation from the United States (U.S.) Department of Energy (DOE) to export LNG to countries that do not have a free trade agreement (FTA) with the United States. This is significant as many of the largest importers of U.S. LNG–including members of the European Union, the United Kingdom, Japan, and China–do not have FTAs with the United States. Without the DOE authorisation, an LNG project will not be allowed to export to these countries. The policy will not affect existing export projects or those currently under construction. The Department of Energy has not offered any indication for how long the pause will be in effect.

This pause will have political and economic implications across the globe, and is expected to apply further pressure to the LNG market, fertiliser prices, and agricultural production. The following analysis will first delve into the rationale for the pause, the expected impact it will have on global LNG supplies, and the associated risks this poses for the fertiliser and food markets. It will then examine the impact of this policy change on India’s agricultural sector, given that the country is heavily reliant on LNG imports to manufacture fertilisers for agricultural production. The article will conclude with brief remarks about the pause.

Reasons for the Pause

According to the Biden administration, the current review framework is outdated and does not properly account for the contemporary LNG market. The White House’s announcement cited issues related to the consideration of energy costs and environmental impacts. The pause will allow DOE to update the underlying analysis and review process for LNG export authorisations to ensure that they more adequately account for current considerations and are aligned with the public interest.

There are also likely political motivations at play, given the upcoming election in the United States. Both climate considerations and domestic energy prices are expected to garner significant attention during the lead up to the 2024 U.S. presidential election. The Biden administration has been under increasing pressure from environmental activists, the political left, and domestic industry regarding the U.S. LNG industry’s impact on climate goals and domestic energy prices. In fact, over 60 U.S policymakers recently sent a letter to DOE urging its leadership to reexamine how it factors in public interests when authorising new licences for LNG export projects.

These groups have argued that the stark increase in recent U.S. LNG exports is incompatible with U.S. climate commitments and policy objectives, as the LNG value chain has a sizeable emissions footprint. Moreover, there is a concern about the standard it sets for future policy. An implicit and uncontested acceptance of LNG could signal that the U.S is wholly committed to continued use of fossil fuels as an energy source, leading to more industry investments in fossil fuels at the expense of renewable energy technologies. In an unusual political alliance, large U.S. industrial manufacturers are lobbying alongside environmentalists to curb LNG exports. These consumers, who are dependent on natural gas for their manufacturing processes, worry that additional LNG export projects will raise domestic natural gas prices. Therefore, the pause may then be interpreted as an acknowledgement of these concerns and an attempt to reassure supporters that the Biden administration is committed to furthering its climate goals and securing lower domestic energy prices.

Impact on LNG Supplies

Since the pause only pertains to prospective projects, there will be no impact on current U.S. LNG export capacity. However, the pause may constrain supply and reduce forecasted global output as the new policy indefinitely halts progress on proposed LNG projects that are currently awaiting DOE authorisation. In the long-term, this announcement has the potential to tighten the LNG market, potentially resulting in increased natural gas prices and other commercial ramifications. Because the U.S. is currently the world’s largest LNG exporter, a drop in expected future U.S. supplies may force LNG importers to seek to diversify their supply. Some LNG buyers will likely redirect their attention to other, more certain sources of LNG, such as Qatar or Australia. Additionally, industry may be more keen to invest in projects in countries that have less regulatory ambiguity related to LNG projects.

Risk for the Global Fertiliser and Food Markets

Natural gas is key to the production of nitrogen-based fertilisers, which are the most common fertilisers on the market. With regard to the use of natural gas in fertiliser production, most of it (approximately 80 per cent) is employed as a raw material feedstock, while the remaining amount is used to power the synthesis process. Farmers and industry prefer natural gas as a feedstock as it enables the efficient production of effective fertilisers at the least cost.

The U.S. pause on new LNG projects is an unsettling signal to already fragile natural gas markets given the existence of relatively tight current supplies and a forecasted shortfall in future supply levels. This announcement will exacerbate vulnerabilities and put increased pressure on global supplies, potentially leading to greater volatility and price escalation. Additionally, increased global demand for natural gas will further strain the LNG market. Therefore, global fertiliser prices may increase given that natural gas is an integral input in fertiliser production. Natural gas supply uncertainty stemming from the U.S. announcement may not only impact market prices for fertiliser, but could also increase government subsidies needed to support the agricultural industry to protect farmers from price volatility. Due to the increased subsidy outlay, government expenditure on other publicly-funded programs could plausibly be reduced.

The last time there was a significant shock to the natural gas market, fertiliser shortages and greater food insecurity ensued. Following the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine, there was a stark increase in natural gas prices, which led to a rise in the cost of fertiliser production. This prompted many firms to curtail output, causing fertiliser prices to soar to multi-year highs. Higher fertiliser costs will theoretically induce farmers to switch from nitrogen-dependent crops (e.g., corn and wheat) to less fertiliser-intensive crops or decrease their overall usage of fertilisers, both of which may jeopardise overall agricultural yield. Given that fertiliser usage and agricultural output are positively correlated, surging fertiliser costs in 2022 translated into higher food prices across the world. While inflationary pressures have subsided in recent time, global food markets remain vulnerable to fertiliser prices and associated supply shocks. This is especially true for countries that are largely dependent on their agricultural industry for both economic output and domestic consumption. Food insecurity and global food supplies may also be further constrained by unrelated impacts on crop yields, such as extreme weather and droughts.

Case Study: India

The future LNG supply shortfall and its impact on fertiliser and food markets may be felt most acutely by India. The country is considered an agrarian economy, as many of its citizens – particularly the rural populations – depend on domestic agricultural production for income and food supplies. Fertiliser use is rampant in India and the country’s agricultural industry relies heavily on nitrogen-based fertilisers for agricultural production. With a steadily rising population and a finite amount of arable land, expanded fertiliser usage will be necessary to increase crop production per acre. As a majority of India’s fertiliser is synthesised from imported LNG, the expected increased demand for fertiliser will necessitate more LNG imports.

LNG imports to India are projected to significantly rise in 2024, with analysts forecasting a year-on-year growth of approximately 10 per cent. Over the long-term, the U.S. Energy Information Administration predicts that overall natural gas imports to India will grow from 3.6 billion cubic feet per day (Bcf/d) in 2022 to 13.7 Bcf/d in 2050, a 4.9 per cent average annual increase. The agricultural industry is a substantial contributor to this growth. This trend is only expected to continue, as India has announced that it plans to phase out urea (a nitrogenous fertiliser) imports by 2025 in order to further develop its domestic fertiliser industry. To ensure adequate supplies for domestic urea production, India is expected to increase its natural gas demand and associated reliance on LNG imports. A recent agreement between Deepak Fertilisers, a large Indian fertiliser firm, and multinational energy company Equinor exemplifies this. The agreement secures supplies of LNG (0.65 million tons annually) for 15 years, starting in 2026.

Concluding Remarks

The U.S. pause on new LNG export facilities will have ramifications for the global natural gas market and supply chain. While current export capacity will not be jeopardised, the policy change will delay future projects and may put investment plans into question. The pause will also have implications for downstream markets in which natural gas is an important input, such as the fertiliser market. There are a couple of questions that now loom over the LNG industry: (1) what will be the duration of the pause; and (2) to what extent will the pause affect LNG markets?

While the U.S. Department of Energy has given no firm timeline for the pause, analysts estimate – based on previous updates – that the DOE review will likely last through at least the end of 2024. The expectation is that the longer the pause remains in effect, the more uncertainty it will create, especially as it relates to private industry investment decisions and confidence in U.S. LNG in the long-term. In addition to the fertiliser and food markets, transportation, electricity generation, chemical, ceramic, textile, and metallurgical industries may all be affected by the pause. One potentially positive consequence is that because LNG is often thought of as a transitional fuel (between coal and renewable energies), a large enough impact on LNG supplies could accelerate the energy transition directly from coal to renewable sources of energy, providing a boost to the clean energy technologies market. However, the pause may also create tensions with trading partners as it could be interpreted as an export control or a discriminatory trade practice, both of which stand in violation of the principles of the multilateral rules-based trading system. This may expose the U.S. to potential challenges and disputes at the World Trade Organization. Although it may be some time before we are provided concrete answers to these questions, the results of the 2024 U.S. presidential election will provide some insight into what LNG policies in the U.S. will look like going forward.

All eyes on Algeria: how natural gas is shaping North-African politics

One country in North-Africa seems to be making the most out of the current energy crisis and a new era in great-power rivalry - Algeria. Great potential has fuelled massive interest in the country’s gas industry and led to a significant increase of gas revenues in the past years. As a consequence, the country is able to spend big, both domestically and abroad, and charter a more active foreign policy. The latter, however, is held under increased scrutiny by parliamentarians and senators across the Atlantic, raising questions about the risks of Algerian gas imports. Another question, which is worth asking, is to what extent Algerian gas potential can be turned into actual export flows.

This analysis will take a deep-dive into 1) the drivers of increased interest and cooperation in Algeria, 2) the outcomes so far, and 3) complications and geopolitical dynamics, after which a small outlook will be presented.

Drivers of increased interest and cooperation in Algeria

Increased interest and cooperation in Algeria and North Africa are partly driven by the war in Ukraine and the need to source new gas supplies. In a bid to curb Russian gas imports, both European and international energy companies are scrambling supplies across the globe. Before the war, Russian natural gas accounted for roughly 45% of EU imports or 155 bcm, whereas it is now standing at roughly 10% of EU imports or 34.4 bcm. That leaves a gap of roughly 120.6 bcm to satisfy demand. And while some supplies may be curbed by lowering demand through the increase of energy efficiency and the usage of other fuels, most will have to be sourced elsewhere.

Algeria, as a source of natural gas, offers much potential. It is Africa’s largest natural gas exporter and in combination with its location, the country could offer an ideal place to source gas. Algeria’s potential has led to increased interests in its gas industry. Other countries in North Africa, including Libya and Egypt, have also received increased interest. Notably, Libya secured an $8 billion exploration deal with Italian energy major Eni.

*Note that the Trans-Saharan and Galsi potential or planned pipelines.

Algerian gas market: Facts and Figures

Reserves: The country holds roughly 1.2% of proven natural gas reserves in the world, accounting for 2,279 bcm.

Production: Its production stands at 100.8 bcm per year.

Exports: In 2021 it exported 55 bcm, 38.9 bcm through pipelines, and 16.1 bcm in the form of LNG. European imports accounted for 49.5 bcm, 34.1 bcm by pipelines, and 15.4 bcm in the form of LNG.

Export capacity: Algeria has a total export capacity of 87,5 bcm: the Maghreb-Europe (GME) pipeline (Algeria-Morocco-Spain) 13.5 bcm, Medgaz (Algeria-Spain) 8 bcm, Transmed (Algeria-Tunisia-Italy) 32 bcm, LNG 34 bcm.

Aside from potential, ambition (on both sides of the Mediterranean) is another reason for interest and cooperation. Interest has come from the EU and several member states, but mostly from Italy. Instead of merely securing gas supplies, Italy aims to become an energy corridor for Algerian gas in Europe. This will boost Italian significance in the European energy market, increasing both transit revenues and investment in its own gas industry. Moreover, Rome seeks to increase its profile in the Mediterranean, mainly to stabilize the region and decrease migration flows. It views both Algeria and its national energy firm Eni as key factors in that aim.

Algeria is also looking for a more active role in the region. For the past years, the country has been emerging from its isolationism, which characterized the rule of president Bouteflika, who was ousted in 2019. With new deals and increased gas revenues it hopes to increase defense and public spending, prop-up its gas industry, which suffered from lack of investment, and stabilize its economy and the region. Aside from economic reasons, therefore, cooperation between the two sides is politically motivated as well.

What has this increased interest and cooperation so far led to?

As a result of increasing gas prices and rising demand, the Algerians have seen their revenues increase massively. Sonatrach, Algeria’s state-owned energy company, reported a massive $50 billion energy export profits in 2022, compared to $34 billion in 2021, and $20 billion in 2020. This will allow for more fiscal space and public spending. In fact, the drafted budget of 2023 is the largest the country has ever seen, increasing 63% from $60 billion in 2022 to $98 billion in 2023. Because of bigger budgets, Algeria will also be able to partly stabilize its neighbors by offering electricity and gas at a discount - something the country is currently discussing with Tunisia and Libya.

The Italian trade looks most promising and has led to multiple deals. Trade between the two countries has doubled from $8 billion in 2021 to $16 billion in 2022, whereas dependence on Algerian gas increased from 30% before the Ukraine war to 40% at the moment. Last year, Eni CEO Claudio Descalzi secured approval from Algeria to increase the gas its exports via pipeline to Italy from 9 bcm to 15 bcm a year in 2023 and 18 bcm in 2024, and last month, Italian Prime Minister Meloni, joined by Descalzi, visited Algeria to build upon that earlier cooperation. Again, two agreements were signed, one with regards to emissions reduction and the other to increase energy export capacity from Algeria to Italy.

The visit and new plans reflected ambitions from both sides. President Tebboune recently announced Algeria’s aim to double gas exports and reach 100 bcm per year and Meloni mentioned a new ‘Mattei plan’ (which refers to Enrico Mattei, founder of Eni, who sought to support African countries' development of their natural resources in order to help the continent maximize its economic growth potential, while facilitating Italian energy security). Furthermore, the Algerian ambassador stated the country’s intention to make Italy a European hub for Algerian gas, whereas Eni CEO Descalzi mentioned the possibility of a north-south axis, connecting the European demand market with the (North) African supply market.

Interest has also led to other plans, potential deals, and rapprochement. Firstly, the EU sees potential and aims to secure Algeria as a long-term strategic partner. Last year, the EU’s energy commissioner visited Algeria as part of “a charm offensive”. Secondly, the Ukraine war and Algeria’s abundance of gas supplies also seems to be the main reason for France’s rapprochement toward Algeria. In addition to this, Slovenia plans to build a pipeline to Hungary to transport Algerian gas as Algeria aims to increase electricity exports to Europe. Algeria’s future as an energy supplier could also go beyond natural gas, as last December German natural gas company VNG signed an MoU with Sonatrach to examine the possibilities for green hydrogen projects. Algeria’s future as a hydrocarbons supplier could also extend beyond Europe as Chevron aims to reach a gas exploration agreement with Algeria and is assessing the country’s shale resources.

Complications & geopolitical dynamics

Translating all that interest and cooperation into more Algerian output, and stable secure supplies for Italy and Europe, on the other hand, is a different story. There are several factors that hamper or complicate the growth of the Algerian gas industry and the potential North-South Axis. Those complications can be divided into two broad groups: (i) industry specific complications and (ii) complex (international) politics.

Industry specific complications

There are specific limitations to the technical feasibility of increasing production. Years of underinvestment, due to corruption, unattractive fiscal terms and a slow bureaucracy, have resulted in less exploration and development of new fields, which roughly take 3-5 years from the exploration phase to production. In combination with decline from maturing fields, this limits industry growth and export potential in the short-term. Internal audits show that Sonatrach can barely mobilize an additional 4 bcm per year, let alone the additional 9 bcm meant for 2024. Doing so will take a bite out of its LNG business, which currently sells for a much higher price. Exploration and development will take time and mostly affect the medium-term in 3-5 years. Furthermore, Algeria has to perform a balancing act between its exports and increasing domestic demand, which is set to grow 50% by 2028.

A North-South axis will require Italy to upgrade its gas network as well. The country will have to establish several energy corridors to demand markets in Europe and expand its domestic gas network, which requires billions of investment. In this light, some analysts point to the fact that claims about such an axis are currently rhetoric and are meant to secure investments that are needed for its own gas industry.

Geopolitics

Geopolitical considerations also may influence gas flows toward Europe. For starters, Algeria has a complicated relationship with Morocco, which according to Algiers, 'occupies’ the Western Sahara. Algeria maintains it is a sovereign territory and in 2021, this row resulted in the suspension of the GME pipeline, which runs through Morocco. While Spanish imports through the Medgaz pipeline increased from 8 bcm to 9 bcm in 2022, the closure of the GME pipeline resulted in an overall decrease of exports to Spain by more than 35%. By using gas (revenues) as a tool of statecraft, Algeria also managed to convince Tunisia in countering Morocco, after handing it economic aid.

The country’s relations with Russia might also complicate gas flows. Its relation encompasses military cooperation, including joint military exercises and weapons purchases. Algeria is the 6th largest importer of weapons in the world and roughly 70% of Algeria’s weapons are sourced from Russia. In 2023, its largest budget draft ever included a rough 130% or $13.5 billion rise in military expenditure and, in November, plans were announced to dramatically increase its acquisition of Russian military equipment in 2023, including stealth aircraft, bombers and fighter jets, and new air defense systems.

With the war in Ukraine, Algeria’s relation with Russia creates a risk of sanctions, with some U.S. senators and EU parliamentarians being particularly vocal on this. As a result of sanction risk, Sonatrach included a clause in its gas contracts, which allows for currency denomination change every 6 months, reflecting warrines of U.S. sanctions and dollar-denominated gas trade. Its recent application to BRICS, will increase the country’s capacity to charter its own foreign policy, without endangering security and trade ties to Beijing and Moscow.

Outlook

Significant rises in Algerian export output, outside of its current commitments, are not likely in the short-term.

Ambitions with regards to a potential North-South axis are largely rhetorical and meant to increase investment and gather broader regional and European-wide support for an energy corridor.

Sanction-risks remain low. Because of Algerian significance to the European gas market, the EU and its member states will likely try to maintain good ties with the North-African country.

The effect of future massive weapons purchases from Russia will likely have a negative effect on relations with the EU, but it is unclear whether that will immediately impact (future) gas flows.

Increasing gas revenues and bigger budgets will decrease the risk of domestic instability. As a consequence, Algeria has the possibility to charter a more active foreign policy - something we are currently already seeing. The main goal of such a foreign policy will be to stabilize its immediate neighborhood.

Risks of the German gas plans

This comprehensive mini-report from the Global Commodities Watch identifies the risks involved with German preparations and plans to curtail Russian gas supplies.