A Strait Betwixt Two

As the Yemeni Houthi group's assault on maritime vessels continues to escalate, the risk to key commodity supply chains raises global concern. As analysed in this series' previous article (available here), conflict escalation impacts the region's security, impacting key trade routes and global trade patterns. The Suez Canal is a key trade route whose stability and security could impact and shift trade dynamics. As the search for alternative trade routes ensues, the Strait of Hormuz makes use of a power vacuum to expand its influence.

Suez Canal

The Suez Canal is a 193-kilometre waterway that connects the Red Sea to the Mediterranean Sea. Approximately 12% of global trade passes through the Canal, granting it vast economic, strategic, and geopolitical influence on a global scale. This canal shortens maritime trade routes between Asia and Europe by approximately 6,000 km by removing the need to export around the Cape of Good Hope and serves as a vital passage for oil shipments from the Persian Gulf to the West. Approximately 5.5 million barrels of oil a day pass through the Canal, making it a ‘competitor’ of the Strait of Hormuz.

Global trade via the Suez Canal is likely to decrease as a result of the rising tensions near the Bab el-Mandeb Strait. Due to their geographic predispositions, the Bab el-Mandeb Strait and the Suez Canal are interdependent; bottlenecks in either trade choke point will have a knock-on effect on the other. Bottlenecks caused by Houthi aggression against ships in the strait are likely to redirect maritime traffic from the Suez Canal to alternative passageways. From November to December 2023, the volume of shipping containers that passed through the Canal decreased from 500,000 to 200,000 per day, respectively, representing a reduction of 60%.

Suez Canal Trade Volume Differences (metric tonnes)

The overall trade volume in the Suez Canal has decreased drastically. Between October 7th, 2023, and February 25th, 2024, the channel’s trade volume decreased from 5,265,473 metric tonnes to 2,018,974 metric tonnes. As the weaponization of supply chains becomes part of regional economic power plays, there is a global interest in decreasing the vulnerability of vital choke points via trade route diversification. The lack of transport routes connecting Europe and Asia has hampered these interests, making choke points increasingly susceptible to exploitation.

Oil Trade Volumes in Millions of Barrels per Day in Vital Global Chokepoints

Source: Reuters

Quantitative Analysis

Many cargoes have been rerouted through the Cape of Good Hope to avoid the Red Sea region since the beginning of the Houthi conflict. Several European automakers announced reductions in operations due to delays in auto parts produced in Asia, demonstrating the high exposure of sectors dependent on imports from China.

In the first two weeks of 2024, cargo traffic decreased by 30% and tanker oil carriers by 19%. In contrast, transit around the Cape of Good Hope increased by 66% with cargoes and 65% by tankers in the same period. According to the analysis of JP Morgan economists, rerouting will increase transit times by 30% and reduce shipping capacities by 9%.

Depiction of Trade Route Diversion

Source: Al Jazeera

More fuel is used in the rerouted freight, an additional cost that increases the risk of cargo seizure and results in elevated shipping rates. The most affected routes were from Asia towards Europe, with 40% of their bilateral trade traversing the Red Sea. The freight rates of the north of Europe until the Far East, utilising the large ports of China and Singapore, have increased by 235% since mid-December; freights to the Mediterranean countries increased by 243%. Freights of products from China to the US spiked 140% two months into the conflict, from November 2023 to January 25, 2024. The OECD estimates that if the doubling of freight persists for a year, global inflation might rise to 0.4%.

The upward trend in freight rates can be seen in the graphic pictured below, depicting the “Shanghai Containerised Freight Index” (SCFI). The index represents the cost increase in times of crisis, such as at the beginning of the pandemic, when there were shipping and productive constraints, and more recently, with the Houthi rebel attacks. Most shipments through the Red Sea are container goods, accounting for 30% of the total global trade. Companies such as IKEA, Amazon, and Walmart use this route to deliver their Asian-made goods. As large corporations fear logistic and supply chain risk, more crucial trade volumes could be rerouted.

Shanghai Containerized Freight Index

Energy Commodity Impact

Of the commodities that traverse the Red Sea, oil and gas appear to be the most vulnerable. Before the attacks, 12% of the oil trade transited through the Red Sea, with a daily average of 8.2 million barrels. Most of this crude oil comes from the Middle East, destined for European markets, or from Russia, which sends 80% of its total oil exports to Chinese and Indian markets. The amount of oil from the Middle East remained robust in January. Saudi oil is being shipped from Muajjiz (already in the Red Sea) in order to avoid attack-hotspots in the strait of Bab al-Mandeb.

Iraq has been more cautious, contouring the Cape of Good Hope and increasing delays on its cargo. Iraq's oil imports to the region reached 500 thousand barrels per day (kbd) in February, 55% less than the previous year's daily average. Conversely, Iraq's oil imports increased in Asia, signalling a potential reshuffling of transport destinations. Trade with India reached a new high since April 2022 of 1.15 million barrels per day (mbd) in January 2024, a 26% increase from the daily average imports from Iraq's crude.

Brent Crude and WTI Crude Fluctuations

Source: Technopedia

Refined products were also impacted. Usually, 3.5 MBd were shipped via the Suez Canal in 2023, or around 14% of the total global flow. Nearly 15% of the global trade in Naphta passes through the Red Sea, amounting to 450 kbd. One of these cargoes was attacked, the Martin Luanda, laden with Russian naphtha, causing a 130 kbd reduction in January compared with the same month in 2023. Traffic to and from Europe is being diverted in light of the conflict. Jet fuel cargoes sent from India and the Middle East to Europe, amounting to 480 kbd, are avoiding the affected region, circling the Cape of Good Hope.

Due to these extra miles and higher speeds to counteract the delays, bunker fuel sales saw record highs in Singapore and the Middle East. The vessel must use more fuel, and bunker fuel demand increased by 12.1% in a year-over-year comparison in Singapore.

In 2023, eight percent, or 31.7 billion cubic metres (bcm), of the LNG trade traversed the Red Sea. The US and Qatar exports are the most prominent in the Red Sea. After sanctioning Russia's oil because of the Ukrainian War, Europe started to rely more on LNG shipments from the Middle East, mainly from Qatar. The country shipped 15 metric tonnes of LNG via the Red Sea to Europe, representing a share of 19% of the Qatari LNG exports. Vessels travelling to and from Qatar will have to circle the Cape of Good Hope, adding 10–11 days to travel times and negatively impacting cargo transit.

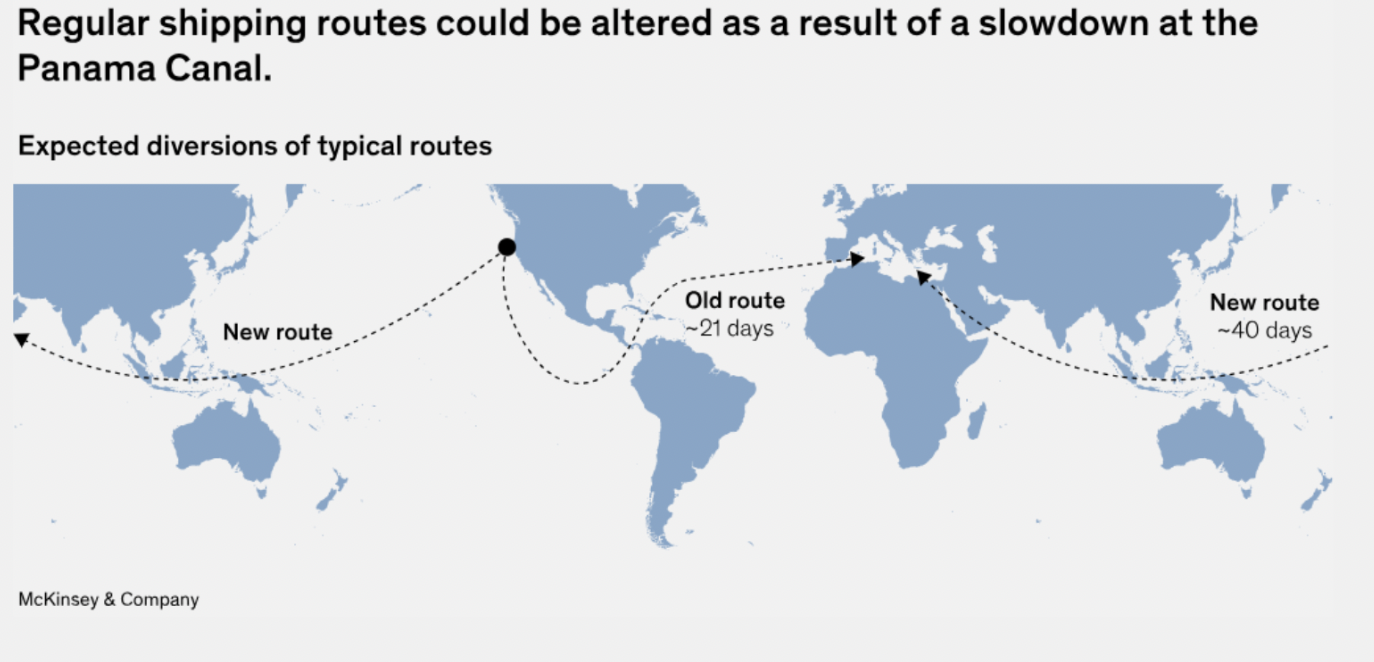

US LNG export capacity has increased in the past few years, sending shipments to Asia via the Red Sea. The Panama Canal receives many LNG cargoes from the US via the Pacific, yet its traffic limitations cause US cargo to be routed through the Atlantic and the Red Sea. The figure “Trade Shipping Routes” below displays the dimensions of the shifts that US LNG cargoes must take in the absence of passage via the Panama Canal.

Trade Shipping Routes

Source: McKinsey & Company

Until January 15, at least 30 LNG tankers were rerouted to pass through the Cape of Good Hope instead. Russia's LNG shipments to Asia are currently avoiding the Red Sea, and Qatar did not send any new shipments in the last fortnight of January after the Western strikes at Houthi targets.

Risk Assessment

A share of 12% of oil tankers, ships designed to carry oil, and 8% of liquified gas pass through this route towards the Mediterranean. Inventories in Europe are still high, but if the crisis persists for several months, energy prices could be aggravated. As evidenced by the sanctions against Russia, cargo reshuffling is possible. Qatar can send its cargoes to Asia, and those from the US can go to European markets, allowing suppliers to effectively avoid the Red Sea.

Around 12% of the seaborn grains traversed the Red Sea, representing monthly grain shipments of 7 megatonnes. The most considerable bulk are wheat and grain exports from the US, Europe, and the Black Sea. Around 4.5 million metric tonnes of grain shipments from December to February avoided the area, with a notable decrease of 40% in wheat exports. The attacks affected Robusta coffee cargoes as well. Cargoes from Vietnam, Indonesia, and India towards Europe were intercepted, impacting shipping prices and incentivizing trade with alternative nations.

Daily arrivals of bulk dry vessels, including iron ore and grain from Asia, were down by 45% on January 28, 2024, and container goods were down by 91%. However, further significant disruptions to agricultural exports are not expected. Most of the exports from the US, a large bulk, were passing through the Suez Canal to avoid the congestion of the Panama Canal due to the droughts that limited the capacity of circulation. These cargoes are now traversing the Cape route.

Around 320 million metric tonnes of bulk sail through Suez, or 7% of the world bulk trade. No significant impacts are predicted for iron ore or coal, which represented 42 and 99 megatonnes of volume, respectively, shipped through the Red Sea in 2023. Most of the dry bulks that traverse the impacted region can be purchased from other suppliers, precluding significant supply disruptions.

As of March 1st, reports show that only grain shipments and Iranian vessels were passing through the Red Sea. There were no oil or LNG shipments with non-Iranian links in the Red Sea. These developments illustrate the significant trade shifts caused by the Red Sea crisis. As of today, a looming threat lies in the Houthis’ promises of large-scale attacks during Ramadan. The lack of intelligence on the Houthi’s military capacity and power makes it difficult to ascertain the extent of future conflicts, generating further uncertainty in commercial trade.

The Strait of Hormuz

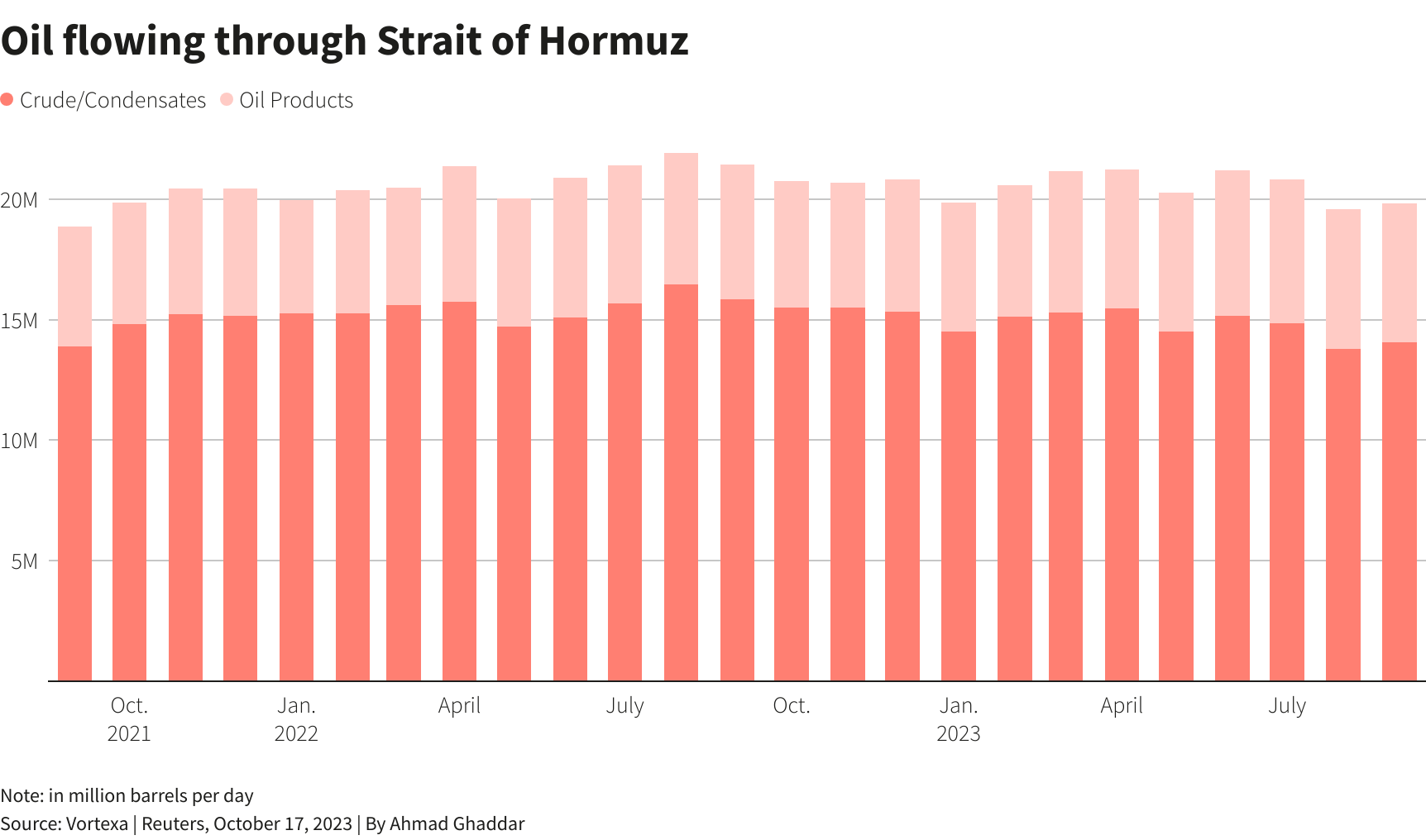

The Strait of Hormuz is a channel that connects the Persian Gulf to the Gulf of Oman, providing Iran, Oman, and the UAE with access to maritime traffic and trade. The strait is estimated to carry about one-fifth of the global oil at a daily trade volume of 20.5 million barrels, proving to be of vital strategic importance for Middle Eastern oil supply the world’s largest oil transit chokepoint. The strait is a prominent trade corridor for a myriad of oil-exporting nations, namely the OPEC members Saudi Arabia, Iran, the UAE, Kuwait, and Iraq. These nations export most of their crude oil via the passage, with total volumes reaching 21 mb of crude oil daily, or 21% of total petroleum liquid products. Additionally, Qatar, the largest global exporter of LNG, exports most of its LNG via the Strait.

Geographic Location of Strait of Hormuz

Source: Marketwatch

Although the strait is technically regulated by the 1982 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, Iran has not ratified the agreement. Through its geostrategic placement, Iran can trigger oil price responses through its influence on trade transit, establishing the country’s regional and global influence.

Strait of Hormuz Oil Volumes

Source: Reuters

Experts are particularly worried that the turbulence is likely to spread to the Strait of Hormuz now that Iran backs the Houthis in Yemen and might want to support their cause by doubling down regionally. However, this is something that would cause a lot of backlash in the form of a further tightening of economic sanctions against Tehran, which might deter further provocations.

Despite Iran’s previous threats to block the Strait entirely, these have never gone into effect. Diversifying trade routes to avoid supply shocks and bottlenecks is of interest to regional oil-exporters dependent on the route for maritime trade access. Such diversification attempts have already been undertaken, as seen by the UAE and Saudi Arabia's attempts to bypass the Strait of Hormuz through the construction of alternative oil pipelines. The loss of trade volume from these two producers, holding the world's second and fifth largest oil reserves, respectively, severely hindered the corridor’s prominence.

The attacks on the Red Sea might cause damage to the oil and LNG cargo from countries in the Persian Gulf, increasing costs for oil and gas exporters. However, cargoes could find alternative destinations. The vast Asian markets, which face a shortage of energy products due to a loss of trade through the Red Sea, could be a potential suitor. Finding new LPG (liquefied petroleum gas) contracts could be beneficial for Iran, and its recently enhanced production capacity could supply various markets.

Geopolitics and Prospects for a Route Shift

Although the Strait of Hormuz stands to capture diverted trade flows from the Suez Canal, its global influence is still limited by Iran’s geopolitical ties. As exemplified by the Iran-US conflict, Iran’s conflicts can severely impact traffic through the Strait, significantly impacting the stability of the route and prospects for future growth.

Although security and stability are of paramount importance to trade, efforts to provide these traits could be counterproductive. On March 12th, China and Russia conducted maritime drills and exercises in the Gulf of Oman with naval and aviation vessels. According to Russia's Ministry of Defence, this five-day exercise sought to enhance the security of maritime economic activities using maritime vessels with anti-ship missiles and advanced defence systems. Over 20 vessels were displayed in this joint naval drill, attempting to lure trade through the promise of stability and security.

Whether meant as a display of power or a promise of security, the pronounced presence of Russian and Chinese forces could aggravate geopolitical tensions and increase the potential for conflict in the region, driving global trade prospects down. With precedents of trade conflict, such as the IRGC’s seizure of an American oil cargo in the Persian Gulf on January 22nd, various countries might be sceptical of rerouting commodity trade through the Strait.

Tensions are also aggravated by Iran’s alleged assistance in the Houthi attacks. The US has supposedly communicated indirectly with Iran to urge them to intervene in the region. China and Russia’s interest in improving the Strait’s trade prospects would benefit from a de-escalation of the Houthi conflict, as shown by China’s insistence on Iran’s cooperation in the Houthi conflict. As the conflict stands, the Strait’s prospect as an alternative trade route is dependent not only on Iran’s reputation and presence in global conflicts but also on the route’s patrons and proponents.

Conclusion

The extent to which the Strait of Hormuz could benefit from trade diversion depends not only on its ability to pose itself as a viable trade route but also on the duration of the Houthi conflict. In order to capture trade volumes and increase international trade through the route, Iran would have to ameliorate its geopolitical ties and provide stability to compete with rising prospective trade route alternatives. Although the conflict in the Suez has yet to show promising signs of de-escalation, securing the Suez would likely cause previous trade volumes to resume and restore its hegemony in commodity trade. It remains to be seen whether the conflict will endure long enough to allow other trade routes to be established as alternatives and permanently shift power balances in global trade.

2024 Elections Report: Risks & Opportunities for Commodities Sector

In the ever-evolving landscape of global commodities, the year 2024 stands as a pivotal juncture marked by transformative elections across diverse regions. As nations prepare to cast their ballots, the outcomes hold the power to shape policies and strategies that will significantly influence energy, trade relations, and resource management worldwide.

This report encapsulates the intricate intersections between political shifts and their repercussions on the commodities sector. London Politica’s Global Commodities Watch has made a selection of the most significant countries, and analysed the potential impact of elections based on election programmes, past policies, and scenario planning.

Potential scenarios for Israel - Palestine conflict and effect on commodities

On October 7, Israel was attacked by Hamas. The event, which was classified as Israel’s 9/11 by Ian Bremmer, led to at least 1,300 fatalities and 210 abductions. Israel has launched a strong military response, and as of the 20th day since the original attack the situation remains unresolved. Both sides are experiencing ongoing hostilities and Netanyahu, Israel’s president, stated that the country is preparing for a ground invasion of the Gaza Strip, which will result in further civilian casualties.

Various groups are threatening to involve themselves in the conflict. Hezbollah, for instance, has issued warnings indicating the possibility of launching a significant military operation from Lebanon to northern Israel if the latter enters the Gaza Strip. It also has been discussing what a ‘real victory’ would look like with its alliance partners Hamas and Islamic Jihad. Israeli forces, on the other hand, bombed Syria shortly after air raids sounded in the Golan Heights, a disputed territory that has been annexed by Israel since 1967. This offensive targeted the Aleppo airport and sources claimed its goal was to stop potential Iranian attacks being launched from Syria. Additionally, Iran has faced accusations of funding the attack, which raises concerns about its involvement.

Consequences for commodities

The ongoing conflict has emerged as a significant geopolitical factor on global oil markets. However, there have not been immediate impacts on physical flows yet. During the weekend of 7th to 9th October there was an increase in Brent crude prices of about 4% , which later fell 0.2% after Hamas released two American hostages. Prices fell even further after Israel appeared to hold off on its widely expected ground invasion of Gaza. These dynamics show that the risk premium in the oil price takes into account the severity of the conflict and the likelihood for escalation.

Yet, Israel’s limited oil production capacity means that, if the conflict remains localised, it is unlikely to have a significant impact on global oil supply. Traditional energy commodities (and their prices), that can be viewed as a substitute to oil, have not been impacted so far either. Natural gas, for example, is both a substitute to oil and also largely produced by Israel with its southern offshore Tamar field. Despite European gas prices reaching their highest price since February on Friday 13th, markets do not appear to be pricing in the possibility of an escalation extending beyond Israel and Gaza. If that was the case, even higher prices would be recorded.

The most significant impacts on oil markets are more likely to occur if other nations actively engage in the conflict. After the explosion of a hospital in Gaza on 17th of October, Iran called for an oil embargo against Israel in retaliation for the deadly attacks. The Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries have expressed their unwillingness to support Iran, stating that “oil cannot be used as a weapon”, which helped markets to not consider any embargos for the moment. Moreover, the impact of this action would be limited, since Israel could source its oil from a wide array of other countries.

Another point worth mentioning, it is estimated that 98% of Israel’s imports and exports are made by sea, making the national ports a crucial part of the country’s infrastructure. These ports are currently under a significant risk of potential damage, which has heightened shipping insurance premiums and affected the costs of importing into and exporting from Israel.

Possible scenarios and implications

1. If the conflict remains confined to the Israel - Palestine region

While there could be short-term volatility in oil prices during the most intense attacks and as potential escalation threats rise, neither of these regions are significant oil producers. Therefore, recent rises are not expected to have a lasting impact on oil prices, which should soon stabilise between $93 and $100 per barrel. However, it is important to mention that this price range was already predicted before the current war between Israel and Palestine took place.

2. War involving Hezbollah

Some recent attacks have taken place between Israel and Hezbollah, however, if the latter joins the conflict, the impact on oil markets could be more substantial. This could lead to potential global economic consequences due to risk-off sentiment in the financial markets, leading to oil prices rising by $8 per barrel, approximately. Another group that can act on the conflict are the Houthis, an Iran-backed group in Yemen which allegedly launched missiles against Israel on October 19th, that were intercepted by the United States. While Yemen primarily exports cereal commodities, its involvement can further escalate geopolitical tension and instability in the region.

3. Iran enters the conflict formally

The most significant impact on the oil market would arise if Iran officially joins the conflict, potentially causing a $64 per barrel increase to a price of $152.38 for Brent crude. Iran controls the Strait of Hormuz, a passage crucial for connecting the Persian Gulf with the Indian Ocean. Thus, if the Strait is blocked, important countries for oil production such as Iraq, the United Arab Emirates, and Kuwait would be landlocked. Consequently, Iran would see its gas revenues rise due to higher prices. This situation also creates challenges for gas importing countries, especially for the EU’s energy security that has already seen a cut of supply from Russia.

As a consequence of Iran’s increased involvement shipping expenses would likely increase, also associated with war-risk premiums on shipping insurance. Those refer to additional costs that are also included in shipping prices to cover for vessels and cargo that are operating in areas of geopolitical risk. In the Ukrainian and Russian conflict for example, the war risk premium was firstly around 1% and has further escalated to 1.25%. While the overall value may not be significant, it can still present an additional challenge in the trading of energy related commodities.

Moreover, Iran is still exporting a significant amount through loopholes. If Iran decides to formally join the conflict, there probably would be stricter enforcement of sanctions by the United States which would tighten global oil supplies. Higher oil prices would also cause external geopolitical impacts. In the US, elevated oil prices could be a factor against the election of Joe Biden, who has invested significant political capital on the Middle East’s diplomacy with an attempt to normalise Saudi Arabia and Israel relations. For Russia, on the other hand, higher oil prices are vital to increase the country’s revenue and continue its war against Ukraine.

The most extreme scenario would entail Israel conducting a strike on Iran’s nuclear facilities, potentially causing oil prices to surge well beyond $150 per barrel. Therefore, heightened efforts to remove U.S. sanctions on Venezuelan oil would help relieve the strain on global oil prices. Increased access to Latin America's oil resources could act as a shock absorber against price increases and supply disruptions. In the US, more specifically, it would offer a more favourable outlook to Joe Biden's administration.

The King’s Gambit: The Opportunities and Risks of Israeli Approval of Gaza’s Offshore Gas Extraction

On 18 June 2023, Israel’s prime minister, Benjamin Netanyahu, announced that his country had given the green light to the Palestinian Authority’s (PA) development of a natural gas field off the coast of the Gaza Strip. Given the strained relations and recurring rounds of violent escalation between Israel and militants in Gaza, such a move is not straightforward and must be explained with reference to the political, economic and security interests of the parties involved.

Israel’s interests

To the outside observer, a concession to the Palestinians by an Israeli government broadly seen as the country’s most right-wing ever may be surprising. Yet it is an enduring fact that Israel’s most bold overtures to its neighbours have been carried out by the right wing. It was Menachem Begin’s Likud government that exchanged the Sinai Peninsula for a peace treaty with Egypt in 1979. Karine Elharrar, Israel’s Energy Minister under Israel’s previous, more centrist government related that she had been approached with the Gaza gas proposition toward the end of 2021 but ruled it out as unfeasible as her government was already under fire from the then-Netanyahu-led opposition for its pursuit of a maritime gas deal with Lebanon. The reason Israeli public opinion considers giveaways by the right more palatable is the impression that they have been vigorously negotiated over and, if made, must be squarely in the national interest. The logic here follows from the Israeli-Lebanese precedent: give your enemy something to lose, and they will think twice before risking all-out conflict.

The Israeli right has long opted for ‘managing’ the Israeli-Palestinian conflict over solving it. A recent, pressing challenge to this strategy has been the gradual disintegration of the PA, the governmental body created by the 1993 Oslo Accords and charged with governing the Palestinian Territories. It lost control of Gaza to Hamas after the latter’s violent takeover of the strip in 2007 and its legitimacy among the West Bank’s population has been undermined by accusations of corruption, mismanagement, and collaboration with Israel. Israel hopes the deal will shore up the PA, an important security partner in preventing and punishing local terrorist attacks, by bringing much-needed funds and restoring its image as a responsible, effective authority.

Nevertheless, Israeli leaders do not harbour any illusions about the fact that some of the revenue generated by the gas sales is bound to end up in the hands of Hamas, a militant group designated by it, the US, the EU, and many others as a terrorist organisation. This is widely seen as the reason for the stalling of the initiative since it was first proposed in 1999. Recently, however, experts have suggested that Israel intended the concession as a quid-pro-quo for Hamas’s acquiescence over its military campaign against the Palestinian Islamic Jihad (PIJ) in May 2023. Such an approach attempts to gain Hamas’s cooperation through a carrot-and-stick strategy.

Gaza’s interests

On Gaza’s side, the foremost imperative is economic. Years of economic blockade by Israel and Egypt, alongside local mismanagement have turned Gaza into what certain human rights organisations have called an ‘open-air prison’. Its 2.3 million inhabitants experience power cuts for up to 12 hours a day, a result of an over-dependence on a small local oil-fuelled power plant and insufficient Israeli electricity. Meanwhile, the Gaza Marine field is thought to hold almost 30 billion cubic metres (1 trillion cubic feet) of natural gas. If tapped, this source would be more than enough to cover the area’s estimated 500-megawatt daily requirement, with the remainder piped into liquefaction units in Egypt and sold on global markets, yielding billions of dollars in revenues.

If such a plan materialises, both the PA and Hamas will seek to claim credit. The PA will attempt to win back its support in Gaza and the West Bank as a government that secured economic development and raised living standards through internationally negotiated agreements. Hamas, for its part, would build on its credentials not only as a force of resistance to Israel but as a provider of economic and social benefits in the strip, potentially facilitating its formal consolidation in the West Bank too.

Risks

Progress on an Egyptian-mediated agreement on gas by Israel and the PA faces three principal risks.

First, and most obviously, the breakout of a new round of violence between Israel and Hamas, possibly, but not necessarily, as part of a broader regional escalation (e.g. involving clashes across the Israeli-Lebanese border) will likely cause Israel to take the deal off the table. Israel’s leadership must convince itself, and its supporters, that it is not arming its enemies.

Second, Israel is counting on Egypt to act as a guarantor and third-party stakeholder in securing Hamas’ continued cooperation and underwriting its good behaviour. Yet while Egypt has proved an indispensable mediator in this regard over the last decade, it is unclear how much sway it holds over the militant organisation in comparison to Iran, its chief ally and financial backer. Given the Israeli-Iranian geopolitical archrivalry, it is not straightforward to assume that Hamas is either willing or able to peacefully coexist with Israel for long.

Third, and finally, the recent political turmoil in Israel as a result of the judicial reforms introduced by Netanyahu’s coalition might complicate his efforts to justify the move to his supporters. If the coalition eventually backs down from the reforms demanded by its hard-line elements and supporter base, the addition of a formal concession to the Palestinians may become even harder to stomach, especially after Netanyahu himself had opposed Israel’s previous deal with Lebanon as a ‘surrender to terror’.

The next step

Full-scale extraction of natural gas from the Gaza Marine field will require the PA to obtain a final agreement designating the status of the field in which Israel will relinquish any remaining claims to the reservoir. Israel’s apparent green light for the project could bolster the economic prospects for the strip, and may succeed in furthering regional stability, as its proponents hope. If successful, the project and its Israeli-Lebanese predecessor of last year may illustrate the opportunities for opposing states of leveraging the relative ambiguity and lesser politicisation of maritime boundaries to reach compromises in spite of intransigent public audiences. Nevertheless, the multiplicity of actors involved, with their limited power and often conflicting interests, means the project is fraught with risks that threaten to turn it into another false start in a troubled political relationship.

Image credit: Bureau of Safety and Environmental Enforcement (BSSE)

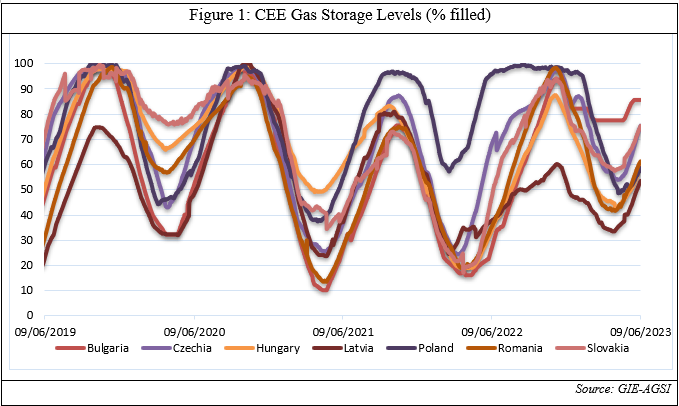

Central and Eastern European countries are well-prepared for the next 2023/2024 heating season, but risks still loom large

Central and Eastern European (CEE) countries are well-prepared for the next 2023/2024 heating season, despite the presence of moderate risks. This is due to two factors. Their strategies to diversify from Russian gas have been overall successful, and current gas storage levels are high. As of June 2023, they are considerably higher than in the same period last year. While at the beginning of June 2023 they amounted to an average of 49%, nowadays storage facilities are filled between 53.5% (Latvia) and 85.6% (Bulgaria). What emerges is a positive situation with regard to the CEE’s energy security in winter 2023/2024. Indeed, according to the EU Gas Storage Regulation (EU/2022/1032), to ensure reasonable gas prices in the next heating season, EU countries have to reach a storage level of 90% before October 2023. Considering that all CEE states have achieved the intermediate targets for May set out in the regulation and that they still have the entire summer to build up their gas storage facilities, they will likely reach the EU-mandated level of 90% before next winter.

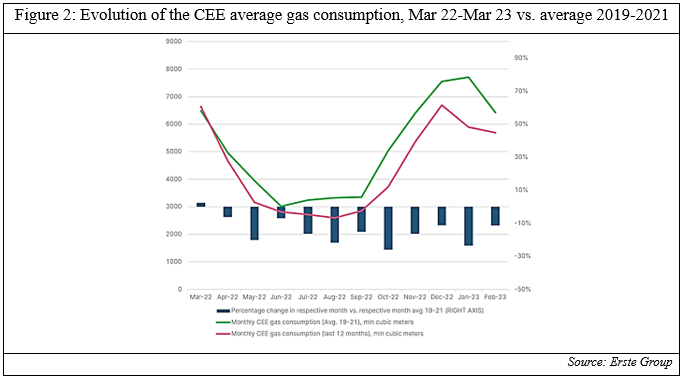

Moreover, the CEE states have also reduced their vulnerability to Russian gas by reducing their total demand for natural gas and diversifying their suppliers. When looking at the gas consumption in the region over the last 12 months as opposed to the average between 2019 and 2021, it can be noted that it decreased by 14% -more than the Eu average reduction of 11%- with a more visible decline taking place since mid-2022 [Figure below]. At the same time, they also diversified the remaining gas imports away from Russia, importing natural gas from Scandinavian countries (especially Norway) and LNG from overseas, including the US. In this regard, CEE countries were supported by the construction, ahead of the 2022/2023 heating season of several gas interconnectors, i.e., physical infrastructure systems that enabled natural gas transportation from other European countries. All these factors allowed the CEE to reduce its dependence on Russia.

In 2022, the IMF estimated that a potential Russian gas supply shut-off would have led to a GDP output loss of an average of 2.8%, compared to an EU average of 2.3%. In the short term, Hungary, the Slovak Republic and Czechia -which were the most vulnerable CEE countries- were expected to experience gas consumption shortages of up to 40% and a potential GDP decline of up to 6%. However, even if later in 2022 Russia did halt its gas supplies to the CEE, the expected gas shortages did not materialise. And while the CEE annual growth rate will slow down to an average of +0.6% in 2023 according to the European Commission, this is still double the expected EU average 2023 growth, and the output losses were considerably less than what was projected a year earlier by the IMF. In other words, countries in the region have so far proved to be economically resilient.

Nevertheless, the CEE still faces challenges regarding its energy security. Mainly, this relates to the steep surge in energy prices in the region following Russia’s weaponisation of gas supplies to the EU. After Gazprom unilaterally changed the terms of its gas supply contracts demanding payments in rubles, it halted all supplies to Poland and Bulgaria, which refused to pay according to the new rules. Even if Slovakia, Czechia and Hungary agreed to pay in rubles, Russian gas flows were anyway gradually stopped. First, Russian supplies through the Yamal pipeline ceased in May 2022, then, gas in transit through Ukraine also significantly decreased. Lastly, in August 2022 Moscow completely stopped the Nord Stream 1 pipeline. To date, the main way Russian gas flows to Europe is via the TurkStream route (which however supplies only Hungary and Serbia). The other is the Ukraine route, but this is likely to reduce in the coming months. As a result, energy prices in the region rose substantially, affecting especially energy-intensive industries. In 2022, producer energy prices increased by 93%. Coupled with the increase in inflation and the decision by CEE central banks to raise their policy interest rates, the increase in energy prices led to a surge in the production costs of CEE industries. As the CEO of Volkswagen Thomas Schafer claimed “Europe is not cost-competitive in many areas, in particular, when it comes to the costs of electricity and gas”. As a result, CEE energy-intensive manufacturing firms cut energy consumption and jobs, while substituting their own production with cheaper energy-intensive imports. Even if currently energy prices have decreased, there is the possibility that they will rise again next winter, when energy demand will rise again.

The overall situation of the CEE with regard to its energy security is positive, since storage facilities in the region have reached an adequate level, and the CEE has reduced its dependence on Russia. However, CEE countries have to ensure energy price stability for their industrial sector. This is especially important in view of the upcoming winter, when energy demand will rise again. In order to avoid such a scenario, CEE countries have to increase their diversification efforts to expand the number of reliable gas suppliers. This will not be an easy task, especially for landlocked states in the region such as Hungary and Slovakia.

Pipeline sabotage? Nord Stream and the politicisation of critical infrastructure

On September 26 and 27, gas leaks and explosions were reported on the Nord stream 1 and 2 pipelines. These occurred in Baltic Sea international waters, near the Danish island of Bornholm. Although neither of the pipelines was active at the moment, the amount of gas leakage was still significant. The timing, significance, and location of the leaks has led some to speculate that it was sabotage and that Russia deliberately attacked the pipelines.

So far, however, Western governments and officials have refrained from pointing fingers directly to Russia. As NATO secretary general Jens Stoltenberg argued: “This is something that is extremely important to get all the facts on the table, and therefore this is something we’ll look closely into in the coming hours and days”. It has however highlighted the importance of critical infrastructure and its role in the current stand-off between the West and Russia.

So what consequences did the leakage and supposed ‘sabotage’ have?

Economic consequences

The damage to Nord Stream coincided with news that new arbitrations over payments might lead to Russian sanctions against Naftogaz, Ukraine’s largest oil and gas companies. Consequently, benchmark futures of natural gas jumped 22%, the highest increase in over three weeks. Markets seem to have taken into consideration that now that pipelines have been damaged, the EU can’t request for them to be opened in case of an emergency. Nevertheless, with storage sites nearly at full capacity, heightened LNG imports, and mild weather forecasts for October, markets remained relatively calm.

Environmental

The environmental impact has been significant. Gazprom estimated that 0.8 bcm was released at the leaks. That number is almost equal to 1% of annual UK natural gas consumption, or 3% of its annual emissions. Were both pipelines actually active, the impact could have been much worse.

Political

After Danish and Swedish authorities launched investigations, suspicions of sabotage strengthened. In a statement by the Swedish security police, they said there were “detonations”. And in a joint letter to the UNSC, they stated that leaks were probably caused by an “explosive load of several hundred kilos”. President Biden argued the leaks were a deliberate act of sabotage as well. Meanwhile, Russian president Putin claimed the US and its allies were behind the attack.

The main logic behind a potential sabotage from the Russian side would be intimidation. Both in the Baltic Sea and the Atlantic, lots of critical infrastructure, such as pipelines or IT-cables, lie on the seabed. The attack on Nord Stream therefore would be a showcase for what Russia could do to other critical infrastructure. Ultimately, however, it would also mean that Russia has lost its element of leverage with gas.

As a consequence, EU energy ministers discussed the issue and European countries stepped up military patrols. In the North Sea, Germany, the UK, and France helped Norway in a show of force to increase security and patrol near energy sites. This was also a consequence of several unidentified drones being spotted near the sites. In the Mediterranean, Italy increased patrols near its pipelines which connect North Africa to Europe.

Risks

If this event turns out to be Russian sabotage, it adds a dimension to the conflict between the West and Russia. Although that conflict consisted of economic warfare and aspects of hybrid-warfare, physical attacks (on critical infrastructure) were absent. It begs the question whether we have entered a new phase of the war.

The risk, however, of physical attacks on other critical infrastructure remains limited. It is important to highlight that no gas flows were disrupted, because of Nord Stream’s inactivity. Combined with the ambiguity that was left about the perpetrator of the attacks, damage could be done without any consequences. This grey-zone aggression has been part of Russia’s playbook for years. Nevertheless, Russia knows the significance of physical attacks on other active pipelines would be far greater, and are more likely to trigger an article 4 or 5 response from NATO, even where proof is hard to ascertain. This limits the risk of physical attacks on other critical infrastructure.

The risks of 1) cyber attacks on critical infrastructure and 2) physical attacks on pipelines running through Ukraine, on the other hand, are greater, because it is more likely that Russia can maintain ambiguity there. It demonstrates the vulnerability of critical infrastructure and the difficulty of responding to coordinated attacks.