Climate Policies for the Shipping Industry: What They Mean for Global Supply Chains

Just as businesses throughout the world grapple with the effects of the coronavirus pandemic and the Ukraine crisis on global supply chains, another issue looms: new emissions standards that promise to affect how shippers run numerous transoceanic and regional channels.

Decarbonization is a costly endeavour, but the European Union (EU) seems willing to make the sacrifice. The European Commission offered a variety of options in July 2021 to help the EU accomplish its objective of decreasing greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions by 55% by 2030 compared to 1990 levels.

One such policy would eliminate free allowances for cement, iron, steel, fertiliser, and aluminum producers and instead assess import duties on these items based on their carbon footprint. This so-called carbon border adjustment mechanism (CBAM) attempts to even out the playing field by requiring other nations around the world exporting to the EU to account for the carbon they generate whilst exporting steel. CBAM is typically imposed and regulated by the recipient country, which imposes a carbon tax on some imported commodities at a rate equivalent to that of comparable local products.

To add to the difficulties, the EU intends to include ships in its Emissions Trading System (ETS) in 2023. For journeys between EU and non-EU ports, shipping corporations will be required to purchase licenses for 50% of emissions. Danish shipping giant Maersk has already declared tariffs for its trade lanes from Asia to North Europe and North Europe to the United States, and others will be required to jump on board. While an impending economic downturn is already bringing down shipping rates, they are unlikely to revert to pre-pandemic values in the long run because the additional expenditures must be paid for.

For managers planning their supply chains, there are several important things to pay attention to:

The costs of carbon reduction in maritime transport will alter the economics of where commodities are sourced. Although spot market rates have lately decreased, it is certainly impossible to expect cost to return to pre-pandemic levels. While carriers want to add significant new capacities in the coming years, forecasting shipping prices is difficult since the retirement of ageing capacity that will have difficulty following the ETS standards would likely balance out the increases. Much will depend on whether import demand in the United States falls and carriers choose to idle ships. Other industries, such as bulk carriers and vessels for transporting motor vehicles, may face substantial hurdles due to a lack of a robust order book for newer, more efficient vessels to supplant older ones that must be retired. High-volume trade corridors where container lines could employ newer, larger, and more efficient infrastructure will perform better, but overall, even if manufacturing costs are lower, it could make less sense to produce hundreds of products far away from where they will be consumed.

Lower-volume trade corridors will probably see fewer and more expensive services. This was anticipated in 2021, at the peak of the supply chain crises, when Japan lost certain direct eastbound connections to North America as container lines attempted to juggle capacity constraints and delays by eliminating port visits from their scheduled rotations (a more efficient technique of running the ships). The ETS rules will favour efficiency by allowing for larger ships, fewer port visits, and less frequent service while maximising capacity utilisation per ship.

Companies that export to Europe or have European suppliers should budget for the greater expenses that CBAM, ETS, and other countries' initiatives will impose. Managers must expect other nations outside the EU to adopt similar steps. Managers in the United States, for example, must pay heed to Canada, which has mandated a significant increase in carbon pricing for 2030. Comparable border adjustment methods may come under pressure in heavy-GHG-emitting industries like the steel industry.

As explained above, carbon transition policies and laws are expected to have a significant impact on the structure of supply chains. Cost increases and the practicalities of shipping logistics are both on the rise. Therefore, now is the time to start planning for this new age.

Image credit: Eric Kilby via Flickr

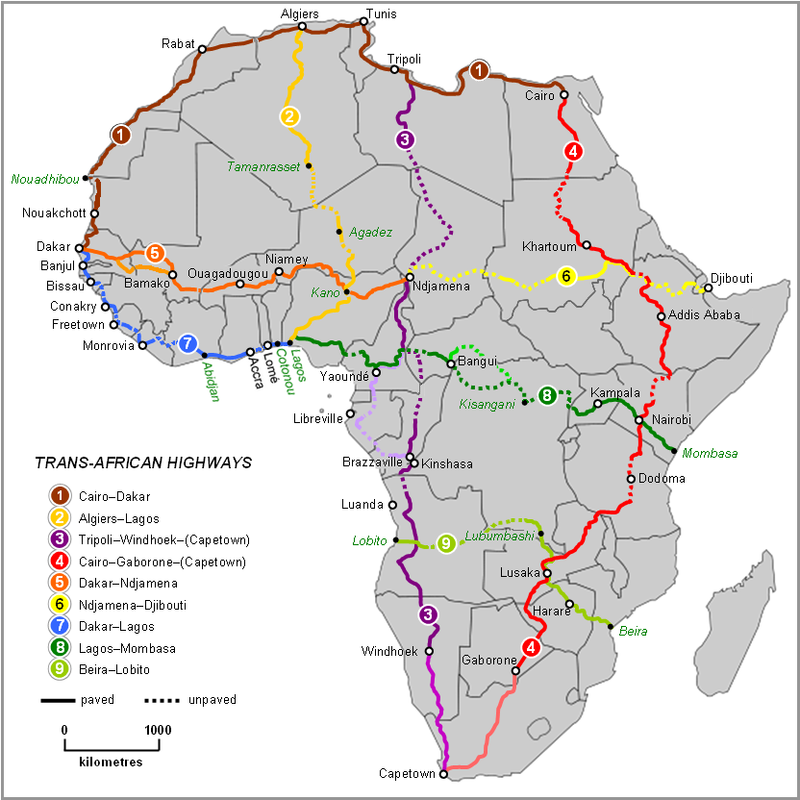

All roads lead to Africa: Opportunities and risks of the Trans African Highway network

In the build up to Nigeria’s next presidential elections due on 25 February 2023, the ruling All Progressives Congress (APC) party has suggested a suspension of spending limits in the budgetary process in its manifesto. According to presidential candidate Bola Tinubu, this would allow the government to “hire millions of unemployed Nigerians to modernise national infrastructure”, arguing that “a truly national highway system must be built to make road transportation faster, cheaper, and safer”. In the past, Minister for Public Works and Housing Babatunde Fashola has highlighted that these efforts transcend Nigeria’s borders, notably with the completion of the Trans–West African Coastal Highway (TAH 7): “We’re trying to deliver a better life for five countries and over 40 million people who use that corridor, almost on a daily basis. [...] The future is bright, this is an important investment for the people of Africa to achieve the objective of the Africa Union (AU) to create a trans-African highway.’’

Source: The Trans African Highway network, Wikimedia Commons, 2007.

The opportunities

This reinvigorated optimism for transnational transportation across the continent is embodied in the Trans African Highway (TAH) network, developed by the United Nations Economic Commission for Africa (UNECA), the African Development Bank (ADB), and the AU in conjunction with regional organisations. Financing is also supported by foreign development funds. The pursuit of such projects is vital to the development of African countries. In fact, the IMF estimates that around 40 per cent of the continent’s population lives in a landlocked country. Yet considering the high economic dependence of most African states on commodity exports and the low levels of intracontinental trade ー extra-African merchandise exports represented 86.6 per cent of total exports in goods from Africa in 2019 ー access to global shipping routes is vital. The completion of the TAH network coincides with the gradual setting up of the African Continental Free Trade Agreement (AfCFTA) which seeks to create a free trade zone encompassing all African Union states (bar Erythrea) and lift 30 million people out of extreme poverty by increasing intercontinental trade. UNECA highlights that the operationalisation of the AfCFTA will stimulate demand for land transportation and “double road freight from 201 to 403 million tonnes”.

The risks

Besides these potential opportunities, the gargantuan TAH network presents several economic, political, environmental, social and security risks. Economically speaking, the main risk source is the difficulty for developing countries to cover the high costs of maintenance. According to the World Bank, lack of maintenance can have aggravating socio-economic consequences: “poorly maintained roads constrain mobility, significantly raise vehicle operating costs, increase accident rates and their associated human and property costs, and aggravate isolation, poverty, poor health, and illiteracy in rural communities”. Furthermore, the South African National Road Agency estimates that “repair costs rise to six times maintenance costs after three years of neglect and to 18 times after five years of neglect”.

Politically speaking, an important risk source to the success of TAHs is the potential lack of cooperation of neighbouring states. Diplomatic leverage may be found in increasing bureaucratic processes at border crossings to cause congestion and delays ー although this risk may decrease in the long term as the AfCFTA is gradually implemented and imposes lighter border controls.

Environmentally and socially speaking, risk sources mostly emanate from rural areas. TAH projects may have to provide environmental mitigation and compensation for any ecological damage caused during construction phases, as well as go through long and complex acquisition processes due to tribal land ownership rules.

Finally, from a security perspective, the risk of land route disruptions and damage to infrastructure is extremely high in regions where conflict may arise, as is the case for the Ethiopian portion of TAH 4 which runs past the country’s war-torn northern regions.

Overall, the TAH network will undoubtedly help with African development through intracontinental trade. Yet, making this development sustainable for the decades to come will be a challenging feat Africans are already fully aware of: in the AfCFTA Secretariat's own words, “economic integration is not an event. It’s a process”.