Power and Protection - Smart Electricity Grids at the Crossroads of Technology and Geopolitics

In an age of evolving energy demands, climate concerns, and geopolitical tensions, the modernisation of power grids offers transformative potential. This report, authored collaboratively by the Global Commodities Desk and the Emergent Technologies Desk, provides actionable insights into the opportunities and challenges of smart grids, highlighting their pivotal role in building a sustainable, secure, and interconnected energy future. The geopolitical and economic dimensions of energy policy underscore the dual role of electrical and cyber systems, calling for robust protective measures against emerging threats. Discover how cutting-edge technologies and strategic policies are driving the energy revolution—read the full report to learn how smart grids are reshaping power systems and redefining energy security worldwide.

Small Modular Reactors Nuclear Renaissance?

In the era of climate urgency, increasing energy demands, and geopolitical uncertainties, Small Modular Reactors (SMRs) could redefine the energy landscape and provide viable alternatives to current energy sources. SMRs present a scalable, safer alternative to traditional nuclear power. This report from London Politica explores the potential of SMRs to revolutionise energy production, mitigate climate change, and enhance energy security. With uranium prices soaring and global interest in nuclear energy surging, SMRs are poised to play a critical role in the nuclear renaissance.

Our comprehensive analysis covers key regions, including the US, Europe, and China, examining their nuclear strategies, regulatory landscapes, and market dynamics. We also delve into the controversies surrounding uranium supply chains and the broader political and economic implications of nuclear power. Dive into our in-depth analysis of the future of SMRs and their global impact.

Eastern Entente: Houthi Campaign

Following developments in the Houthi campaign, the growing cooperation between China, Russia, and Iran is becoming a major concern for the Red Sea region. This emerging ‘Axis’ increases uncertainty for stakeholders in commodity trade, as the stability of the Suez Canal, Strait of Hormuz, and Gulf of Oman are threatened. Iran’s power projection in the region, characterised by the use of proxy groups in an ‘Axis’ of resistance, has paralysed global trade flows. Although China and Russia's involvement is presented as a means to stabilise the region and foster trade, rising scepticism clouds maritime traffic and worsen future prospects (as quantitatively analysed in a recent article by the Global Commodities Watch). The geopolitical and economic implications are profound and pose risks to all parties involved, raising questions about the motives behind this new ‘Axis’ formation and what it means for the disruptive ‘Axis of Resistance’.

Axis of Resistance - In Retrospect

Since the Iranian Revolution of 1979, the Tehran regime’s foreign policy has been characterised by its desire to propagate its brand of Shi’a Islam across the Middle East. To this end, it has long developed and fostered relationships with sympathetic proxy groups throughout the region. This has allowed it to project power in locations that might otherwise be beyond its reach while exercising some degree of “plausible deniability." In January 2022, this prompted the former Israeli Prime Minister, Naftali Bennett, to brand Iran “an octopus” of terror whose tentacles spread across the Middle East.

The country’s so-called “Axis of Resistance'' has expanded since 1979, its first major franchise being Hezbollah, which was founded in 1982 to counter Israel’s invasion of Lebanon that year. Its most recent recruit has been the Houthis. This group was established in northern Yemen in the 1980s to defend the rights of the country’s Shi’a Zaidi minority. What was initially a politico-religious organisation then evolved into an armed group that fought the government for greater freedoms. It was able to exploit the chaos of the Arab Spring to capture the national capital, Sana’a, in the autumn of 2014, and the group now controls around 80% of Yemen’s population.

Exactly when the Houthis became a part of the “Axis of Resistance” is something of a moot point, but the general consensus among the group’s observers is that it started receiving Iranian military assistance around 2009, with this almost certainly contributing to its capture of the Yemeni capital, Sana’a, in 2014. Since the HAMAS attack against Israel on October 7, 2023, it has rapidly emerged as a key Iranian franchise whose focus has been attacking shipping in the southern Red Sea. At the time of writing, an excess of 40 vessels had been targeted, while repeated US-led strikes against Houthi military infrastructure on the Yemeni coast appeared to have had limited success in degrading the group’s intent or capability.

March 2024 saw a proliferation in the number and efficacy of attacks, with the first three fatalities reported on the sixth of the month as the Barbados-flagged bulk carrier True Confidence was struck near the coast of Yemen. Around three weeks later, on March 26th, four ships were attacked with six drones or missiles in a single 72-hour period. Separately, on March 17th, what is believed to have been a Houthi cruise missile breached southern Israel’s air defences, coming down somewhere north of Eilat, albeit harmlessly.

Since starting their campaign against mainly international commercial shipping in the waters of the Red Sea and Gulf of Aden in November 2023, the Houthis have become one of the mostaggressive Iranian proxy groups in the Middle East. This and their apparently strengthened resolve in the face of US and UK strikes have substantially raised their profile internationally and won them plentifulplauditsfrom their supporters across the region. The perception that they are standing up to the US, Israel, and their Western cohorts has been instrumental in developing their motto“God is great, death to the U.S., death to Israel, curse the Jews, and victory for Islam” into a mission statement.

Map of Houthi Attacks

Source: BBC

Iran-Houthi Mutualism

In terms of regional geopolitics, the mutual benefits to Iran and the Houthis of their cooperation are far-reaching. For their part, the Iranians can use the Houthis to project power west into the Red Sea and Gulf of Aden, pushing back against the influence of Saudi Arabia and other Sunni states. Although not part of the Abrahamic Accords of 2020, Riyadh has been showing signs of a willingness to harmonise diplomatic relations with Israel, even since the events following October 7, 2023. This is a complete anathema to Tehran, for which the Palestinian cause is central to its historic antagonism with Tel Aviv. The fact that Saudi Arabia was instrumental in setting up the coalition of nine countries that intervened against the Houthis in Yemen from 2015 onwards only strengthens Tehran’s desire to confront the country’s influence regionally.

A secondary benefit of the Houthis’ Red Sea campaign is that it helps to maintain Tehran’s maritime supply lines to some of its franchise groups further north in Lebanon, Gaza, and Syria. Their importance to Iran’s proxy operations was illustrated in March 2014 when the Israel Defence Forces (IDF) conducted “Operation Discovery," intercepting a cargo ship bound for Port Sudan on the Red Sea’s western shores carrying a large number of M-302 long-range rockets. Originating in Syria, they were reckoned to have been destined for HAMAS in Gaza following a circuitous route that included Iran and Iraq and which would have culminated in a land journey from Port Sudan north through Egypt to the Levant.

Iran began to increase its military presence in the Red Sea in February 2011 and has since established a near-permanent presence there and in the Gulf of Aden, to the south, with both surface vessels and submarines. However, this footprint is relatively weak compared to that of its presence in the Persian Gulf, to the east, and it would be no match for the Western vessels that have been operating against the Houthis in the Red Sea since late 2023. The latter’s campaign in these waters can, therefore, only reinforce Iran’s presence thereabouts.

A lesser-known reason for Iran’s desire to maintain influence around the Red Sea is a small archipelago of four islands strategically located on the eastern approaches to the Gulf of Aden from the Indian Ocean and Arabian Sea. The largest of the four islands is called Socotra and is considered by some to have been the location of the Garden of Eden. With a surface area of a little over 1,400 square miles, it has, in recent years, found itself more and more embroiled in the struggle for hegemony between Iran and its Sunni opponents in the region. In this sense, it and its neighbours could be seen to have an equivalence to some of the small islands and atolls of the South China Sea that are now finding themselves increasingly on the frontlines of Beijing’s regional expansionism.

While officially Yemeni, Socotra has long enjoyed close ties with the United Arab Emirates (UAE), with approximately 30% of the island’s population residing in the latter. Following a series of very damaging extreme weather events in 2015 and 2018, the UAE strengthened its hold on Socotra by providing much-needed aid, with military units arriving entirely unannounced in April 2018. Vocal opposition from the Saudi-allied Yemeni government led to Riyadh deploying its own forces to the island in the same year, but these were forced to withdraw in 2020 when the UAE-allied Southern Transition Council (STC) took full control of the island. Since then, Socotra has been considered to be a de facto UAE protectorate, extending the latter’s own influence south into the Gulf of Aden.

Shortly after came the signing of the Abrahamic Accords, which normalised relations between Israel and several other regional countries, including the UAE. Enhanced cooperation with the UAE gave Tel Aviv a unique opportunity to expand its own influence in the region through military cooperation with its new ally. In the summer of 2022, it was reported that some inhabitants of the small island of Abd al-Kuri, 130 km west of Socotra, had been forced from their homes to make way for what has been described as a joint UAE-Israeli “spy base." For Iran, this means that Israel now has a presence at a strategic point on the strategically vital approaches to the Red Sea from the Indian Ocean.

Perhaps a greater irritant for both the Houthis and Iran is the presence of UAE forces on the small island of Perim. This sits just 3 km from the Yemeni coast in the eastern portion of the Bab al-Mandab Strait, giving it obvious strategic importance. The UAE took the island from Houthi forces in 2015 and started to construct an airbase there almost immediately. Although there is no known Israeli presence there, Perim is now a major thorn in the side of Iran’s own regional ambitions. In the regional tussle for supremacy, this is yet another very pragmatic reason for the Houthi-Iran relationship.

Perim Airbase

Source: The Guardian

Since February 2022, much has been made of the extent to which Ukraine has become a weapons incubator for both sides in the conflict there, not least with regard to innovative drone and AI technology. Given the range of weaponry now apparently at the disposal of the Houthis in the Red Sea and Gulf of Aden, it may be that that campaign is serving a similar purpose for a Tehran keen to test recent additions to its armoury. Indeed, the Houthis’ use of a range of modern weapons, including drones, Unmanned Underwater Vehicles, and cruise missiles, since November 2023 continues to be reported on a regular basis.

In return for prosecuting its campaign in the Red Sea, the latter received substantial material military support from Tehran, allowing them to raise their standing even more. The aforementioned attack, which killed three seafarers aboard the True Confidence, was the first effective strike against a ship using an Anti-Ship ballistic Missile (ASBM) in the history of naval warfare. First and foremost, this will have been regarded as a major coup for the Iranian military assets mentoring the Houthis in Yemen. Additionally, it has given the latter’s global standing a further boost since an attack of this magnitude would be more normally associated with the much more sophisticated standing military of a larger country.

A simplistic analysis of the Houthi-Iranian relationship could stop at this point. However, recent events in the Middle East and further afield show that it is a relatively small coupling in a much larger, global marriage of convenience. A clue to this appeared in media reporting in late January 2024, when The Voice of America reported that Korean Hangul characters had been found on the remains of at least one missile fired by the Houthis. This led to the conclusion that the Yemeni group has received North Korean equipment via Iran.

North Korean missile supposedly used by the Houthis

Source: VOA

Russian Involvement

In late March 2024, Russia and China signed a historic pact with the Houthi in which the nations obtained assurance of safe passage through the Red Sea and Gulf of Aden in return for ‘political support’ to the Shia militant group. Despite the assurance, safety for Russian and Chinese vessels is not guaranteed. In late January, explosions from missiles were recorded just one nautical mile from a Russian vessel shipping oil, while on the 23rd of April, four missiles were launched in the proximity of the Chinese-owned oil tanker Huang Lu. Evidently, increased regional tensions incur an extra security risk for Russian tankers, regardless of the will of the Houthis to keep said tankers safe.

The Kremlin is trying to walk a thin line between provoking and destabilising the West while simultaneously trying to avoid, literally and figuratively, capsizing regional Russian maritime activity. Its seemingly contradictory two-pronged approach aims to secure vital shipping routes while fostering an anti-Western bond with regional actors. Russia is seen upholding its anti-West rhetoric, which serves as a cornerstone for bonding with regional actors and pushing forth Russian economic interests, while silently attempting to facilitate regional de-escalation led by Washington. Despite being a heavy user of their veto power in the UNSC, Russia abstained from voting on Resolution 2722, which demands the Houthis immediately stop attacks on merchant and commercial vessels in the Red Sea.

On January 11th, Washington put forth UN Resolution 2722 to the UNSC, which sought to justify attacks on Houthi infrastructure as a push-back for the group’s recent activities in the Red Sea. During the voting procedure of the resolution, Russia chose to abstain, even though Moscow often frequents vetoes as a tactic to show support for Kremlin-friendly states in Africa and the Middle East. The resolution subsequently passed, and the US and UK commenced their first strikes on Yemen the following day. These reveal Russia’s interests in securing enough stability to continue shipping its estimated 3 million barrels of oil a day to India, while aligning with overarching geopolitical alignments.

Russia’s interest in stabilising regional conflicts may lie in the threats to its weapon supply chains. As the war in Ukraine drags on, Tehran’s importance as a weapon supplier increases the Kremlin’s collaboration efforts. Putin continues to foster and protect regional connections by actively protesting Western regional presence, attempting to balance the current crisis with crucial ties to middle-eastern nations.

Trade Route Diversion

Since the onset of the crisis in the strait, Russia has utilised the opportunity to bolster anti-Western and pro-Russian sentiments. For one, Russia has flagged various Russian transport initiatives. On January 29th, Russia’s Deputy Prime Minister, Alexey Overchuk, noted that Russia’s “main focus is on the development of the North-South international transportation corridor," which is a 7200-km multi-modal transport network offering an alternative and shorter trade route between Northern Europe and South Asia.

International North-South Trade Corridor

A key part of the trade route involves an imagined rail network spanning from Russia to Iran. Though positioned as a universally beneficial transport option for both Europe and Asia, it seems Moscow and Tehran would benefit the most. The two highly sanctioned states, whose connection has recently deepened due to their shared economic isolation from the global economy, could position themselves as lynchpins of an effective transport network.

Unlike Tehran, which still has control over the vital Strait of Hormuz choke point, Russia’s political might in terms of energy transport networks is quickly dwindling after the Baltic states’ complete exit from the BRELL energy system and the West’s resolve to decrease energy dependence. The North-South corridor thereby holds value as a catalyst of global energy transport and trade.

However, this vision is thwarted by financial crises, with workon the railroad from Rasht to Astara in Iran suffering setbacks. Iran does not have the means to pour into the project and has already obtained a 500 million euro loan (about half of the total cost of construction) from Azerbaijan in FDI. In May 2023, it became known that the Kremlin would fund the project themselves by issuing a 1.3 billion euro loan to Tehran, despite Iran’s ballooning debt to Russia. The same month, Marat Khusnullin, Deputy Prime Minister, announced that Russia is expecting to invest approximately $3.5 billion in the North-South corridor by 2030. This is likely a major underestimation of the costs needed to complete the project.

With Iran’s growing debt and Russia’s war-born financial strain, further trade route developments are sure to be delayed. Seeing as the railroad project between Russia, Azerbaijan, and Iran has been in existence since 2005 with no concrete end in sight, the North-South Corridor, despite Russia’s active marketing campaign in light of the troubles in the Red Sea, is unlikely to become a viable transport option in the near future.

The Northern Sea Route (NSR), which Putin has similarly promoted since the start of the Houthi attacks, is likely to suffer a similar fate. The NSR’s realisation as a major global route is hindered by the fact that the Arctic Circle’s harsh climate causes the route to be icebound for about half of the year. Furthermore, in light of the recent war in Ukraine, the NSR is off-limits to even being considered a viable transportation route for large swaths of the West due to sanctions against Putin’s regime.

Russia: Long-Term Strategy

With Russia’s closest regional naval presence being Tartus in Syria, Russia is also interested in establishing naval bases closer to the Red Sea. Russia’s primary interest is to establish a port in Sudan. High-level bilateral negotiations have been actively taking place between Khartoum and Moscow, with an official deal being announced in late 2020. The construction of a naval base would increase Russia’s influence over Africa, facilitating power projection in the Indian Ocean. Nonetheless, the ongoing Sudanese civil war seems to have stalled negotiations.

The region is of such strategic interest to Russia that Moscow has recently pushed forth another alternative for bolstering its presence in the Red Sea: a naval base in Eritrea. During a state visit to Eritrea in 2023, Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov underscored the potential that the Massawa port holds. The same year, a Memorandum of Understanding was signed between the city of Massawa and the Russian Black Sea naval base Sevastopol, in which the two countries pledged to foster closer ties in the future.

A New Axis

China and Russia have recently struck a deal with the Houthis to ensure ship safety, as reported by a Bloomberg article. Under the agreement, ships from China and Russia are permitted to sail through the Red Sea and the Suez Canal without fear of attack. In return, both countries have agreed to offer some form of “political support” to the Houthis. Although the exact nature of this support remains unclear, one potential manifestation could involve backing the Yemeni militant group in international institutions such as the United Nations Security Council. In January 2024, a resolution condemning attacks carried out by the Houthi rebels off the coast of Yemen was passed, with China and Russia among the four countries that abstained.

Despite instances of misfiring by Chinese ships after the deal, the alignment between these countries has been viewed as the emergence of an “axis of evil 2.0." Coined by former U.S. President George W. Bush at the start of the war on terror in 2002, the term “axis of evil” originally referred to Iran, Iraq, and North Korea, which were accused of sponsoring terrorism by U.S. politicians. Indeed, China and Iran have maintained a robust economic and diplomatic relationship. China is a significant buyer of Iranian oil, purchasing around 90 percent of Iran’s oil output, totalling 1.2 million barrels a day since the beginning of 2023, as the U.S. continues to enforce Iranian oil sanctions.

Chinese Dominance of Iranian Crude Oil Exports

Source: Seeking Alpha

However, it may be far-fetched to consider China, Russia, Iran, and North Korea as a united force akin to the Communist bloc against the West during the Cold War. After all, there are significant tensions within these relationships. For example, Beijing has not fully aligned with Moscow regarding the invasion of Ukraine. Additionally, there are power imbalances within these relationships, as Iran relies on China far more than China relies on Iran.

Despite the thinness of this idea of an "axis," it remains concerning that these powerful countries (three of which are nuclear-armed) are aligning against the democratic world. Considering the volume of trade passing through the Suez Canal and the impossibility for the U.S. and company’s Operation Prosperity Guardian to protect every ship in the region, the deal struck between China, Russia, and Iran may be a significant factor that could shift the current global economic balance towards the side of the "Eastern Axis.”

Similarly, China’s recent activities against the Philippines in the South China Sea could be viewed as an attempt to undermine the Philippines’ economy, which heavily relies on its seaports. This could force the Philippines to capitulate or incur significant costs for the U.S. should it decide to provide more assistance to further enhance the Philippines’ defence capabilities.

China: Long-Term Strategy

In recent years, China has increased its ties with countries outside the ‘Western sphere’. Apart from being present in the Gulf of Oman and destining a myriad of vessels to secure the region, it has made strides in developing long-term partnerships with Russia and Iran. Chinese collaboration with Russia is advertised as having “no limits,”, and its 25-Year Comprehensive Cooperation Agreement with Iran further cements its political and economic involvement with both nations.

The security and economic aspects of China’s long-term plans are the most relevant to commodity trade, as violent conflicts and geopolitical tensions are the prime hindrances to trade flows through the region. Nonetheless, the cooperation of these nations does not bode well with the West and could negatively impact trade regardless of improved security.

China’s circumvention of the financial sanctions placed on Iran mocks the international community’s concerted effort to dissuade Tehran’s human rights violations, nuclear activities, and involvement in the Russia-Ukraine war. Its “teapot” strategy, which allowed China to purchase90% of total Iranian oil exports, relies on the use of dark fleet tankers and small refineries to avoid detection and evade the financial sanctions placed on Iranian exports.

Increased its bilateral trade flows with Russia also point to increased cooperation, with $88 billion worth of energy commodities being imported by China in 2022, with imports of natural gas increasing by 50% and crude oil by 10%, reaching 80 million metric tonnes. In 2023, bilateral trade reached $240 billion, proving both countries hold cooperation as a pillar of their economic strategy.

Chinese-Iranian Oil Trade

Source: Nikkei Asia

The West has increased efforts to dissuade cooperation with Russia, as seen with the creation of the secondary sanction authority. These sanctions cut off financial institutions that transact with Russia’s military complex from the U.S. financial system and have successfully led three of the largest Chinese banks to cease transactions with sanctioned companies. Despite the success of certain measures and sanctions, cooperation between both states remains, and their involvement in the Middle East will ensure collaborative efforts for the foreseeable future.

Conclusion

The evident development of collaborative endeavours among the ‘Eastern Axis’ countries is enough to engender strife and uncertainty in trade in the Red Sea. It is becoming increasingly evident that uncertainty will still roam the seas regardless of whether the Houthi conflict is tamed, preventing maritime trade in the Red Sea’s key routes from reaching their potential. The reliance of regional security on both violent attacks and political alignments, such as the involvement of the Eastern Axis in the region, highlights how deeply supply-chain stability is intertwined with geopolitical relations, establishing Iran as a determinant of the Red Sea’s future commodity trade prosperity.

A Strait Betwixt Two

As the Yemeni Houthi group's assault on maritime vessels continues to escalate, the risk to key commodity supply chains raises global concern. As analysed in this series' previous article (available here), conflict escalation impacts the region's security, impacting key trade routes and global trade patterns. The Suez Canal is a key trade route whose stability and security could impact and shift trade dynamics. As the search for alternative trade routes ensues, the Strait of Hormuz makes use of a power vacuum to expand its influence.

Suez Canal

The Suez Canal is a 193-kilometre waterway that connects the Red Sea to the Mediterranean Sea. Approximately 12% of global trade passes through the Canal, granting it vast economic, strategic, and geopolitical influence on a global scale. This canal shortens maritime trade routes between Asia and Europe by approximately 6,000 km by removing the need to export around the Cape of Good Hope and serves as a vital passage for oil shipments from the Persian Gulf to the West. Approximately 5.5 million barrels of oil a day pass through the Canal, making it a ‘competitor’ of the Strait of Hormuz.

Global trade via the Suez Canal is likely to decrease as a result of the rising tensions near the Bab el-Mandeb Strait. Due to their geographic predispositions, the Bab el-Mandeb Strait and the Suez Canal are interdependent; bottlenecks in either trade choke point will have a knock-on effect on the other. Bottlenecks caused by Houthi aggression against ships in the strait are likely to redirect maritime traffic from the Suez Canal to alternative passageways. From November to December 2023, the volume of shipping containers that passed through the Canal decreased from 500,000 to 200,000 per day, respectively, representing a reduction of 60%.

Suez Canal Trade Volume Differences (metric tonnes)

The overall trade volume in the Suez Canal has decreased drastically. Between October 7th, 2023, and February 25th, 2024, the channel’s trade volume decreased from 5,265,473 metric tonnes to 2,018,974 metric tonnes. As the weaponization of supply chains becomes part of regional economic power plays, there is a global interest in decreasing the vulnerability of vital choke points via trade route diversification. The lack of transport routes connecting Europe and Asia has hampered these interests, making choke points increasingly susceptible to exploitation.

Oil Trade Volumes in Millions of Barrels per Day in Vital Global Chokepoints

Source: Reuters

Quantitative Analysis

Many cargoes have been rerouted through the Cape of Good Hope to avoid the Red Sea region since the beginning of the Houthi conflict. Several European automakers announced reductions in operations due to delays in auto parts produced in Asia, demonstrating the high exposure of sectors dependent on imports from China.

In the first two weeks of 2024, cargo traffic decreased by 30% and tanker oil carriers by 19%. In contrast, transit around the Cape of Good Hope increased by 66% with cargoes and 65% by tankers in the same period. According to the analysis of JP Morgan economists, rerouting will increase transit times by 30% and reduce shipping capacities by 9%.

Depiction of Trade Route Diversion

Source: Al Jazeera

More fuel is used in the rerouted freight, an additional cost that increases the risk of cargo seizure and results in elevated shipping rates. The most affected routes were from Asia towards Europe, with 40% of their bilateral trade traversing the Red Sea. The freight rates of the north of Europe until the Far East, utilising the large ports of China and Singapore, have increased by 235% since mid-December; freights to the Mediterranean countries increased by 243%. Freights of products from China to the US spiked 140% two months into the conflict, from November 2023 to January 25, 2024. The OECD estimates that if the doubling of freight persists for a year, global inflation might rise to 0.4%.

The upward trend in freight rates can be seen in the graphic pictured below, depicting the “Shanghai Containerised Freight Index” (SCFI). The index represents the cost increase in times of crisis, such as at the beginning of the pandemic, when there were shipping and productive constraints, and more recently, with the Houthi rebel attacks. Most shipments through the Red Sea are container goods, accounting for 30% of the total global trade. Companies such as IKEA, Amazon, and Walmart use this route to deliver their Asian-made goods. As large corporations fear logistic and supply chain risk, more crucial trade volumes could be rerouted.

Shanghai Containerized Freight Index

Energy Commodity Impact

Of the commodities that traverse the Red Sea, oil and gas appear to be the most vulnerable. Before the attacks, 12% of the oil trade transited through the Red Sea, with a daily average of 8.2 million barrels. Most of this crude oil comes from the Middle East, destined for European markets, or from Russia, which sends 80% of its total oil exports to Chinese and Indian markets. The amount of oil from the Middle East remained robust in January. Saudi oil is being shipped from Muajjiz (already in the Red Sea) in order to avoid attack-hotspots in the strait of Bab al-Mandeb.

Iraq has been more cautious, contouring the Cape of Good Hope and increasing delays on its cargo. Iraq's oil imports to the region reached 500 thousand barrels per day (kbd) in February, 55% less than the previous year's daily average. Conversely, Iraq's oil imports increased in Asia, signalling a potential reshuffling of transport destinations. Trade with India reached a new high since April 2022 of 1.15 million barrels per day (mbd) in January 2024, a 26% increase from the daily average imports from Iraq's crude.

Brent Crude and WTI Crude Fluctuations

Source: Technopedia

Refined products were also impacted. Usually, 3.5 MBd were shipped via the Suez Canal in 2023, or around 14% of the total global flow. Nearly 15% of the global trade in Naphta passes through the Red Sea, amounting to 450 kbd. One of these cargoes was attacked, the Martin Luanda, laden with Russian naphtha, causing a 130 kbd reduction in January compared with the same month in 2023. Traffic to and from Europe is being diverted in light of the conflict. Jet fuel cargoes sent from India and the Middle East to Europe, amounting to 480 kbd, are avoiding the affected region, circling the Cape of Good Hope.

Due to these extra miles and higher speeds to counteract the delays, bunker fuel sales saw record highs in Singapore and the Middle East. The vessel must use more fuel, and bunker fuel demand increased by 12.1% in a year-over-year comparison in Singapore.

In 2023, eight percent, or 31.7 billion cubic metres (bcm), of the LNG trade traversed the Red Sea. The US and Qatar exports are the most prominent in the Red Sea. After sanctioning Russia's oil because of the Ukrainian War, Europe started to rely more on LNG shipments from the Middle East, mainly from Qatar. The country shipped 15 metric tonnes of LNG via the Red Sea to Europe, representing a share of 19% of the Qatari LNG exports. Vessels travelling to and from Qatar will have to circle the Cape of Good Hope, adding 10–11 days to travel times and negatively impacting cargo transit.

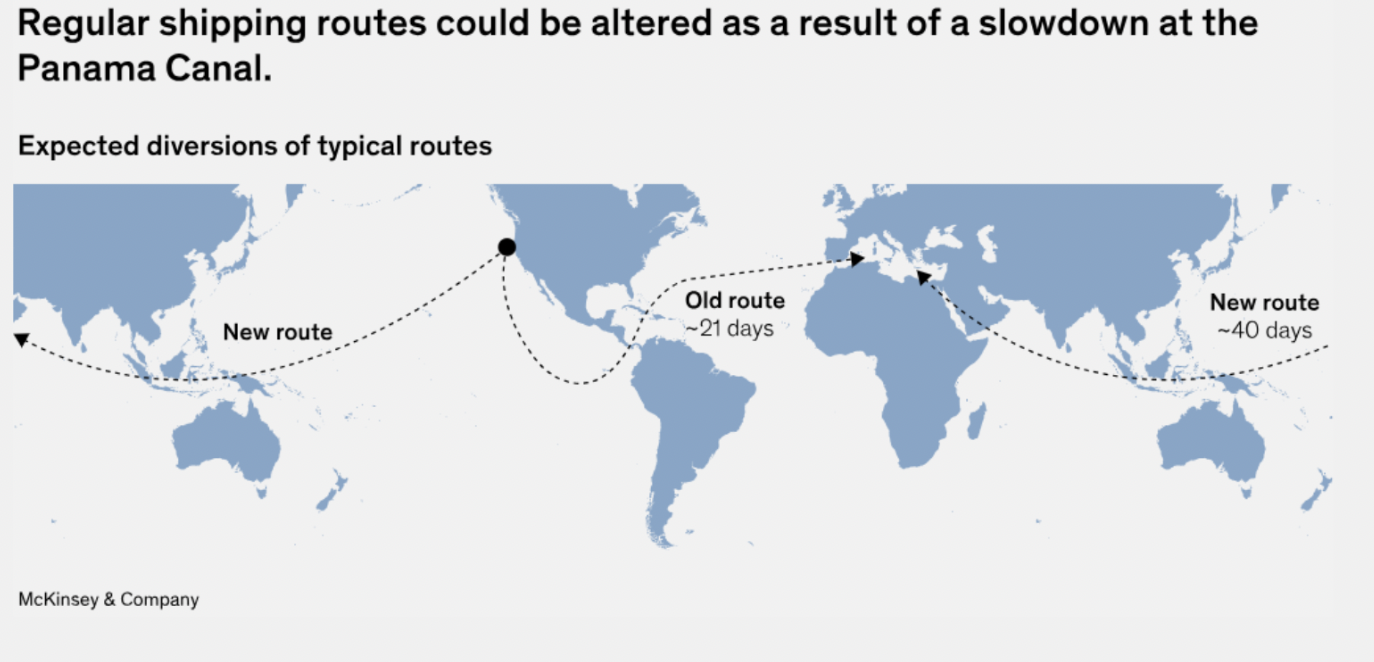

US LNG export capacity has increased in the past few years, sending shipments to Asia via the Red Sea. The Panama Canal receives many LNG cargoes from the US via the Pacific, yet its traffic limitations cause US cargo to be routed through the Atlantic and the Red Sea. The figure “Trade Shipping Routes” below displays the dimensions of the shifts that US LNG cargoes must take in the absence of passage via the Panama Canal.

Trade Shipping Routes

Source: McKinsey & Company

Until January 15, at least 30 LNG tankers were rerouted to pass through the Cape of Good Hope instead. Russia's LNG shipments to Asia are currently avoiding the Red Sea, and Qatar did not send any new shipments in the last fortnight of January after the Western strikes at Houthi targets.

Risk Assessment

A share of 12% of oil tankers, ships designed to carry oil, and 8% of liquified gas pass through this route towards the Mediterranean. Inventories in Europe are still high, but if the crisis persists for several months, energy prices could be aggravated. As evidenced by the sanctions against Russia, cargo reshuffling is possible. Qatar can send its cargoes to Asia, and those from the US can go to European markets, allowing suppliers to effectively avoid the Red Sea.

Around 12% of the seaborn grains traversed the Red Sea, representing monthly grain shipments of 7 megatonnes. The most considerable bulk are wheat and grain exports from the US, Europe, and the Black Sea. Around 4.5 million metric tonnes of grain shipments from December to February avoided the area, with a notable decrease of 40% in wheat exports. The attacks affected Robusta coffee cargoes as well. Cargoes from Vietnam, Indonesia, and India towards Europe were intercepted, impacting shipping prices and incentivizing trade with alternative nations.

Daily arrivals of bulk dry vessels, including iron ore and grain from Asia, were down by 45% on January 28, 2024, and container goods were down by 91%. However, further significant disruptions to agricultural exports are not expected. Most of the exports from the US, a large bulk, were passing through the Suez Canal to avoid the congestion of the Panama Canal due to the droughts that limited the capacity of circulation. These cargoes are now traversing the Cape route.

Around 320 million metric tonnes of bulk sail through Suez, or 7% of the world bulk trade. No significant impacts are predicted for iron ore or coal, which represented 42 and 99 megatonnes of volume, respectively, shipped through the Red Sea in 2023. Most of the dry bulks that traverse the impacted region can be purchased from other suppliers, precluding significant supply disruptions.

As of March 1st, reports show that only grain shipments and Iranian vessels were passing through the Red Sea. There were no oil or LNG shipments with non-Iranian links in the Red Sea. These developments illustrate the significant trade shifts caused by the Red Sea crisis. As of today, a looming threat lies in the Houthis’ promises of large-scale attacks during Ramadan. The lack of intelligence on the Houthi’s military capacity and power makes it difficult to ascertain the extent of future conflicts, generating further uncertainty in commercial trade.

The Strait of Hormuz

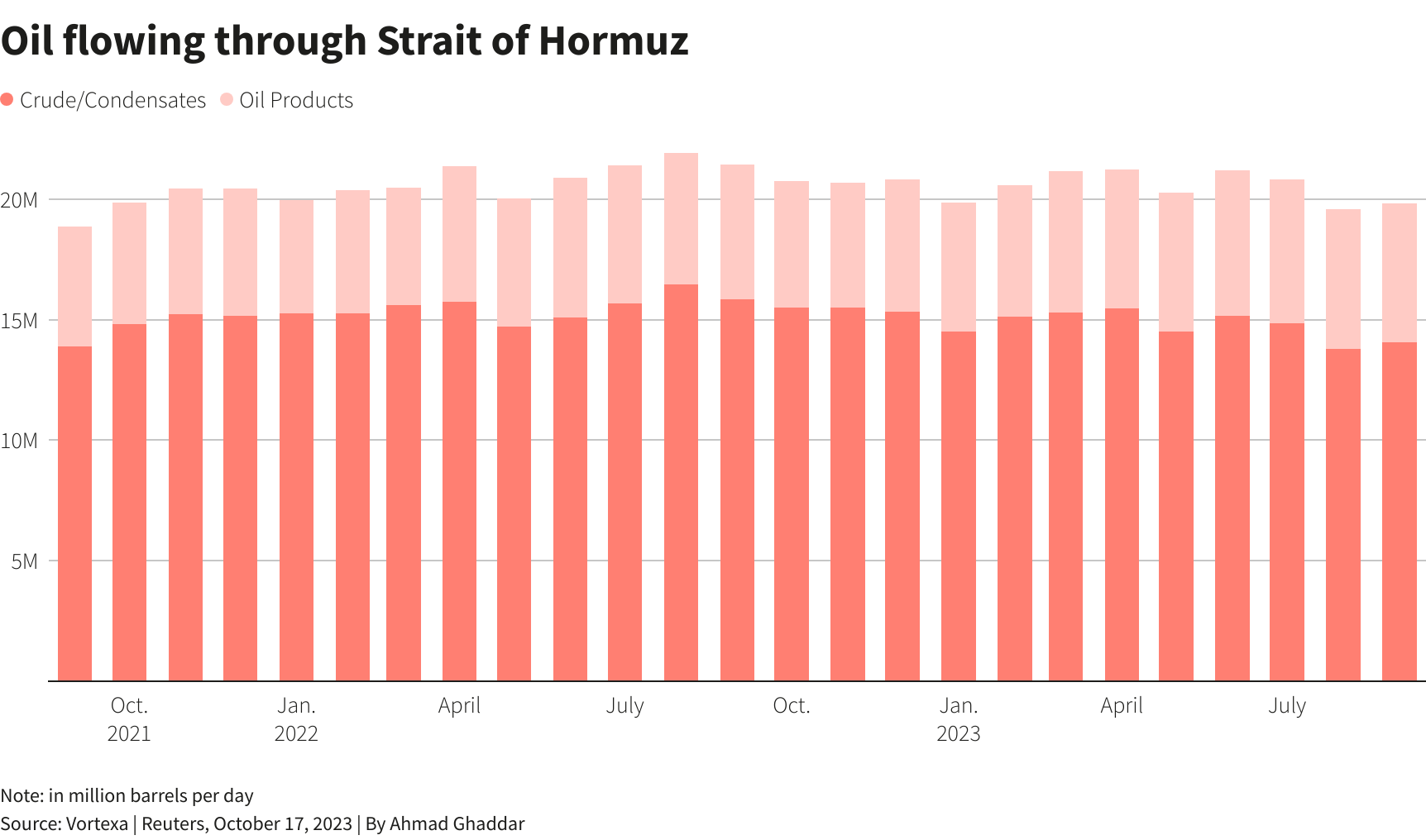

The Strait of Hormuz is a channel that connects the Persian Gulf to the Gulf of Oman, providing Iran, Oman, and the UAE with access to maritime traffic and trade. The strait is estimated to carry about one-fifth of the global oil at a daily trade volume of 20.5 million barrels, proving to be of vital strategic importance for Middle Eastern oil supply the world’s largest oil transit chokepoint. The strait is a prominent trade corridor for a myriad of oil-exporting nations, namely the OPEC members Saudi Arabia, Iran, the UAE, Kuwait, and Iraq. These nations export most of their crude oil via the passage, with total volumes reaching 21 mb of crude oil daily, or 21% of total petroleum liquid products. Additionally, Qatar, the largest global exporter of LNG, exports most of its LNG via the Strait.

Geographic Location of Strait of Hormuz

Source: Marketwatch

Although the strait is technically regulated by the 1982 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, Iran has not ratified the agreement. Through its geostrategic placement, Iran can trigger oil price responses through its influence on trade transit, establishing the country’s regional and global influence.

Strait of Hormuz Oil Volumes

Source: Reuters

Experts are particularly worried that the turbulence is likely to spread to the Strait of Hormuz now that Iran backs the Houthis in Yemen and might want to support their cause by doubling down regionally. However, this is something that would cause a lot of backlash in the form of a further tightening of economic sanctions against Tehran, which might deter further provocations.

Despite Iran’s previous threats to block the Strait entirely, these have never gone into effect. Diversifying trade routes to avoid supply shocks and bottlenecks is of interest to regional oil-exporters dependent on the route for maritime trade access. Such diversification attempts have already been undertaken, as seen by the UAE and Saudi Arabia's attempts to bypass the Strait of Hormuz through the construction of alternative oil pipelines. The loss of trade volume from these two producers, holding the world's second and fifth largest oil reserves, respectively, severely hindered the corridor’s prominence.

The attacks on the Red Sea might cause damage to the oil and LNG cargo from countries in the Persian Gulf, increasing costs for oil and gas exporters. However, cargoes could find alternative destinations. The vast Asian markets, which face a shortage of energy products due to a loss of trade through the Red Sea, could be a potential suitor. Finding new LPG (liquefied petroleum gas) contracts could be beneficial for Iran, and its recently enhanced production capacity could supply various markets.

Geopolitics and Prospects for a Route Shift

Although the Strait of Hormuz stands to capture diverted trade flows from the Suez Canal, its global influence is still limited by Iran’s geopolitical ties. As exemplified by the Iran-US conflict, Iran’s conflicts can severely impact traffic through the Strait, significantly impacting the stability of the route and prospects for future growth.

Although security and stability are of paramount importance to trade, efforts to provide these traits could be counterproductive. On March 12th, China and Russia conducted maritime drills and exercises in the Gulf of Oman with naval and aviation vessels. According to Russia's Ministry of Defence, this five-day exercise sought to enhance the security of maritime economic activities using maritime vessels with anti-ship missiles and advanced defence systems. Over 20 vessels were displayed in this joint naval drill, attempting to lure trade through the promise of stability and security.

Whether meant as a display of power or a promise of security, the pronounced presence of Russian and Chinese forces could aggravate geopolitical tensions and increase the potential for conflict in the region, driving global trade prospects down. With precedents of trade conflict, such as the IRGC’s seizure of an American oil cargo in the Persian Gulf on January 22nd, various countries might be sceptical of rerouting commodity trade through the Strait.

Tensions are also aggravated by Iran’s alleged assistance in the Houthi attacks. The US has supposedly communicated indirectly with Iran to urge them to intervene in the region. China and Russia’s interest in improving the Strait’s trade prospects would benefit from a de-escalation of the Houthi conflict, as shown by China’s insistence on Iran’s cooperation in the Houthi conflict. As the conflict stands, the Strait’s prospect as an alternative trade route is dependent not only on Iran’s reputation and presence in global conflicts but also on the route’s patrons and proponents.

Conclusion

The extent to which the Strait of Hormuz could benefit from trade diversion depends not only on its ability to pose itself as a viable trade route but also on the duration of the Houthi conflict. In order to capture trade volumes and increase international trade through the route, Iran would have to ameliorate its geopolitical ties and provide stability to compete with rising prospective trade route alternatives. Although the conflict in the Suez has yet to show promising signs of de-escalation, securing the Suez would likely cause previous trade volumes to resume and restore its hegemony in commodity trade. It remains to be seen whether the conflict will endure long enough to allow other trade routes to be established as alternatives and permanently shift power balances in global trade.

The 2024 BRICS Expansion: Risks & Opportunities

With its 15th summit on August 2023 BRICS gained increased attention. The main focus of the summit was on the potential enlargement of BRICS by admitting new members. During the summit, it was announced that 6 countries - Argentina, Egypt, Ethiopia, Iran, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates - had been invited to join the group, with their official entry into the bloc set to take place in January 2024.

The expansion of BRICS has raised questions regarding the implications for international politics and economics. And while most analysts seem to agree that it means something significant, it remains unclear what exactly. This report, therefore, analyses the potential risks and opportunities of the expansion, with a particular focus on the commodities sector. Our analysis addresses questions regarding the interests of BRICS+ countries, the challenges and opportunities for the bloc itself, and the wider commodities sector.

North African Energy Market Analyis: Libya

On the 3rd of July, Khalifa Haftar, head of the Libyan National Army, threatened to use armed force unless the politically fragmented country could agree on a mechanism for the “fair” distribution of oil revenues. The deadline set by the military leader is 31 August (today). The potential for another civil war is high and this will have large implications for major commodity markets like crude oil as well as natural gas. The intervention of regional and extra-regional powers further complicates Libya’s chaotic political situation, with different countries backing opposing governments.

Read here for London Politica’s latest report on the situation in Libya, a collaborative analysis from team members from Global Commodities and MENA Watch research programmes.

An EU Hope: Sourcing Critical Raw Materials from South America

Expansion of the EU’s raw material supply agreements with South America.

In light of the Russian-Ukraine conflict, European countries have been facing a raw material supply crisis. Disrupted supply chains have significantly contributed to the rise in the price of critical minerals, causing lithium and cobalt to double and other essential energy commodities such as gas to increase 14-fold in price over the span of 3 years. The EU has sought new trade partners to mitigate price rises and reduce their dependence on countries such as China and the US, aiming to secure a sustainable supply chain of critical raw materials. The prime candidates for this venture have been South American countries, a region with cultural and historic ties to the EU. Countries in this region are characterised by an abundance of natural resources and arable land, and their economic reliance on commodity exports provides an incentive to create trade partnerships. As a consequence, recent years have seen efforts to develop bilateral relations and trade in goods and services with the EU.

Recent Developments

The most recent development in the EU’s bid to secure critical raw materials has been intensified cooperation with Argentina. President Alberto Fernández and European Commission head Ursula von der Leyen signed a memorandum on June 13 to expand cooperation between Argentina and the European Union in sustainable value chains of critical raw materials. The goal of the agreement is to guarantee a steady and sustainable supply of commodities needed to ensure the clean energy transition, namely minerals, for European countries. The agreement is collaborative in nature, as the EU plans to invest in research and innovation in Argentina, with a special focus on minimising the climate footprint of extractive activities such as mining. While the EU secures a steady inflow of commodities, Argentina profits from quality job creation, increased sustainability, and economic growth from commodity exports, boosting its staggering economy.

Mercosur

Argentina, along with eleven other South American countries, make up the regional trade bloc Mercado Común del Sur (Mercosur). Trade between the EU and Mercosur is plentiful, with the EU being Mercosur's largest trade and investment partner. As of 2021, the EU exported €45 billion to and imported €43 billion from Mercosur. The EU imports mostly mineral and vegetable commodities and exports machinery, appliances, chemicals, and pharmaceutical products. In 2019, the EU sought to intensify this partnership by establishing a political agreement with decreased trade frictions, namely tariffs for small and medium sized enterprises, creating stable rules for trade and investment, and establishing environmental regulations and policies in all Mercosur countries. This agreement, however, has remained in a provisional stage ever since, as efforts to reach a consensus have been stunted by certain conflicting interests.

Graphical Representation of Main EU Imports from Mercosur from 2011 to 2021

Source: Eurostat

Cooperation Friction

There are various conflicting interests that prevent this deal from going through. For one, Brazil, Mercosur's largest economy, has plans for intensified cooperation with China, one of its main trade partners. Argentina has also increased cooperation with China in recent years, adding to tensions in EU relations. Brazilian President Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva, the current Mercosur president, has also expressed his disapproval of the proposed agreement. Brazil has had intense deforestation in recent years, and although the current Brazilian presidency has decreased these efforts, policies proposed by the EU in the agreement would interfere with domestic policy and development in their agricultural production. Various clauses prohibit the export of products from deforested areas, demand strict labour laws, and provide public procurement rights to EU and Mercosur companies, limiting the Brazilian government's agricultural and industrial policies and weakening its ability to control domestic production autonomously. Lula has taken a stand against this interference and denounces the agreement for reducing South American countries to indefinite commodity suppliers to Europe.

Various producers in European countries have also voiced their discontent with the deal. With lower commodity prices arising from reduced tariffs and trade restrictions, farmers and raw material producers in these countries would face extremely low prices and struggle to remain competitive. In France, local farmers fear losing profits as a result of an inflow of cheap imported beef. Despite expressing their interest in creating exceptions for agricultural products, farmers know these provisions would be unpopular with Mercosur producers and are thus unlikely to be included in the agreement. Although these farmers’ influence is not as prominent as that of other actors, protests and disruptions have been a cause for concern in the past. There is the possibility of further aggravating the current clashes over pension reforms, which place the French government in a delicate situation. EU member states could face scrutiny if the pact goes through for neglecting local producers and destroying domestic markets, although this might be a risk governments are willing to take in order to secure energy commodities.

Environmentalist organisations also oppose the agreement. Greenpeace has encouraged protests in Brussels against the "poisonous treaty" that aims to increase trade in environmentally detrimental commodities. A particular disapproval of the lower export prices of pesticides was cited in their protests, along with the more pressing matter of deforestation for cultivation in Brazil. These perspectives are shared by various member states in the EU, and their combined efforts have provided advances in the vein of sustainability. In various dealings, member states such as Austria, France, Ireland, Luxembourg, and Belgium have advocated for enforceable provisions regarding environmental issues, and their veto power places pressure on other member states to comply.

Future Prospects

The EU’s most recent supply acquisition, Argentina, will soon face political change that could affect their cooperation. Unlike Lula, who has three years left in his term, Argentine President Alberto Fernandez will be out of office as of December of this year, and the new government could increase friction in the agreement. Various candidate parties in Argentina have ideologies that differ greatly from Lula’s left-leaning policies, and their contrasting economic plans could decrease both bilateral relations and cooperation in Mercosur. Furthermore, the Mercosur deal, along with the bilateral agreement between Argentina and the EU, stipulates environmental policies and regulations for the country’s extractive activities that could slow their development. With Argentina planning on hastily developing oil and gas extraction in Vaca Muerta, these stipulations could very well be violated and harm both deals with the EU. This applies to many Mercosur countries that rely on primary activities but also want to develop other sectors that may have negative environmental impacts, namely industrial production. With economic growth being the main focus of Mercosur states, it is unlikely that they will accept a deal that would hinder development of any kind.

As seen, the political inclinations and plans for economic development of each Mercosur country have vast implications for the bloc’s ability to close a deal with the EU. With Lula’s rise to power, a change in government policy, in this case a decrease in deforestation, favoured the EU’s intention of creating a clean energy supply chain and reinvigorated expectations for cooperation. Nonetheless, the environmental implications of most Mercosur countries’ production models and their cooperation with countries like Russia and China create distrust between both blocs and stunt advances in the agreement. It seems that the EU’s inability to renegotiate environmental policy due to pressure from environmentalist organisations and specific member states will require a complacent Mercosur to finalise dealings. Although the possibility of splitting the agreement into two different parts exists, thus circumventing sustainability policy, it is unlikely the bloc will follow this path as it would aggravate various member states. Mercosur’s strong conviction for sovereignty will prevent them from accepting the stringent regulations currently proposed by the EU, and the EU’s apparent unwillingness to cede certain stipulations will further aggravate tensions between blocs and cause dealings to remain stagnant. With many South American countries undertaking long-haul projects on agricultural production and extractive activities with potential environmental implications, such as Argentina’s 10-year oil pipeline investment, the agreement will likely continue to face conflicts for the next two to five years. Although Lula promised at the July summit with the EU to deliver a definite proposal that is “easy to accept” soon, his declarations against the last draft’s stringent nature put into question whether this version will comply with the requirements stipulated by the EU. As demand from alternative countries like China grows, Mercosur will be less inclined to accept terms that harm its development, causing dealings to drag on until the EU complies.

Catching Up to The Rat Race: Operation Expansion in Vaca Muerta

Argentina is home to the second and fourth largest non-conventional shale oil and gas deposits in the world, respectively. Known as Vaca Muerta, this shale field spans over 7.5 million acres and harbours around 308 trillion cubic feet of non-conventional gas and an estimated 16.2 billion barrels of oil. Since extraction activities began in 2011, Vaca Muerta has been the subject of political and social strife, causing setbacks in production and infrastructure development, preventing it from reaching its output potential. In recent years, joint efforts from the Argentine government with gas and oil companies, namely Yacimientos Petrolíferos Fiscales (YPF), Exxon and Petronas, have reinvigorated expectations for a new 'shale boom'.

YPF’s Ambitions

At the forefront of production revitalisation efforts lies the majority state-owned company YPF. Earlier this March, the energy company announced their five-year plan to double their oil output and raise natural gas production by 30% through the expansion of operations in Vaca Muerta. Of the $5 billion in capital expenditure guidance put forth by the company, $2.3 billion will be allocated to operation expansions in Vaca Muerta.

Nearly $700 million will be invested in infrastructure to support the growth in output, namely oil and gas facilities, with the main growth expected in unconventional reservoirs. YPF has also partnered with major oil superpowers on various projects. Shell revealed plans to invest $300 million in YPF's five year plan, seeking to reach daily production of 15,000 barrels by 2024. A $10 billion joint venture with Petronas will develop a 640 km pipeline from Vaca Muerta to the Buenos Aires province, connecting with the north pipeline systems. This pipeline will be concluded in 10 years and will provide a liquified natural gas (LNG) capacity of 25 million tons per year.

On June 20 2023, the construction of the Presidente Nestor Kirchner (PNK) pipeline began, requiring a $2.7 billion investment that will allow a daily gas transport increment of 11 million cubic metres. This investment is arguably the most important development in terms of infrastructure, as it will provide ease of transport within Argentina to neighbouring countries. This represents the Argentine government’s ambition to make Argentina an energy exporter, establishing itself as the main gas and oil provider to South American countries.

Illustration of Presidente Nestor Kirchner Gas Pipeline (Yellow Line)

Source: Energía Argentina

Shale Déjà Vu

Vaca Muerta has been touted as the protagonist of a new Shale boom by many, yet its performance as of late has contradicted these bold claims. Unlike the United States, site of the latest Shale revolution, Argentina struggles with immense political risk and economic instability. In this year alone, annual inflation is forecast at 146%, and the economy is set to shrink by 3% relative to 2022. The country is extremely polarised and ideologically divided, causing parties with conflicting ideals to come into power and then deviate from the previous governments' efforts. This lack of consistency and stability has led to various defaults, rising deficits, and stagnant projects that have inhibited the growth of the oil and gas extraction sector.

The Argentine shale reserves are comparable to the US', with an estimated 30 billion fewer recoverable oil barrels and 137 trillion more cubic feet of shale gas. It was the US’ superior pipeline infrastructure and favourable government policy, however, that facilitated its shale expansion. Current estimates provided by McKinsey & Company place Vaca Muerta breakeven prices at $36 per barrel of oil and $1.6 per million British thermal units for gas, providing ample opportunity for investment payoff. The current potential output of shale reserves in Vaca Muerta far exceeds the capacity of pipelines and extraction systems. In fact, production is already overwhelming workers in extraction facilities, and the expansion initiatives will only be able to meet output growth in the long run. The US, on the other hand, was able to expand its pipeline infrastructure to meet growth and output standards. The use of subsidies, tax credits, and reductions in drilling expenses also provided increased profitability that drove investments and allowed drilling operations to grow rapidly in the US. The previous Argentine government changed the interpretation of subsidies and removed support from energy companies, causing millions in losses for foreign companies. The current government has reinstated many subsidies to the sector, yet these changes between governments cause uncertainty that deters foreign investment and opportunities for growth.

Risks

Argentina is set to have elections in October, where the country will change its president, vice president, members of Congress, and governors. The current president has announced he will not run for president, and the remaining prospective political parties differ greatly in their approaches to governance. The fierce opposition between these parties will generate issues within Congress and make passing laws and approving state projects more difficult, potentially harming government projects or regulation changes to incentivise growth in Vaca Muerta. One of the main presidential candidates, Javier Milei, has voiced his plan to completely privatise YPF to prevent it from being used as a political tool. His plans for Vaca Muerta include implementing a consistent long-term production growth plan that alters the legal framework of the sector. This approach aims to reduce the power of the government, much like many of his other policies, and clashes greatly with the other political parties. The main opposition party, Juntos Por El Cambio, aims to foster the sector's growth by increasing the government's involvement in the form of subsidies and state investments, ultimately driving economic growth. The differences between candidates, and the current economic conditions, create uncertainty that makes Vaca Muerta a poor investment choice for many. Fear of privatisation also weighs on the sector, as a reduction of the state’s involvement would interfere with the current pipeline projects that are dependent on government funding.

For years on end, local indigenous people have voiced their disapproval of oil and gas extraction activities in Vaca Muerta. The Mapuche people have asked the government to review their plans for the new PNK pipeline to make sure it does not interfere with indigenous communities. Their concern for the environmental impact of these activities is also shared by various activist groups. Although the issue has not caught the attention of international organisations yet, many anti-fracking associations have begun to take notice. Various domestic activist groups, such as Greenpeace and Confederación Mapuche de Neuquén, have worked in cohort with local communities to cause disruptions by blocking extraction and construction sites, resulting in great losses in production. The construction of new pipelines has greatly aggravated these groups, promising issues in the near future. The extraction sector relies heavily on these pipelines, so the vulnerability to protests and further delays in construction is extremely high.

Recently, the International Rights of Nature Tribunal opened a case against fracking activities in Vaca Muerta. A delegation of the organisation concluded their visit to Vaca Muerta and presented their findings to the Deputy Chamber of the Argentine National Congress. In the presentation, the delegation highlighted water pollution, lack of water availability, damage to wildlife, and loss of fertile land in Rio Negro and Neuquen were a direct result of extraction activities. This initiative is one of many attempts to pressure Congress to enact laws that will safeguard the environment and surrounding indigenous communities. The laws and regulations that could result from these efforts would hinder extraction activities by disincentivizing companies from investing in the region through legal and financial sanctions, greatly impacting the development and profitability of the Vaca Muerta project. As extraction operations continue to expand and oil and gas production increases, these groups will likely intensify their efforts and take advantage of the delicate break-even balance of projects to pressure relevant authorities.

Future Prospects

Argentina still has the chance of experiencing a shale boom. All major political parties have expressed their interest in developing Vaca Muerta to facilitate the country’s economic recovery, although their methods differ. Taking the US as an example would suggest that parties that increase subsidies and tax breaks would be the most successful, but Argentina’s situation differs vastly from the US and should not follow the same exact path. Both approaches to expansion, privatisation and increased government involvement, seek to foster growth and monetise Vaca Muerta to establish Argentina as a shale powerhouse. As long as the government’s ambitions remain constant and funds don’t falter, a path to growth is possible.