Intelligence Report - Private military contractors on the Ukraine-Russia war: a mapping of their involvement

Analysts: Marina Tovar, Alex Brookes, Erlend Hokholt, Mathilda Minakova, Olivia Gibson and Geri Kocsis

The legal status of the involved parties in the conflict

Since Russia invaded Ukraine on the 24th of February, 2022, the role of Private Military Contractors (PMCs) and private military companies operating in Ukraine has increased. Job announcements, such as “multilingual former soldiers willing to covertly head into Ukraine for $2000 per day - plus bonus”, were and have been present throughout the conflict. However, to what extent can we affirm that there are PMCs in Ukraine? As a legal matter, PMCs are illegal under the Russian constitution, which reserves the Russian government and the state all matters related to security and defense. On the other hand, the Ukrainian government launched a website calling for international volunteers to join the fight in Ukraine, named the International Legion of Defence of Ukraine. Therefore, we observe the extended presence of irregular combatants, at-first-glance PMCs, silent professionals, and the military. As the Ukraine conflict is classified as an international armed conflict (IAC), it is governed by the four Geneva Conventions, the Additional Protocol I (API), which both Ukraine and Russia have signed and ratified, and International Humanitarian Law (IHL). This section aims to provide insight into the legal differences between the parties involved in the conflict and shed light on the limitations of the definition of PMCs. This is necessary because significant online media outlets, traditional media, and social media platforms have used this term wrongfully.

Combatants

In IACs, the term combatants are defined as the individuals belonging to the armed forces of the parties involved in the conflict; being the armed forces, “all organized armed forces, groups or units under a command responsible to the party of the conflict”. According to the Geneva Conventions, combatants have the right to take part in hostilities and enjoy some privileges, like affording the status of Prisoner of War (POW) in the event of capture.

Foreign volunteers and foreign fighters

Foreign volunteers joining the International Legion of Defence of Ukraine have been incorporated into Ukraine's Territorial Defence Forces; therefore, being considered a foreign military unit falling under the control of one of the parties involved in the conflict. If they had not been incorporated into Ukraine's military, they would initially be categorized as members of non-state armed groups. As the members of the International Legion are part of Ukraine’s military, they become combatants entitled to POW status. Nevertheless, classifying International Legion’s members under combatants is not straightforward; for example, Russia announced they could fall under the category of mercenaries and, therefore, not be entitled to POW status.

Foreigners joining pro-Russian separatists in disputed regions like the Donbas, Luhansk, Kharkiv, and Kherson are classified as foreign fighters. Despite that, the Ukraine-Russia war is classed as an IAC as it is an armed conflict between two states, the separatist regions that are independent republics according to Russia, fall under the category of a non-international armed conflict (NIAC) according to the API. Therefore, Pro-Russian foreign fighters in these regions would not be entitled to POW status and would be classified differently from foreigners joining the Russian armed forces in other regions, who would be classified as combatants.

In this line, foreigners joining Ukraine’s or Russia’s military forces and acquiring combatant status if they commit a terrorist offense could be prosecuted under their national legislation. The application of terrorism legislation and International Humanitarian Law is not incompatible. A foreigner could follow IHL and the Geneva Conventions applicable to the conflict they are participating in but commit terrorist offenses not prosecuted by IHL but are by their national legislation. For example, individuals from Australia or the Netherlands joining the International Legion or the Russian military could be prosecuted for terrorist-related offenses.

Private military contractors and mercenaries

Legally speaking, as we have previously acknowledged, the Russian government denies using PMCs, like the Wagner Group, Patriot, and Task Force Rusich, in the ongoing war. However, the Russian government relies on these irregular forces and mercenaries or silent professionals to complement the tasks the Russian military is undertaking in Ukraine. The media has indistinctly used the terms PMCs and mercenaries as both work for money. However, PMCs recruit individuals within an organization, and mercenaries are individual soldiers hired by whoever pays them. Article 47 of the First Additional Protocol to the Geneva Conventions (AP I) defines a mercenary as any individual who meets the six criteria contained in said article:

“a) is specially recruited locally or abroad in order to fight in an armed conflict; b) does, in fact, take a direct part in the hostilities; c) is motivated to take part in the hostilities essentially by the desire for private gain and, in fact, is promised, by or on behalf of a Party to the conflict, material compensation substantially in excess of that promised or paid to combatants of similar ranks and functions in the armed forces of that Party; d) is neither a national of a Party to the conflict nor a resident of territory controlled by a Party to the conflict; e) is not a member of the armed forces of a Party to the conflict; and f) has not been sent by a State which is not a Party to the conflict on official duty as a member of its armed forces.”

This definition, therefore, presents high complications and challenges as to defining if there are mercenaries in the Russia-Ukraine war. Firstly, Article 47 definition requires that individuals are motivated to take part in conflicts "by the desire for private gain". Fighters' motivation can change throughout the conflict and have complementary motivations, such as patriotism, private gain, humanitarianism, or others. Therefore, the motivation element in article 47.2 is challenging to determine due to the hierarchy of motivations and the uniqueness and exclusivity of private gain as the main driver for an individual to fight. Secondly, the narrowness of the definition makes that parties in the Ukraine-Russia conflict do not fall under this category, like members of the Legion, as they have been incorporated under Ukraine's military and thus not complying with the article's 47 requisites.

To what extent can Russia’s proxy groups, like the Wagner Group, Task Force Rusich, and Patriot, be considered mercenaries? Russia has thoroughly relied on non-state groups in military operations, like Syria, Libya, Sudan, and Madagascar, among others, including Ukraine. Although these groups could comply with some of the formal elements in article 47, like the lack of armed forces status, motivation, and residency, it is unclear whether they meet the excess compensation requirement. Moreover, determining if individuals recruited for private military companies meet the requirement to be “specially recruited (...) to fight in an armed conflict” and “take direct part in the hostilities” as some tasks the Wagner Group and Task Force Rusich do are intelligence gathering, military training, thus not directly fighting on the conflict.

Therefore, in the legal domain, it is very unlikely that there are mercenaries in Ukraine. Concluding if the Wagner Group and Russian-affiliated non-state actors participating in the Ukraine-Russia war are indeed mercenaries is difficult due to the problems we have stated above. However, after providing a legal clarification of these terms and setting a ground, we will describe Russian-affiliated non-state actors as PMCs, Ukrainian-affiliated parties, like the Legion, as international fighters, and US-affiliated non-state actors as PMCs.

2. Russian private military contractors

Russia’s motivations to use private military contractors

Russia has used PMCs as an essential part of modern asymmetrical warfare tactics. PMCs are oftentimes seen as a private extension of the Russian forces used as a tool to pursue geopolitical goals across the globe. There are several reasons why Russia uses them instead of regular forces. Russian PMCs, such as Wagner, have operated and continue to intervene in different theatres of wars worldwide, such as in Syria, Libya, and the Central African Republic (CAR). They give the ability to project Russian power and influence in a “weight class” over themselves in political and economic issues. PMCs support Russian partners and allies through military interventions and intelligence gathering. In addition, they contribute to protecting Russian economic interests, like mining and oil resources, and contribute to the expansion of trade in the developing world. Finally, they are a source of soft power: they expand Russia’s sphere of influence, contributing to the spread of a Russian “ideology”, and promoting a Russian narrative through information campaigns and disinformation operations.

The use of PMCs provides the Russian government with the possibility of deniability when conducting military operations. As mentioned earlier, PMCs are illegal in Russian law, and therefore, the use of PMCs is denied officially by the Russian government. This vague and confusing connection between the state and PMCs provides a grey zone for Russian PMCs to operate in. In the Ukraine war, PMCs have made it possible for the Russian government to deny war crimes and hide Russian casualties. After the increasing casualties in Ukraine, have Russian forces been more reliant on PMCs to contribute to recruits in the fight.

The Wagner Group

The Wagner Group was founded in 2014 by a veteran of the Second Chechen War, Dmitriy Valeryevich Utkin, and has been a critical asset in achieving Russian foreign policy objectives in the Middle East, Africa, and Ukraine. Utkin's last public appearance was in 2016, as Yevgeny Prigozhin, Putin’s caterer at the Kremlin, rose in prominence within the organization and became the de facto leader of the PMC. Prigozhin's rise is largely explained by his ability to forge close unofficial ties with the Russian President and, to this day, become an oligarch, managing different Russian companies, including the Wagner Group.

The Wagner Group is deeply integrated within the Russian intelligence community and used as a branch for its foreign operations. In January 2023, the Wagner Group became a legal entity in Russia as it registered as a joint-stock company in St. Petersburg. A joint stock company named “PMC Wagner Center” was registered, describing its activities as “businesses, management consulting, publishing, media, and others”. To this day, the number of Wagner combatants operating in Ukraine amounts to 50,000 servicemen, of which 10,000 are military contractors while the remaining 40,000 are conscripts recruited from Russian prisons. Other sources claim that the number of Wagner Group members operating in Ukraine is around 20,000.

Over the years, the Wagner Group has become the preeminent Russian PMC, thanks to the political and military savviness of its leader, Yevgeny Prigozhin, with operations spanning different countries and continents. Their first deployment in Ukraine is attested during the invasion of the Crimean peninsula and the following war in Donbas, in which members trained local forces, provided logistical support, and fulfilled other security operations, such as safeguarding important sites. As Russia invaded Ukraine in February 2022, their use has substantially increased and changed in light of the military shortcoming of the Russian Ministry of Defence (MoD) in handling military operations during the invasion.

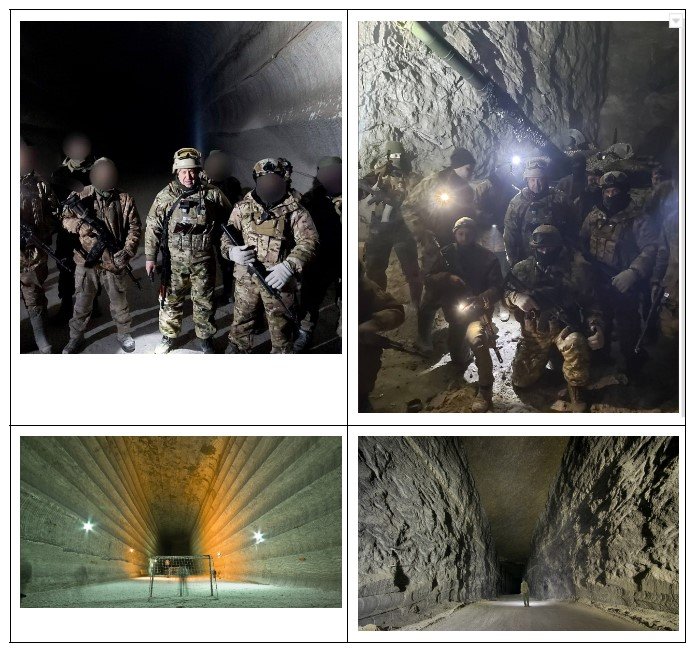

Russia has actively deployed Wagner combatants to conduct military campaigns, like Soledar’s capture to encircle Ukrainian forces in Bakhmut. In the following table, we analyze the role of the Wagner Group and its leaders in Soledar’s capture. The video, reported by the Dossier Centre, an organization founded by Mikhail Khodorkovsky to expose high-level Russian corruption, identifies Prigozhin near Soledar, Ukraine. Wagner soldiers are reportedly located in a Salt tunnel near Soledar; the first two images are reportedly Wagner members, and the two followings, are a comparison of the tunnel of a salt mine.

The Russian MoD has been supplying military equipment to the Wagner Group deployed in Ukraine with “TOS-1A thermobaric artillery system,, various self-propelled guns and mortar systems, several armored vehicles, and an Su-25 aircraft”, as well as provided logistical support on how to use it in the areas of Bakhmut. German intelligence claimed that the Wagner Group was responsible for massacres in Bucha in 2022.

However, lately, the Wagner Group’s presence in the Ukraine-Russia war has led to limited military successes, such as the above-mentioned capture of Soledar and political infighting between the Russian MoD and the PMC. Prigozhin, on various occasions, criticized the Russian army’s military shortcomings and débacles, who, in response, have not credited the Wagner Group for the capture in Soledar. US intelligence confirmed the existence of the political turf and rivalry between the Russian MoD and the PMC. The appointment of Valery Gerasimov as the top commander of Russian forces in Ukraine was depicted as an attempt by Putin to restore the hierarchy between the Russian MoD and the Wagner Group. More recently, the US Government listed the Wagner Group as an international crime organization. Prigozhin sent an official letter demanding the US government to “clarify what crime was committed by the PMC Wagner?” On the latest advancements of the group, we observe this video, dated January 22, 2023, where the Wagner Group members are advancing in the south of Bakhmut, where there are heavy casualties.

Task Force Rusich

Task Force Rusich (better known as simply Rusich), a nationalist, Neo-Nazi PMC, was formed in St. Petersburg in 2014 under the official title: Sabotage and Assault Reconnaissance Group Rusich. Rusich proffers services in sabotage and reconnaissance operations. The founders, Alexei Milchakov and Yan Petrovsky formed Rusich after graduating from the Partizan paramilitary training program run through the Russian Imperial Legion in the summer of 2014. The organization regularly uses the Kolovrat and the Valknut as emblems.

In 2014 Rusich launched its first operation by attaching itself to General Alexsandr Bednov’s Batman battalion in support of Russian separatists in Eastern Ukraine during the Crimean War. Nationalist members joined from St. Petersburg, Moscow, and other cities of the ‘Rus’. The group quickly gained notoriety for their unrestrained brutality and Neo-Nazi ideology. While in the Luhansk oblast, Rusich carried out sabotage missions. While in the Donetsk oblast, the group battled near Belokamenka and Novolaspa. As Vice Commander, Petrovsky took part in the battles for the Lugansk and Donetsk airports. By the end of June 2015, Rusich had officially pulled out of Ukraine. Several Rusich members, including Milchakov, then joined the Wagner Group on operations in Syria.

Rusich maintains close ties with Wagner, as they are known to operate as a Wagner subsidiary. The two groups fought alongside one another in the Luhansk oblast from 2014-2015 and, more recently, in Palmyra, Syria. Wagner’s commander, Dmitry Utkin, even bears SS epaulets along his collarbone, further indicating the group's common ideology. From at least 2016 onward, members of Rusich have been involved in operations with Wagner near Palmyra, Syria. The main task has been to protect state-owned and Russian-financed oil and gas infrastructure from ISIL. About 80 percent of Syria’s gas production capabilities are located at the Al-Shaer facility in the Homs-Palmyra region.

Task Force Rusich also maintains a constellation of connections with the VDV airborne paratrooper units of the Russian military, the Russian Imperial Movement (RIM), and the Union of Donbas Volunteers (SDD). Rusich is known to train at the same facility as the RIM. The organization amplifies its ideology and actions to a sizable audience across multiple platforms: Telegram, Instagram, Twitter, and VKontakte, allowing them to reach international members in Poland and Italy. Frequent social media crowdfunding efforts to raise funds for equipment and medicine indicate the organization is largely unsupported by Russian logistical operations. Rusich members, including Milchakov and Petrovsky, have been known to post violent videos and images depicting the mutilation of killed Ukrainians. Task Force Rusich has been officially sanctioned by the United States Department of the Treasury for participating in the War on Ukraine. The European Union, Australia, Canada, and Switzerland have also imposed sanctions.

On September 27, 2021, the official Rusich Instagram account posted its members conducting military training exercises on top of an infantry fighting vehicle. One month later, on October 28, Rusich indicated that the Task Force had plans to return to the Eastern Ukrainian city of Kharkiv. Task Force Russisch has been operating in Ukraine since at least before the invasion in February 2022 (see the following table), as seen in the following images. TFR published these images on their now-down Instagram, illustrating that there were TFR members in the now-separatist recognized regions of Donetsk and Luskahnk.

In April 2022, identified members began posting their images in the area on their official Instagram webpage. Some, however, argue that the group has been operating earlier than April, as snow is depicted in some members' photos (see the following table).

On May 27, Dannil Bezsonov, a spokesman for Russian-backed separatists in the Donetsk region, posted a photo confirming Milchakov and Petrovsky were in Ukraine.

On September 22, Rusich posted detailed torture techniques and body disposal advice to be used on captured Ukranians. In December, the organization began urging Telegram followers to collect and share intelligence on border activities and military movements in Latvia, Lithuania, and Estonia. Information on communication towers and coordinates of fuel depots and security systems were similarly requested.

PMC MAR

MAR is registered as a PMC in St. Petersburg, Russia. According to its website, the company’s activities aim “to gain profit from private military services” and “the protection of the Russian-speaking population in the territory of neighboring countries”. Company founder Oleksii Marushchenko boasts the PMC participated in the events of annexing the Crimean peninsula. Ukraine’s Ministry of Defense reported that Russian PMC MAR participated in the 2020 Eastern Ukraine “logistical auxiliary support operations, primarily cargo delivery, including munitions and military equipment”.

Patriot

The Russian PMC, Patriot, was first discovered in Syria, conducting long-range reconnaissance in the Spring of 2018. The organization is affiliated with one of Russia’s top officials; Sergei Shoigu, the Minister of Defense. This organization also maintains close ties with Russia’s military intelligence agency, the GRU. Unlike the Wagner Group, Patriot attempts to maintain a high level of obscurity and, therefore, has no official contact or social media page. Membership comprises military professionals and lawyers serving in GRU Special Operations Forces or the Main Directorate of the General Staff of the Armed Forces. The acquisition of members has been effectively leveraged through the enticement of salaries ranging from $6,100 - $15, 200/month, with contracts typically lasting 1-2 months. Competitive pay, attributed to a member's high level of competence, has resulted in better training and equipment, further fueling the recruitment demand.

Patriot is known for providing protection services for statesmen and high-profile individuals, while further supporting Russia’s interest in expanding its sphere of influence in Africa and the Middle East. While attempting to secure a contract in the Central Republic of Africa protecting gold mines, pre-existing tensions between Patriot and Wagner were exacerbated, as the former was able to secure the lucrative arrangement. This tension remains high as Prighozin continues to insist Shoigu must be held responsible for military failures in Ukraine. The rift between Prighozin and Shoigu will likely play out on the battlefield with Wagner versus Patriot, as many consider the two to be competitors. A spokesman for the Eastern Grouping of the Ukrainian Armed Forces, Serhiy Cherevaty, maintains Wagner and Patriot operate in separate theatres with no direct interaction. Patriot was first spotted in Ukraine on December 28, 2022, near Vuhledar in the Donetsk Oblast. This recent deployment of Patriot illustrates a noticeable shift in dependency from the convict-ridden Wagner PMC to Shoigu’s top-qualified units, further underscoring Russia’s commitment to winning.

3. Ukrainian PMCs and the International Foreign Legion

Can we speak about PMCs in Ukraine?

Since the start of the war in February, the Ukrainian government has been openly calling international fighters to join Ukrainian forces, even lifting visas after the start of the war and simplifying the provision of Ukrainian nationality to volunteers as early as 2019. Since recruiting and joining PMCs is prohibited under Ukrainian law, the following discussion will center on the activities of “foreign fighters” or “volunteers” partaking in the conflict. While similarly, both volunteer fighters and mercenaries often have foreign nationality and complicate the conflict through illicit activities, there are essentially ideological, and footing differences between foreign fighters, foreign legionnaires, PMCs, and mercenaries.

Foreign fighters' primary motivations are ideological, with most joining for either religious, ethical, or political affinities with the respective combating side, while PMCs’ and mercenaries’ primary motivations are private gain, however, this distinction can be blurry in practice. More importantly, mercenaries lack combatant status compared to fighters, with legal consequences for their participation status in the conflict and status when imprisoned. The distinction between foreign fighters and legionnaires is less legally embedded, as legionnaires often fight with rebels and militias rather than joining recognized national militaries.

According to the Ukrainian government, units of international fighters formally fall under Ukraine’s regular armed forces and report to Ukrainian commanders. Observing Ukrainian Armed forces structures, both national military personnel and a broad spectrum of adjacent volunteer militia groups, makes it hard to distinguish foreign fighters from foreign legionnaires. As aforementioned in previous sections, Russia announced it would consider any foreigners fighting for Ukraine to be mercenaries. This has significant consequences for their recognition as a combatant and, if captured, prisoner of war (POW) status. Under International Humanitarian Law, volunteers joining the Ukrainian Armed Forces directly and volunteer battalions that are incorporated into the Ukrainian Army should fall under POW status. However, according to Russian officials, if captured, they would not be entitled to POW status.

While the involvement of PMC-like structures on the Russian side of the conflict is more easily detectable, observing PMC-like structures on the side of Ukraine, despite limited evidence for their existence starting around 2011-2013, is made challenging in the face of the official ban on PMCs under Ukrainian Law and due to unclear division between Ukrainian Armed Forces, hired voluntary military groups, and mercenary actors. In particular, there are blurred lines between combatants fighting for Armed Force battalions and identity militias or legions, identity militias, and unofficial or unnamed groups. Among these militia and legionnaire groups recognized by the Ukrainian Armed Forces, there are post-Soviet (notably the Belarusian Kalinovsky and Pahonia regiments and the Georgian National Legion, among others), Russian and Chechen deserter volunteer groups, but fighters from these countries sometimes also join existing battalions individually. The informal status of groups and the mixture of Ukrainian and foreign soldiers in certain army structures makes it further unclear to which extent the foreign volunteers, most of which entered through the International Legion of Defence of Ukraine, also known as Ukraine’s foreign legion, are considered part of the armed forces or not.

The International Legion of Territorial Defence of Ukraine (ILDU)

The International Legion of Defence of Ukraine is a military unit fighting with the Ukraine Armed Forces. It consists of foreign volunteers from at least 90 countries, selectively recruited on a contract basis formally until the end of martial law. It is the biggest unit recruiting foreign volunteer fighters into the Ukrainian troops, and its function is primarily to support Ukrainian Army units in practice, on the front line. Most of its combatants are ex-military personnel from nearby post-Communist countries, but Western state soldiers are also notably present. Some register with the Ukrainian Legion directly through Ukrainian Embassies, and others – mostly highly skilled Western Army veterans – join contractually through private recruitment via Silent Professionals, a widespread source of private military contractor job offerings. The latter arguably occupy a grey area between mercenaries and foreign fighters. The mixed recruitment sources of soldiers result in some foreign fighters being paid from the Ukrainian national defense budget, while contracted professionals are privately funded.

Despite its undeniable role in several military successes, the Ukrainian Legion’s ambiguities regarding its combatants’ activities and legal status have been criticized. The Legion has been met with accusations of leadership misconduct regarding the ethics of their operations and the treatment of their combatants, sometimes deploying them unprepared or in understaffed units. Even though the combatants undergo a vetting and selection process before being granted admission to the legion, several instances have been reported in which little to no training or prior information was conducted before combatants were sent into missions. As combatants are expected to bring their military kits into the mission, this often results in disparities between available materials and a lack of supplies during missions. The lack and miscoordination of supplies also seem to be due to internal corruption and robbery. Within and between fighting units, reports have cited commanders stealing military equipment from their soldiers. Near the end of January 2023, as part of a more considerable corruption exposure in Ukrainian national institutions, several Defence Ministry officials have also been accused of fund embezzlement schemes, notably buying military food at inflated prices.

The leadership within the Defence Ministry’s Directorate for Intelligence (‘GUR’), to which all army commanders report and under which fall the Ukrainian and International special forces units – Special Unit of International Legion, the Czech Aerozovedka Group and the Special Combat Team Spook –, has particularly been criticized for their conduct, in large part through complaints by the foreign soldiers following the commands of the Directorate heads by extension. Four people largely decide the division’s instructions for the Foreign Legion: major Popyk, major Vashuk, and his uncle, and intelligence officer Kuchynsky. These higher-ups are mainly criticized as being responsible for instructing commanders with decisions that endanger the Legion’s soldiers or force them to partake in unethical activities. Based on a report and interviews with Legion members, certain commanders further instructed and pressured Legion soldiers into looting, assaulting, and sexual harassment of female medical personnel, alongside joining ‘suicide’ missions with little preparation. Moreover, one of the commanders allegedly has ties with a Polish criminal group and is persecuted for fraud in his home country. Being forced into misconduct is an ethical loss for the activities of the legion, and forms a problem for foreign fighters who risk breaking their home country’s laws in following the instruction of their commanders.

Alongside leadership accountability problems and in line with the largely non-formalized incorporation of foreign military personnel into the Ukrainian army, the Legion suffers from a lack of clear organization. Structure-wise, most of the Ukrainian Legion’s units consist of foreign soldiers exclusively for logistic purposes and to avoid language barriers in communication. However, some work closely with Ukrainian soldiers or contain Ukrainians of other nationalities who previously fought for other nations. This is further complicated by the Legion having units formed by Russians formerly fighting for the Russian side, as well as Belarusian and Chechen units opposing Russia, the vetting of which, before being granted admission into the Ukrainian Armed Forces, does take place but is largely unclear.

Overall, these leadership defaults and inefficient preparation of troops highlight the problems in coordination between the Ukrainian troops and the foreign volunteers, as well as the diminishing will of the foreign volunteers to continue fighting under the conditions they are met with. A large part of the 20 000 foreign recruits counted by the Ukrainian government in Spring 2022 has reportedly returned to their home countries over the summer. Furthermore, by tarnishing the name, the corruption allegations have a detrimental effect on the reputation of the Legion as a viable unit to fight for new foreign volunteers.

Stationing of Ukrainian (blue) and Russian (red) troops, alongside a list of volunteer groups and legions, categorised in the map as part of the Ukrainian Armed Forces. (Source: The Project OWL OSINT).

4. United States PMCs

The United States’ motivation to use PMCs

The US is the biggest consumer of PMCs services and has been that for decades. There was a drastic increase in the use of PMCs after 9/11 and the war on terror and the use of private military contractors in Iraq and Afghanistan. There is a deliberate choice behind the US privatisation and outsourcing of what used to be done by military forces. The US decreased the size of the standing army after the Cold War; nonetheless, the goals and objectives remained the same. The US grand strategy of being the guarantor of global stability was challenging to maintain with a lack of resources. The solution was private contractors contributing to filling the gap between geopolitical goals and public means.

PMCs are seen as a promising alternative because of their supposed low cost and efficiency. The Montreux conventions constrain the main task done by western PMCs, and usually, PMCs solve defensive tasks such as “armed guarding and protection of persons and objects such as convoys, buildings, and other places, maintenance and operation of weapons”. The use of PMCs also shifts the responsibility from the state and contributes to lower visibility of operations; this is seen as beneficial for the US. For example, there had been a proliferation in using PMCs in Afghanistan as a replacement for retracting American troops. Employing PMCs instead of regular troops is a way of maintaining a US presence and avoiding the often-unpopular move of stationing regular American soldiers in conflicts around the world.

We have observed the presence of western PMCs working inside Ukraine, and western PMCs have seen increased demand for their services in the conflict. A likely next step in supporting Ukraine for the US and its allies may be to contribute with private contractors. This has several benefits from the US point of view. First, this will support the US grand strategy of being the world hegemon without deploying American troops, which would be costly and may be viewed as an unpopular move. Furthermore, PMCs will also decrease the responsibility the US has in the conflict; it can be a way of contributing subtly and under the radar without escalating the conflict.

Blackwater/Academi

Former Navy SEAL Erik Prince, the founder of Blackwater (now called Academi) had been operating in Ukraine before the Russian invasion. In June 2020, Prince visited Kyiv to discuss a venture that would give Academi a pivotal role in the Ukraine military industry. “Windward Capital, an investment vehicle that Prince had used in the past”, sought to purchase 76% of a Ukrainian factory for $950 million to manufacture weapons and create a private military in Ukraine. In addition, Prince visited Kyiv in February 2022, following the Russian military build-up, and obtained a “gentleman’s promise” that he and his associates would not be held legally liable for their work in the Ukraine war. Despite Academi's involvement in Ukraine being unclear, Prince’s meetings with security officials of Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky’s regime demonstrate that Academi has played an active role in the conflict, with their presence complementarity between training Ukraine’s military and logistical support.

The Mozart Group

The Mozart Group (TMG) was formed in March 2022 by Andrew Milburn, who retired from the Marine Corps as the Deputy Commander of Special Operations Command Central, responsible for all US special operations in the Middle East. TMG is estimated to have about 50 – 60 people in Ukraine, most former military of British, American, and Ukrainian volunteers. The group offers several types of services including: training military defence units in survival skills, military-level planning, and execution of operations to recover vulnerable populations, and training medics and other medical personnel. Between March and August 2022, the group reportedly trained 3,000 Ukrainian soldiers in centres located near combat zones, in the “Donbas, as well as, in Odessa and Zaporizhia”. It has also been reported that in June 2022, 10,000 Ukrainian soldiers underwent military training in the UK on handling anti-tank systems.

TMG is a member of the U.S. – Ukraine Business Council. In April 2022 reported that 62% of international humanitarian aid arriving in Western Ukraine does not continue on the front line where it is needed. TMG assists in logistics, delivering humanitarian aid, and military equipment, which would be blocked at the country's borders, causing supply chain difficulties for international NGOs and humanitarian agencies.

TMG also provides intelligence gathering through “fact sheets” to governments and non-governmental organisations, which are a collection of field intelligence and OSINT handed over to the Ukrainian special forces so that they can target Russian military forces on the ground. The Mozart Group stands out from other SMPs through its communications on social media and traditional media, openly promoting its involvement in Ukraine and exposing distressing images of the front line of the war.

The purpose is to highlight the TMG actions and obtain private donations. As such, TMG is integrated into defending American interests in Ukraine and allows the US to support the Ukrainian military without being directly involved. Its digital-savvy actions allow it to gain media attention, but it should not obscure the activities of other American PMCs operating in the war in Ukraine.

5. Conclusions

This report has explored in a two-fold manner the legality and status of the actors involved in the Ukraine-Russia war, their involvement, and the latest updates. We conclude that, even though social media platforms and traditional media have widely used the term mercenaries and their involvement in the war to refer to the involvement of the Wagner Group, US groups, like the Mozart Group or Academi, it is exceptionally complicated to frame them as such. Because of the narrow legal definition of what a mercenary is according to the Protocol Additional to the Geneva Conventions, we cannot state and assess with a high degree the unlikelihood that there are mercenaries in Ukraine. In this line, PMCs operating in the conflict will likely be profiting financially from it and could fulfill several aspects of the definition. However, they do not fall under the category of mercenaries. Therefore, we cannot refer to them as such.

By assessing Russia's, Ukraine's, and the United States's motivation for employing non-traditional military forces in the war, we could understand which role they are performing and in which way they could be involved. On the one hand, Russia and the United States employ private military contractors, but their motivation differs slightly. On the other hand, both use PMCs as part of their modern asymmetrical warfare tactics to pursue their geopolitical goals. However, Russia uses them especially to complement the work of their military forces involved in the conflict. Whereas the US is not directly and officially involved in using PMCs to advance their geopolitical goals and support Ukraine, the Russian government utilizes them due to their low cost, efficiency, professionalization, and as a possibility to deny their involvement. As far as Ukraine is concerned, due to the lack of legalization of PMCs, they are relying on international volunteers under the direction of the Ukrainian military forces.

The OSINT and SOCMINT investigations we have conducted led us to find:

Russia’s incredible reliance on PMCs, differing their importance between this conflict and other conflicts where Russia actively relies on PMCs, like the Wagner Group. Whereas the Wagner Group plays a predominant role in advancing Russia’s objectives in the Ukraine-Russia war, the role of Task Force Rusich and Patriot, have been complementary and necessary to fulfill that task.

Compared to Russian PMCs like Wagner or Patriot, Task Force Rusich has been increasingly public on their involvement in the war, making our SOCMINT investigation to be more successful and, therefore, including more visuals about their participation.

The United States PMCs, like Academi and the Mozart Group, defend American interests abroad but have done it by aiding the Ukrainian military in training and intelligence gathering, resulting in plausible deniability the US can publicly make if asked about their involvement in the conflict.