Water Scarcity in Africa: A Changing Landscape of Challenges and Opportunities

The right to water, as recognized by the United Nations, entitles all individuals to access to sufficient, safe, physically accessible, and affordable water. However, this right is not reflected in practice. The African continent has suffered from a water scarcity crisis for decades. Its implications on communities’ food, health, and economic security have been critical and have not been effectively mitigated by governments or international humanitarian actors. There is an urgent need for improved infrastructure and governance, enhanced international cooperation, and greater awareness about the effects of water scarcity to tackle the crisis in Africa and ensure that all individuals are provided with enough clean water to meet at least their basic needs.

Drivers and Recent Trends

Water scarcity in Africa has developed into a complex emergency. Changing climate patterns, a rapidly growing population, inadequate infrastructure, and poor governance have contributed to a critical water crisis that threatens both the health of the African population and the stability and development of the entire region.

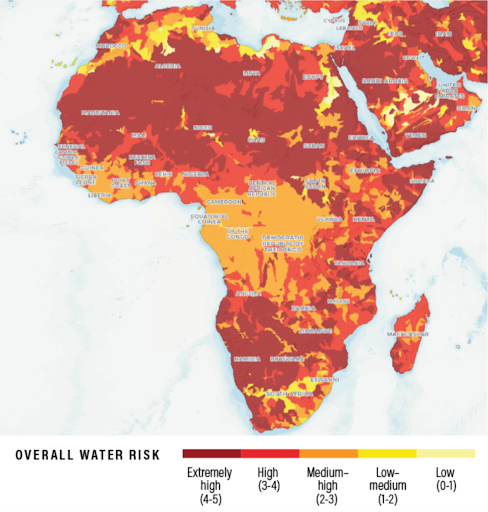

Of the 23 countries worldwide labelled as ‘critically water-insecure’ by the UN Institute for Water, Environment and Health, 13 are located in Africa. These countries are characterised by low levels of access to safe drinking water, sanitation services, and water resource stability. Africa has the lowest levels of safe water access of any continent; in 2020, only 15 per cent of the continent had access to safe drinking water. In Chad, nearly 50 per cent of the population consumes drinking water with very high levels of E. coli, while just 6 per cent has access to safely managed potable water.

Over the past five decades, despite advancements in access to safe water and sanitation around the world, since 2020 Sub-Saharan Africa has witnessed an increase in the proportion of its population lacking access to secure potable water services. An estimated 70 per cent of people in Sub-Saharan Africa lack safe drinking water services.

Source: Naddaf 2023

Several mutually-reinforcing factors are contributing to Africa’s water scarcity crisis. First, the continent’s climate, characterised by high temperatures, variable rainfall, and harsh aridity, has contributed to both desertification and intense flooding. While Africa has the highest number of countries at high risk of droughts, there remains a severe threat of flooding, as evidenced in Somalia and Ethiopia earlier this year.

Second, Africa’s rapid population growth is increasing the demand for water resources. Sub-Saharan Africa’s population is growing at 2.7 per cent annually, which is more than twice as fast as South Asia (1.2 per cent) and Latin America (0.9 per cent). This is placing immense pressure on the continent’s water and food resources, especially as these are gradually being depleted by (largely human-induced) forces such as climate change.

Third, government policies have been unable to slow these trends. Distinguishing between physical and economic water scarcity is fundamental to understanding the implications of water scarcity and devising appropriate responses. Physical scarcity refers to the condition wherein available water resources fall short of fulfilling the needs and demands of the population. On the other hand, economic water scarcity arises where, despite the natural availability of water, access to water is limited due to a lack of infrastructure, high costs, and institutional constraints – in other words, due to poor policies and governance.

Arid regions of the continent, mainly located in North Africa, are characterised by physical water scarcity, whereas Sub-Saharan Africa predominantly experiences economic water scarcity. Interestingly, water stressed countries, particularly Algeria, Libya, and Egypt in the North, and Namibia, South Africa, and Botswana in the South, make water available to a higher proportion of people than in countries with abundant water resources, like the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC). The DRC possesses over half of Africa’s water reserves and receives frequent rain, yet lacks the infrastructure and regulations to provide millions of Congolese with access to clean water. Even within countries, economic water scarcity impacts individuals differently, as it acts upon existing socio-economic inequalities dictated by income, gender, race, level of education, or political beliefs. These statistics highlight the role of government policy in ensuring an equitable distribution and supply of safe water for citizens.

Economic water insecurity is often derived from poor regulatory mechanisms governing the use of bodies of water. The pollution and contamination of water have become critical issues, stemming at least in part from the mismanagement of agricultural, animal, and industrial waste, as well as the overexploitation of bodies of water, as in South Africa. As a result, contaminated water is often utilised in households, particularly in settings where alternative water sources are unavailable.

Fourth, private companies and organisations have attempted to profit from Africa’s limited public water access by privatising water. This has rendered water an increasingly elusive resource by making it more expensive and inaccessible. In areas worst hit by droughts, in the Horn of Africa for example, the cost of water has increased by up to 400 per cent, leaving many without enough water to meet basic needs. Water privatisation has thereby widened inequalities, while also potentially creating opportunities for corruption. In Uganda, “private contractors estimated the average bribe related to a contract award to be 10 percent (of the total cost),” meanwhile an estimated 46 per cent of urban water consumers pay extra money to connect their households to a water network. Corruption ultimately inflates water prices, thus denying poorer segments of the population access to water.

Fifth, climate change is further complicating matters. The Horn of Africa region, for example, is in its fourth consecutive year of drought and is experiencing the impacts of “one of the worst climate-induced emergencies of the past 40 years.” The region’s minimal rainfall has triggered a water scarcity crisis, with more than 8.5 million people, almost half of them children, facing dire water shortages. This represents merely one instance amid a multitude of cases across the continent.

The Implications of Water Scarcity

The water scarcity crisis in Africa has, and will continue to have, important consequences at the local, regional, and international level. Not only does it critically impact human security, but is also intensifying migration flows and exacerbating conflicts, thereby requiring regional and international bodies to step up their operations to respond to growing humanitarian emergencies.

First, water scarcity has a prejudicious effect on the continent’s human security. The lack of safe, accessible drinking water increases the likelihood of chronic dehydration, particularly in areas with arid climates. Water scarcity also compromises food security and livelihoods. A large proportion of the African population is reliant on agriculture, farming, and fishing for both personal consumption and as a source of income. The inconsistent access to and supply of water reduces crop yields and the availability of food, exposing communities to critical socio-economic and health vulnerabilities. Moreover, water scarcity contributes to environmental degradation; parts of Africa have witnessed increasing desertification and a loss of biodiversity, which compounds existing challenges to livelihoods. For example, over one-third of Burkina Faso’s farmland is degraded as a result of both prolonged periods of drought and improper land use, thus gravely impacting the population’s food and economic security.

From a macro-level perspective, water scarcity can also slow economic growth. Inconsistent agricultural yields and industrial productivity that contribute to persistent poverty and famines, make water insecurity a critical impediment to economic development. Simultaneously, limited food outputs can induce inflation and thus impact both national and global food prices.

Water scarcity also significantly increases the likelihood and spread of diseases, such as cholera and diarrhoea. An estimated 842,000 people die from diarrhoea every year as a result of unsafe drinking water, sanitation, and hygiene. Access to hand-washing facilities ranges from 25 per cent of the population in Chad, to just 9 per cent in Burkina Faso. In regions characterised by water scarcity, communities are less inclined to allocate water resources to hygiene-related activities, thereby augmenting the probability of disease proliferation and transmission.

Source: Our World in Data 2019

Water scarcity’s impact on human, health, and economic security inherently reinforces inequalities. While communities living in rural areas, informal settlements, or low-income settings often struggle to meet their basic water needs, individuals in comparatively advantageous socio-economic positions are able to access privatised sources of water. Water scarcity disproportionately impacts the most vulnerable people, including children who are at a greater risk of developing conditions stemming from malnutrition, such as stunting and diabetes. Water insecurity may also exacerbate gender inequalities; when water is not easily accessible, the burden of travelling to collect it often falls on women and girls. This represents a “high opportunity cost to obtaining education or employment.”

Second, water scarcity is a driving factor for migration. Internal displacement in African countries has significantly increased in recent years due to persistent conflict, resource scarcity, and natural disasters. In Burkina Faso, the number of internally displaced persons (IDPs) grew from less than 50,000 in October 2019 to around 2 million in March 2023. Inherently, migration hinders the ability to secure stable and reliable access to water resources. Rural-urban migration, towards Nairobi and Mombasa for instance, has led to overcrowding in cities not equipped to deal with overpopulation, placing huge strains on water resources, further intensifying water scarcity. Water insecurity has also driven transborder migration, increasing the demand for, and pressure on, water resources in neighbouring countries. The almost-total disappearance of Lake Chad, a vital source of water and livelihoods for 30 million people in the Sahel, has forced the displacement of three million people and has left 11 million people in need of humanitarian assistance. The combination of resource shortages, forced migration, and pre-existing tensions has served to trigger violence between fishing, farming, and herding communities.

Third, water insecurity has contributed to the provocation of conflict on the African continent, both within and across borders. Violent clashes have, in turn, exacerbated human security and triggered further migration and conflict. Beyond Lake Chad, tensions have emerged between Egypt, Sudan, and Ethiopia over access to the Nile Basin, especially after the latter began the construction of a hydroelectric dam that Egypt claims could drastically reduce water flows into the country. Moreover, the potential for, and fears of, transboundary conflict have triggered intra-state discontent. For example, the development of the ‘Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam’ heightened the Egyptian public’s concerns about reliable water access and generated significant pressure on the government to respond firmly. Furthermore, human dependence on water has been intentionally exploited during conflicts; water resources, systems, and infrastructure required to deliver water have come under direct attack. In fact, children under the age of 5 living in conflict zones are 20 times more likely to die from diseases linked to unsafe water and sanitation than from direct violence.

Fourth, on a more global scale, the combination of famines, droughts, diseases, migratory flows, and armed conflicts resulting from water scarcity in Africa have generated an urgent demand for international humanitarian interventions. The international community is confronted with growing expectations regarding the coordination of increasing volumes of aid to help African governments mitigate the local impacts of water stress. Additionally, international actors must overcome barriers to the access of remote or crisis-affected settings to ensure the timely delivery of essential water resources and facilitate the development of vital infrastructure. The international community finds itself at a critical juncture as current efforts to address the unfolding water scarcity crisis hold the potential to shape long-term trajectories and trends.

Looking Ahead: Challenges and Opportunities

Evidently, the water scarcity crisis entails significant risks and challenges for African governments and the international community in years to come. Current trends indicate that water scarcity, as well as its consequences for human security (including famines, poverty, inequality, health insecurity, migration, and conflict) are likely to worsen. Both climate change and Africa’s rapid population growth will place increasing pressure on the continent’s water resources, while central governments may lack not only the capacity, but also the political will, to respond adequately. Guaranteeing equitable access to safe, clean, and sufficient water to meet individual basic needs, both personal and economic - and thus preventing the onset of large-scale humanitarian crises - will represent a critical governance challenge in coming years. Measures must be taken to improve national water management, storage, distribution, and recycling capacities, especially through infrastructure expansion. Governments will have to recentre their efforts towards preventing and managing water scarcity, instead of merely attempting to deal with its consequences.

At the same time, the unfolding challenges linked to water scarcity in Africa present important opportunities for both governments and the international community. First, huge potential exists for states to invest in and develop durable infrastructure to ensure the reliable supply of clean water to homes. This specifically includes piped water systems, which can help provide communities with readily available drinking water, while removing the need for women and children to travel long distances and forgo education or work. This would inevitably increase children’s school attendance and free up time for women to engage in more productive activities, which would have positive implications for countries’ economic growth.

Simultaneously, governments should invest in the development and distribution of sustainable, water-efficient, climate-resilient practices and technology, such as drip irrigation, reforestation, and the extraction and recycling of groundwater, to sustain livelihoods and mitigate physical water scarcity in the long term. Thus far, “water resources harnessed and land area developed for irrigation in Africa are still far below the (region’s) potential,” opening up an opportunity to fill this gap. The digitisation of agriculture and farming would significantly help conserve water resources and render activities more productive and efficient, thus contributing to communities’ food, health, and economic security. Some African countries have already taken important steps in this regard: Namibia has improved urban wastewater management in Windhoek, recycling sewage water into drinking water, meanwhile the Kenyan government has sought to increase the distribution of drought-tolerant maize varieties.

Equally important is the need for improved data collection; governments must cooperate with sub-national actors to expand the available data on both physical and economic water scarcity, to ensure that implemented projects yield desired results and are endorsed by recipient communities. All the above efforts can be pursued jointly by national governments, the private sector, and the international community.

Relatedly, the water scarcity crisis presents an important opportunity to enhance cooperation on water management at the regional and international level, whether through development institutions, regional bodies, or inter-state frameworks. Currently, multilateral efforts to combat climate change and reverse water scarcity trends in Africa are insufficient. There is still no global framework for addressing water stress, like there is for climate change and the preservation of biodiversity. Water insecurity must be prioritised on international and regional agendas. State and non-state actors alike should increase their support to African governments, through capacity-building programmes, disbursements of financial assistance, exchanges of technical expertise, and infrastructure development.

The United States’ Partnership for Global Infrastructure and Investment (PGII), developed in 2022, represents a good starting point, as it seeks to mobilise private capital investment towards infrastructure linked to climate and energy security, digital connectivity, health security, and gender equality. Such goals could support important investments in water infrastructure. Yet this initiative does not go far enough to prioritise the issue of water scarcity and forefront the urgent need for improvements to water management policy and infrastructure in Africa.

Source: Our World in Data 2021

Meanwhile, within Africa, the African Risk Capacity (ARC) Group, as part of the African Union, has been playing an important role in tackling water scarcity. Its sovereign insurance mechanism has paid out over $36 million to African countries affected by drought since 2014, preventing further famines, poverty, and health insecurity. However, this framework has mainly focused on assisting countries to respond to the effects of water scarcity, rather than encouraging the development of infrastructure and technology that can mitigate and prevent these effects in the first place. Despite providing important assistance in times of crisis, more needs to be done to ensure that all individuals across Africa obtain reliable access to safe, clean, and readily available water before having to suffer the impacts of water scarcity.

Lastly, there is a crucial opportunity to enhance education and raise awareness about water scarcity and its effects, particularly on human health. Governments must invest in initiatives aimed at encouraging behavioural changes, particularly where water scarcity is less pronounced, and promoting climate-resilient agricultural practices. Central governments must simultaneously support bottom-up, micro-level initiatives seeking to tackle both the causes and effects of water insecurity. Only through a combination of local, regional, national, and international efforts can the current water scarcity crisis be mitigated and communities across Africa be provided with long-term access to clean, safe, and affordable water.