The Risks Presented by Poverty, Inequality and Unemployment in South Africa

Executive Summary

London Politica assesses with high confidence that increased poverty, unemployment, and inequality levels will likely continue to drive crime, unrest, and the rise of populist parties in South Africa. This will likely negatively impact the perceived legitimacy and support of the Government of National Unity (GNU) coalition.

To address these challenges effectively and maintain popular support, we assess that the GNU would benefit from investments in infrastructure targeting electricity and water supply, as well as social programs, education and poverty alleviation initiatives at the local level. The implementation of structural macroeconomic reforms to improve living standards and public sector efficiency would also likely continue to improve the country’s business climate and attract foreign investment.

Declining unemployment rates are expected to strengthen demand-driven growth, as evidenced by the 1.3% increase in household consumption following the election. This will likely reinforce business confidence and accelerate the expansion of key national industries, including mining, construction, manufacturing and electricity.

Despite growth in key domestic sectors, economic activity declined across government consumption, imports and exports, contracting GDP by 0.3% in Q3. Persistent trade weakness, driven by declining imports of minerals, precious metals and machinery will likely further constrain trade flows in the near term, limiting the GNU’s external growth prospects.

Introduction

South Africa remains one of Africa’s most advanced and diversified economies offering a relatively stable investment environment. Its appeal to foreign investment lies in its world-class financial services, deep capital markets, transparent legal framework and abundant natural resources. Key sectors attracting foreign direct investment (FDI) include manufacturing, mining and financial services. Despite ample investment opportunities, FDI inflows have consistently declined since 2022, dropping from $1.3 billion in the first quarter of 2024 to $965.87 million in the second quarter.

Throughout 2024, South Africa’s economy faced significant disruptions due to persistent electricity shortages, civil unrest and logistical challenges. These factors - coupled with the outcome of national and provincial elections - substantially impacted business confidence, as the South African Chamber of Commerce’s Business Confidence Index (SACCI) declined by 6.9 points over the two months following the May 2024 general election.

The 2024 general elections marked a historic shift in South Africa’s political landscape, as the African National Congress (ANC) lost its 30-year parliamentary majority, securing a record low of 159 seats. This led to the formation of a coalition government, the Government of National Unity (GNU), composed of 10 parties collectively holding 287 of 400 seats (72%) in the National Assembly. The Democratic Alliance (DA), a pro-business party and the main opposition to the ANC, emerged as a key coalition member, securing 87 seats in the National Assembly.

By prioritizing economic growth and a stable business climate, the GNU has gradually bolstered business confidence through its commitment to implement structural economic reforms and enhance public sector performance. The joint initiative between the presidency and the National Treasury dubbed “Operation Vulindlela” aims to transform electricity, water, transport and digital communication infrastructure to promote economic growth and attract foreign investment.

Within six months of the general election, economic growth and investor confidence are gaining momentum, driven by anticipated structural economic adjustments in energy, logistics and the public sector. The South African Reserve Bank reported the first net inflow of capital since 2022, shifting from an outflow of $1.1 billion in Q2 of 2024 to an inflow of $2.1 billion in Q3. This shift reflects renewed investor confidence in the country’s economic stability, as evidenced by increased inflows of direct investments, portfolio investments and reserve assets.

While the business climate shows signs of improvement, the GNU is likely to face multifaceted risks associated with unemployment, poverty and inequality. South Africa’s high unemployment rates - particularly among young people - create profound negative externalities for the state, as the country’s demographic dividend is disproportionately wasted due to a lack of investment in human capital development. Although 22,000 jobs were created in 2024, 137,000 South Africans entered the workforce the same year. The expanded unemployment rate (including discouraged seekers) was 60.8% amongst 15-24 year olds in Q2 of 2024. As unskilled and unemployed working-age adults are consistently delinked from the labour force, a long-term skill gap is latching itself into the employment market. This risks snowballing into a structural unemployment problem whereby individuals lack the skills necessary to bridge the gap toward average employment requirements.

Unrest

South Africa continues to grapple with worsening civil unrest; data illustrates a visible increase in registered protests and riots since 2021. Civil unrest poses significant risks to both the economic and security environment, leading to financial losses, disruption of business operations, and widespread property damage.

Unrest represents an operational hazard for foreign stakeholders and frequent business disruptions continue to damage the GNU’s legitimacy. These trends are likely to persist unless underlying economic issues are effectively addressed.

The July 2021 riots led to $1.5 billion in economic losses and two million jobs being lost or impacted for both local and foreign companies.

Our analysis of historical trends indicates that politicians' failure to appropriately address long-standing unemployment, inequality, and infrastructure deficits have driven grievances and unrest across the country.

Civil unrest remains a key issue obstructing social and economic development in South Africa. South Africa ranked 127 out of 163 on the Institute for Economics and Peace’s (IEP) Global Peace Index 2024, putting it amongst the fifteen most politically unstable countries in Sub-Saharan Africa. Civil unrest increased significantly last year, with 692 protests and riot incidents registered during the first quarter of 2023 compared to 456 over the same period in 2022.

Historically, analysts have associated civil unrest in South Africa with popular resentment towards high and stagnant levels of unemployment and inequality, which are amongst South Africa’s most critical and longstanding socioeconomic challenges. Unemployment increased from 21.8 percent to 28 percent between 2013 and 2023, with the World Bank describing it as “South Africa’s biggest contemporary challenge” in October 2023.

Moreover, South Africa has some of the highest income and wealth inequality levels globally. The population’s richest decile accounts for about 65 percent of national income while the poorest half accounts for 6 percent. Disillusionment towards politicians has historically grown amongst South Africans as governments fail to confront unemployment and inequality, particularly along racial lines.

In July 2021, former South African president Jacob Zuma was arrested in Estcourt, KwaZulu-Natal, after refusing to appear before a judicial commission investigating corruption during his decade in power. Zuma's incarceration led to the violent 'Free Zuma' protests, which escalated and spread to other areas of the country including major cities such as Johannesburg. The riots constituted the largest period of civil unrest since the end of the Apartheid, with an estimated 354 people losing their lives. In our analysis of related data and interviews conducted by local news sources, we assess these protests were largely driven by background economic grievances.

Although the riots in July 2021 were precipitated by Zuma’s arrest, enquiries conducted in the aftermath illustrate that the causes were more deep-rooted. The South African Human Rights Commission (SAHRC) found that high unemployment rates, inequality and poverty were the bedrock from which unrest permeated. Echoing the findings of the SAHRC’s investigation, South Africa’s Minister of Trade, Industry and Competition Ebrahim Patel stated that “while it was true that there were those with a different agenda who lit the match, that match was thrown on dry tinder in communities where there was severe unemployment and poverty”. Further, protests led by the trade union groups Congress of South African Trade Unions (COSATU) and the South African Federation of Trade Unions (SAFTU) over the cost of living and unemployment rates erupted in Pretoria and Cape Town in August 2022, and Johannesburg in July 2023. In late November 2024, residents clashed with police in Johannesburg over a lack of water supply, demonstrating risks of public dissatisfaction with infrastructure deficits.

Previous civil unrest in South Africa has driven security and economic implications that were detrimental enough to shift the risk perceptions of foreign investors and other overseas stakeholders. The ‘Free Zuma’ riots led to $1.5 billion in economic losses and two million jobs being lost or impacted at both local and foreign companies. Unrest primarily disrupts the transportation of goods as major road closures.

Protesters blockaded and damaged key sections of the N2 and N3 highways, significantly disrupting commercial traffic in the KwaZulu-Natal region (KZN) along routes critical to national and regional logistics networks. The closure of these strategic routes constrained commercial cargo traffic and transit freight, disrupting supply chains that link South Africa with landlocked African countries which resulted in significant shortages in food, fuel and medical supplies. In the aftermath, foreign investors cited these riots as a deterrent to new investments and the expansion of existing ones. The economic cost of violence in South Africa as a percentage of GDP amounted to 15.38 percent in 2023.

Assessment:

London Politica assesses that high unemployment and inequality are likely to stagnate or worsen without effective government investments in energy, telecommunication and water supply networks. The absence of effective social investments increases the risk of unrest, particularly in urban areas and neighbourhoods with higher poverty rates. Such unrest is likely to undermine the government’s legitimacy, as constrained economic growth and high unemployment erode support for the GNU’s coalition in favour of populist parties.

The GNU should enact structural reforms to address unemployment, infrastructure deficits, and public sector performance to prevent consequences associated with a declining investment climate. The government’s pledge to address supply-side challenges by boosting investments in electricity infrastructure will likely gradually improve economic productivity and foreign investment in the long term. Although enhanced electricity supply bolstered manufacturing outputs in 2024, persistent social unrest linked to infrastructure deficits remains deeply entrenched and is unlikely to be resolved in the short term.

We assess that disenfranchised South Africans are likely to turn to disruptive demonstrations to voice their grievances against the government’s lack of effective investment. Social unrest will likely continue over the GNU’s term, resulting in occasional infrastructure damage and substantial financial losses to cities and towns across the country.

Crime

South Africa faces high crime rates linked to socio-economic problems which are exacerbated by the ineffective use of resources. Crime and violence divert resources away from development programs, investments in infrastructure and crucial social services as the government focuses instead on immediate security measures.

This misallocation of resources fails to address the root causes of crime and contributes to social inequality. Important sectors like education and economic development are underfunded due to the focus on short-term security.

The problem is cyclical, with short-term security priorities hindering long-term development and prolonging instability.

Crime in South Africa has a very significant impact on foreign investment and capital inflows. Extortion, theft, and violent crime affect the legitimacy of the government and drastically complicate business operations in the country.

South Africa has one of the highest crime rates in the world and continues to see increases in violent crime, including crime that specifically targets businesses. New data put out by the government demonstrates that crime rates have increased since 2021 - coinciding with a decrease in government popularity throughout the same period. Compared to wealthy communities, crime rates in poorer neighbourhoods like Khayelitsha are nearly five times higher, which is indicative of country-wide trends. The significant economic and social issues that residents experience are linked to this disparity. According to research by the Institute for Security Studies, Khayelitsha's high unemployment rate, poor housing conditions, and restricted access to social services all lead to higher crime rates. These circumstances encourage grievances, which can lead people to commit crimes, as illustrated by strong empirical evidence linking economic hardship to higher crime rates in South Africa.

In addition to community-level crime, South Africa is plagued by transnational organised criminal networks that worsen the business environment, slow the economy, and threaten individuals' physical and financial security. According to the Organised Crime Index, South Africa ranks 3rd as the African country most affected by organized crime, based on the prevalence of criminal activity and the ineffectiveness of state responses to counteract it. Transnational organized crime is defined as illegal activities carried out across borders by structured networks such as gangs, drug trafficking syndicates and international criminal networks. The most prevalent criminal markets in South Africa are human trafficking, financial crimes and arms trafficking. Throughout 2024 the South African Police Service dismantled 30 illegal drug laboratories and seized over $18 million worth of illegal drugs.

The prevalence of organised crime is deeply rooted in corruption within government and police forces and is worsened by a lack of cooperation between institutions. Because a large number of politicians and bureaucrats benefit from corrupt relationships with criminal organizations, they hold a vested interest in impeding efforts to combat it. Government officials are frequently compensated to overlook illicit actions once they are uncovered and to provide details on police operations and strategies to combat criminal activities. Despite government strategies implemented to combat organised crime, a lack of institutional cooperation and corruption among government and police forces have hindered their efforts.

There are substantial geopolitical and economic implications of South Africa's internal instability and high crime rate. The country's failure to uphold internal security harms its standing as a regional and international leader, complicating its efforts to project influence and collaborate on international projects through its G20 presidency.

High crime rates - and high rates of extortion specifically - significantly discourage foreign investment; foreign investors have refrained from entering the South African market due to costs associated with crime, including security measures and insurance premiums. Furthermore, a World Bank study from 2023 on South Africa's investment climate notes that a decline in FDI has been observed in industries such as tourism and manufacturing due to safety concerns and high crime rates.

The South African government has attempted to implement several policies to lower crime rates. Crime reduction is a major goal of initiatives such as the National Development Plan (NDP) 2030. Strategies to achieve this goal focus on strengthening law enforcement, improving the justice system, and addressing the socioeconomic drivers of crime. These efforts are complemented by increased funding for the South African Police Service (SAPS) and the adoption of community policing techniques. Unfortunately, corruption, low funding, and the absence of institutional collaboration have frequently impeded these attempts. The overall influence on national crime levels has been minimal, notwithstanding localised successes in certain urban districts. A recent Gallup poll indicated that South Africa ranks among the top three countries in which people feel the least safe walking alone at night. This suggests that more comprehensive strategies are required that address the underlying socio-economic problems that drive crime, in addition to improving law enforcement capabilities.

Assessment:

We assess that insufficient investment in social development, coupled with the failure to address corruption linking the state to transnational criminal networks, is likely to exacerbate existing disparities between communities. This will likely place additional strain on the state’s resources, given the government’s inevitable investment in policing and short-term security expenditures. Rising crime rates driven by unrestrained poverty and inequality will likely fuel growing social unrest and continue to erode public trust in state institutions.

Pessimism concerning South Africa’s investment climate will likely continue to harm the government’s popularity and legitimacy. Limited economic growth worsens already-existing social inequalities, further inhibiting economic progress, and restricting the creation of new jobs. The risk of increasingly frequent and violent civil unrest will likely deter foreign companies from operating in the country, further restricting FDI flows and directly constraining economic growth.

We assess that heightened levels of social unrest are likely to compel the government to divert substantial resources toward security and reconstruction efforts, further constraining funding for investments targeting poverty, inequality, and unemployment. Effective investments targeting structural economic adjustments and socially focused projects will likely benefit the GNU’s expenditures in the long term.

Populism

Right and left-wing populism is on the rise in South Africa. The ANC dropped from a 70% vote share in 2004 to 40.2% in the 2024 general elections. In the same election, populist parties uMkhonto weSizwe (MK) and Economic Freedom Fighters (EFF) respectively gained 14.6% and 9.5% of the vote share.

The rise of populism in South Africa can in part be explained by high voter discontent for the longstanding ruling party, the ANC. Persistent economic challenges that disproportionately impact less educated and economically disadvantaged segments of the population are likely to continue to drive these groups to support populist parties.

Continued failure to address long-standing economic grievances by the government is likely to lead to the further delegitimization of the GNU, threatening its coalition and leading to increased support for populist parties.

Increases in support for populist parties can be particularly observed in rural areas, which have high levels of voter discontent due to regional economic disparities. Rural areas tend to suffer more economically. As of 2017, poverty rates in rural areas (81.3%) were about double those in urban areas (40.7%). Poverty in rural areas has been exacerbated by the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic, the national hunger crisis, as well as continuous load shedding.

For instance, the largely rural province of Kwazulu-Natal had the highest share of votes for populist parties of all provinces in the 2024 election. Zuma’s populist party MK received 45.3% of Kwazulu-Natal’s votes. Kwazulu-Natal also has the second-highest number of people living in poverty. In Gauteng - an urban, comparatively wealthy province that makes up roughly 33% of GDP and has the highest provincial GDP per capita - voters largely backed the ANC.

Simultaneously, lower voter turnout rates can be more broadly observed in provinces that have higher GDP per capita, with the exceptions of Gauteng and the Western Cape. Moreover, voter turnout in the 2024 elections reached a historic low of 58.6% (in comparison to 89.3% in 1999). This could be indicative of a wider trend in which voter fatigue has driven lower turnouts in ANC strongholds and stronger turnouts in regions where populist parties have wider support.

Assessment:

We assess populist parties are likely to continue to mobilise poorer segments of the population to cast protest votes against the perceived status quo. Additionally, growing disillusionment with the ANC-led coalition will likely lead to further increases in voter abstention among former ANC supporters, reflecting a deepening erosion of confidence in the government. This trend is underscored by the historically low voter turnout observed in the 2024 elections.

This trend is likely to be exacerbated by the rhetoric of populist parties, which particularly target poorer and predominantly ethnically black communities. In the long term, there is a reasonable possibility that this will result in a significant shift in vote distribution, further weakening the ANC and posing a threat to the GNU.

This trend is likely to persist in both future regional and national elections unless the GNU’s policies effectively address the needs of disenfranchised communities. Such measures must include structural economic reforms and effective investments in education, infrastructure, social programs, and poverty alleviation initiatives at the local level.

South African Healthcare: Opportunities & Challenges

South Africa’s healthcare system is gradually emerging from the challenges posed by the Covid-19 pandemic. In the fight against the virus, the healthcare system exhibited a number of successes, however there remain deep flaws that are yet to be addressed. The shortcomings in the government’s response to the pandemic were products of the persistent challenges that the country’s healthcare system has faced for decades. With the new ‘National Health Insurance’ scheme in the pipeline – a medical aid fund aiming to introduce universal health coverage across the country – the South African government must take into account the needs and concerns of its people, the lessons drawn from Covid-19, as well as the broader historical-structural issues that continue to plague the country’s healthcare system.

South Africa’s Healthcare Landscape

South Africa’s constitution grants every citizen the right to healthcare through the private or public sector. Public healthcare is available to all citizens for free, without the need for health insurance. It is largely funded by the National Revenue Fund, which collects payments made to local, provincial, and federal governments. The funds are then distributed from federal to sub-national authorities, who enjoy substantial independence over the allocation of resources, depending on local priorities and necessities.

However, the constitution’s provisions are often not reflected in practice, particularly due to the gap between the public and private sectors. The public sector provides healthcare to 80-85 per cent of the population and accounts for approximately 48 per cent of total healthcare expenditure, while the private sector provides healthcare to the remaining 15-20 per cent of the population and attracts approximately 50 per cent of total government healthcare spending. The remaining 2 per cent is covered by NGOs. Just under 80 per cent of doctors work privately, where they earn higher salaries, leaving only 20 per cent of doctors in the public sector to serve the vast majority of the South African population. This presents a clear disjuncture between the public and private health sector, with major differences emerging in terms of funding, resources, and support.

The public/private healthcare divide often tracks racial lines, raising questions around the legacy of colonialism and apartheid in South Africa’s healthcare system. In the 1986-1987 financial year, just before health services were desegregated in 1988, South Africa’s spending in the former white provinces amounted to $9.30 per capita, compared with $3 per capita in former majority-black areas. Today, access to quality healthcare remains unequal and often contingent on individuals’ ability to pay for private care or live in urban centres. Public healthcare is not allocated based on need, but rather determined by each province’s relative share of the population, thus ignoring factors such as geographic expanse, as well as demographic and implementation specificities.

This legacy of racial-economic inequality is all the more alarming because diseases, such as Covid-19 and HIV/AIDS, often disproportionately affect lower-income populations. South Africa hosts the largest HIV/AIDS epidemic in the world; around 8 million South Africans are currently affected, accounting for 17-20 per cent of global cases. At first, the government’s denial of the virus’s existence resulted in a slow response; however, between 1999 and 2005, spending on HIV/AIDS increased at an average rate of 48.2 per cent annually. Since 1990, the number of people living with HIV/AIDS has continued to increase, but the mortality rate from the virus has been gradually declining since the mid-2000s, thanks to the development and diffusion of antiretroviral treatment.

Source: Our World in Data (2019)

Additionally, South Africa still suffers from a relatively high infant mortality rate, concentrated in remote and poorer areas. In 2018 alone, an estimated 43,000 children under five years of age died in South Africa. In contrast with its African counterparts, South Africa exhibits a relatively high healthcare expenditure, amounting to just over 9 per cent of GDP in 2019, a level of spending surpassed only by Lesotho.

Higher spending on healthcare, however, has not yielded proportional results. South Africa suffers from similar levels of inadequate infrastructure, social inequalities and disease burden as other countries in southern Africa. Yet healthcare systems in Rwanda and Kenya have often performed better and at lower costs. Contrary to South Africa, almost half of Kenya’s poor utilise private healthcare. Both Kenya and Uganda have used mobile health more extensively than South Africa to provide healthcare to low-income communities. In the South African market, there is thus a great amount of space for digital health-focused NGOs and startups to step in and make an impact. South Africa could also benefit from the adaptation and incorporation of policies that have proven successful in other African countries.

Source: Our World in Data (2022)

In 2012, the South African government presented plans to implement a national health insurance scheme over the following 14 years. This health financing scheme, or more precisely fund, is designed to cover the costs of healthcare services for all South Africans, thus aiming to move the country towards universal health coverage (UHC) and to improve the quality of, and access to care. In June 2023, lawmakers approved the NHI and in December, the National Council of Provinces (NCOP) voted in favour of its implementation, with opposition voiced only from the Western Cape province. It must now be signed into law by President Ramaphosa. The NHI broadly aims to address social imbalances in the world’s most unequal society. It envisages the creation of a fund that pools public and private resources, ensuring equal healthcare access and outcomes for all South Africans, regardless of socioeconomic status. The NHI will be funded through public contributions, likely in the form of income-proportional taxes. The policy could deliver various benefits: not only could it lower healthcare costs for South Africans, but also ‘standardise’ salaries and expectations of all healthcare providers. The NHI could also help eliminate health-related barriers to education, drive economic growth by building a healthier workforce, and improve social security, as access to healthcare and education may reduce crime and welfare dependency. Additionally, the NHI could open up opportunities for public-private healthcare collaboration.

Despite widespread support for the NHI and the potential advantages of universal healthcare, as seen in other middle-income countries like Brazil and Thailand, some have raised significant concerns, particularly with regards to the NHI’s implementation. First, the NHI’s funding remains a key point of contention, as its estimated cost runs over $27 billion annually. Critics point to South Africa’s weak tax base, due to the high number of people working in the informal sector, as well as slow economic growth, as evidence for impending financial challenges and increased tax burden for citizens. These worries are heightened by recurring allegations of governmental corruption and poor administrative oversight. Second, private healthcare providers have expressed concerns about the uncertainty regarding their role in this new system, highlighting the danger of job losses should the private sector not be effectively integrated. Medical practitioners may also choose to leave South Africa in search of better paid jobs, contributing to a resource shortage in the public sector. Third, critics fear that the NHI may result in lower quality healthcare, as the government does not have enough resources to meet the needs of all South Africans. Fourth, the proposed NHI framework is unclear on several issues, including the range of treatments to be covered and the rate of reimbursement. The South African government will therefore need to address the lack of trust in the NHI’s potential by outlining a concrete roadmap, evidencing the scheme’s ability to offer reliable as well as inclusive access to healthcare, and dispelling views of the proposal as a mere idealistic utopia.

Successes in South African Healthcare

In recent years, and particularly in response to Covid-19, South Africa’s healthcare system has had notable success.

Since the mid-1990s, the country has reduced maternal and under-5 mortality rates, as well as death rates from infectious diseases. It has also expanded immunisation programs, which were, however, paused during the Covid-19 pandemic to comply with national lockdowns.

Many healthcare organisations have created innovation teams and digital strategies to follow developments in AI, telemedicine, and digitisation. Both the public and private sector have also improved data analytics capabilities to track shifts in healthcare needs and resource availability in order to identify key risks and opportunities. These measures have, for instance, contributed to promising advances in the use of nanotechnology for cancer treatment. The Covid-19 pandemic further encouraged South Africa’s healthcare sector to gradually, but comprehensively embrace digital technologies, not just for data analytics, but also to support the accelerated adoption of virtual healthcare, which has helped reduce pressures on facilities and minimise inequalities.

Macro- and micro-level healthcare initiatives have jointly widened access to care. At the national level, the ‘Transnet Phelophepa Health Trains’ have helped treat 200,000 patients annually by taking mobile clinics into rural areas through South Africa’s railway system. At the local level, in 2013, a Cape Town resident founded the ‘Iyeza Express’ bicycle courier service, which employs local youth to collect medication from public health facilities and deliver them to people’s homes, particularly in the city’s poorer districts. In the same year, to reduce time spent queuing at health facilities, a Johannesburg local created ‘Pelebox Smart Lockers’, which sends a PIN to patients’ mobile phones to open lockers containing prescribed medications. These initiatives have boosted the efficiency of South Africa’s healthcare system.

Challenges in South African Healthcare

Despite noteworthy successes, the South African healthcare system has encountered a number of challenges that have impacted its performance. These challenges have fed many of the criticisms that are now directed against the proposed NHI.

Most importantly, South Africa’s healthcare system has suffered from a lack of resources and personnel, particularly when considering the country’s large population and ‘quadruple disease burden’ (HIV/AIDS, communicable diseases, non-communicable diseases like diabetes, and violence and injuries). The Covid-19 pandemic highlighted that the needs of South Africans exceed the country’s healthcare system’s human, material, and financial capacities. Throughout the pandemic, underfunded and understaffed hospitals handled insufficient and outdated equipment, while following constantly changing protocols. Long work hours, extended waiting times, and overcrowded health facilities became the norm, particularly in rural areas. South Africa’s weak primary healthcare system, the lack of political will, and the government’s underestimation of Covid-19’s severity meant that the virus was not thwarted in its early stages. The mismanagement of the pandemic also led to the stigmatisation of communities with high Covid-19 cases, increased episodes of gender-based violence, and social discrimination in the distribution of food aid.

In part resulting from the country’s limited resources and staff, economic, racial, and geographic inequalities remain a keystone of South Africa’s healthcare system. The private and public sectors, as well as urban and rural localities, display massive healthcare imbalances, in terms of quality and access. In regards to the former, South Africa’s private clinics charge fees that are commensurate with those of significantly wealthier nations, due to the lack of pricing regulations. This practice has made private healthcare inaccessible for the majority of South Africans. During the pandemic, access to testing and vaccines was clearly determined by individuals’ ability to pay, with lower-income groups left behind. This outcome was, at least partially, a result of the government’s insufficient spending on public healthcare. This policy does not follow from an established norm of obtaining healthcare from the private sector, as in the United States; rather, it represents an extension of South Africa’s apartheid-era policies that cater to a small, rich section of the population.

With regards to the rural-urban gap, residents of major urban centres have a significantly higher chance of receiving treatment than people living in rural areas, due to the disproportionate concentration of health facilities in large cities. Apartheid-era urban planning has meant that health clinics remain inaccessible to the majority of South Africans, for financial and practical reasons. Additionally, the marked disparity in skill between urban and rural regions contributes to persistent inequalities in terms of the quality and outcomes of healthcare. This inequality has nurtured a low ‘acceptance’ of the national public healthcare system among many South Africans, with patients being not only unable, but unwilling to seek treatment due to, for instance, perceptions of (in)efficiency, language barriers, and ethnic and religious under-representation.

However, micro-level initiatives have helped redress skill shortages in rural areas. The ‘Umthombo Youth Development Foundation’, for example, provides medical scholarships to students from remote areas. The aim is that these students later return to their home communities to offer healthcare that is perceived as more trustworthy, credible, and thus more effective. Here, healthcare startups and community or national-level NGOs can thus play a key role: they can first focus on assisting the expansion of existing programs, including the ‘Iyeza Express’ and the initiative developed by the ‘Umthombo Youth Development Foundation’, both locally and nationally. Second, given the South African government’s limited resources, these organisations can prioritise providing financial and logistical support for the development of new initiatives, particularly those geared towards improving remote areas’ access to quality healthcare and those encouraging community-based health education and university-level medical education, in an attempt to raise health awareness and redress the country’s shortage of health personnel.

Rampant corruption, and the lack of enforcement and accountability mechanisms to counter it, pose a major barrier to progress in South Africa’s healthcare system. Private healthcare providers, for example, reportedly submit inflated or forged claims of treatment to private health insurance schemes to maximise their revenue. The difficult response to Covid-19 was exacerbated by widespread corruption, abuse of funds, and the syphoning of scarce resources away from rural clinics.

Looking Ahead

In light of these challenges, South Africa’s healthcare sector faces a set of key risks in years to come. First, persistent resource shortages and the country’s dependence on imports from countries such as India and China will continue to dictate the trajectory of its healthcare system. Without substantial investment in the domestic manufacturing industry, progress in healthcare provision will be constrained by a resource bottleneck and may also become affected by foreign interests. Nevertheless, like many other countries in Africa, South Africa is well-positioned for the development of innovative healthcare practices and technologies that address constraints such as resource scarcity. Second, in view of the NHI’s implementation, talent retention will remain a key challenge, as skilled healthcare workers, particularly from the private sector, may choose to leave South Africa in search of more profitable opportunities. Third, while technology will be central to the expansion of care in South Africa, it will also increase the country’s vulnerability to cyberattacks, which it is not yet equipped to counter. There is thus a need for increased private-public cooperation to develop stronger national cybersecurity infrastructure.

Despite such risks, South Africa is now at a critical juncture, navigating the aftermath of a devastating pandemic, nearing the deadline for the NHI’s implementation as well as the 2024 general elections, and situated amidst a global technological revolution. The country faces a pivotal opportunity to reform its healthcare system in line with the lessons learnt from past failures:

In the first place, as highlighted by the country’s experiences with HIV/AIDS and Covid-19, South Africa should invest in preventive measures, including R&D and risk outlook units, to better monitor and predict outbreaks of infectious diseases.

Second, the incoming South African government must strengthen its leadership before implementing the NHI, for example by facilitating meaningful public-private partnerships and by fostering communication between key players. At present, different parts of the public system are managed by different government units, while private doctors operate in isolation from one another. South African leadership should instead promote linkages, or even integrate, the private and public sectors, as the former generally has more resources than necessary to treat its patients and as such, can help fill major gaps in the public sector.

To enhance its credibility and legitimacy, the incoming government must also cultivate public trust in the healthcare system and the NHI, if it decides to persevere with its implementation. It must clarify the NHI’s provisions, encourage transparency, and promote accountability to address corruption. It can do so by making performance data publicly available to encourage improvements on the provider side, while keeping clients informed on relevant developments. It can also establish city-wide integrated management teams to replace the current fragmented system and to redirect financial oversight from the national to the city level to reduce the risk of corruption, a model that proved successful in the Chinese province of Sanming.

The government could also develop education initiatives to raise awareness about the current medical system and the potential benefits of universal healthcare, to enhance support for the NHI. Additionally, framing better healthcare outcomes as beneficial for South Africa’s long-term economic growth can encourage wider domestic support as well as foreign direct investment.

Third, and more broadly, the government will have to ensure that the transition towards universal healthcare involves all relevant stakeholders in the public and private sector, at the local and national level, in and beyond South Africa. It must carefully balance actors’ competing interests and concerns before the NHI is implemented. In particular, South Africa should capitalise on the opportunities offered by new and existing international partnerships to unlock the healthcare sector’s full potential. Although South Africa is one of the least aid-dependent states in Africa, international donors and financiers can provide critical funding and resources, support capacity-building, share best practices, and catalyse the wider delivery of healthcare services. At the same time, South African leadership should support micro-level initiatives like the Iyeza Express, which will prove valuable to reach the most vulnerable and better respond to the needs of remote communities.

Fourth, South Africa can benefit from adapting and adopting successful policies from fellow African countries and other middle-income counterparts worldwide. For example, Malawi’s toll-free health hotline represents one of the many strategies that South Africa could implement to provide communities with reliable access to virtual care and remove the need to travel long distances to the nearest facilities. South Africa can also learn from Mexico’s and India’s experiences with universal healthcare, which have respectively highlighted the benefits of effective regional governance to complement national leadership, and the importance of human and physical infrastructure to drive meaningful change.

Perhaps most importantly, Rwanda’s successful universal healthcare policies can provide a useful model for South Africa, as the two countries lack extensive public resources and must overcome a legacy of conflict and inequality. Rwanda’s healthcare system fundamentally rests on a community-based health insurance scheme, known as ‘Mutuelles de Santé’, whereby residents of particular areas contribute to a local health fund, supported by the state and international agencies, and which they draw from when necessary. The poorest do not pay anything, while richer individuals may be responsible for co-payments. To sustain this system, the Rwandan government has supported the deployment of community health workers to the country’s 15,000 rural villages, as well as the establishment of health posts in remote areas to cut patients’ average walking time to care facilities in half, from 47 minutes in 2020 to 24 minutes in 2024. These initiatives have helped close gaps in access to healthcare and have built a workforce that is more receptive to its population’s healthcare needs.

Source: KPMG (2017)

The incoming South African government must ultimately focus on balancing the goal of achieving universal healthcare with the quality of care itself, as well as with economic and political realities. It should harness contemporary digital advances, utilise lessons learnt thus far from its experiences with HIV/AIDS and Covid-19, take on board popular concerns with the proposed NHI, and approach healthcare as a human right.

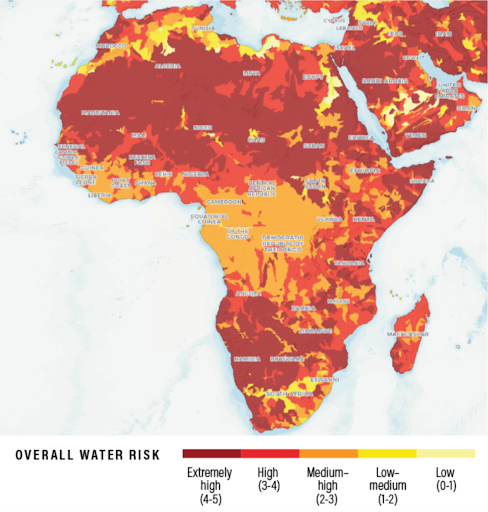

Water Scarcity in Africa: A Changing Landscape of Challenges and Opportunities

The right to water, as recognized by the United Nations, entitles all individuals to access to sufficient, safe, physically accessible, and affordable water. However, this right is not reflected in practice. The African continent has suffered from a water scarcity crisis for decades. Its implications on communities’ food, health, and economic security have been critical and have not been effectively mitigated by governments or international humanitarian actors. There is an urgent need for improved infrastructure and governance, enhanced international cooperation, and greater awareness about the effects of water scarcity to tackle the crisis in Africa and ensure that all individuals are provided with enough clean water to meet at least their basic needs.

Drivers and Recent Trends

Water scarcity in Africa has developed into a complex emergency. Changing climate patterns, a rapidly growing population, inadequate infrastructure, and poor governance have contributed to a critical water crisis that threatens both the health of the African population and the stability and development of the entire region.

Of the 23 countries worldwide labelled as ‘critically water-insecure’ by the UN Institute for Water, Environment and Health, 13 are located in Africa. These countries are characterised by low levels of access to safe drinking water, sanitation services, and water resource stability. Africa has the lowest levels of safe water access of any continent; in 2020, only 15 per cent of the continent had access to safe drinking water. In Chad, nearly 50 per cent of the population consumes drinking water with very high levels of E. coli, while just 6 per cent has access to safely managed potable water.

Over the past five decades, despite advancements in access to safe water and sanitation around the world, since 2020 Sub-Saharan Africa has witnessed an increase in the proportion of its population lacking access to secure potable water services. An estimated 70 per cent of people in Sub-Saharan Africa lack safe drinking water services.

Source: Naddaf 2023

Several mutually-reinforcing factors are contributing to Africa’s water scarcity crisis. First, the continent’s climate, characterised by high temperatures, variable rainfall, and harsh aridity, has contributed to both desertification and intense flooding. While Africa has the highest number of countries at high risk of droughts, there remains a severe threat of flooding, as evidenced in Somalia and Ethiopia earlier this year.

Second, Africa’s rapid population growth is increasing the demand for water resources. Sub-Saharan Africa’s population is growing at 2.7 per cent annually, which is more than twice as fast as South Asia (1.2 per cent) and Latin America (0.9 per cent). This is placing immense pressure on the continent’s water and food resources, especially as these are gradually being depleted by (largely human-induced) forces such as climate change.

Third, government policies have been unable to slow these trends. Distinguishing between physical and economic water scarcity is fundamental to understanding the implications of water scarcity and devising appropriate responses. Physical scarcity refers to the condition wherein available water resources fall short of fulfilling the needs and demands of the population. On the other hand, economic water scarcity arises where, despite the natural availability of water, access to water is limited due to a lack of infrastructure, high costs, and institutional constraints – in other words, due to poor policies and governance.

Arid regions of the continent, mainly located in North Africa, are characterised by physical water scarcity, whereas Sub-Saharan Africa predominantly experiences economic water scarcity. Interestingly, water stressed countries, particularly Algeria, Libya, and Egypt in the North, and Namibia, South Africa, and Botswana in the South, make water available to a higher proportion of people than in countries with abundant water resources, like the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC). The DRC possesses over half of Africa’s water reserves and receives frequent rain, yet lacks the infrastructure and regulations to provide millions of Congolese with access to clean water. Even within countries, economic water scarcity impacts individuals differently, as it acts upon existing socio-economic inequalities dictated by income, gender, race, level of education, or political beliefs. These statistics highlight the role of government policy in ensuring an equitable distribution and supply of safe water for citizens.

Economic water insecurity is often derived from poor regulatory mechanisms governing the use of bodies of water. The pollution and contamination of water have become critical issues, stemming at least in part from the mismanagement of agricultural, animal, and industrial waste, as well as the overexploitation of bodies of water, as in South Africa. As a result, contaminated water is often utilised in households, particularly in settings where alternative water sources are unavailable.

Fourth, private companies and organisations have attempted to profit from Africa’s limited public water access by privatising water. This has rendered water an increasingly elusive resource by making it more expensive and inaccessible. In areas worst hit by droughts, in the Horn of Africa for example, the cost of water has increased by up to 400 per cent, leaving many without enough water to meet basic needs. Water privatisation has thereby widened inequalities, while also potentially creating opportunities for corruption. In Uganda, “private contractors estimated the average bribe related to a contract award to be 10 percent (of the total cost),” meanwhile an estimated 46 per cent of urban water consumers pay extra money to connect their households to a water network. Corruption ultimately inflates water prices, thus denying poorer segments of the population access to water.

Fifth, climate change is further complicating matters. The Horn of Africa region, for example, is in its fourth consecutive year of drought and is experiencing the impacts of “one of the worst climate-induced emergencies of the past 40 years.” The region’s minimal rainfall has triggered a water scarcity crisis, with more than 8.5 million people, almost half of them children, facing dire water shortages. This represents merely one instance amid a multitude of cases across the continent.

The Implications of Water Scarcity

The water scarcity crisis in Africa has, and will continue to have, important consequences at the local, regional, and international level. Not only does it critically impact human security, but is also intensifying migration flows and exacerbating conflicts, thereby requiring regional and international bodies to step up their operations to respond to growing humanitarian emergencies.

First, water scarcity has a prejudicious effect on the continent’s human security. The lack of safe, accessible drinking water increases the likelihood of chronic dehydration, particularly in areas with arid climates. Water scarcity also compromises food security and livelihoods. A large proportion of the African population is reliant on agriculture, farming, and fishing for both personal consumption and as a source of income. The inconsistent access to and supply of water reduces crop yields and the availability of food, exposing communities to critical socio-economic and health vulnerabilities. Moreover, water scarcity contributes to environmental degradation; parts of Africa have witnessed increasing desertification and a loss of biodiversity, which compounds existing challenges to livelihoods. For example, over one-third of Burkina Faso’s farmland is degraded as a result of both prolonged periods of drought and improper land use, thus gravely impacting the population’s food and economic security.

From a macro-level perspective, water scarcity can also slow economic growth. Inconsistent agricultural yields and industrial productivity that contribute to persistent poverty and famines, make water insecurity a critical impediment to economic development. Simultaneously, limited food outputs can induce inflation and thus impact both national and global food prices.

Water scarcity also significantly increases the likelihood and spread of diseases, such as cholera and diarrhoea. An estimated 842,000 people die from diarrhoea every year as a result of unsafe drinking water, sanitation, and hygiene. Access to hand-washing facilities ranges from 25 per cent of the population in Chad, to just 9 per cent in Burkina Faso. In regions characterised by water scarcity, communities are less inclined to allocate water resources to hygiene-related activities, thereby augmenting the probability of disease proliferation and transmission.

Source: Our World in Data 2019

Water scarcity’s impact on human, health, and economic security inherently reinforces inequalities. While communities living in rural areas, informal settlements, or low-income settings often struggle to meet their basic water needs, individuals in comparatively advantageous socio-economic positions are able to access privatised sources of water. Water scarcity disproportionately impacts the most vulnerable people, including children who are at a greater risk of developing conditions stemming from malnutrition, such as stunting and diabetes. Water insecurity may also exacerbate gender inequalities; when water is not easily accessible, the burden of travelling to collect it often falls on women and girls. This represents a “high opportunity cost to obtaining education or employment.”

Second, water scarcity is a driving factor for migration. Internal displacement in African countries has significantly increased in recent years due to persistent conflict, resource scarcity, and natural disasters. In Burkina Faso, the number of internally displaced persons (IDPs) grew from less than 50,000 in October 2019 to around 2 million in March 2023. Inherently, migration hinders the ability to secure stable and reliable access to water resources. Rural-urban migration, towards Nairobi and Mombasa for instance, has led to overcrowding in cities not equipped to deal with overpopulation, placing huge strains on water resources, further intensifying water scarcity. Water insecurity has also driven transborder migration, increasing the demand for, and pressure on, water resources in neighbouring countries. The almost-total disappearance of Lake Chad, a vital source of water and livelihoods for 30 million people in the Sahel, has forced the displacement of three million people and has left 11 million people in need of humanitarian assistance. The combination of resource shortages, forced migration, and pre-existing tensions has served to trigger violence between fishing, farming, and herding communities.

Third, water insecurity has contributed to the provocation of conflict on the African continent, both within and across borders. Violent clashes have, in turn, exacerbated human security and triggered further migration and conflict. Beyond Lake Chad, tensions have emerged between Egypt, Sudan, and Ethiopia over access to the Nile Basin, especially after the latter began the construction of a hydroelectric dam that Egypt claims could drastically reduce water flows into the country. Moreover, the potential for, and fears of, transboundary conflict have triggered intra-state discontent. For example, the development of the ‘Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam’ heightened the Egyptian public’s concerns about reliable water access and generated significant pressure on the government to respond firmly. Furthermore, human dependence on water has been intentionally exploited during conflicts; water resources, systems, and infrastructure required to deliver water have come under direct attack. In fact, children under the age of 5 living in conflict zones are 20 times more likely to die from diseases linked to unsafe water and sanitation than from direct violence.

Fourth, on a more global scale, the combination of famines, droughts, diseases, migratory flows, and armed conflicts resulting from water scarcity in Africa have generated an urgent demand for international humanitarian interventions. The international community is confronted with growing expectations regarding the coordination of increasing volumes of aid to help African governments mitigate the local impacts of water stress. Additionally, international actors must overcome barriers to the access of remote or crisis-affected settings to ensure the timely delivery of essential water resources and facilitate the development of vital infrastructure. The international community finds itself at a critical juncture as current efforts to address the unfolding water scarcity crisis hold the potential to shape long-term trajectories and trends.

Looking Ahead: Challenges and Opportunities

Evidently, the water scarcity crisis entails significant risks and challenges for African governments and the international community in years to come. Current trends indicate that water scarcity, as well as its consequences for human security (including famines, poverty, inequality, health insecurity, migration, and conflict) are likely to worsen. Both climate change and Africa’s rapid population growth will place increasing pressure on the continent’s water resources, while central governments may lack not only the capacity, but also the political will, to respond adequately. Guaranteeing equitable access to safe, clean, and sufficient water to meet individual basic needs, both personal and economic - and thus preventing the onset of large-scale humanitarian crises - will represent a critical governance challenge in coming years. Measures must be taken to improve national water management, storage, distribution, and recycling capacities, especially through infrastructure expansion. Governments will have to recentre their efforts towards preventing and managing water scarcity, instead of merely attempting to deal with its consequences.

At the same time, the unfolding challenges linked to water scarcity in Africa present important opportunities for both governments and the international community. First, huge potential exists for states to invest in and develop durable infrastructure to ensure the reliable supply of clean water to homes. This specifically includes piped water systems, which can help provide communities with readily available drinking water, while removing the need for women and children to travel long distances and forgo education or work. This would inevitably increase children’s school attendance and free up time for women to engage in more productive activities, which would have positive implications for countries’ economic growth.

Simultaneously, governments should invest in the development and distribution of sustainable, water-efficient, climate-resilient practices and technology, such as drip irrigation, reforestation, and the extraction and recycling of groundwater, to sustain livelihoods and mitigate physical water scarcity in the long term. Thus far, “water resources harnessed and land area developed for irrigation in Africa are still far below the (region’s) potential,” opening up an opportunity to fill this gap. The digitisation of agriculture and farming would significantly help conserve water resources and render activities more productive and efficient, thus contributing to communities’ food, health, and economic security. Some African countries have already taken important steps in this regard: Namibia has improved urban wastewater management in Windhoek, recycling sewage water into drinking water, meanwhile the Kenyan government has sought to increase the distribution of drought-tolerant maize varieties.

Equally important is the need for improved data collection; governments must cooperate with sub-national actors to expand the available data on both physical and economic water scarcity, to ensure that implemented projects yield desired results and are endorsed by recipient communities. All the above efforts can be pursued jointly by national governments, the private sector, and the international community.

Relatedly, the water scarcity crisis presents an important opportunity to enhance cooperation on water management at the regional and international level, whether through development institutions, regional bodies, or inter-state frameworks. Currently, multilateral efforts to combat climate change and reverse water scarcity trends in Africa are insufficient. There is still no global framework for addressing water stress, like there is for climate change and the preservation of biodiversity. Water insecurity must be prioritised on international and regional agendas. State and non-state actors alike should increase their support to African governments, through capacity-building programmes, disbursements of financial assistance, exchanges of technical expertise, and infrastructure development.

The United States’ Partnership for Global Infrastructure and Investment (PGII), developed in 2022, represents a good starting point, as it seeks to mobilise private capital investment towards infrastructure linked to climate and energy security, digital connectivity, health security, and gender equality. Such goals could support important investments in water infrastructure. Yet this initiative does not go far enough to prioritise the issue of water scarcity and forefront the urgent need for improvements to water management policy and infrastructure in Africa.

Source: Our World in Data 2021

Meanwhile, within Africa, the African Risk Capacity (ARC) Group, as part of the African Union, has been playing an important role in tackling water scarcity. Its sovereign insurance mechanism has paid out over $36 million to African countries affected by drought since 2014, preventing further famines, poverty, and health insecurity. However, this framework has mainly focused on assisting countries to respond to the effects of water scarcity, rather than encouraging the development of infrastructure and technology that can mitigate and prevent these effects in the first place. Despite providing important assistance in times of crisis, more needs to be done to ensure that all individuals across Africa obtain reliable access to safe, clean, and readily available water before having to suffer the impacts of water scarcity.

Lastly, there is a crucial opportunity to enhance education and raise awareness about water scarcity and its effects, particularly on human health. Governments must invest in initiatives aimed at encouraging behavioural changes, particularly where water scarcity is less pronounced, and promoting climate-resilient agricultural practices. Central governments must simultaneously support bottom-up, micro-level initiatives seeking to tackle both the causes and effects of water insecurity. Only through a combination of local, regional, national, and international efforts can the current water scarcity crisis be mitigated and communities across Africa be provided with long-term access to clean, safe, and affordable water.

Nigerian Senate Opposes ECOWAS Military Intervention in Post-Coup Niger

The recent coup in Niger led by the head of the presidential guard, General Abdourahmane Tchiani, was met with extensive condemnation, both regionally and internationally. Principally, the Nigeria-led ECOWAS bloc imposed various economic and travel sanctions against Niger to pressure the coup leaders to reinstate democratically-elected President Mohamed Bazoum. The West African organisation also issued a one-week ultimatum to the putschists, which if ignored, would entail a military intervention. ECOWAS claimed the use of force would be a “last resort”. The bloc aimed to develop a detailed plan for the use of force, including the resources needed and the timing of a possible intervention. Meanwhile, the Nigerian president and head of ECOWAS, Bola Ahmed Tinubu, expressed his support for Bazoum. He declared that “[w]e will stand with our people in our commitment to the rule of law” and signalled Abuja’s “readiness to intervene” in Niger as soon as ECOWAS gave the order. Additionally, Nigeria stopped supplying electricity to Niger - Niger depends on Nigeria for around 70% of its electricity.

Despite these measures, Niger’s coup leader has repeatedly claimed he will not give into pressure to restore President Bazoum. Instead, General Tchiani has proceeded to form his government, naming a 21-member cabinet and appointing a new prime minister, Ali Mahaman Lamine Zeine, to replace Ouhoumoudou Mahamadou. Given the putschists’ steadfastness and Nigeria’s stern response to the coup, calls for a Nigerian-led ECOWAS military intervention were to be expected. Yet, on 6 August, Nigeria’s senate rejected Tinubu’s plan to send forces to Niger. It instead encouraged ECOWAS to pursue “political and diplomatic options” to resolve the crisis in Niger. This will undoubtedly give the military junta a respite.

Why Oppose an ECOWAS Military Intervention in Niger?

Although an ECOWAS-led intervention in Niger may have helped Nigeria boost its regional geopolitical standing and restore political stability in its neighbourhood, the senate’s decision to oppose this measure was not senseless. Several factors may have informed its ruling on 6 August.

Within Nigeria many believe that President Tinubu’s assertiveness abroad constitutes an attempt to distract from domestic problems, and shore up much-needed popularity. Tinubu has been accused of electoral misconduct and has been criticised for his slow response to the country’s economic and security challenges, including the continued Boko Haram attacks across North Eastern Nigeria. Accordingly, the public has been vocal in denouncing Tinubu’s ‘unnecessary’ external interference. The Nigerian senate may have similarly recognised a need to refocus the regime’s attention to domestic issues. Nigeria’s participation in ECOWAS’s planned intervention may have further risked jeopardising relations with Niger, which remains an important partner in the Nigeria-led joint force fighting armed groups in the Lake Chad region.

While the coup leaders cement their hold on power in Niger, the resistance to a potential ECOWAS intervention is growing. Within Niger, the public has widely shown its support for General Tchiani while President Bazoum has found little support on the ground. Although a former Nigerien rebel and politician has recently launched a movement to oppose Tchiani’s coup, this merely constitutes an incipient campaign that will likely be quashed by the military junta. Public rallies have also evidenced Nigerien citizens’ disapproval of the continued French presence in the country, in which many demonstrators openly displayed support for Russia. Although Niger is one of the world’s poorest countries, its military has been trained to fight jihadists by France and the United States, and may thus have the capability to successfully oppose forces deployed by ECOWAS. Importantly, Niger’s troops would not be fighting alone; Mali, Burkina Faso, Guinea, as well as Algeria, Mauritania, and Benin have expressed their support for Niger’s new leaders in the midst of a possible ECOWAS intervention. Mali and Burkina Faso have gone further, exclaiming that any attempt to restore Bazoum would be treated as a “declaration of war” against them all. Additional support from private actors like the Wagner Group may also have bolstered Tchiani’s ability to defend against an ECOWAS invasion. ECOWAS’s internal challenges would likely have undermined its prospects for success in Niger, and may have thus pushed the Nigerian Senate to reject ECOWAS’ plans for intervention.

Analysts have claimed that ECOWAS doesn’t possess the military capacity to launch an operation in Niger. Although the West African bloc intervened in The Gambia in 2017, when former President Yahya Jammeh refused to step down after his electoral loss, the intervention was largely possible because ECOWAS was “invited in by the Banjul government.” ECOWAS also suffers from a lack of coordination in providing security regionally and often fails to align its policies with those of other regional organisations. For example, ECOWAS gave the Niger junta a one-week deadline to reinstate President Bazoum while the African Union issued a 15-day ultimatum. Insufficient trust among ECOWAS members would have further compromised any attempt to mount a strong front against General Tchiani. Lastly, western support may have been necessary to address ECOWAS’ financial and logistical difficulties. The Nigerian Senate’s approval of a western-backed ECOWAS intervention would likely have sparked more protests and resistance in Niger, as well as more divisions within the West African bloc.

An ECOWAS-led intervention would have also carried the risk of further escalation; a mere attempt to restore President Bazoum could have ushered in a war transcending multiple African countries. Even in the best-case scenario, an intervention would have likely compelled ECOWAS troops to remain in the country for a lengthy period. This would strain countries’ military budgets and make “Bazoum look like he is only a president because of foreign armies, and that [would] destroy his legitimacy.”

Lastly, civilians would have likely borne the greatest costs of an ECOWAS military intervention. ECOWAS troops have a suboptimal record when it comes to avoiding collateral damage. Before parliamentary talks on 6 August, Nigerian senators issued a joint statement claiming they would not accept military action in Niger because it could worsen the humanitarian crisis in northern Nigeria. Refugee flows from Niger, which shares a 1,600 kilometre border with Nigeria, would have strained the central government’s capacities.

Looking Ahead: A Multi-Level Strategic Predicament

The Nigerian Senate’s rejection of ECOWAS’s plans for a military intervention presents an important question: What’s next? As the West African bloc struggles to find an alternative solution to the coup in Niger, the implications of the abortive ultimatum and intervention are becoming increasingly evident. ECOWAS’s credibility will undoubtedly take a hit. The West African bloc had been criticised for its poor response to the coups in Burkina Faso, Guinea, and Mali in recent years. The lack of firm retaliation against the Nigerien military junta reiterates this pattern and will further harm ECOWAS’s perceived relevance and effectiveness. ECOWAS’s failure to respond militarily also reveals important cracks in the alliance, as countries scrambled to pick a side between the wealthier pro-democracy states and their military-led counterparts.

The senate’s rejection of ECOWAS’s plans will have grave implications for West African geopolitical stability. First, ECOWAS’s weak response will have a significant impact on how politics will be conducted in the region; it may provide leaders across the region with a ‘green light’ to stage coups or ignore constitutional limits. As such, the use of force may increasingly supersede the rule of law. As a result, democracy in West Africa remains very fragile. Additionally, the lack of military retaliation will open up space for greater Russian presence in Niger and in the wider West African region, at the expense of western influence. In particular, the Wagner group may capitalise on its existing ties in Mali and Burkina Faso to expand its reach into Niger.

The coup will also likely undermine the efficiency of the western-backed anti-terrorism campaign across the Sahel. Niger has been a key ally and security buffer for western states against al-Qaeda and Islamic State insurgent groups, but the recent coup will likely affect collaboration on counter-terrorism. The new Nigerien leadership will unlikely view the west as a valued partner, but rather as a colonial power. Thousands of French troops were forced to withdraw from Mali and Burkina Faso after their respective coups. As foreign armies retreat, terrorist and armed groups will be able to exploit political instability and uncertainty throughout political transition periods to expand their operations. Islamic extremists may intensify their recruitment exercises and violent campaigns. This occurred in Burkina Faso after its coup last September.

As the putschists continue to strengthen their political authority and support base in Niger, the West African bloc is at a crossroads. Realistically, ECOWAS’s alternatives to resolve the crisis are now largely limited to diplomatic avenues and/or continued sanctions. Both should not be discounted as pathways towards stability. Yet both unfortunately seem to have bleak prospects. On one hand, repeated attempts at negotiations over the past week have yielded little progress. Nigeria may be able to utilise the existing commercial and diplomatic relationship between Nigeria and Niger to pressure the military junta into backing down, but this outcome does not seem probable. Niger’s new leaders retain key leverage, as Bazoum constitutes a valuable bargaining tool. Tchiani is therefore unlikely to surrender. Further, ECOWAS sanctions have thus far had little impact on decisions made by the Nigerien military junta.

On Tuesday, ECOWAS imposed more sanctions on Niger after General Tchiani denied a joint delegation from West African states, the African Union, and the United Nations permission to enter the country. Yet, the sanctions will unlikely be effective. In both Mali and Burkina Faso, sanctions were lifted soon after they were imposed. Instead, sanctions will likely harm civilians already facing acute poverty and hunger. Sanctions may also prove politically counterproductive; in Mali, the military junta was able to use the “international campaign against Malian sovereignty” to rally people behind it and gain legitimacy.

Niger’s neighbours and the international community are now faced with a critical strategic predicament. Irrespective of ECOWAS’s next strategic move, there is a need for extreme caution. If not properly managed, the coup in Niger may set the stage for similar political disruptions elsewhere, produce deep rifts among African countries, and may eventually be overlooked.

Attacks on LGBTQ+ Rights in Uganda

Whilst communities worldwide celebrate Pride throughout the month of June, the Ugandan LGBTQ+ community has been forced into hiding. On 26 May, Ugandan President Yoweri Museveni signed into law one of the world’s toughest anti-homosexuality acts. The bill has attracted widespread international condemnation. Most importantly, it has critically impacted the lives of LGBTQ+ individuals, both within Uganda and in the broader region.

LGBTQ+ Rights in Africa

Uganda’s newest legislation emerges within a wider context of widespread homophobia. The African continent still imposes more anti-LGBTQ+ laws than many other parts of the world. Few national legal frameworks offer basic protections for LGBTQ+ individuals, particularly from rampant discrimination in schools and workplaces. Most countries instead prescribe stringent and restrictive policies against LGBTQ+ communities. Fines and prison time are common penalties for same-sex relationships and gay sex. Nigeria imposes flogging as punishment, while other countries like Mauritania, Sudan, and Somalia, stipulate the death penalty. Ghana introduced a strict anti-gay bill in late 2022, while Kenya and Tanzania have recently introduced strict legislation alongside Uganda. Meanwhile, countries where homosexuality is decriminalised, like Egypt, have adopted “vague laws against prostitution [...] and ‘debauchery’” to surveil those deemed to be LGBTQ+. Legislation in African countries largely mirrors public sentiment; polls conducted by Afrobarometer between 2016 and 2018 found that 78% of Africans across 34 countries were intolerant of homosexuality. Analysts have pointed to several contributing factors, including the legacy of colonialism, the influence of the Christian and Islamic religions, and modern African electoral politics. To win support and downplay their failures, politicians have demonised LGBTQ+ identities as “contrary to culture norms” and as a “western import that threatens social cohesion.”

As a result, LGBTQ+ communities across Africa are frequent victims of violence, hate crimes, and long prison sentences. In many countries, the extent of violence is likely under-estimated, as many instances go unreported. LGBTQ+ individuals also suffer from limits on their freedom of expression, as governments ban LGBTQ+ rights groups from registering as NGOs and instruct police forces to raid pride events. Media outlets often spread disinformation about LGBTQ+ individuals, which perpetuates stigma. Additionally, gay men are disproportionately affected by illnesses like HIV, but refrain from seeking medical assistance out of fear.

Nevertheless, there has been some progress. Same-sex relations are currently legal in 22 of Africa’s 54 countries, up from 15 in the 1990s. Countries like Angola, Botswana, Gabon, and Mozambique have all decriminalised homosexuality in the last decade, while Namibia has recognised same-sex marriages abroad. An Afrobarometer poll found that majorities in Cape Verde and Mauritius are tolerant of homosexuality. South Africa remains the most accepting country in the continent, as its constitution uniquely safeguards LGBTQ+ people. It prohibits discrimination of LGBTQ+ communities and allows for same-sex marriage. However, a 2016 International LGBTI Association poll revealed that only 40% of South Africans approved of same-sex marriage and human rights activists have reported a lack of enforcement of LGBTQ+ rights.

Despite the extensive risks, LGBTQ+ communities across Africa have continued to push for social change, particularly in the midst of social unrest. In 2020, the Nigerian LGBTQ+ population capitalised upon the #EndSARS movement against police brutality to promote inclusivity. This was especially important for queer people, suffering disproportionately at the hands of police and security forces.

Uganda’s New Anti-LGBTQ+ Law