The Risks Presented by Poverty, Inequality and Unemployment in South Africa

Executive Summary

London Politica assesses with high confidence that increased poverty, unemployment, and inequality levels will likely continue to drive crime, unrest, and the rise of populist parties in South Africa. This will likely negatively impact the perceived legitimacy and support of the Government of National Unity (GNU) coalition.

To address these challenges effectively and maintain popular support, we assess that the GNU would benefit from investments in infrastructure targeting electricity and water supply, as well as social programs, education and poverty alleviation initiatives at the local level. The implementation of structural macroeconomic reforms to improve living standards and public sector efficiency would also likely continue to improve the country’s business climate and attract foreign investment.

Declining unemployment rates are expected to strengthen demand-driven growth, as evidenced by the 1.3% increase in household consumption following the election. This will likely reinforce business confidence and accelerate the expansion of key national industries, including mining, construction, manufacturing and electricity.

Despite growth in key domestic sectors, economic activity declined across government consumption, imports and exports, contracting GDP by 0.3% in Q3. Persistent trade weakness, driven by declining imports of minerals, precious metals and machinery will likely further constrain trade flows in the near term, limiting the GNU’s external growth prospects.

Introduction

South Africa remains one of Africa’s most advanced and diversified economies offering a relatively stable investment environment. Its appeal to foreign investment lies in its world-class financial services, deep capital markets, transparent legal framework and abundant natural resources. Key sectors attracting foreign direct investment (FDI) include manufacturing, mining and financial services. Despite ample investment opportunities, FDI inflows have consistently declined since 2022, dropping from $1.3 billion in the first quarter of 2024 to $965.87 million in the second quarter.

Throughout 2024, South Africa’s economy faced significant disruptions due to persistent electricity shortages, civil unrest and logistical challenges. These factors - coupled with the outcome of national and provincial elections - substantially impacted business confidence, as the South African Chamber of Commerce’s Business Confidence Index (SACCI) declined by 6.9 points over the two months following the May 2024 general election.

The 2024 general elections marked a historic shift in South Africa’s political landscape, as the African National Congress (ANC) lost its 30-year parliamentary majority, securing a record low of 159 seats. This led to the formation of a coalition government, the Government of National Unity (GNU), composed of 10 parties collectively holding 287 of 400 seats (72%) in the National Assembly. The Democratic Alliance (DA), a pro-business party and the main opposition to the ANC, emerged as a key coalition member, securing 87 seats in the National Assembly.

By prioritizing economic growth and a stable business climate, the GNU has gradually bolstered business confidence through its commitment to implement structural economic reforms and enhance public sector performance. The joint initiative between the presidency and the National Treasury dubbed “Operation Vulindlela” aims to transform electricity, water, transport and digital communication infrastructure to promote economic growth and attract foreign investment.

Within six months of the general election, economic growth and investor confidence are gaining momentum, driven by anticipated structural economic adjustments in energy, logistics and the public sector. The South African Reserve Bank reported the first net inflow of capital since 2022, shifting from an outflow of $1.1 billion in Q2 of 2024 to an inflow of $2.1 billion in Q3. This shift reflects renewed investor confidence in the country’s economic stability, as evidenced by increased inflows of direct investments, portfolio investments and reserve assets.

While the business climate shows signs of improvement, the GNU is likely to face multifaceted risks associated with unemployment, poverty and inequality. South Africa’s high unemployment rates - particularly among young people - create profound negative externalities for the state, as the country’s demographic dividend is disproportionately wasted due to a lack of investment in human capital development. Although 22,000 jobs were created in 2024, 137,000 South Africans entered the workforce the same year. The expanded unemployment rate (including discouraged seekers) was 60.8% amongst 15-24 year olds in Q2 of 2024. As unskilled and unemployed working-age adults are consistently delinked from the labour force, a long-term skill gap is latching itself into the employment market. This risks snowballing into a structural unemployment problem whereby individuals lack the skills necessary to bridge the gap toward average employment requirements.

Unrest

South Africa continues to grapple with worsening civil unrest; data illustrates a visible increase in registered protests and riots since 2021. Civil unrest poses significant risks to both the economic and security environment, leading to financial losses, disruption of business operations, and widespread property damage.

Unrest represents an operational hazard for foreign stakeholders and frequent business disruptions continue to damage the GNU’s legitimacy. These trends are likely to persist unless underlying economic issues are effectively addressed.

The July 2021 riots led to $1.5 billion in economic losses and two million jobs being lost or impacted for both local and foreign companies.

Our analysis of historical trends indicates that politicians' failure to appropriately address long-standing unemployment, inequality, and infrastructure deficits have driven grievances and unrest across the country.

Civil unrest remains a key issue obstructing social and economic development in South Africa. South Africa ranked 127 out of 163 on the Institute for Economics and Peace’s (IEP) Global Peace Index 2024, putting it amongst the fifteen most politically unstable countries in Sub-Saharan Africa. Civil unrest increased significantly last year, with 692 protests and riot incidents registered during the first quarter of 2023 compared to 456 over the same period in 2022.

Historically, analysts have associated civil unrest in South Africa with popular resentment towards high and stagnant levels of unemployment and inequality, which are amongst South Africa’s most critical and longstanding socioeconomic challenges. Unemployment increased from 21.8 percent to 28 percent between 2013 and 2023, with the World Bank describing it as “South Africa’s biggest contemporary challenge” in October 2023.

Moreover, South Africa has some of the highest income and wealth inequality levels globally. The population’s richest decile accounts for about 65 percent of national income while the poorest half accounts for 6 percent. Disillusionment towards politicians has historically grown amongst South Africans as governments fail to confront unemployment and inequality, particularly along racial lines.

In July 2021, former South African president Jacob Zuma was arrested in Estcourt, KwaZulu-Natal, after refusing to appear before a judicial commission investigating corruption during his decade in power. Zuma's incarceration led to the violent 'Free Zuma' protests, which escalated and spread to other areas of the country including major cities such as Johannesburg. The riots constituted the largest period of civil unrest since the end of the Apartheid, with an estimated 354 people losing their lives. In our analysis of related data and interviews conducted by local news sources, we assess these protests were largely driven by background economic grievances.

Although the riots in July 2021 were precipitated by Zuma’s arrest, enquiries conducted in the aftermath illustrate that the causes were more deep-rooted. The South African Human Rights Commission (SAHRC) found that high unemployment rates, inequality and poverty were the bedrock from which unrest permeated. Echoing the findings of the SAHRC’s investigation, South Africa’s Minister of Trade, Industry and Competition Ebrahim Patel stated that “while it was true that there were those with a different agenda who lit the match, that match was thrown on dry tinder in communities where there was severe unemployment and poverty”. Further, protests led by the trade union groups Congress of South African Trade Unions (COSATU) and the South African Federation of Trade Unions (SAFTU) over the cost of living and unemployment rates erupted in Pretoria and Cape Town in August 2022, and Johannesburg in July 2023. In late November 2024, residents clashed with police in Johannesburg over a lack of water supply, demonstrating risks of public dissatisfaction with infrastructure deficits.

Previous civil unrest in South Africa has driven security and economic implications that were detrimental enough to shift the risk perceptions of foreign investors and other overseas stakeholders. The ‘Free Zuma’ riots led to $1.5 billion in economic losses and two million jobs being lost or impacted at both local and foreign companies. Unrest primarily disrupts the transportation of goods as major road closures.

Protesters blockaded and damaged key sections of the N2 and N3 highways, significantly disrupting commercial traffic in the KwaZulu-Natal region (KZN) along routes critical to national and regional logistics networks. The closure of these strategic routes constrained commercial cargo traffic and transit freight, disrupting supply chains that link South Africa with landlocked African countries which resulted in significant shortages in food, fuel and medical supplies. In the aftermath, foreign investors cited these riots as a deterrent to new investments and the expansion of existing ones. The economic cost of violence in South Africa as a percentage of GDP amounted to 15.38 percent in 2023.

Assessment:

London Politica assesses that high unemployment and inequality are likely to stagnate or worsen without effective government investments in energy, telecommunication and water supply networks. The absence of effective social investments increases the risk of unrest, particularly in urban areas and neighbourhoods with higher poverty rates. Such unrest is likely to undermine the government’s legitimacy, as constrained economic growth and high unemployment erode support for the GNU’s coalition in favour of populist parties.

The GNU should enact structural reforms to address unemployment, infrastructure deficits, and public sector performance to prevent consequences associated with a declining investment climate. The government’s pledge to address supply-side challenges by boosting investments in electricity infrastructure will likely gradually improve economic productivity and foreign investment in the long term. Although enhanced electricity supply bolstered manufacturing outputs in 2024, persistent social unrest linked to infrastructure deficits remains deeply entrenched and is unlikely to be resolved in the short term.

We assess that disenfranchised South Africans are likely to turn to disruptive demonstrations to voice their grievances against the government’s lack of effective investment. Social unrest will likely continue over the GNU’s term, resulting in occasional infrastructure damage and substantial financial losses to cities and towns across the country.

Crime

South Africa faces high crime rates linked to socio-economic problems which are exacerbated by the ineffective use of resources. Crime and violence divert resources away from development programs, investments in infrastructure and crucial social services as the government focuses instead on immediate security measures.

This misallocation of resources fails to address the root causes of crime and contributes to social inequality. Important sectors like education and economic development are underfunded due to the focus on short-term security.

The problem is cyclical, with short-term security priorities hindering long-term development and prolonging instability.

Crime in South Africa has a very significant impact on foreign investment and capital inflows. Extortion, theft, and violent crime affect the legitimacy of the government and drastically complicate business operations in the country.

South Africa has one of the highest crime rates in the world and continues to see increases in violent crime, including crime that specifically targets businesses. New data put out by the government demonstrates that crime rates have increased since 2021 - coinciding with a decrease in government popularity throughout the same period. Compared to wealthy communities, crime rates in poorer neighbourhoods like Khayelitsha are nearly five times higher, which is indicative of country-wide trends. The significant economic and social issues that residents experience are linked to this disparity. According to research by the Institute for Security Studies, Khayelitsha's high unemployment rate, poor housing conditions, and restricted access to social services all lead to higher crime rates. These circumstances encourage grievances, which can lead people to commit crimes, as illustrated by strong empirical evidence linking economic hardship to higher crime rates in South Africa.

In addition to community-level crime, South Africa is plagued by transnational organised criminal networks that worsen the business environment, slow the economy, and threaten individuals' physical and financial security. According to the Organised Crime Index, South Africa ranks 3rd as the African country most affected by organized crime, based on the prevalence of criminal activity and the ineffectiveness of state responses to counteract it. Transnational organized crime is defined as illegal activities carried out across borders by structured networks such as gangs, drug trafficking syndicates and international criminal networks. The most prevalent criminal markets in South Africa are human trafficking, financial crimes and arms trafficking. Throughout 2024 the South African Police Service dismantled 30 illegal drug laboratories and seized over $18 million worth of illegal drugs.

The prevalence of organised crime is deeply rooted in corruption within government and police forces and is worsened by a lack of cooperation between institutions. Because a large number of politicians and bureaucrats benefit from corrupt relationships with criminal organizations, they hold a vested interest in impeding efforts to combat it. Government officials are frequently compensated to overlook illicit actions once they are uncovered and to provide details on police operations and strategies to combat criminal activities. Despite government strategies implemented to combat organised crime, a lack of institutional cooperation and corruption among government and police forces have hindered their efforts.

There are substantial geopolitical and economic implications of South Africa's internal instability and high crime rate. The country's failure to uphold internal security harms its standing as a regional and international leader, complicating its efforts to project influence and collaborate on international projects through its G20 presidency.

High crime rates - and high rates of extortion specifically - significantly discourage foreign investment; foreign investors have refrained from entering the South African market due to costs associated with crime, including security measures and insurance premiums. Furthermore, a World Bank study from 2023 on South Africa's investment climate notes that a decline in FDI has been observed in industries such as tourism and manufacturing due to safety concerns and high crime rates.

The South African government has attempted to implement several policies to lower crime rates. Crime reduction is a major goal of initiatives such as the National Development Plan (NDP) 2030. Strategies to achieve this goal focus on strengthening law enforcement, improving the justice system, and addressing the socioeconomic drivers of crime. These efforts are complemented by increased funding for the South African Police Service (SAPS) and the adoption of community policing techniques. Unfortunately, corruption, low funding, and the absence of institutional collaboration have frequently impeded these attempts. The overall influence on national crime levels has been minimal, notwithstanding localised successes in certain urban districts. A recent Gallup poll indicated that South Africa ranks among the top three countries in which people feel the least safe walking alone at night. This suggests that more comprehensive strategies are required that address the underlying socio-economic problems that drive crime, in addition to improving law enforcement capabilities.

Assessment:

We assess that insufficient investment in social development, coupled with the failure to address corruption linking the state to transnational criminal networks, is likely to exacerbate existing disparities between communities. This will likely place additional strain on the state’s resources, given the government’s inevitable investment in policing and short-term security expenditures. Rising crime rates driven by unrestrained poverty and inequality will likely fuel growing social unrest and continue to erode public trust in state institutions.

Pessimism concerning South Africa’s investment climate will likely continue to harm the government’s popularity and legitimacy. Limited economic growth worsens already-existing social inequalities, further inhibiting economic progress, and restricting the creation of new jobs. The risk of increasingly frequent and violent civil unrest will likely deter foreign companies from operating in the country, further restricting FDI flows and directly constraining economic growth.

We assess that heightened levels of social unrest are likely to compel the government to divert substantial resources toward security and reconstruction efforts, further constraining funding for investments targeting poverty, inequality, and unemployment. Effective investments targeting structural economic adjustments and socially focused projects will likely benefit the GNU’s expenditures in the long term.

Populism

Right and left-wing populism is on the rise in South Africa. The ANC dropped from a 70% vote share in 2004 to 40.2% in the 2024 general elections. In the same election, populist parties uMkhonto weSizwe (MK) and Economic Freedom Fighters (EFF) respectively gained 14.6% and 9.5% of the vote share.

The rise of populism in South Africa can in part be explained by high voter discontent for the longstanding ruling party, the ANC. Persistent economic challenges that disproportionately impact less educated and economically disadvantaged segments of the population are likely to continue to drive these groups to support populist parties.

Continued failure to address long-standing economic grievances by the government is likely to lead to the further delegitimization of the GNU, threatening its coalition and leading to increased support for populist parties.

Increases in support for populist parties can be particularly observed in rural areas, which have high levels of voter discontent due to regional economic disparities. Rural areas tend to suffer more economically. As of 2017, poverty rates in rural areas (81.3%) were about double those in urban areas (40.7%). Poverty in rural areas has been exacerbated by the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic, the national hunger crisis, as well as continuous load shedding.

For instance, the largely rural province of Kwazulu-Natal had the highest share of votes for populist parties of all provinces in the 2024 election. Zuma’s populist party MK received 45.3% of Kwazulu-Natal’s votes. Kwazulu-Natal also has the second-highest number of people living in poverty. In Gauteng - an urban, comparatively wealthy province that makes up roughly 33% of GDP and has the highest provincial GDP per capita - voters largely backed the ANC.

Simultaneously, lower voter turnout rates can be more broadly observed in provinces that have higher GDP per capita, with the exceptions of Gauteng and the Western Cape. Moreover, voter turnout in the 2024 elections reached a historic low of 58.6% (in comparison to 89.3% in 1999). This could be indicative of a wider trend in which voter fatigue has driven lower turnouts in ANC strongholds and stronger turnouts in regions where populist parties have wider support.

Assessment:

We assess populist parties are likely to continue to mobilise poorer segments of the population to cast protest votes against the perceived status quo. Additionally, growing disillusionment with the ANC-led coalition will likely lead to further increases in voter abstention among former ANC supporters, reflecting a deepening erosion of confidence in the government. This trend is underscored by the historically low voter turnout observed in the 2024 elections.

This trend is likely to be exacerbated by the rhetoric of populist parties, which particularly target poorer and predominantly ethnically black communities. In the long term, there is a reasonable possibility that this will result in a significant shift in vote distribution, further weakening the ANC and posing a threat to the GNU.

This trend is likely to persist in both future regional and national elections unless the GNU’s policies effectively address the needs of disenfranchised communities. Such measures must include structural economic reforms and effective investments in education, infrastructure, social programs, and poverty alleviation initiatives at the local level.

Sahelian Security Tracker - Chad

Executive Summary

TLDR: Chad is likely to remain generally politically stable over the next 6 months; large-scale protests are unlikely and rebel groups are unlikely to effectively challenge the government.

Intercommunal tensions in the east exacerbated by refugee flows from Sudan are unlikely to result in large-scale conflict in the short term, although isolated incidents of ethnic/intercommunal violence remain possible.

Although there may be a small terrorist presence in Southwestern Chad, it is unlikely that terror groups will gain any territory in the country in the short to medium term. Attacks on N’Djamena or major population centres remain unlikely, while there is a reasonable possibility that terrorists may conduct attacks in the Lac region in the short term.

The threat posed by criminal groups in the south/southwest is also unlikely to be abated over the short to medium term.

*The yellow icons indicate locations that are more likely to see protests in the event of domestic unrest, and we did not include communal violence as it is an omnipresent risk in nearly every region of Chad.

Introduction

Chad currently faces many security challenges, exacerbated by the war in Sudan and the proliferation of terrorism across the Sahel. Although conflict in Sudan’s Darfur region has not yet extended into Eastern Chad, continued migrant flows risk increasing communal tensions between farmers and herders over natural resources, a risk that is worsened by weapons smuggling and the presence of armed groups that have previously engaged in ethnic conflict. In Chad’s southwest, military campaigns and tensions between jihadist groups over the last year have largely mitigated the threat of direct terrorist action in Chad, but the threat posed by terror groups persists. In the south/southwest, criminal groups continue to carry out kidnappings for ransom with near impunity.

Further, the first half of 2023 saw a 150% increase in inter and intra-communal violence in Chad compared to the first half of 2022, the vast majority of which was concentrated in the south, near the border with the Central African Republic. This occurs amidst a backdrop of political instability - protests over the last several years have left hundreds dead and rebel groups in the far north have officially renewed their campaigns against the government. Even so, in December Chad’s transitional government, led by Mahamat Déby, reached an agreement with the largest opposition party, likely quelling the immediate threat of large-scale instability. Elections are scheduled for November 2024.

Refugee Crisis in the East

Security-related developments in Eastern Chad are largely dependent on events in neighbouring Sudan. So far, the war in Sudan has driven at least 500,000 civilians into the eastern Chadian provinces of Ouaddaï, Sila, Wadi Fira, and Ennedi-Est. According to the UN, this is adding to pre-existing socioeconomic pressures in the region. Temporary camps remain erected on lands previously used for farming and herding, which has exacerbated the shortage of basic resources that has previously driven violence between ethnic groups.

Largely because of the conflict in Sudan, in which Arab armed groups - principally the Rapid Support Forces (RSF) - with ties to the Darfur genocide have committed ethnic violence against Black African communities, mistrust remains prevalent between Black African and Arab ethnic groups in Eastern Chad. Although some analysts hold that the RSF may follow Black Africans into Chad and commit atrocities, we assess that this is very unlikely to be carried out systematically in the short term as the focus of the group’s leadership remains on taking control of Sudan and garnering global legitimacy.

According to the International Crisis Group, Arab refugees in Eastern Chad feel unfairly associated with the actions of the RSF as NGOs have given first priority to Black African refugees, and as Arabs are suspected of sending their sons to fight with the RSF. In this context, it remains unlikely but possible that NGOs may face direct attacks by disconcerted Arabs or armed groups. In our review of local media sources and social media, we have not identified any episodes of ethnic or communal violence in Eastern Chad since the start of the war in Sudan. We have however identified incidents of purported abuses at the hands of the Chadian security forces as they crack down on weapons smuggling to abate communal conflict.

The presence of weapons indicates that groups or individuals would have the capability to commit mass violence but so far lack the intent to do so. This may change as the war in Sudan continues, more refugees pour into Chad, and resource scarcity becomes more acute. Regardless, we maintain that large-scale violence remains unlikely in the short term as the Chadian government is heavily incentivised to remain uninvolved in the conflict in Sudan; Déby’s transitional government is dependent on support from Black African and Arab elements, neither of which support the RSF (a group that several news outfits suggest Déby is allowing the UAE to aid via Chad). Additionally, large Chadian troop deployments in the east are likely to mitigate the risk of large-scale communal violence. Given past precedent, incidences of ethnic violence are most likely to occur in Ouaddaï.

General Political Stability

Over the last few years, there have been a number of large-scale protests and violent responses from security forces, particularly in N’Djamena. These protests were driven by a perceived power grab by current President Mahamat Déby after the death of his father, President Idriss Déby, in clashes with Front pour l’alternance et la concorde au Tchad (FACT) in the north. Although some opposition parties boycotted the recent agreement between the ruling Mouvement Patriotique du Salut and the opposition Les Transformateurs, the agreement has largely mitigated the threat of instability in the short term by bringing a number of stakeholders into the fold. The government has also pardoned the vast majority of protesters who had previously been arrested.

Despite this, according to an expert we spoke to for this assessment, much of the Chadian public remains disillusioned with the government, few of which turned up to vote in the constitutional referendum in December. This expert believes the official voter turnout number was falsely inflated and that unrest after or in the run-up to the November elections is likely. We maintain that, in the event of unrest, future demonstrations are most likely to occur in large population centres in the south/southwest of the country, and would likely pose incidental risk to foreign companies and NGOs, and may pose a direct risk to those that have easily identifiable ties to the west. Previously, the largest protests took place in Chad’s two most populous cities, N'Djamena and Moundou. Other southern cities such as Doba, Bébédjia, and Koumra have also seen a number of demonstrations.

In the past week, Mahamat Déby travelled to Moscow to meet with Vladimir Putin, signalling closer security cooperation between the two governments. Putin praised Déby for holding the December referendum and pledged the Kremlin’s support for further stabilising the country. The private aircraft on which Déby travelled to Moscow belongs to the same Emirati company that has shuttled RSF leader Hemedti to meetings with neighbouring leaders. We hold that closer security cooperation between the Kremlin and N'Djamena and the departure of French troops make large-scale demonstrations less likely in the short to medium term.

Chad remains in recurring conflict with rebels in the gold-rich northern Tibesti province; various factions based in southern-Libya continue to engage in skirmishes with Chadian security forces. In June 2023, the army halted an incursion of the Front national pour la démocratie et la justice au Tchad and Conseil de commandement militaire pour le salut de la République rebel groups in the Kouri Bougoudi region, home to Chad’s largest goldfield. Some rebel groups are also active in Sudan, fighting alongside the RSF. This may allow the rebels to gain a stronger footing in Sudan, making it more difficult to uproot them, especially given Mahamat Déby’s public neutrality in the conflict. Even though it is unlikely that the Chadian government will succeed in fully defeating various rebel groups, they will unlikely pose a serious threat to the stability of the country in the short to medium term. However, as the November elections approach, rebel groups may see more popular support within the country, emboldening them further.

Insecurity in the South / Southwest

The largest source of insecurity in Southern Chad is the proliferation of violent crime, in particular kidnappings for ransom. Local media sources report that criminals are responsible for a string of kidnappings, especially in the Mayo-Kebbi Est and Mayo-Kebbi Ouest border regions with Cameroon. Kidnappings are also increasing in N’Djamena. Victims include farmers and students, and recent evidence suggests that criminals are operating across borders. Criminal or armed groups have not yet targeted NGO workers and foreign business people, but high rates of persistent criminality and impunity suggest they face increased levels of incidental risk. They may be directly targeted in the near future given the perceived resources at their disposal. Even though the government is ramping up its response to criminal groups, we foresee a continued heightened kidnapping risk over the short to medium term. There is also a risk that criminal organisations have or will collaborate with terror groups in Chad, as they have in Nigeria, which would likely increase their capabilities.

The Lake Chad region, covering parts of Cameroon, Niger, Nigeria, and Chad is a hotbed of terrorist activity, and is a stronghold for Boko Haram and the Islamic State – West Africa (ISWAP); however, conflict between the two and factional infighting has weakened them. The continued security response by the Chadian army - buttressed by material support from the UAE - and the Multinational Joint Task Force (MNJTF), have diminished the jihadists' capability to carry out attacks.

There have been reports of terror attacks in very close proximity to the Cameroon/Chad border. The jihadists’ ability to move in small groups to attack villages and civilian targets, especially in the border region, is unlikely to be subdued by the government’s security response in the short to medium term. Past precedent around attacks in Chad indicate that terror groups are more likely to target Chadian soldiers than civilians, and present the largest threat in the Lac region, where a large number of humanitarian organisations operate. These groups present an existing threat in the rest of the border regions with Cameroon and Nigeria, including in N’Djamena.

The south of the country has also recently seen a sharp uptick in communal tensions resulting in violence. In May, a herder-farmer dispute in the Mandoul province led to the deaths of 9 people, including a child. Earlier that month armed “bandits” slaughtered 11 farmers in a neighbouring region. The UN OCHA reported 30 incidents of communal violence in the south during the first half of 2023 alone. Conflict over scarce resources is likely to drive further inter-communal violence. NGOs and IGOs have so far been unaffected by the local tensions and outbreaks of violence, but there is a large presence of humanitarian organisations in the south that may face incidental risk and may be targeted if they are perceived as providing assistance along communal lines.

Sahelian Security Tracker - Mali, Burkina Faso, and Niger

Welcome to the Africa Desk SST, where we aim to provide granular insights for companies, organisations, or individuals operating or travelling in the central-western Sahel and/or Gulf of Guinea using intelligence techniques. If you are interested in more tailored insights, contact us at externalrelations@londonpolitica.com.

Burkina Faso

If you would like to see a more comprehensive overview of events in Burkina Faso, see the first edition of our SST here.

Based on the information we have collected since the last edition of the SST, terrorist violence in Burkina Faso continues to proliferate across the country, with the northern regions (Centre-nord in particular) bearing the brunt of terrorist activity. Attacks against civilians and combatants are continuing at a rapid pace, occurring frequently in the country’s north, west, east, and southeast. Attacks are also becoming more common in Centre-ouest, a region in close proximity to the capital, Ouagadougou.

The country also finds itself in the midst of an intense battle with a dengue fever outbreak that is currently most pronounced in Ouagadougou and Bobo Dioulasso, Hauts-Bassins region. So far, over 73,000 cases have been registered in the country, although the true number is likely far higher. International organisations including UNICEF and the International Rescue Committee (IRC) are working to train doctors to handle dengue in Hauts-Bassins, deliver clean water, improve sanitation, and provide healthcare services. Several regions in the north have been entirely cut off from aid due to terrorist activity.

Recent Developments

9 October - JNIM (Jama’at Nusrat al-Islam wal-Muslimin) claims via their Al-Zallaqa media channel that they set off an explosive device against elements of FABF in Séguénéga, Northern Burkina Faso, killing several.

11 October - JNIM attacked the Volantaires pour la défense de la patrie (VDP) - a volunteer defence unit that works alongside FABF (Forces Armées du Burkina Faso) and the national police - and the national police at their camp in Yamba, Eastern Burkina Faso, killing at least 20.

11-12 October - FABF claims to have acquired intelligence pertaining to a JNIM attack in Sitgo, Séguénéga. They claim to have launched subsequent airstrikes against JNIM in the staging area which were aided by ground forces.

12 October - JNIM claims to have attacked FABF in Banwali, Hauts-Bassins. They claim to have acquired heavy weaponry in the assault.

16 October - According to FABF, JNIM attacked FABF and VDP positions near Tikaré, Bam, Centre-nord. FABF says they launched air strikes against the militants as they fled north after the attack.

18 October - The government of the Centre-nord state extended a ban on certain models of motorbikes that are commonly utilised by JNIM militants.

18 October - According to FABF, they carried out airstrikes against JNIM militants in Zoura, Centre-nord, who had attacked a VDP position in Sian, Centre-nord. They also claim to have killed militants in airstrikes in Silgadji, Soum, Sahel region.

19 October - According to local media sources, JNIM carried out an attack on a primary school in Zawara, Sanguié. This represents a rare attack in the Centre-ouest region and was the first attack in Zawara.

Operational Forecast

We maintain that it is unlikely that FABF will be able to effectively abate JNIM attacks across the majority of Burkinabe territory over the next 6 months and it is unlikely that FABF will take significant territory back from JNIM in the same time period.

We maintain that it is likely that JNIM will continue to carry out attacks in increasingly close proximity to Ouagadougou, within the regions of Centre-ouest and Plateau Central, and it is likely they will attempt to carry out an attack in Ouagadougou over the next 6 months.

Since our forecast last week, JNIM attacked a primary school in Centre-ouest.

Although Ouagadougou is likely to remain generally stable over the next 3 months, there is a reasonable possibility that JNIM will attempt to capture Ouagadougou within the next year in the absence of adequate international assistance.

Flights to and from Ouagadougou are unlikely to be significantly impacted by conflict over the next 3 months.

It is likely that the efforts of NGOs and IGOs to address the dengue outbreak, particularly in the Hauts-Bassins region, will be directly impacted by the proliferation of terror groups.

These groups, including the IRC, are almost certain to continue to face supply chain difficulties across the country, particularly in Djibo, the hub of IRC operations in Burkina Faso.

NGOs and IGOs are increasingly likely to become direct targets for property theft or violent attacks by terror groups as the groups proliferate.

Niger

If you would like to see a more comprehensive overview of events in Niger, see the first edition of our SST here.

Niger continues to see terrorist-related violence across the country’s southwest, in Tillabéri department in particular. Levels of violence remain slightly elevated from pre-coup levels but significantly lower than in Mali or Burkina Faso. However, the attacks that do occur are occurring in closer proximity to the capital, Niamey, sustaining risks to global businesses and large population centres. NGOs that operate across Tillabéri, including the Danish Refugee Council (DRC), are at a uniquely heightened risk of being affected by terrorist violence. Supply chain issues with the transfer of humanitarian supplies are likely to be exacerbated and increasing displacement as a result of the conflict is likely to further strain NGO resources.

Recent Developments

9 October - The French military begins formal withdrawal from Niger.

15 October - Burkinabe journalist reports that JNIM is enforcing a blockade on the village of Tamou, Tillabéri department, (100km south of Niamey) and is asking populations of nearby villages to leave. We have not been able to independently verify this claim.

15 October - A local journalist reports that terrorists ambushed FAN between Teguéy and Téra, Tillabéri, killing at least 2. We have not been able to independently verify this claim.

15 & 16 October - FAN (Forces Armées Nigeriennes) clashed with militants over a two day period in Lendou, Tillabéri. FAN claims that 31 terrorists were killed alongside 6 Nigerien soldiers.

17 October - Social media accounts claim that ISGS (The Islamic State in the Greater Sahara) invaded the villages of Toukounous and Garin Guiye, northeast of Niamey. We have not been able to independently verify this claim.

19 October - The Nigerien government reports that deposed ex-president Mohamed Bazoun attempted to escape military custody and leave the country. The government says it foiled the attempt.

22 October - The French military completed its withdrawal from its camp in Ouallam, Tillabéri (roughly 100km north of Niamey), handing it over to FAN. 475 French soldiers have departed the country since 20 October.

Operational Forecast

We maintain that it is likely that ISGS and JNIM will continue to carry out attacks and consolidate more territory in southwest Niger, in Tillabéri and Téra departments in particular. Intelligence gaps created by the ongoing withdrawal of the French and an under-resourced FAN will make it challenging to address the growing terror threat.

Barring the implementation of mitigating factors, such as a holistic plan to address terror or security/intelligence agreements with foreign partners (the latter looks unlikely since the coup), there is a reasonable possibility that terror groups may pose a threat to Niamey within the next 6 months.

FAN is likely to remain in control of Niamey over the next 6 months, but there is a reasonable possibility that ISGS will attempt an attack in Niamey in the same time period.

Flights to and from Niamey are unlikely to be affected by terrorist violence in the next 3 months.

We maintain that it is very unlikely that terror groups in Niger’s southeast will pose a significant threat to the Nigerien state, or to large businesses and organisations, over the next 6 months.

We maintain that uranium mines in the north, near the city of Arlit, that are majority owned by the Orana group, are very unlikely to be affected by terrorist violence over the next 6 months, however supply chain complications resulting from an increase in violence in the south may increase costs for companies.

The Orana Group may also face local reputational challenges and resulting security threats stemming from its ties to the French Government.

We maintain that gold mining projects in the country’s southwest, including the Samira Hill Gold Mine in Téra, are likely to be directly impacted by terrorist violence in the next 6 months. Terror groups may directly target the mines to add to their illicit mining operations.

NGOs are very likely to continue to face heightened operational challenges across the country’s southwest as a result of terror proliferation.

The DRC’s operations in Tillabéri are almost certain to be continuously affected, and NGOs in the region may be targeted in attacks.

Although the DRC’s operations in Dosso (roughly 140km southeast of Niamey) are unlikely to be significantly impacted in the next 3 months, there is an increasing likelihood that they may be impacted in the medium term.

Mali

If you would like to see a more comprehensive overview of events in Mali, see the first edition of our SST here.

As the UN mission in Mali (MINUSMA) continues its withdrawal, the security situation across Northern and Central Mali continues to deteriorate. JNIM has continued its attacks on FAMa (Forces Armées Maliennes) elements, as well as on UN convoys, underscoring the heightened risk faced by the UN and international organisations in Northern and Central Mali. A spokesman of the CSP (Cadre Stratégique Permanent), a consortium of Tuareg rebel groups, has claimed the CSP will stop FAMa from retaking Northern Mali. According to several Tuareg-run media sources, FAMa and Wagner have committed significant human rights abuses amid offensives over the last two weeks, including the killing of civilians.

JNIM is currently attempting to enforce a complete blockade on Timbuktu and Gao, the two largest cities in the north, causing shortages of fuel, food, and medicine; a Gao resident who spoke to the BBC says fuel shortages are causing blackouts. All flights to and from Gao have been grounded. These developments sustain and heighten supply chain risks across the immediate region - this is particularly relevant to businesses in Niger, who share significant trade relationships with businesses in the Gao region of Mali.

Recent Developments

*When referring to FAMa announcements, we put the word ‘terrorists’ in parentheses because FAMa refers to both the CSP, as well as JNIM and ISGS as terrorists.

13 October - JNIM ambushes FAMa in Konna Boré, Central Mali, killing 17 and destroying and seizing vehicles.

15 October - JNIM announces via their Al-Zallaqa channel that they attacked FAMa with an IED between Gao and Anefis, Northern Mali, on 15 October. They also announced they had fired on a UN cargo plane in Tessalit, which was confirmed by FAMa.

17 & 18 October - FAMa announces that they launched counteroffensives on ‘terrorists’ near Tessalit, and conducted airstrikes on convoys in Tessalit and Kidal.

18 October - JNIM announces that they attacked FAMa near Diangassagou, Central Mali, destroying cars and ammunition, and that they burned over 40 UN peacekeeper trucks in Kuna, Mopti, Central Mali.

19 October - According to the UN, another UN plane landing in Tessalit was fired upon.

21 October - MINUSMA completes withdrawal from Tessalit camp, Northern Mali. According to the UN, they completed their withdrawal from Tessalit ahead of schedule due to an “extremely tense and degraded security context.”

22 October - MINUSMA completes withdrawal from Aguelhok camp, Northern Mali, and Douentza camp, Central Mali.

23 October - FAMa announces that ‘terrorists’ raided the Aguelhok camp after the UN withdrawal. FAMa also stated that the UN retreat threatens the security of the Aguelhok region and that FAMa remains in possession of the Tessalit and Anefis camps recently abandoned by the UN..

25 October - JNIM claims they undertook an IED attack on a FAMa and Wagner convoy between Hombori and Gossi, Northern Mali, killing all passengers.

26 October - The UN announces that a UN logistics convoy travelling from Ansongo to Labbezanga, Gao, Northern Mali, was fired upon by 4 assailants. One driver was seriously injured.

Operational Forecast

It is likely that the security situation across Central and Northern Mali will continue to deteriorate as more peacekeepers continue to withdraw.

Given FAMa and Wagner’s apparent inability to hold territory in the country’s centre - even as they undertake offensives to the north - we continue to assess that it is likely that terror groups will continue to carry out persistent attacks in Central Mali mostly unabated, and also that these groups are likely to continue to slowly expand southwest towards Bamako.

Since our last forecast, JNIM has undertaken several attacks on FAMa in Central Mali.

We continue to assess that it is very unlikely that flights to and from Timbuktu will resume in the next 3 months, and very unlikely that we will see an increase in flights to and from Gao in the next 3 months. Flights to and from Gao airport have been suspended as JNIM attempts to blockade the city.

We maintain that Bamako is likely to remain generally stable over the next 3 months, but there is a reasonable possibility that JNIM may attempt to carry out a large-scale attack there in the next 6 months to a year. In the next 6 months to a year, JNIM may attempt to take Bamako.

It is likely that UN personnel and assets will continue to come under threat in Northern Mali as a means to expedite the group’s exit from the country. There is a reasonable possibility that international organisations - principally NGOs that are active in Central Mali - may also face attacks from JNIM in the short-medium term.

Sahelian Security Tracker - Mali, Burkina Faso, and Niger

Welcome to the Africa Desk SST, where we aim to provide bi-weekly, granular insights for companies, organisations, or individuals operating or travelling in the central-western Sahel and/or Gulf of Guinea using intelligence techniques. If you are interested in more tailored insights, contact us at externalrelations@londonpolitica.com.

Overview

Over the last several years various coups have rocked Sahelian Africa - the central-western Sahel in particular. Coups in Mali in 2020 and 2021, in Burkina Faso in January 2022 and September 2022, and in Niger in 2023 have had and will continue to have security implications for governments, international ogranisations, NGOs, and businesses. Since the respective coups in Mali and Burkina Faso, it is undeniable that the security situation in both countries has continued to worsen.

In Mali, the government and Russian private military contractor Wagner are battling Tuareg separatist groups in the north, as well as terror groups Jama’at Nusrat al-Islam wal-Muslimin (JNIM) in Central Mali and The Islamic State in the Greater Sahara (ISGS) in the east. London Politica research indicates that the government is unlikely to be able to recapture and hold large portions of land in the country’s north, centre, or east in the short to medium term.

In Burkina Faso, terror groups JNIM and ISGS have continued to ramp up attacks and now have a significant presence in all regions apart from Centre-Ouest, Centre-Sud, Centre (Ouagadougou, the capital), and Plateau-Central. While there has not been a large-scale terror attack in the capital since 2018, we assess that - in the absence of significant foreign security assistance and/or a holistic counter-terrorism strategy - it is likely that JNIM will carry out an attack in Ouagadougou in the next year.

In Niger, in the two months since the coup ISGS activity has significantly increased. Terrorist activity is largely concentrated in the country’s southwest, and attacks have grown bolder, more frequent, and have occurred closer to the capital, Niamey, since the coup.

JNIM’s tentacles have also extended into Benin, Ivory Coast, Togo, and Ghana within the last year, where terrorists have committed attacks and others have been identified and arrested by local authorities. We will cover these countries in future editions of the SST.

Mali

According to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED), Mali has seen a 38% increase in political violence from last year, almost all of which can be attributed to terror groups (principally JNIM but also ISGS), the Forces Armées Maliennes (FAMa), and the Wagner group. JNIM has carried out attacks and, alongside the Cadre Stratégique Permanent (CSP), a loose consortium of Tuareg separatist groups, taken territory throughout the centre and north of the country, including several army bases. JNIM is currently maintaining a blockade around Timbuktu, the most populous city in the country’s north, and is not letting any goods in and out of the city.

In September JNIM and FAMa had a large battle in the Timbuktu region, leaving roughly 60 dead. JNIM holds a significant amount of territory in Central Mali and has recently committed repeated attacks in and around Mopti and Segou - the latter is roughly 230km from Bamako.

JNIM and ISGS have also been wreaking havoc as of late in the country’s east, in and around Gao, from which the ISGS has fanned out into Southwestern Niger. Given there is very little evidence of clashes between JNIM, ISGS, and the CSP, it is feasible to assume that the groups are - at the very least - working in cooperation with one another. Dragonfly Intelligence anticipates that over the coming months it is highly likely that the Malian Government will “lose control of large parts of their territory.”

Further, London Politica has spotted a Tunisian Air Force plane that has been making recurring trips from Bamako to and from an unknown destination in the country’s north over the last week. This may indicate that Tunisia is offering, or planning to offer some sort of military assistance.

Recent Developments

*When referring to FAMa announcements, we put the word ‘terrorists’ in parentheses because FAMa refers to both the CSP, as well as JNIM and ISGS, as terrorists.

27 September - JNIM announces via their Al-Zallaqa media channel that they attacked FAMa in Acharane, a village 35km west of Timbuktu, showing off a wealth of military gear and trucks commandeered from FAMa. FAMa announced that they repelled the attack successfully and a local news source posted a video of the encounter that we have not been able to verify.

28 September - FAMa announces that ‘terrorists’ attacked an army camp in Dioura, in Central Mali. They reported to have repelled the attack, killing roughly 50 militants. A spokesperson for CSP told Africanews that it had captured the camp.

1 October - FAMa reports that there was intense fighting between them and ‘terrorists’ in Bamba, just under 200km east of Timbuktu. A video (WARNING - SENSITIVE CONTENT) published by an independent journalist purports to show CSP fighters celebrating the capturing of the camp.

2 October - A FAMa convoy departed Gao to head north towards Tessalit, Aguelhok, and Kidal, which are CSP strongholds. A Tuareg news agency reported that the convoy split into three smaller convoys, one heading to the north, another to the east, and one towards Enviv, in the far north.

3 & 4 October - FAMa reports that there was an attack on their convoys in Almoustrat, Northern Mali and Nampala, Central Mali on 3 October, and an attack on a dam in Taoussa, Northern Mali on 4 October. Further, a CSP spokesperson told Reuters that they seized the FAMa army camp in Taoussa, roughly 250km east of Timbuktu, on 4 October.

5 October - FAMa claims in a communique that ‘terrorists’ failed to stop their advance to the north, 10km south of Anefis, Northern Mali.

6 October - CSP militants post a video claiming the army has made no progress towards Enviv. On the same day FAMa announced they repelled an attack in Nyiminyama, Central Mali.

7 October - CSP claims it is being bombarded by FAMa strikes as they were attempting to encircle Enviv, Northern Mali.

7 & 9 October - a CSP commander (WARNING - SENSITIVE CONTENT) and local journalist claim that FAMa and Wagner have committed persistent atrocities over the last week in their offensive towards the country’s North. Although we cannot verify the video, these atrocities are in line with previous acts committed recently by FAMa and Wagner in other parts of Mali.

Operational Forecast

Given FAMa and Wagner’s apparent inability to hold territory in the country’s centre - even as they undertake offensives to the north - as well as the persistent increase in terror attacks in the area, we assess that it is likely that terror groups will continue to carry out persistent attacks in Central Mali mostly unabated, and also that these groups are likely to continue to slowly expand southwest towards Bamako.

It is likely that terror groups will remain prominent in Mali in the long term - a crumbling economy that offers scarce opportunities, as well as the need for protection brought on by atrocities at the hands of all parties will very likely drive more people into armed groups.

It is very unlikely that flights to and from Timbuktu will resume in the next 3 months, and unlikely that we will see an increase in flights to and from Gao in the next 3 months. Gao Airport is currently hosting roughly 2-4 flights to and from Bamako weekly.

Gold mines in Mali’s southwest are very unlikely to be affected by conflict in the next 6 months, but the further expansion of armed groups may complicate supply chains and increase costs for mining companies.

Bamako is likely to remain generally stable over the next 3 months, but there is a reasonable possibility that JNIM may attempt to carry out a large-scale attack there in the near future. In the next 6 months to a year, there is a reasonable possibility that JNIM will attempt to take Bamako.

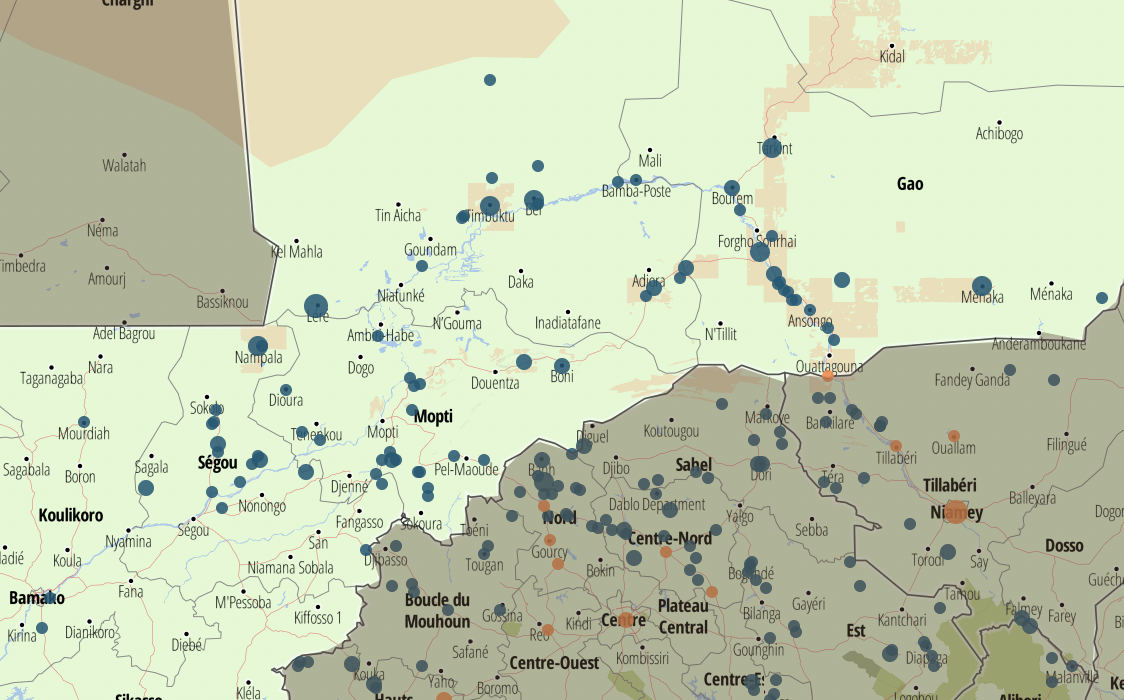

The above image depicts notable security-related events identified by London Politica in Northern Mali since 27 September, 2023.

The above image depicts all identified incidents of political violence (blue) and protests (orange) that occurred in Mali in September. Source: ACLED

Niger

According to ACLED, there has been a 42% increase in political violence in Niger (only part of which is made up by terrorist violence) in the month since the July coup, accompanied by a 300% increase in ISGS activity. Despite the recent uptick, Niger still experiences low levels of terrorism related violence compared to Mali and Burkina Faso. Most terrorist violence in Niger occurs in the country’s southwest, being most heavily concentrated in the region of Tillabéri, in relatively close proximity to the capital, Niamey. Because of the region’s close proximity to areas of Mali and Burkina Faso that are overrun by terrorists, it is prone to spillovers. This complicates matters for Niger as the attacks that do occur have largely been undertaken nearer to densely populated areas than in Mali.

After the coup, a news channel friendly to ISGS said that it would “create favourable conditions for militants,” which is an indication that groups may be emboldened by the coup and subsequent departure of French troops. However some analysts, including Fahiraman Rodrigue Koné, the Sahel Project Manager at the Institute for Security Studies (ISS), conclude that the Forces Armées Nigeriennes (FAN) are better prepared to react to insurgencies than Mali or Burkina Faso. Previous to the coup, Niger was renowned for its successful strategy in abating terror, which coupled security efforts with socioeconomic policy.

FAN are also contending with lower level Boko Haram and Islamic State West Africa (ISWS) insurgencies in the country’s desolate southeast. Levels of violence in the southeast have sharply declined over the last month.

Recent Developments

28 September - A local news source reports that terrorists (very likely ISGS) killed at least 10 FAN soldiers in Kandadji, Tillabéri (190km northwest of Niamey). Other sources claim up to 22 dead.

1 October - Local news sources claim ISGS ambushed FAN 4km north of Malian border, killing 33.

3 October - The Nigerien Ministry of Defence announces that over 100 ISGS militants attacked FAN near the border with Mali, northwest of Tabatol, killing 29.

5 October - FAN General Mohamed Toumba states in a press conference that "Terrorists are more armed than our soldiers, they have weapons that our states don't have plus they have cash."

8 October - FAN announces that terrorists raided Bégorou tondo, Tera department (roughly 190km northwest of Niamey) on 7 October, killing 7 civilians.

8 October - Nigerian news source announces that terrorists attacked the Banibangou police station on the night of 7 October, roughly 250km north of Niamey.

8 October - Nigerian news source announces an attack on Bibiyergou, roughly 115km northwest of Niamey, leaving 3 civilians dead.

Operational Forecast

It is likely that ISGS will continue to carry out persistent attacks and consolidate more territory in southwest Niger, in Tillabéry and Tera departments in particular. Intelligence gaps created by the recent departure of the French and an under-resourced FAN will make it challenging to address the growing terror threat.

Barring the implementation of mitigating factors, such as a holistic plan to address terror or security/intelligence agreements with foreign partners (the latter looks unlikely since the coup), ISGS is likely to pose a threat to Niamey within the next 6 months.

FAN is likely to remain in control of Niamey over the next 6 months, but it is likely that ISGS will attempt an attack in Niamey in the same time period.

Flights to and from Niamey are unlikely to be affected by terrorist violence in the next 3 months.

It is very unlikely that terror groups in Niger’s southeast will pose a significant threat to the Nigerien government, or to large population centres over the next 6 months.

Uranium mines in the north of Niger, near the city of Arlit, that are majority owned by the Orano group, a French company, are very unlikely to be affected by terrorist violence over the next 6 months, however supply chain complications resulting from an increase in violence in the south may increase costs for companies.

The Orano Group may also face local reputational challenges and resulting security threats stemming from its ties to the French Government.

Gold mining projects in the country’s southwest, including the Samira Hill Gold Mine in Tera, are likely to be directly impacted by terrorist violence in the next 6 months. Terror groups may directly target the mines to add to their illicit mining operations.

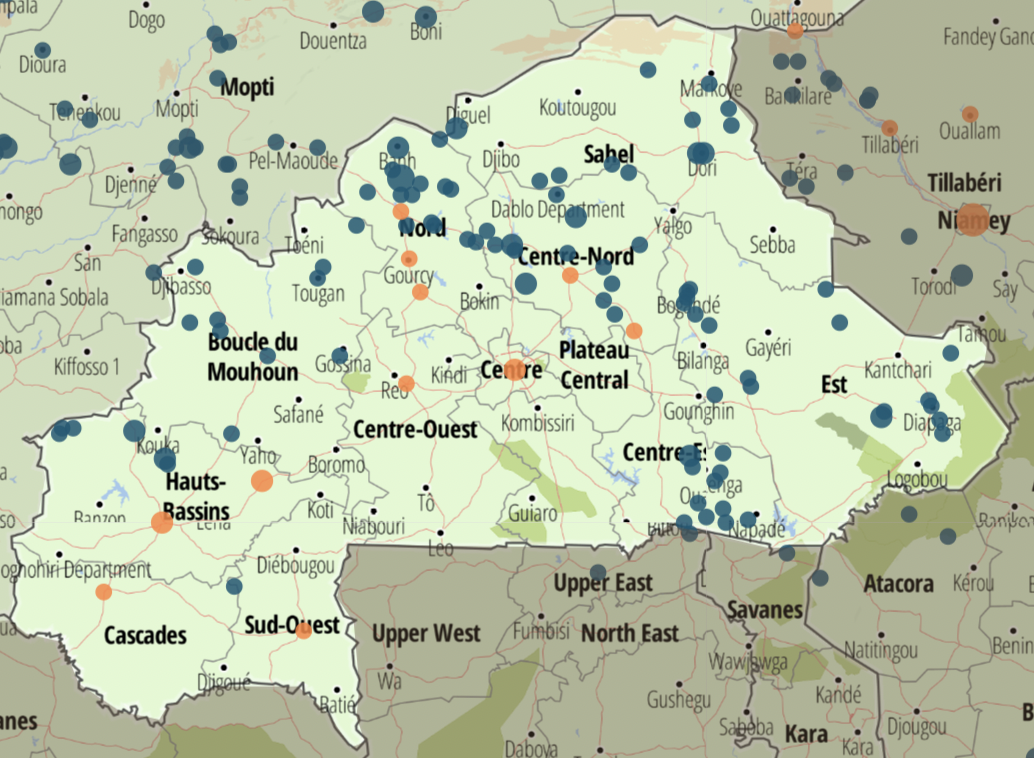

The above image depicts all identified incidents of political violence (blue) and protests (orange) that occurred in Western Niger in September. Source: ACLED

Burkina Faso

Over the last year, levels of violence in Burkina Faso have been drastically higher than in both Mali and Niger. According to Omar Alieu Touray, the president of ECOWAS, Burkina Faso experienced 2,725 attacks in the first half of 2023, as opposed to 844 in Mali and 77 in Niger. The Burkinabe government now controls less than 40% of the country’s territory; the other 60% remains ungoverned or overrun by JNIM. Dragonfly Intelligence believes that - similar to the situation in Mali - the Forces Armées du Burkina Faso (FABF) are likely to continue to lose territory to JNIM. Dragonfly also highlights the apparent disorganisation of the FABF and JNIM’s desire to take the capital, Ouagadougou.

Since Touray’s statement in July, ACLED data confirms that attacks have continued at a rapid pace across most of the country. JNIM now carries out frequent attacks in all regions, apart from four regions that encircle the capital, Ouagadougou. Attacks were previously more frequent in the north and east, but have also become frequent in the country’s southwest near the border with Ivory Coast, where there was a sharp increase in attacks in August. According to the ISS, terrorists use illicit markets in Northern Ivory Coast to fund their efforts in Burkina Faso and elsewhere.

Based on reporting from Burkinabe news source RTB news, FABF conducts daily airstrikes against JNIM. In their campaign to rid Burkina Faso of JNIM, human rights groups have accused FABF of extensive, persistent human rights abuses. Abuses are likely to continue to drive more people into extremist groups. As Ibrahim Traoré, the president of Burkina Faso, is facing an uphill battle against jihadists, he appears likely to appeal for outside help; however, given his country’s international isolation, his only option may be the Wagner group.

Recent Developments

15 September - JNIM announces via their Al-Zallaqa media channel that they attacked FABF in Bassum, Kaya state (roughly 100km northeast of Ouagadougou), killing 10, and that they carried out an attack in Benin, killing 3.

15 September - JNIM announces that they ambushed FABF in Yimberella and Korqirla, Houet province, Western Burkina Faso, killing at least 5.

24 September - JNIM announces that they assaulted FABF in Boungou, Gourma, Eastern Burkina Faso.

27 September - JNIM announces that they killed 2 soldiers in Titu.

28 September - JNIM announces that they assaulted FABF in Diaradougou, Houet province.

8 October - Burkinabe news agency RTB news announces that FABF struck terrorists that had attacked civilians in Biba and To, Nayala province, Northwestern Burkina Faso.

Operational Forecast

It is unlikely that - even in the event of Wagner assistance - FABF will be able to effectively abate JNIM attacks across the majority of Burkinabe territory over the next 6 months, and it is unlikely that FABF will take significant territory back from JNIM in the same time period.

It is likely that JNIM will carry out attacks in increasingly close proximity to Ouagadougou, within the regions of Centre-Ouest and Plateau Central, and it is likely they will attempt to carry out an attack in Ouagadougou over the next 6 months.

Although Ouagadougou is likely to remain generally stable over the next 3 months, there is a reasonable possibility that JNIM will capture Ouagadougou within the next year.

Flights to and from Ouagadougou are unlikely to be significantly impacted by conflict over the next 3 months.

As is the case in Mali, human rights abuses, a lack of economic opportunities, and a need for protection are very likely to continue to drive people to join armed groups over the next year.

Nordgold, a Russian mining company, is very likely to continue to face protracted challenges to its mining operations at its mines in Bissa, Bouly, Taparko, and Yimiougou, as well as severe supply chain related challenges.

The above image depicts all identified incidents of political violence (blue) and protests (orange) that occurred in Burkina Faso in September. Source: ACLED

The End of MINUSMA: An Uncertain Future for Mali’s Security

On 16 June, the Malian transitional government asked the UN Multidimensional Integrated Stabilization Mission in Mali (MINUSMA) to terminate all activity in the country. The UN mission, currently comprised of 15,000 personnel, had been involved in Mali as a peacekeeping force since 2013. Its aim was to help facilitate peace amidst a war in 2012 between the Malian government and armed separatist groups in Northern Mali; Tuareg separatist groups were demanding the independence of a region they call ‘Azawad.’ In accordance with the Malian government’s decision, the UN Security Council voted to conclude its operations and progressively withdraw its personnel, a process that will likely be completed before the end of this year. The transitional government’s decision was not completely unforeseen; the military junta had begun to make changes in the actors and methods employed in combating terrorism since it claimed power in 2021. The countries involved in the MINUSMA operation were concerned by this decision, taken by a government which is still largely struggling to maintain peace and abate the threat of advancing terror groups. The presence of Wagner troops is another source of anxiety for the West, as the group’s deployment represents a further extension of Russian influence on African soil and could be detrimental to peace and security in the country.

The Malian Foreign Minister, Abdoulaye Diop, justified his government’s decision by highlighting MINUSMA's failure to resolve the security crisis in Mali after 10 years of engagement. He also claimed that the mission’s reporting of human rights violations fostered distrust towards the government and fuelled communal tensions. The UN published a report in May 2023 accusing - through a well-evidenced investigation - the Malian Army and foreign mercenaries of killing 500 civilians during a counterterrorist operation in Moura a year prior. This accusation contributed to the deepening of tensions between the UN and the Malian government. In response, Mali announced the opening of an investigation against the multilateral organisation for “espionage, undermining the external security of the state” and “military conspiracy.” This decision follows a general shift in the country’s security strategy undertaken by the transitional government.

Since 2019, Russia has been actively engaged in a propaganda campaign in Mali that has effectively swayed public opinion. Russia has deployed paid and non-paid activists and influencers, multimedia platforms, and bot accounts on social media platforms to successfully win over hearts and minds in Mali. According to Jean le Roux of the Atlantic Council, Russia coerces communities “through the influence of these talking heads,” referring to local activists. Many of these disinformation efforts are being directly carried out by the Internet Research Agency, a bot farm financed by Yevgeny Prigozhin, the head of the Wagner Group (now deceased). A 2023 study revealed that over 90% of Malians now trust Russia as a partner. Although the study lacks significant feedback from rural populations, it effectively paints a picture of public opinion. A similar pattern is emerging across the Sahel, particularly in Niger and Burkina Faso, who find themselves in similar security dilemmas.

A week before Mali’s decision, Malian President Assimi Goïta and Vladimir Putin had a phone conversation, likely discussing the MINUSMA mandate. According to Jean-Hervé Jezequel and Ibrahim Maiga of the Crisis Group, Russian diplomats have also attempted to limit MINUSMA’s withdrawal budget under the threat of blocking funding for other peacekeeping missions around the world. They were likely hoping to create a disorderly withdrawal that would augment the perception that MINUSMA was a failed mission, and during which the UN would have to abandon material that the Malian army and Wagner could retrieve.

Moscow has a lot to gain from the UN mission’s retreat. Putin is benefitting from countering western influence across the continent, whilst Wagner has found in Africa a great source of natural resources, as well as a space to strategically redeploy its troops after the Russian insurrection. However, for Mali, the advantages of MINUSMA’s withdrawal are less evident than its dangers. The termination of the international mission poses great risks for the country’s security, most notably for the northern regions where most of the UN bases were located. Although MINUSMA did not have a military mandate, the presence of peacekeepers in urban centres helped to reduce the influence of terror groups. In MISUMA’s absence, these groups may now consider cities to be easier targets. In addition, MINUSMA’s departure risks increasing tensions between the signatory groups of the Alger Peace Accords and the government, and could challenge the current state of territorial unity in Mali.

The Alger Accords, signed in 2015 between separatist groups and the government, established a system of decentralisation, the creation of a common army, and specific development measures for the northern regions. Few of the agreed reforms had been implemented since its signing, but MINUSMA’s departure makes it even less likely to be upheld. The UN mission not only provided government representatives and humanitarian missions with secure access to the country’s north, but also invested in stabilisation projects which created thousands of jobs for the local population. The deterioration of security in certain areas, hindering access to many of these regions, and the loss of economic opportunities accompanied by the current government’s failure to offer economic incentives to leave armed groups, are signals that the security situation is likely to continue to worsen. The Malian government signed the Algiers Peace Agreement from a position of weakness, but has been able to develop its army during the eight years since its signing. The authorities will now likely favour a solely military solution over investing in peace and economic development.

Imperfect efforts that combine security and development initiatives continue to see success in the Ivory Coast and the Lake Chad Basin Area; combatants were provided with incentives - such as amnesty, job training, and more - to leave extremist groups. In the Ivory Coast, the government coupled these programs with efforts to invest in infrastructure and public services in affected regions. In both cases, membership in extremist groups fell following the implementation of these initiatives. The Malian Junta’s security focused approach is unlikely to be successful, as it is likely to merely drive more Malians into extremist groups to protect and provide for themselves and their families. This is especially relevant in Mali given the human rights abuses frequently committed by the army and the Wagner Group.

If the Malian government continues to respond to the terrorist threat and inter-communal conflict by sending Wagner troops alongside the Malian military, who has also accumulated a grim record of human rights abuses, levels of violence and conflict are likely to worsen. Wagner has been active in Mali since at least December 2022, playing an active role in security provision in Central and Northern Mali. In doing so, the group has killed thousands of Malians. It is not clear how many were members of armed or extremist groups. Since 2020, after the first of two military coups, deaths from armed violence have more than doubled. Almost all of these deaths can be attributed to extremist violence and the security response to it. Terror groups across the Sahel, including in Mali, are targeting civilians more frequently in 2023 than in years past.

In West Africa, where security challenges often transcend national borders, this poses a serious threat to Mali’s neighbours. Over the last several years, jihadists have streamed across the Malian border with Burkina Faso, where armed and extremist groups control almost half of the country’s territory. If the Malian Government fails to take a more holistic approach to addressing extremism, extremists within Mali may begin to pose a serious threat to the Ivory Coast, Niger (where a military junta has just overthrown a government with an effective policy track record on extremism), and even Guinea, Senegal, Algeria, and Mauritania. This is why the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) has taken such a strong stance against the most recent coup in Niger, having recently deployed a standby force for a potential intervention.

The continued proliferation of terror groups across the Sahel is not inevitable, but local, ECOWAS, and western efforts to address it are being further complicated by the actions of the military juntas in Mali, Burkina Faso, and Niger. Starting in January, Algeria will sit on the UN Security Council and may be keen to get more involved in the peace process to avoid regional insecurity. The Malian opposition has also expressed its concerns, and some segments of the population are lending support to their views. Despite this, the lack of a holistic strategy and the likely prospect of increased Wagner involvement in Mali does not bode well for the country or the continent as a whole.