Burkina Faso Geopolitical Risk Assessment

Introduction

Burkina Faso (BF) is currently ruled by a military junta under the leadership of Captain Ibrahim Traoré, who came to power through a coup in September 2022. Since the takeover, the junta has adopted an increasingly militaristic and authoritarian approach, while steering BF away from alliances with Western powers, in favour of states such as Russia, who have promised the government heavy military support. Next to strengthening the junta's position, combating powerful non-state armed groups (NSAGs) is the main political driver in BF.

NSAGs mostly include Islamist terror organisations, including home-grown extremist groups and jihadist fighters from neighbouring countries. Many NSAGs operating in the country are linked to larger organisations such as al-Qaeda and the Islamic State (ISIS). Due to their ability to move across BF’s neighbours' porous borders and their desire to attack civilians, NGOs, security forces and infrastructure, they pose a serious domestic as well as regional risk, and are likely to continue to do so over the short to medium term. The lacklustre performance of previous governments and allies in their efforts to improve the security situation in BF has precipitated two coups in as many years, the expulsion of French and other Western forces, the ejection of UN personnel, and an open invitation to the Kremlin.

Executive Summary:

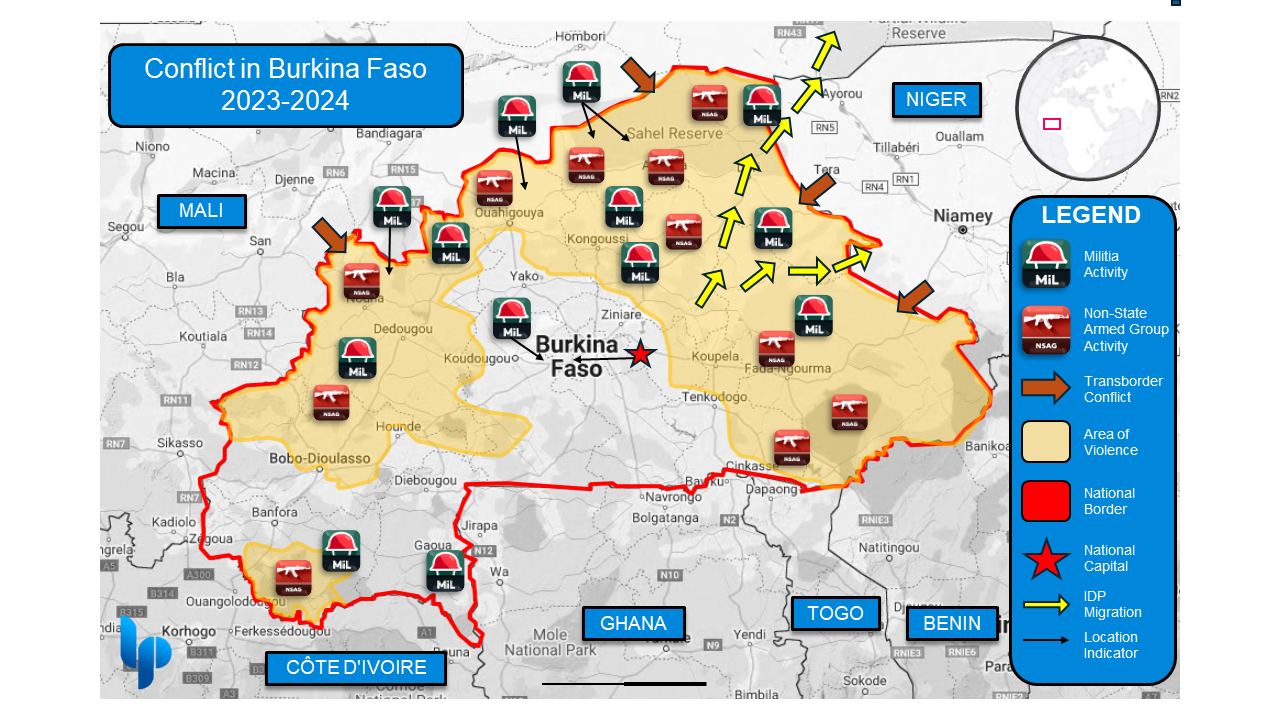

The ongoing conflict between security forces, terror groups, local militias, and external forces will very likely pose a very high risk to civilians and foreigners across the country over at least the next year, apart from central regions in immediate proximity to Ougadougu (as per Figure 1).

Harassment and violence against foreign nationals (particularly French citizens) is likely due to strong anti-Western sentiment fuelled by disinformation campaigns. NGOs and aid workers face significant risks from both NSAGs and government-linked security forces, leading to a challenging operational environment.

We assess with moderate confidence that while GDP growth will remain stable over the next 8-12 months, it will fall short of the previous years' expectations and lag behind regional partners like the Ivory Coast. Political instability, security issues, macro tail risk, and climate factors present significant challenges for individual foreign investors.

Political Risk

The number of Burkinabé civilians and soldiers killed by extremists has risen sharply over the past five years and continues to increase under Traoré’s leadership;

Despite this, public support remains high amid disinformation campaigns which label the French, UN, and ECOWAS, as corrupt entities;

Levels of corruption within government and industry are pervasive;

Russia acts as a key strategic partner to the military junta, rivalled by Turkey; and,

A formalised Confederation of Sahelian States strengthens Traoré’s government, but would very likely impact regional economics and thus global businesses and organisations, through liquidity, trade, security, and movement difficulties.

BF has experienced recurring military coups attempts over the last ten years (2014, 2015, 2022). The present government, under Captain Ibrahim Traoré, came into power in 2022 on an anti-colonial platform, as well as on the premise that the previous governments were incapable of handling the jihadist threat. On foreign policy, Traoré has taken a similar approach to BF's neighbours Mali and Niger; distancing themselves from Western states and institutions such as the UN, as well as severing ties with former colonial power France. The overall region’s influence on anti-France and pro-Russian narratives was apparent in the lead-up to BF’s 2022 coup and has created space that Russia continues to exploit via soft and hard power. In April this year, Burkinabé authorities expelled several French diplomats, after having previously ejected the ambassador and defence attaché. French nationals, businesspeople, and aid workers have also occasionally been detained, in some cases charged with espionage and subsequently deported.

Russia continues to play a strong domestic role; utilising propaganda, deploying fake social media accounts, fake news sites, and state controlled mass-media centres to conduct disinformation campaigns that have led to democratic backsliding. Russia also employs military aid to fill holes left by France and the UN in BF’s fight against jihadism. Indeed, the Kremlin has made itself an indispensable partner of the Traoré government and plays a significant role in the buttressing of broad domestic support for the junta.

Turkey also works to maintain economic, religious, educational, industrial, and military ties with BF, making President Erdoğan a key regional player with significant soft power. The two nations hold several joint commissions and agency corporations, which facilitate the transfer of Turkish development aid, student exchanges, and the sale of significant military equipment – such as the Turkish TB2, a medium altitude, long endurance, ISR and attack drone that has been linked to several human rights violations in BF.

The ‘transitional’ government under Captain Traoré has so far signalled little interest in shifting the country towards democratic rule. In September 2023, the junta cancelled elections scheduled for July 2024, and postponed them indefinitely, labelling them “not a priority”. Governing power remains bundled centrally in the putschist executive, after elected and other transitional bodies were dissolved post-coup.

We assess that public support for Traoré's government remains high, at least in the capital and surrounding regions, with no signs of major unrest/dissidence over the last six months. However, political indicators, such as message control and quickly deployed counter-factual narratives, suggest that the government's popularity can, to a significant extent, be attributed to Russian disinformation campaigns. Traoré’s stability is also maintained through a propagandist civil-political organisation known as the Wayiyans. Acting largely as a watchdog, the organisation is active in a range of activities, from political rallies to vigilante ‘stability’ patrols around the capital. Traoré has effectively dulled any major internal political opposition.

Reporting around a lone gunman attack at the presidential palace in Ouagadougou further demonstrates the depth and sophistication of information-operations within Burkina Faso. The incident in question does not have any obvious political connection, however, local news and social media quickly framed it as a failed coup attempt, spinning a narrative of demonstrated regime strength.

Anti-government demonstrations, which have declined significantly since Traoré’s coup, were frequently centred around anti-French sentiment. Since the recent departure of French troops, they have largely died down. Even though the population appears pro-government, increased reporting around human rights violations perpetrated by local militias, the expulsion of certain news outlets, and a decrease in civil liberties might increasingly fuel disenchantment among the population.

Regional observers have reported on isolated incidents of internal dissent, such as the formation of the political group FDR (The Front for the Defence of the Republic) in early April 2024. The organisation's spokesperson, Inoussa Ouédraogo, called for the “immediate release of all those forcibly conscripted, kidnapped or sequestered by the militias under the orders of Ibrahim Traoré.” However, as of today, the lack of civil unrest and protests suggests that opposition movements have not managed to gain significant momentum. This could change if the junta is not able to produce results against NSAGs over the next 12-24 months, as failure to address the jihadist threat has been a driving factor in past transitions of power.

Since Traoré’s coup, the junta has also been pursuing closer cooperation with the military governments of Niger and Mali. During a recent summit in the beginning of July, the neighbours announced the formalisation of a Confederation of Sahel States (AES). The alliance strengthens the position of Traoré and his colleagues, while further isolating them from the regional Economic Communities of Western African States (ECOWAS) block. The AES’s main goal is increased security cooperation but it also seeks to improve economic ties. For instance, the three leaders have set their sights on a common currency, in an attempt to move away from the French-backed CFA Franc used by many states in West Africa. This development would strongly disrupt trade stability between BF and its key trading partners, such as Cote d'Ivoire.

BF has historically struggled with corruption at the federal and municipal level. Anti-corruption protests are a recurring pattern - the most recent broke out just last year. Local authorities are commonly engaged in bribery, extortion, and rent-seeking. The commodities sector is particularly affected. Mining firms often cooperate with corrupt local authorities to attain commercial licensing or exploitation rights, leading to extensive compliance and reputational risks. Captain Traoré has paid lip-service to an increased fight against corruption with high profile arrests, but the efforts have not been far-reaching and do not reflect tangible changes. While corruption remains common, it has not increased dramatically since 2016.

Pervasive corruption causes various negative externalities for foreign investors and international firms. For instance, involvement of local branches in bribery schemes exposes multinationals to reputational and even legal risks, while refusal to participate may result in additional commercial challenges, such as difficulties in getting permits etc. Overall, corruption is a major obstacle to Foreign Direct Investment (FDI), and stunts domestic economic development.

Assessment:

London Politica assesses the overall political risk level in Burkina Faso as high due to Burkina Faso’s vulnerability to government collapse, or state violence, given the country’s long history of forceful transfers of power. High levels of political risk associated with political instability and regime change pose a significant risk to entities that rely on policy continuity, including foreign companies that hold public contracts with the current government.

We assess as likely that the competition between Russia and Turkey will increase over the next 6-12 months, manifesting in a range of sectors, including industry, security, defence, and information. Global tensions between NATO and Russia may play a larger role in the region as a result. Firms from either block may face additional pressures when geopolitical frictions spill over into the investment sphere. Indeed, actors on both sides seek to use government access to consolidate their economic influence. The same could be true for NGOs, who may be perceived as foreign government entities and therefore are at risk of mistrust and discrimination by local authorities.

Further, we assess that over the next 6-12 months foreign nationals, particularly French citizens, are at a high risk of harassment or violence by local populations or extortion by government representatives. This endangers business continuity in the country and negatively affects the investment outlook for lenders as well as capital allocators, leading to a more complex and challenging commercial environment for foreign actors.

Security Risk

Terrorism is at an all-time high in Burkina Faso, with over 2,000 fatalities and 1,312 civilian casualties in 2023;

Civilian casualties often occur in any area where NSAG (Non-State Actor Groups), government forces, or the Volunteers For the Defence of the Homeland militia (VDP) are operating;

Ongoing information operations have a significant effect on the disposition of government forces, especially the VDP militias who are a poorly trained and unprofessional force;

NGOs and foreign nationals have experienced discrimination and violence by both NSAGs and government security forces.

BF’s security situation has deteriorated since 2023, as security forces, including local militias, are ramping up their presence and operations in NSAG controlled territory. The Figure below provides an overview of the conflict, highlighting areas of reported militia and NSAG activity that has resulted in casualties or collateral damage. London Politica’s research supports an assessment by ECOWAS, which highlights that Burkina Faso’s government controls less than 60% of the country.

NSAGs and Terrorism

BF currently experiences the highest frequency of terror attacks globally. In 2023 alone, around 2,000 people were killed in terror related incidents. In fact, over a quarter of the world’s terror related deaths occurred in the country in that same period. Notable incidents in 2023 included the killing of 71 soldiers in the province of l’Oudalan by an IS Sahel faction and the murder of 61 civilians in Partiaga, a village in the Tapoa province, by Jama’at Nusrat al-Islam wal-Muslimin (JNIM). [see London Politica Sahelian Security Assessment for JNIM profile] JNIM remains the dominant terror organisation in the country. More recent examples include an attack in February 2024, in which terrorists targeted a Catholic church in the north-east, killing 15 worshippers. On the same day, militants massacred several dozen civilians in a mosque in the south-eastern city of Natiaboani. These incidences were reported over X by local journalists.

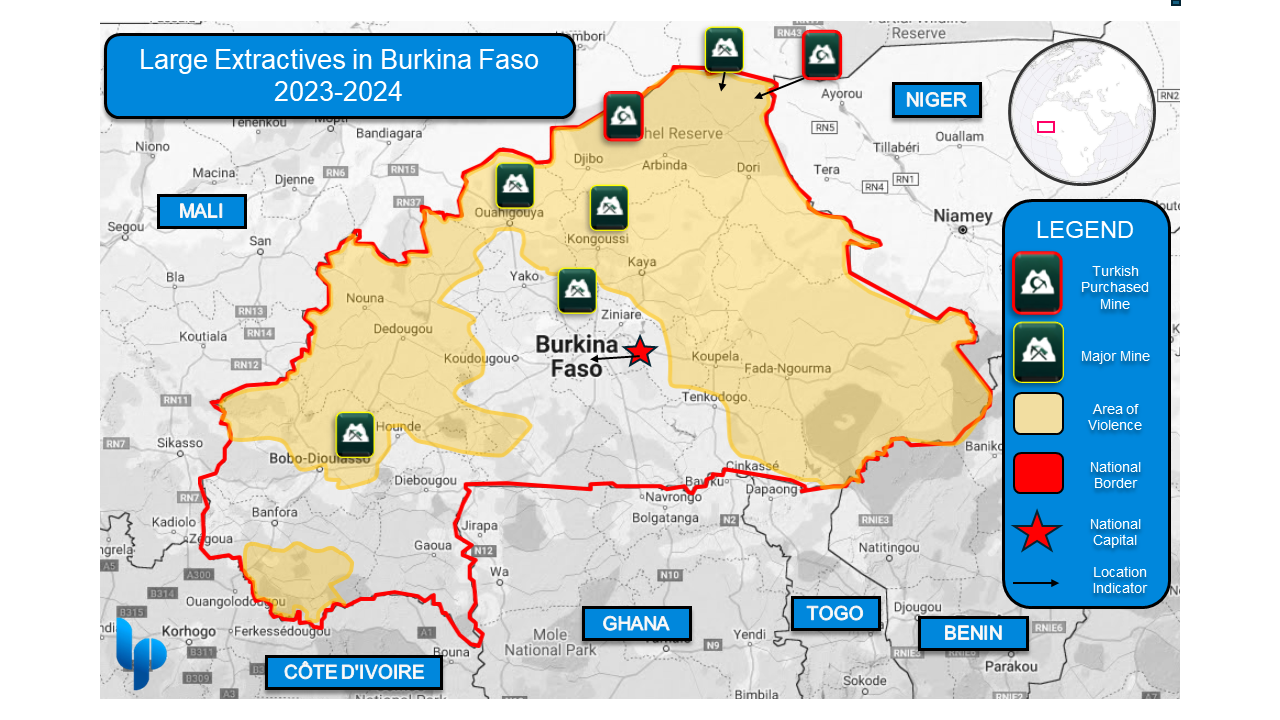

Insurgent guerrilla strategy - including ambushes and hit-and-run tactics - are prevalent in BF. JNIM, for instance, conducts both sophisticated and simple IED attacks to create disruption and tunnel targets into favourable attack positions. Both JNIM and other NSAGs engage in kidnappings to extract ransom payments and organised intimidation tactics to levy taxes on local businesses and NGOs in their territories. Human and arms trafficking is also pervasive in militant controlled regions. NSAGs are also leveraging access to the illegal gold trade and sale of looted government or NGO supplies, to finance their operations. JNIM, for instance, has been aggressively trying to expand their grip on lucrative mining regions, where they mine and smuggle gold, but also provide paid security for locals engaged in artisanal mining.

Terror attacks continue to occur across the country, with a particularly high frequency near the Malian border and the tri-border region between Burkina Faso, Niger and Mali, where militants take advantage of weak border security. The centre of the country, particularly in close proximity to the capital, has been comparatively safe.

Government Security Forces & Vigilante Militias

International observers have also accused government security forces of violence against civilians. Human Rights Watch (HRW) recently published a report accusing the army of killing 223 villagers in February, near the northern border to Mali. HRW has highlighted numerous civilian casualties resulting from TB2 drone strikes, in both 2023 and 2024. Militias have also been accused of atrocities. Reports indicate that the Volunteers for the Defense of the Fatherland (VDP), a national militia created by the Burkinabe government, massacred 156 people in the northern village Karma in April 2024. Their attacks, which have also included forced disappearances and summary executions, often target ethnic Fulanis, who are perceived as extremists by factions of the militia.

The VDP has a strong presence on the front-line against NSAGs, often suffering heavy casualties. The militia relies on quick recruitment and poor training to ensure rapid deployment. While VDP personnel have benefitted from a recent 30% pay rise, the group has also been implicated in criminality, including extortion and kidnappings. As the VDP recruitment numbers have grown, so has NSAG retaliation against communities linked to the militia. IDP camps, perceived as VDP loyal, have suffered reprisal from groups, including from al Qaida-affiliated organisations.

Sporadic social media reporting also suggests a decrease in the recapture of territory, with an increase in permanent army checkpoints on key roads, enacted curfews and declared states of emergency in the most affected northern provinces.

NGO staff, in particular those operating in contested regions, also face increasing harassment and violence from both NSAGs and security forces, including the VDP. Amnesty International reports high-levels of mistrust against NGO members amongst locals and the military alike, who sometimes suspect aid workers of supporting jihadist organisations. These attitudes are boosted by the spread of disinformation. Attacks on NGO staff have ranged from discrimination and wrongful detention to beatings and murder. NSAGs also frequently loot aid convoys. We assess that these risks will not abate over the next 12-months and NGOs operating in conflict zones, particularly around internally displaced persons in the north and northeastern provinces, will have to continuously monitor their security exposure to both government troops and NSAGs.

External Forces

Reporting on the specific activities of the Kremlin-backed Africa Korps remains sparse. The unit, which was established after the disbandment of the Wagner Group, employs mercenaries (including former Wagner members) as well as volunteers, and operates under the umbrella of the Russian defence ministry. While the Russian paramilitaries were originally brought in under the guise of filling the French anti-terror gap, regional sources indicate that their main mandate is to protect the military government, enabling the junta’s political aspirations while carrying out targeted missions and training Burkinabé forces. The organisation continues to recruit heavily across the Russian-speaking world, but has also signalled the desire to expand their ranks locally, in BF. The group has been linked to civilian deaths in neighbouring countries, but continues to enjoy a strong backing by BF’s central government.

Assessement:

London Politica assesses that continued, widespread violence between NSAGs and security forces are highly likely over the next 12 months. It is unlikely that the security situation in the non-capital regions will improve, as government forces have not been able to effectively combat NSAGs in contested regions causing violent spillovers affecting civilians.

We assess that the targeting and harassment of NGOs and foreign nationals by security forces will remain highly likely over the next 12 months. Travellers are advised to avoid known areas of conflict, including the northern border regions of Soum, Oudalan, and Seno. Additionally, travellers should limit travel to main service routes around the capital-south regions around Ganzourgou, Boulgou, Naouri and Bazega. Professionals and aid workers are also advised to hire armed escorts ahead of travel and have emergency backup routes prepared. Staff deployed to conflict regions are exposed to the risk of violent attacks, looting of supplies, and kidnappings by terror organisations. They are also at risk of harassment, detention, torture, and murder from government troops, particularly in regions in which the VDP operates - such as Seno, Kossi, Tapoa, Bam, and Yatenga.

Economic Risk

Burkina Faso's economy is projected to grow by 5.5% in 2024, driven by gold, manganese, cotton, and agricultural production. However, political instability and security issues, particularly attacks on industrial centres, pose significant risks to economic development.

Inflation has slowed due to stable commodity prices and monetary policy, but the macro environment remains volatile.

Turkey's FDI ambitions faced setbacks with revoked mining licences, while disputes among foreign investors highlight the challenging business environment.

Burkina Faso’s economy is driven by the production of gold, manganese, cotton and agricultural goods. The IMF has projected that the country’s economy will grow by 5.5%, slightly lower than the average of 6% from 2017-2019. The lagging economic performance is largely attributed to the precarious security situation and political instability.

Inflation, previously a grave concern to policy makers, has slowed down, mainly due to stabilising commodity prices and a monetary tightening of the Central Bank of West African States. The macro environment remains challenging, however, and resurging inflationary headwinds cannot be discounted over the next 12-months.

Overall, the country’s economic outlook hinges largely on the political and security situation. Indeed, many of the major industrial centres are located within contested regions and are prone to attacks by NSAGs. Extractives businesses are at particularly high risk. Additional headwinds will likely include climate events, such as reduced rainfall or drought, damaging agricultural yields. Presently, growth appears largely stable, positioning BF’s economy on solid footing, compared to regional standards.

A notable development in terms of FDI is the increasing influence of Turkey. Besides the sale of military equipment, Turkish firms are expanding into other business areas. The mining venture Afro Türk, for instance, purchased licences for the Tambao manganese mine and the Inata gold mine for $50 million in April 2023. However, in late March 2024 the operating licences were revoked again, due to failure to deliver full payment. The licences have since been handed over to new undisclosed investors. This set-back was a blow to Turkey’s ambitions and their relationship with the government. The now-defunct contract between the junta and the Turkish miner contained a noteworthy clause, which required the company to build security infrastructure for military forces fighting the NSAG threat in the vicinity of the mines, which is demonstrative of the pervasive threat these groups pose in the north of the country. This is also an indication of a broader, unspoken, trend; investors need to demonstrate alignment with the central government in order to win business, at least in major state-backed industries. Hence, this adds to the considerations of foreign business ventures, who might be wary of cozying up to an authoritarian government.

A recent dispute between Lilium Mining, the largest gold-producer in West Africa, and Endeavour Mining, a Canadian conglomerate, further demonstrates the challenging business environment in BF’s conflict zones. During the summer of 2023, Endeavour finalised a deal to sell their Boungou and Wahgnion mines to Lilium, due to the constant threat of attacks by terror organisations. The $300 million deal has since turned sour, as Endeavour brought forth a lawsuit, accusing its counterparty of failing to pay the agreed sum in full. Lilium in turn has launched legal proceedings against Endeavour, claiming they were misled regarding the operational capacities of the mines. Hence, the precarious security landscape poses serious challenges for foreign investors, especially regarding business continuity, but also when it comes to appraising investment opportunities, including the pricing of counterparty-risk.

Assessment:

BF’s economic landscape presents a high-risk environment for foreign firms considering launching or expanding business operations. The interplay of political instability, the presence of armed groups, geopolitical tensions, and other macro drivers creates significant challenges for investors. A high risk appetite is required.

We assess that the country’s economy is heavily reliant on commodity prices (cotton, gold). This dependency makes the macroeconomic environment highly volatile. Foreign firms must be prepared (hedges etc.) for significant fluctuations in revenue linked to global commodity markets.

It is highly likely that climate change exacerbates the frequency and severity of adverse weather events, presenting ongoing risks to economic stability and individual business operations. While extreme tail risk events such as the insect infestations that decimated cotton production in 2022 are unlikely, they remain a present risk that can have significant localised and macroeconomic impacts.

Political instability remains highly likely over the next year and a change in sentiment or government may bring about nationalisation of foreign-owned assets. International firms must navigate the political landscape cautiously, nurture good relationships with local and federal government, and develop contingency plans to mitigate the risk of abrupt policy changes.

The country hosts a high number of IDPs, resulting in a weakened workforce, leading to difficulties for foreign businesses seeking reliable labour. Companies must consider strategies to address potential labour shortages and invest in workforce development.

Infrastructure Risk

Infrastructure remains unreliable both due to underdevelopment and damage as a result of ongoing conflict;

Access to water and medical supplies are limited outside the capital, and competition over basic resources may lead to conflict

NGOs and commercial enterprises are likely to face difficulties traversing outside of the national capital region as a result of poor telecommunications and road infrastructure.

The conflict has heavily damaged infrastructure across BF. Attacks on water points are common, and according to UNICEF, results in increased water scarcity, with some regions losing regular water access for up to 223,000 persons.

With BF’s paved and maintained road systems reaching just over 1,000 km in 2021, transportation can be a challenge, particularly in the hinterlands. Road systems’ traversability is likely to be worsening in the north to north-west regions as a result of intense heat and ongoing conflict. Major bridging and paved roads have also become targets for IED attacks and convoy ambushes, in systematic attempts to limit vehicle movement and the flow of supplies to besieged areas.

Access to medical supplies and treatment has also been heavily affected by the ongoing conflict. In embattled regions medical facilities are frequently forced to cease operations, due to a lack of resources and looting by NSAGs. Indeed, in provinces such as Soum, as much as 65% of health infrastructure is non-functional. NGOs seeking to deliver medical care will be particularly challenged by the lack of pre-existing facilities and the threat of looting. In affected areas, NGOs would be well advised to hire a security detail to protect their staff and property.

The country’s telecom sector has made significant inroads over the past four years, reaching a fibre-capable backbone that links over 145 central communities and implementing terrestrial cables to neighbouring countries. Despite this, much of the country's cellular capabilities remain largely underdeveloped, as much of the country still relies on regional 3G.

In their late 2023 Burkina Faso country brief, Janes reported that while attacks on critical infrastructure are recorded and common, the largest threat to infrastructure remains weather-linked risks, such as heavy rainfall and floods. The World Bank has additionally highlighted that drought-like conditions are another major risk variable regarding food and water insecurity.

Assessment:

We assess that major infrastructure and industrial sites within the; Boucle du Mouhoun, Nord, Centre-Nord, and Sahel regions are under moderate short-term risk - due to historic assaults by NSAGs who have demonstrated a willingness and capability to carry out targeted attacks. These circumstances are highly unlikely to change in the next 12-24 months, as the threat to infrastructure is particularly high in conflict zones, towards the northern borders with Mali and Niger due to an increase in NSAG blacktracked trafficking and smuggling routes which have proven effective against Government Forces. As a result, NGOs and businesses operating in these regions must be prepared for delays in supplies delivery - due to ambushes and IED attacks - and should therefore keep a well-secured inventory of basic items and materials needed for operational continuity. Travelling across the Nord to Sahel regions should also be limited to self-established safe-routes, alternating in frequency and changing routes frequently.

The junta has increasingly focused on protecting infrastructure. The adoption of technology solutions, such as drone surveillance, as well as the presence of the Africa Corps has reduced the number of attacks over the last 12 months. The reduction in violent incidents, however, is not a perfect indicator of the government’s success against terror groups, as defending fixed infrastructure is easier than uprooting highly mobile terror groups.

Individuals and organisations should also prepare for civilian telecommunications coverage dead zones and blackouts, as well as bring health and water supplies. Doing so will ensure preparedness for lack of availability, but it is better to do so moderately as to not draw unwanted attention.

Societal and Legal Risks

Inter-community violence in Burkina Faso has increased, especially against the Fulani minority and the country hosts around two million IDPs and 40,000 refugees.

Russian disinformation campaigns influence public sentiment, and the government restricts media freedom, suspending various international news outlets and digital platforms.

Homosexuality is illegal in Burkina Faso as of 10 July 2024 and discrimination is pervasive.

BF is a multi-ethnic state, in which the Mossi people make up the majority of the population (54%). Reports of inter-community violence have intensified over the last five years, with claims ranging from harassment to skirmishes between ethnic militias. Due to their perceived ties to terror organisations, the Fulani group (7%) has been among the most persecuted minorities in BF. They face regular abuse and violence from factions of the Burkinabé security forces. The Collective Against Impunity and Stigmatization of Communities, a local civil society organisation, has reported 250 extrajudicial killings of Fulani community members in the last three months of 2023 alone. We assess, however, that despite these incidents, ethnic violence will not significantly impact levels of political stability.

BF is also home to approximately two million IDPs and hosts refugees from war-torn neighbours such as Mali. The number of refugees remains comparatively small (approx. 40,000) and their arrival has not led to observable patterns of (ethnic/community/economic) violence or unrest in affected border regions.

Homosexuality is now criminalised in BF, as of 10 July 2024. Even prior to that development, there had been no explicit protections against discrimination based on sexual orientation. Social surveys show that only 8% of the population is tolerant of same-sex relations, well below regional standards. Foreigners that are perceived as members of the LGBTQ+ community may be subject to raids, screenings, harassment, and even violence.

International observers and think tanks have continually reported on the presence of Russian disinformation campaigns within Burkina Faso. Further, evidence of groups both internal and external to the Burkinabe Government are believed to be operating pro-junta and anti-French information campaigns; with up to 11 simultaneous campaign streams sighted in just 2024. Reports have also linked the public’s positive perception of Africa Korps mercenaries to Russian misinformation campaigns. Specifically, fake social media accounts and news sites spreading anti-democracy and pro-Kremlin propaganda across channels such as YouTube. Journalists and bloggers have also been accused of being on Russia’s payroll to push authoritarian objectives.

According to Freedom House, BF has demonstrated the largest decrease in civil and political freedoms of any country in the region over the last 8 years, down 26 points since 2022. In the regional ranking, BF is etching closer to the bottom of the list. The country currently occupies the second to last spot, ahead of its neighbour Mali.

While media freedom is technically a constitutional right in BF, the junta government has frequently ordered the suspension of broadcasting and access to media outlets promoting dissent. In 2023, Burkinabé authorities suspended French news outlets LCI and France24, while removing publication and access rights to Radio France Internationale and the magazine Jeune Afrique. In April 2024, in the wake of reported human right violations and the massacre of 223 civilians by the VDP, the Burkinabé government announced the suspension of BBC broadcasting rights, and Voice of America (VOA) radio networks from broadcasting for two weeks. Websites and digital platforms including Facebook are also routinely cut off without notice.

Assessment:

London Politica assesses that the situation around civil liberties is is likely to continue to worsen over the short to medium term. As Traoré’s junta moves past the cancelled July 2024 election period, and seeks extended power, we are highly confident that the state will further utilise the means at its disposal to control the dissemination of information. Moves to retain order through the control of information may lead to information blackouts and possible targeting of region specific 4/5G L-band communication networks to halt communications all together.

Specifically in the wake of failed military operations and increased violence, a worsening of the information environment would pose a severe risk to any commercial or civil operations on the ground, severely limiting both freedom of movement and critically disrupting any operations that require telecommunication based coordination. Further, disinformation poses a direct threat to any operations which rely on local-civil cooperation due to the volatility in narrative flow. Companies and NGOs with static locations are advised to invest in telecommunications equipment not-dependent on local infrastructure or geo-regional web data.

Sahelian Security Tracker - Chad

Executive Summary

TLDR: Chad is likely to remain generally politically stable over the next 6 months; large-scale protests are unlikely and rebel groups are unlikely to effectively challenge the government.

Intercommunal tensions in the east exacerbated by refugee flows from Sudan are unlikely to result in large-scale conflict in the short term, although isolated incidents of ethnic/intercommunal violence remain possible.

Although there may be a small terrorist presence in Southwestern Chad, it is unlikely that terror groups will gain any territory in the country in the short to medium term. Attacks on N’Djamena or major population centres remain unlikely, while there is a reasonable possibility that terrorists may conduct attacks in the Lac region in the short term.

The threat posed by criminal groups in the south/southwest is also unlikely to be abated over the short to medium term.

*The yellow icons indicate locations that are more likely to see protests in the event of domestic unrest, and we did not include communal violence as it is an omnipresent risk in nearly every region of Chad.

Introduction

Chad currently faces many security challenges, exacerbated by the war in Sudan and the proliferation of terrorism across the Sahel. Although conflict in Sudan’s Darfur region has not yet extended into Eastern Chad, continued migrant flows risk increasing communal tensions between farmers and herders over natural resources, a risk that is worsened by weapons smuggling and the presence of armed groups that have previously engaged in ethnic conflict. In Chad’s southwest, military campaigns and tensions between jihadist groups over the last year have largely mitigated the threat of direct terrorist action in Chad, but the threat posed by terror groups persists. In the south/southwest, criminal groups continue to carry out kidnappings for ransom with near impunity.

Further, the first half of 2023 saw a 150% increase in inter and intra-communal violence in Chad compared to the first half of 2022, the vast majority of which was concentrated in the south, near the border with the Central African Republic. This occurs amidst a backdrop of political instability - protests over the last several years have left hundreds dead and rebel groups in the far north have officially renewed their campaigns against the government. Even so, in December Chad’s transitional government, led by Mahamat Déby, reached an agreement with the largest opposition party, likely quelling the immediate threat of large-scale instability. Elections are scheduled for November 2024.

Refugee Crisis in the East

Security-related developments in Eastern Chad are largely dependent on events in neighbouring Sudan. So far, the war in Sudan has driven at least 500,000 civilians into the eastern Chadian provinces of Ouaddaï, Sila, Wadi Fira, and Ennedi-Est. According to the UN, this is adding to pre-existing socioeconomic pressures in the region. Temporary camps remain erected on lands previously used for farming and herding, which has exacerbated the shortage of basic resources that has previously driven violence between ethnic groups.

Largely because of the conflict in Sudan, in which Arab armed groups - principally the Rapid Support Forces (RSF) - with ties to the Darfur genocide have committed ethnic violence against Black African communities, mistrust remains prevalent between Black African and Arab ethnic groups in Eastern Chad. Although some analysts hold that the RSF may follow Black Africans into Chad and commit atrocities, we assess that this is very unlikely to be carried out systematically in the short term as the focus of the group’s leadership remains on taking control of Sudan and garnering global legitimacy.

According to the International Crisis Group, Arab refugees in Eastern Chad feel unfairly associated with the actions of the RSF as NGOs have given first priority to Black African refugees, and as Arabs are suspected of sending their sons to fight with the RSF. In this context, it remains unlikely but possible that NGOs may face direct attacks by disconcerted Arabs or armed groups. In our review of local media sources and social media, we have not identified any episodes of ethnic or communal violence in Eastern Chad since the start of the war in Sudan. We have however identified incidents of purported abuses at the hands of the Chadian security forces as they crack down on weapons smuggling to abate communal conflict.

The presence of weapons indicates that groups or individuals would have the capability to commit mass violence but so far lack the intent to do so. This may change as the war in Sudan continues, more refugees pour into Chad, and resource scarcity becomes more acute. Regardless, we maintain that large-scale violence remains unlikely in the short term as the Chadian government is heavily incentivised to remain uninvolved in the conflict in Sudan; Déby’s transitional government is dependent on support from Black African and Arab elements, neither of which support the RSF (a group that several news outfits suggest Déby is allowing the UAE to aid via Chad). Additionally, large Chadian troop deployments in the east are likely to mitigate the risk of large-scale communal violence. Given past precedent, incidences of ethnic violence are most likely to occur in Ouaddaï.

General Political Stability

Over the last few years, there have been a number of large-scale protests and violent responses from security forces, particularly in N’Djamena. These protests were driven by a perceived power grab by current President Mahamat Déby after the death of his father, President Idriss Déby, in clashes with Front pour l’alternance et la concorde au Tchad (FACT) in the north. Although some opposition parties boycotted the recent agreement between the ruling Mouvement Patriotique du Salut and the opposition Les Transformateurs, the agreement has largely mitigated the threat of instability in the short term by bringing a number of stakeholders into the fold. The government has also pardoned the vast majority of protesters who had previously been arrested.

Despite this, according to an expert we spoke to for this assessment, much of the Chadian public remains disillusioned with the government, few of which turned up to vote in the constitutional referendum in December. This expert believes the official voter turnout number was falsely inflated and that unrest after or in the run-up to the November elections is likely. We maintain that, in the event of unrest, future demonstrations are most likely to occur in large population centres in the south/southwest of the country, and would likely pose incidental risk to foreign companies and NGOs, and may pose a direct risk to those that have easily identifiable ties to the west. Previously, the largest protests took place in Chad’s two most populous cities, N'Djamena and Moundou. Other southern cities such as Doba, Bébédjia, and Koumra have also seen a number of demonstrations.

In the past week, Mahamat Déby travelled to Moscow to meet with Vladimir Putin, signalling closer security cooperation between the two governments. Putin praised Déby for holding the December referendum and pledged the Kremlin’s support for further stabilising the country. The private aircraft on which Déby travelled to Moscow belongs to the same Emirati company that has shuttled RSF leader Hemedti to meetings with neighbouring leaders. We hold that closer security cooperation between the Kremlin and N'Djamena and the departure of French troops make large-scale demonstrations less likely in the short to medium term.

Chad remains in recurring conflict with rebels in the gold-rich northern Tibesti province; various factions based in southern-Libya continue to engage in skirmishes with Chadian security forces. In June 2023, the army halted an incursion of the Front national pour la démocratie et la justice au Tchad and Conseil de commandement militaire pour le salut de la République rebel groups in the Kouri Bougoudi region, home to Chad’s largest goldfield. Some rebel groups are also active in Sudan, fighting alongside the RSF. This may allow the rebels to gain a stronger footing in Sudan, making it more difficult to uproot them, especially given Mahamat Déby’s public neutrality in the conflict. Even though it is unlikely that the Chadian government will succeed in fully defeating various rebel groups, they will unlikely pose a serious threat to the stability of the country in the short to medium term. However, as the November elections approach, rebel groups may see more popular support within the country, emboldening them further.

Insecurity in the South / Southwest

The largest source of insecurity in Southern Chad is the proliferation of violent crime, in particular kidnappings for ransom. Local media sources report that criminals are responsible for a string of kidnappings, especially in the Mayo-Kebbi Est and Mayo-Kebbi Ouest border regions with Cameroon. Kidnappings are also increasing in N’Djamena. Victims include farmers and students, and recent evidence suggests that criminals are operating across borders. Criminal or armed groups have not yet targeted NGO workers and foreign business people, but high rates of persistent criminality and impunity suggest they face increased levels of incidental risk. They may be directly targeted in the near future given the perceived resources at their disposal. Even though the government is ramping up its response to criminal groups, we foresee a continued heightened kidnapping risk over the short to medium term. There is also a risk that criminal organisations have or will collaborate with terror groups in Chad, as they have in Nigeria, which would likely increase their capabilities.

The Lake Chad region, covering parts of Cameroon, Niger, Nigeria, and Chad is a hotbed of terrorist activity, and is a stronghold for Boko Haram and the Islamic State – West Africa (ISWAP); however, conflict between the two and factional infighting has weakened them. The continued security response by the Chadian army - buttressed by material support from the UAE - and the Multinational Joint Task Force (MNJTF), have diminished the jihadists' capability to carry out attacks.

There have been reports of terror attacks in very close proximity to the Cameroon/Chad border. The jihadists’ ability to move in small groups to attack villages and civilian targets, especially in the border region, is unlikely to be subdued by the government’s security response in the short to medium term. Past precedent around attacks in Chad indicate that terror groups are more likely to target Chadian soldiers than civilians, and present the largest threat in the Lac region, where a large number of humanitarian organisations operate. These groups present an existing threat in the rest of the border regions with Cameroon and Nigeria, including in N’Djamena.

The south of the country has also recently seen a sharp uptick in communal tensions resulting in violence. In May, a herder-farmer dispute in the Mandoul province led to the deaths of 9 people, including a child. Earlier that month armed “bandits” slaughtered 11 farmers in a neighbouring region. The UN OCHA reported 30 incidents of communal violence in the south during the first half of 2023 alone. Conflict over scarce resources is likely to drive further inter-communal violence. NGOs and IGOs have so far been unaffected by the local tensions and outbreaks of violence, but there is a large presence of humanitarian organisations in the south that may face incidental risk and may be targeted if they are perceived as providing assistance along communal lines.