Serbia’s Jadar mine: the energy transition and environmental concerns

Introduction

Following government plans to reboot the Jadar lithium mine proposed by mining giant Rio Tinto, thousands of protesters rallied in Belgrade over the past month. The mine is set to become the largest lithium mine in Europe, significantly boosting Serbia’s economy, and supplying 90% of Europe’s lithium needs. However, the project has also sparked nationwide protests with concerns over the potential impact of the mine on the local environment. With increasing global demand for critical minerals, the Jadar lithium mine highlights broader tensions around resource extraction and the energy transition. This article analyses the implications of the mine and explores the different stakeholder perspectives that pose risks to its commencement.

Background

With the European Union's (EU) increasing demand for lithium, driven by the transition to electric vehicles (EVs) and energy storage, developing a secure lithium supply chain is growing in importance. Portugal is the only EU state that mines and processes lithium, making the region and its green transition heavily dependent on external sources. In response to this vulnerability, the EU has introduced the Critical Raw Materials Act (CRMA), which aims to reduce reliance on imports by promoting domestic production and refining capabilities. The proposed Jadar lithium mine in Serbia, with estimated reserves amounting to 158 million tons, could play a pivotal role in this strategy, with plans to produce 58,000 tons of lithium annually – enough to support 17% of the continent's EV production, approximately 1.1 million cars.

If all goes to plan, mining operations could begin in 2028. According to Serbia’s mining and energy minister, the government “aims to incorporate refining processes and downstream production, such as manufacturing lithium carbonate, cathodes, and lithium-ion batteries, potentially extending to electric vehicle production”. Moreover, in June 2021, amid public opposition in the Loznica region, the government emphasised that the project would involve a full-cycle approach to maximise local economic benefits. In March, Prime Minister Ana Brnabić suggested that the country could restrict or prohibit the export of raw lithium to support domestic value chain development. However, so far the specifics of the refining processes remain unclear.

Stakeholder perspectives

EU view

Since Europe currently has virtually no domestic lithium production, the EU views the Jadar lithium mine as a crucial project to bolster its economic security and support its green energy transition. The mine is expected to produce enough lithium to meet 13% of the continent’s projected demand by 2030, reducing its reliance on imports. Germany has already expressed strong support for the project, with Chancellor Scholz emphasising the mine’s importance for Europe's economic resilience.

Serbian view

The Serbian government views the project as a significant opportunity for the country's economy and its industrial development. Its mining and energy minister has emphasized that the project would comply with EU environmental standards while delivering economic benefits, including the creation of around 20,000 jobs across the entire value chain. Furthermore, Serbia’s finance minister projects that the mine could add between €10 billion and €12 billion to Serbia's annual GDP, which was €64 billion in 2022. To maximize these benefits, Serbia plans to follow the example of countries like Zimbabwe and Namibia by imposing restrictions on lithium exports, aiming to establish a complete domestic value chain for EVs. Additionally, Serbia's bid for EU membership adds a strategic dimension to the project, potentially aligning the country more closely with the bloc's energy and economic goals.

Local population view

Massive protests against the Jadar project have erupted across Serbia since June, following a court decision that cleared the way for the government to approve the mine. Many Serbians are troubled by the lack of transparency that evolved in the granting of mining rights to a foreign company. Moreover, opponents are sceptical of Rio Tinto's involvement, citing the company’s controversial history in developing countries, such as its operations in Papua New Guinea, where environmental damage contributed to a nine-year civil war. In this light, locals fear that the mine could jeopardise vital food and water sources in the Jadar Valley. For example, environmental problems caused by tailings, mine wastewater, noise, air pollution, and light pollution could endanger the lives of numerous communities and harm their agricultural land, livestock, and assets. Concerns have also been heightened by reports that exploratory wells drilled by Rio Tinto brought water to the surface that killed surrounding crops and polluted the river.

Rio Tinto view

Rio Tinto asserts that the Jadar mine is “the most studied lithium project in Europe,” having invested over $600 million in research and development to ensure its safety. As part of its efforts to gain public support, the company has conducted 150 information sessions for the local community, while Serbia's mining ministry has established a call centre to address concerns about the project. To further reassure the public, Rio Tinto has also expressed a willingness to allow independent experts to conduct an environmental review, aiming to alleviate doubts about the mine's potential impact on the ecosystem.

Conclusion

Despite the public opposition, the Jadar lithium mine appears likely to proceed, backed by strong support from the Serbian government and the EU, both eager to meet the onshoring requirements outlined in the CRMA. However, as this article has highlighted, the project faces considerable risks, including environmental challenges and persistent social and political opposition. The recent closure of the Cobre copper mine in Panama, following widespread protests over environmental damage and disputes over a new tax deal, serves as a stark reminder of the potential pitfalls. The Jadar project will need to navigate these complexities carefully to avoid similar outcomes and ensure a balanced approach to economic development and environmental preservation.

Examining the rise of Resource Nationalism

Recently, China’s Zhejiang Huayou Cobalt company approved plans for a new $300m lithium processing plant in Zimbabwe. The company is aggressively expanding operations in line with CCP foreign policy, consolidating rare earth resources and the infrastructure needed to process them. The investment comes after the China-based firm purchased the Arcadia hard rock deposit from Australian Prospect Resources for $422m last year. It now brings total investment by Chinese firms in Zimbabwe to over $1 billion since 2021. However, it also raises the potential benefits that resource nationalism may bring to nations, particularly those in Africa.

That is because the investment comes on the heels of recent Zimbabwean export bans on lower grades of lithium and raw lithium ores in an effort to nationalise its lithium production. In December of 2022, Zimbabwean mining minister Winston Chitando stated that ‘no lithium-bearing ores or un-fabricated lithium shall be exported from Zimbabwe to another country except under the written permission of the minister’. This move was further galvanised by the incorporation of a larger group of ‘Approved Processing Plants’ by the government, which means that any firms looking to invest in lithium operations will have to invest in Zimbabwean infrastructure in order to do business. Furthermore,in addition to relying on government approved facilities, the mining firms will have to follow the prices set by the MMCZ when selling their raw ore to processing plants.

This twofold measure not only confines the entire lithium extraction and refinement process to Zimbabwe, but also pressures foreign firms to have more vested stakes in the development of Zimbabwe. These measures have had no negative impact in Zimbabwe, as foreign investments have shown no signs of slowing. Zimbabwe is quickly reaching its target of $12 billion in production, with future plans to surpass that target in the coming years. This move by Zimbabwe, which is the 6th largest lithium miner globally,further cements the growing wave of resource bans that have become a popular way of raising revenue and encouraging passive investment in infrastructure at little cost.

Zimbabwe is an example in a growing group of nations who are racing to nationalise and control their natural resources. In the Americas, Mexico and Chile recently nationalised their lithium resources and now have total control over the extraction and refinement of the metal, which has allowed them to enjoy considerable economic benefits, in addition to increased infrastructure and employment. Whilst African and South American countries are consolidating their mineral deposits, Asian countries have also joined the fray. In 2020, Indonesia instituted a nickel ore export ban after a six-year debate. Since doing so, it has increased its smelting facilities from 2 to 13 and increased the value of Indonesia’s nickel exports from $57m in 2020, to $750m in just three years.These

By looking at these cases, there seems to be an ironclad case for resource nationalism, which has seen a resurgence owing to the rise of China as a key economic player. Both Chile and Mexico are relying on Chinese investment and demand, whilst Indonesia’s key infrastructure was developed as a part of the ‘Belt and Road’ initiative.

The role of Covid-19, however, cannot be ignored either, as the pandemic persuaded many countries to nationalise their resources. Additionally, in the case of Chile and Mexico, there is a strong nationalist presence that demands the state have more control over mineral resources. Issues around resource policy became more prevalent during the pandemic, where resource and capital uncertainty pushed some nations to pursue more nationalistic agendas in regards to their resources.

The overall picture of resource nationalism seems to be a positive one, with countries that nationalised seeing a rise in revenue and infrastructure, with the latter being more important to allow for future economic expansion. Other nations have also moved to introduce resource bans. The move to curb artisanal mining has proven to be a positive one, but it could potentially fuel a rise in global prices and lead to more intense resource competition.

There also are other potential complications that arise from resource nationalisation. In particular, the example of the DRC is one to be cautious of for prospective nations. After implementing their new Mining Code in 2018, the government gained more power to tax and intervene in the mining industry. This led to increased taxation, intervention and corruption as the government became more involved in the mining industry. This was seen when the Congolese government suddenly began revoking permits for mining projects, which resulted in a drop in activity and even legal action in the case of Sundance Resources.However, it should be noted that this did little to slow the creation of new mining ventures or operations, with the government granting 3053 different mining-related permits. In addition, the value of exports have risen since the law was implemented, showing that despite the challenges faced by the law, companies are still willing to engage in activity in the region.

Resource nationalism is gaining more popularity and continues to be a tested source of revenue generation for nations that are already invested in mining and metal industries. With current trends, it would stand to reason that resource nationalism could spread to soft commodities, as states look for ways they can expand their revenue and infrastructure more passively through legislation and private market action.

India’s Lithium Rush: Supply Chains, Clean Energy, and Countering China

The discovery of vast lithium deposits in the Indian territory of Jammu and Kashmir is being hailed as a win for the country’s clean energy transition. With the government already promoting domestic EV manufacturing, this could prove to be one of the missing pieces for the puzzle of an Indian EV supply chain.

Background

With rising demand for portable electronics and a push for a low-carbon future, lithium has become one of the most important minerals. Given its application in lithium-ion batteries, it is vital for powering everything from electric vehicles and portable electronics to stationary energy storage systems.

In particular, Lithium-ion battery demand from EVs is set to rise sharply, from the current 269 gigawatt-hours in 2021 to 2.6 terawatt-hours (TWh) per year by 2030 and 4.5 TWh by 2035. According to BloombergNEF’s (BNEF) Economic Transition Scenario (ETS) – which assumes no additional policy measures – global sales of zero-emission cars will rise from 4% of the global market in 2020 to 70% by 2040. Consequently, the global supply chain for lithium has become increasingly important.

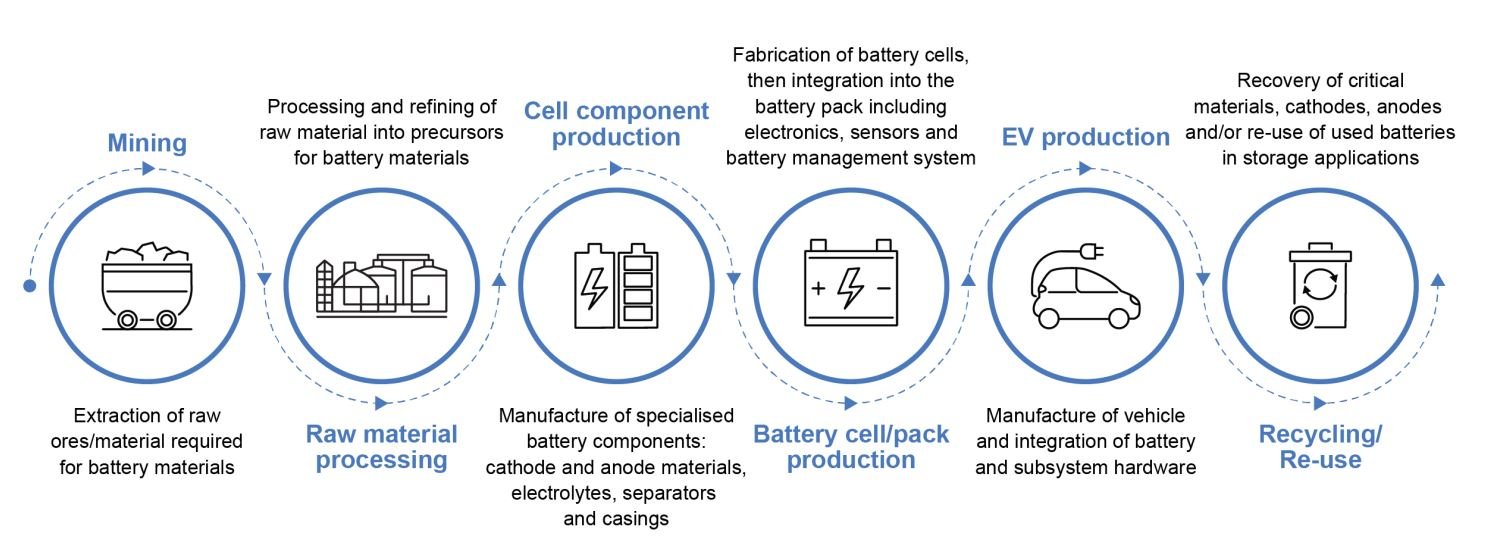

EV battery supply chain. Image credit: International Energy Agency

The lithium supply chain is complex, involving multiple stages and players, and is subject to geopolitical and economic factors. Most of the world’s lithium deposits are in the ‘Lithium Triangle’ of the world in South America – Chile, Argentina, and Bolivia. Of these three, however, only Chile Ranks amongst the list of the world’s top lithium producers, headed by Australia. Apart from production, China dominates both the refining and battery manufacturing in the EV battery value chain.

Source: Statista

India: The New Potential Partner of the World

Given the global geopolitical environment, singular dependence on China for a vital resource such as lithium has far-reaching strategic implications. Naturally, democratic nations across the world are prioritizing the reconfiguration of their supply chains for critical manufacturing inputs. Combining its demographic dividend, educated and sufficient workforce, and entrepreneurial spirit– India is rising as a potential and reliable partner. The European Union’s ‘China + 1’ strategy, the EU-India Trade and Technology council, the United States’ recent Initiative for Critical and Emerging Technologies (iCET), and Australia’s Economic Cooperation Trade Agreement with India – testify to the merit that the liberal-democratic world order sees in a partnership with India.

In the given friend-shoring environment that India enjoys, the recent discovery of 5.9 million tons of lithium in the country is monumental. India’s automobile sector itself is transforming. According to NITI Aayog, by 2030, 80% of two and three-wheelers, 40% of buses, and 30 to 70% of cars in India will be EVs. The newly found lithium can help the nation meet rising demand, both domestically and globally. India’s government has already been pushing for electric mobility and domestic EV manufacturing. The 2023-24 Union Budget, allocated INR 35,000 crore for crucial capital investments aimed at achieving energy transition, including efforts for electrification of at least 30% of the country's vehicle fleet by 2030 and net-zero targets by 2070. For EV manufacturers, the government has launched initiatives such as the Faster Adoption of Manufacturing of Electric Vehicles Scheme – II (FAME – II), allocating approximately $631 million towards subsidizing and promoting the adoption of clean energy vehicles.

Indian Lithium deposits: Risks and Challenges

The recent discovery in the Reasi district of the Union territory of Jammu and Kashmir solves one of the major challenges to a localized li-ion battery supply chain in the country– access to lithium deposits. However, there are more challenges ahead.

Firstly, the Reasi district is just 100 kilometres from the Rajouri district, a geopolitically sensitive area. Although today these areas are well-connected to India with proper infrastructure, including airports and highways, the Line of Control between India and Pakistan is less than 100 kilometres from Rajouri and around 200 kilometres from Reasi. The region’s proximity to Azad Jammu and Kashmir also makes it vulnerable to militant activities. Greater infrastructural development in the region, including a robust logistics network will have to be developed to ensure an uninterrupted indigenous supply chain (given that other stages of the supply chain are also established domestically).

Secondly, although the Geological Survey of India (GSI) has the capacity to discover and locate lithium deposits, the remainder of the value chain to produce commercial-grade lithium indigenously is not in place. Similar to Australia, Canada, and China, the identified lithium reserves in India are in hard rock formations. In order to extract the resource, mining capabilities will first have to be established in the region. It is still unclear whether these reserves will be managed by state authorities or undertaken by the central government, given the strategic importance of the resource. Furthermore, whether the mines be auctioned, like India’scoal mines, or entrusted to a public sector enterprise, is not yet known.

Timely and major investment in developing refining, processing, and purification technologies will be required. India will have to build a large-scale capacity for transforming extracted material into high-purity lithium in order to take full advantage of this discovery. While the opportunity is considerable, so are the costs. India’s government will need to devise a clear strategy that effectively helps both the country’s energy transition and domestic manufacturing ambitions.

Image credit: Nitin Kirloskar via Flickr

Lithium in Iran: Iranian Gold is Black & White

Iran's Ministry of Industry, Mine, and Trade has declared that a significant discovery of 8.5 million tonnes of lithium has been made in Qahavand, Hamadan. The discovery puts Iran in possession of the largest lithium reserve outside of South America. Furthermore, the Ministry has indicated that there could be even more significant amounts of lithium to be discovered in Hamadan in the future. These developments position Iran to potentially overtake Australia as the top supplier of lithium in the world, although it will be heavily reliant on Iran's diplomatic trajectory.

Background

Lithium is widely referred to as "white gold", similar to petroleum being “black gold”, and is a critical element in the shift towards green energy. It serves as a fundamental component in lithium-ion batteries, the primary energy storage system in electric vehicles (EVs). While lithium-ion batteries have been employed in portable electronic devices for several years, their use in EVs is growing rapidly. By 2030, it is anticipated that 95 per-cent of global lithium demand will be for battery production. However, the price of lithium has been declining for several months, and the recent discovery of Iran's reserve is expected to continue this trend. The extent of the impact on global markets will depend on Iran's ability to export and their production capacity.

Iran's economy is facing significant challenges due to a combination of domestic and international factors. The country has been under severe economic sanctions from the United States since 2018, which has severely impacted its ability to trade with other countries and access the global financial system. The ongoing protests and civil unrest have also taken a toll on Iran's economy. Inflation has been a major problem in Iran, with the annual inflation rate reaching over 40% in 2022. This has led to a decline in the purchasing power of the Iranian currency, the rial, and made it difficult for many Iranians to afford basic necessities.

Analysis

Given Iran's current domestic instabilities, the new find will likely be used as a tool to stabilise the Rial (IRR) which is especially volatile due to international sanctions adversely impacting the country and international political disputes, like the developments linked to the JCPOA. However, as extraction is not planned to begin till 2025, there will not be any real direct short-term economic relief; the government will have to rely on the market’s reaction to future potential.

The discovery will also have diplomatic and foreign policy implications. According to IEA projections, the concentration of lithium demand will be in the United States, the European Union and China. Iran can leverage the necessity of lithium supply to the energy transition and net-zero emission goals as a bargaining chip in future negotiations with Western powers over sanctions relief and its nuclear activities. Iran's growing and diversifying portfolio of essential commodities is a potential threat to those pushing for its exclusion from global trading networks. The new discovery can even act as a catalyst for Iranian membership in BRICS.

China has long-standing economic and political ties with Iran, even amidst Western sanctions. China has been a significant importer of Iranian oil, and in recent years, they have invested heavily in Iranian infrastructure and other sectors. With the discovery of a large lithium reserve in Iran, China is primed to take advantage of its relationship to further pursue its trade interests for rare earth minerals. This could further strengthen the economic ties between the two countries, and also create a new avenue for diplomatic relations. However, the relationship between China and Iran is not without its complications. China's increasing involvement and improved relationship with Iran's regional rivals such as Saudi Arabia has raised concerns in Tehran.

Despite these challenges, the potential economic benefits of the lithium discovery in Iran are significant enough that China is likely to overlook some of these complications and Iran can strengthen its diplomatic ties with political powerhouse. The demand for lithium is expected to increase exponentially in the coming years, particularly in China, which has set ambitious targets for the adoption of electric vehicles. Therefore, the availability of Iranian lithium could be a significant boost to China's domestic EV industry.

Powering the future: Lithium in the EV battery value chain

Powering the future: Lithium in

the EV battery value chain

This research paper is the first in a series covering the numerous risks associated with electric vehicle (EV) battery production. Each paper delves into a specific mineral that is vital to this process, starting off with lithium. This series is brought by a team of analysts from the Global Commodities Watch.

Africa in the “white gold” rush

The global supply of lithium ore has become an increasingly tangible bottleneck as many countries move towards a green transition. The International Energy Agency (IEA) predicted that the world could face a shortage of this key resource as early as 2025, as demand continues to grow. The increasing popularity of electric vehicles (EVs), which saw sales double in 2021, as well as other products which require lithium batteries, have been primary factors in this supply crunch.

Demand for lithium (lithium carbonate in this case) has driven high prices, which also nearly doubled in 2022, over $70,000 a tonne, and put pressure on the mining industry to increase production. This has led to heightened competition over this strategic resource and a rush to explore new reserves. An emerging arena in this competition has been Sub-Saharan Africa which has the potential to become a major player in lithium production, behind already established producers in South America and Australia. This region does, however, pose a unique set of challenges for lithium production in terms of infrastructure as well as a diverse and risk prone political constellation.

Within the region there are several countries which have already been tapped as potential producers or have already developed some degree of extraction capacity. Among these are Mali, Ghana, the DRC, Zimbabwe, Namibia and South Africa, at this stage most of these countries are at some stage of exploration, development or pre-production, currently only Zimbabwean mines are fully operational.

The political instability in some of these countries is a primary concern in the future of lithium production. Mali stands out in this regard with the withdrawal of the French intervention force in 2022, after nearly 10 years, and the ensuing power vacuum. In other countries such as the DRC political risk has been largely tied to corruption in governance which limits competition potential as well as human rights and environmental concerns which emerged around cobalt mining.

Zimbabwe offers a perspective into the most developed lithium operation in the region. In early 2022, Zimbabwe’s fully operational Bitka mine was acquired by the Chinese Sinomine Resource Group. Also in 2022, Premier African Minerals, the owners of the pre-production stage Zulu mine, concluded a $35 million deal with Suzhou TA&A Ultra Clean Technology Co. which was set to see first shipments in early 2023. This was followed by a similar $422 million acquisition of Zimbabwe's second pre-production mine Arcadia by China’s Zhejiang Huayou Cobalt.

Zimbabwe’s government responded to this mining boom by banning raw lithium exports stating that “No lithium bearing ores, or unbeneficiated lithium whatsoever, shall be exported from Zimbabwe to another country.” This move is intended to keep raw ore processing within the country, and despite initial appearances will not apply to the Chinese operation, whose facilities already produce lithium concentrates. Yet, this policy does demonstrate the active role that the government is able to play in the market, and their willingness to harness this economic windfall.

Even the most developed lithium mining operations in the region must pay close attention to the political situation unfolding around them. As competition over this strategic resource becomes more acute, the role of soft power will likely play a key role in negotiating favourable terms and preferential treatment in the exploitation of lithium reserves.