The U.S. LNG Pause: Implications for the Global Fertiliser and Food Markets

Peter Fawley

The U.S. LNG Pause

On January 26, the Biden administration announced a temporary pause on approvals of new liquified natural gas (LNG) export projects. The pause applies to proposed or future projects that have not yet received authorisation from the United States (U.S.) Department of Energy (DOE) to export LNG to countries that do not have a free trade agreement (FTA) with the United States. This is significant as many of the largest importers of U.S. LNG–including members of the European Union, the United Kingdom, Japan, and China–do not have FTAs with the United States. Without the DOE authorisation, an LNG project will not be allowed to export to these countries. The policy will not affect existing export projects or those currently under construction. The Department of Energy has not offered any indication for how long the pause will be in effect.

This pause will have political and economic implications across the globe, and is expected to apply further pressure to the LNG market, fertiliser prices, and agricultural production. The following analysis will first delve into the rationale for the pause, the expected impact it will have on global LNG supplies, and the associated risks this poses for the fertiliser and food markets. It will then examine the impact of this policy change on India’s agricultural sector, given that the country is heavily reliant on LNG imports to manufacture fertilisers for agricultural production. The article will conclude with brief remarks about the pause.

Reasons for the Pause

According to the Biden administration, the current review framework is outdated and does not properly account for the contemporary LNG market. The White House’s announcement cited issues related to the consideration of energy costs and environmental impacts. The pause will allow DOE to update the underlying analysis and review process for LNG export authorisations to ensure that they more adequately account for current considerations and are aligned with the public interest.

There are also likely political motivations at play, given the upcoming election in the United States. Both climate considerations and domestic energy prices are expected to garner significant attention during the lead up to the 2024 U.S. presidential election. The Biden administration has been under increasing pressure from environmental activists, the political left, and domestic industry regarding the U.S. LNG industry’s impact on climate goals and domestic energy prices. In fact, over 60 U.S policymakers recently sent a letter to DOE urging its leadership to reexamine how it factors in public interests when authorising new licences for LNG export projects.

These groups have argued that the stark increase in recent U.S. LNG exports is incompatible with U.S. climate commitments and policy objectives, as the LNG value chain has a sizeable emissions footprint. Moreover, there is a concern about the standard it sets for future policy. An implicit and uncontested acceptance of LNG could signal that the U.S is wholly committed to continued use of fossil fuels as an energy source, leading to more industry investments in fossil fuels at the expense of renewable energy technologies. In an unusual political alliance, large U.S. industrial manufacturers are lobbying alongside environmentalists to curb LNG exports. These consumers, who are dependent on natural gas for their manufacturing processes, worry that additional LNG export projects will raise domestic natural gas prices. Therefore, the pause may then be interpreted as an acknowledgement of these concerns and an attempt to reassure supporters that the Biden administration is committed to furthering its climate goals and securing lower domestic energy prices.

Impact on LNG Supplies

Since the pause only pertains to prospective projects, there will be no impact on current U.S. LNG export capacity. However, the pause may constrain supply and reduce forecasted global output as the new policy indefinitely halts progress on proposed LNG projects that are currently awaiting DOE authorisation. In the long-term, this announcement has the potential to tighten the LNG market, potentially resulting in increased natural gas prices and other commercial ramifications. Because the U.S. is currently the world’s largest LNG exporter, a drop in expected future U.S. supplies may force LNG importers to seek to diversify their supply. Some LNG buyers will likely redirect their attention to other, more certain sources of LNG, such as Qatar or Australia. Additionally, industry may be more keen to invest in projects in countries that have less regulatory ambiguity related to LNG projects.

Risk for the Global Fertiliser and Food Markets

Natural gas is key to the production of nitrogen-based fertilisers, which are the most common fertilisers on the market. With regard to the use of natural gas in fertiliser production, most of it (approximately 80 per cent) is employed as a raw material feedstock, while the remaining amount is used to power the synthesis process. Farmers and industry prefer natural gas as a feedstock as it enables the efficient production of effective fertilisers at the least cost.

The U.S. pause on new LNG projects is an unsettling signal to already fragile natural gas markets given the existence of relatively tight current supplies and a forecasted shortfall in future supply levels. This announcement will exacerbate vulnerabilities and put increased pressure on global supplies, potentially leading to greater volatility and price escalation. Additionally, increased global demand for natural gas will further strain the LNG market. Therefore, global fertiliser prices may increase given that natural gas is an integral input in fertiliser production. Natural gas supply uncertainty stemming from the U.S. announcement may not only impact market prices for fertiliser, but could also increase government subsidies needed to support the agricultural industry to protect farmers from price volatility. Due to the increased subsidy outlay, government expenditure on other publicly-funded programs could plausibly be reduced.

The last time there was a significant shock to the natural gas market, fertiliser shortages and greater food insecurity ensued. Following the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine, there was a stark increase in natural gas prices, which led to a rise in the cost of fertiliser production. This prompted many firms to curtail output, causing fertiliser prices to soar to multi-year highs. Higher fertiliser costs will theoretically induce farmers to switch from nitrogen-dependent crops (e.g., corn and wheat) to less fertiliser-intensive crops or decrease their overall usage of fertilisers, both of which may jeopardise overall agricultural yield. Given that fertiliser usage and agricultural output are positively correlated, surging fertiliser costs in 2022 translated into higher food prices across the world. While inflationary pressures have subsided in recent time, global food markets remain vulnerable to fertiliser prices and associated supply shocks. This is especially true for countries that are largely dependent on their agricultural industry for both economic output and domestic consumption. Food insecurity and global food supplies may also be further constrained by unrelated impacts on crop yields, such as extreme weather and droughts.

Case Study: India

The future LNG supply shortfall and its impact on fertiliser and food markets may be felt most acutely by India. The country is considered an agrarian economy, as many of its citizens – particularly the rural populations – depend on domestic agricultural production for income and food supplies. Fertiliser use is rampant in India and the country’s agricultural industry relies heavily on nitrogen-based fertilisers for agricultural production. With a steadily rising population and a finite amount of arable land, expanded fertiliser usage will be necessary to increase crop production per acre. As a majority of India’s fertiliser is synthesised from imported LNG, the expected increased demand for fertiliser will necessitate more LNG imports.

LNG imports to India are projected to significantly rise in 2024, with analysts forecasting a year-on-year growth of approximately 10 per cent. Over the long-term, the U.S. Energy Information Administration predicts that overall natural gas imports to India will grow from 3.6 billion cubic feet per day (Bcf/d) in 2022 to 13.7 Bcf/d in 2050, a 4.9 per cent average annual increase. The agricultural industry is a substantial contributor to this growth. This trend is only expected to continue, as India has announced that it plans to phase out urea (a nitrogenous fertiliser) imports by 2025 in order to further develop its domestic fertiliser industry. To ensure adequate supplies for domestic urea production, India is expected to increase its natural gas demand and associated reliance on LNG imports. A recent agreement between Deepak Fertilisers, a large Indian fertiliser firm, and multinational energy company Equinor exemplifies this. The agreement secures supplies of LNG (0.65 million tons annually) for 15 years, starting in 2026.

Concluding Remarks

The U.S. pause on new LNG export facilities will have ramifications for the global natural gas market and supply chain. While current export capacity will not be jeopardised, the policy change will delay future projects and may put investment plans into question. The pause will also have implications for downstream markets in which natural gas is an important input, such as the fertiliser market. There are a couple of questions that now loom over the LNG industry: (1) what will be the duration of the pause; and (2) to what extent will the pause affect LNG markets?

While the U.S. Department of Energy has given no firm timeline for the pause, analysts estimate – based on previous updates – that the DOE review will likely last through at least the end of 2024. The expectation is that the longer the pause remains in effect, the more uncertainty it will create, especially as it relates to private industry investment decisions and confidence in U.S. LNG in the long-term. In addition to the fertiliser and food markets, transportation, electricity generation, chemical, ceramic, textile, and metallurgical industries may all be affected by the pause. One potentially positive consequence is that because LNG is often thought of as a transitional fuel (between coal and renewable energies), a large enough impact on LNG supplies could accelerate the energy transition directly from coal to renewable sources of energy, providing a boost to the clean energy technologies market. However, the pause may also create tensions with trading partners as it could be interpreted as an export control or a discriminatory trade practice, both of which stand in violation of the principles of the multilateral rules-based trading system. This may expose the U.S. to potential challenges and disputes at the World Trade Organization. Although it may be some time before we are provided concrete answers to these questions, the results of the 2024 U.S. presidential election will provide some insight into what LNG policies in the U.S. will look like going forward.

The King’s Gambit: The Opportunities and Risks of Israeli Approval of Gaza’s Offshore Gas Extraction

On 18 June 2023, Israel’s prime minister, Benjamin Netanyahu, announced that his country had given the green light to the Palestinian Authority’s (PA) development of a natural gas field off the coast of the Gaza Strip. Given the strained relations and recurring rounds of violent escalation between Israel and militants in Gaza, such a move is not straightforward and must be explained with reference to the political, economic and security interests of the parties involved.

Israel’s interests

To the outside observer, a concession to the Palestinians by an Israeli government broadly seen as the country’s most right-wing ever may be surprising. Yet it is an enduring fact that Israel’s most bold overtures to its neighbours have been carried out by the right wing. It was Menachem Begin’s Likud government that exchanged the Sinai Peninsula for a peace treaty with Egypt in 1979. Karine Elharrar, Israel’s Energy Minister under Israel’s previous, more centrist government related that she had been approached with the Gaza gas proposition toward the end of 2021 but ruled it out as unfeasible as her government was already under fire from the then-Netanyahu-led opposition for its pursuit of a maritime gas deal with Lebanon. The reason Israeli public opinion considers giveaways by the right more palatable is the impression that they have been vigorously negotiated over and, if made, must be squarely in the national interest. The logic here follows from the Israeli-Lebanese precedent: give your enemy something to lose, and they will think twice before risking all-out conflict.

The Israeli right has long opted for ‘managing’ the Israeli-Palestinian conflict over solving it. A recent, pressing challenge to this strategy has been the gradual disintegration of the PA, the governmental body created by the 1993 Oslo Accords and charged with governing the Palestinian Territories. It lost control of Gaza to Hamas after the latter’s violent takeover of the strip in 2007 and its legitimacy among the West Bank’s population has been undermined by accusations of corruption, mismanagement, and collaboration with Israel. Israel hopes the deal will shore up the PA, an important security partner in preventing and punishing local terrorist attacks, by bringing much-needed funds and restoring its image as a responsible, effective authority.

Nevertheless, Israeli leaders do not harbour any illusions about the fact that some of the revenue generated by the gas sales is bound to end up in the hands of Hamas, a militant group designated by it, the US, the EU, and many others as a terrorist organisation. This is widely seen as the reason for the stalling of the initiative since it was first proposed in 1999. Recently, however, experts have suggested that Israel intended the concession as a quid-pro-quo for Hamas’s acquiescence over its military campaign against the Palestinian Islamic Jihad (PIJ) in May 2023. Such an approach attempts to gain Hamas’s cooperation through a carrot-and-stick strategy.

Gaza’s interests

On Gaza’s side, the foremost imperative is economic. Years of economic blockade by Israel and Egypt, alongside local mismanagement have turned Gaza into what certain human rights organisations have called an ‘open-air prison’. Its 2.3 million inhabitants experience power cuts for up to 12 hours a day, a result of an over-dependence on a small local oil-fuelled power plant and insufficient Israeli electricity. Meanwhile, the Gaza Marine field is thought to hold almost 30 billion cubic metres (1 trillion cubic feet) of natural gas. If tapped, this source would be more than enough to cover the area’s estimated 500-megawatt daily requirement, with the remainder piped into liquefaction units in Egypt and sold on global markets, yielding billions of dollars in revenues.

If such a plan materialises, both the PA and Hamas will seek to claim credit. The PA will attempt to win back its support in Gaza and the West Bank as a government that secured economic development and raised living standards through internationally negotiated agreements. Hamas, for its part, would build on its credentials not only as a force of resistance to Israel but as a provider of economic and social benefits in the strip, potentially facilitating its formal consolidation in the West Bank too.

Risks

Progress on an Egyptian-mediated agreement on gas by Israel and the PA faces three principal risks.

First, and most obviously, the breakout of a new round of violence between Israel and Hamas, possibly, but not necessarily, as part of a broader regional escalation (e.g. involving clashes across the Israeli-Lebanese border) will likely cause Israel to take the deal off the table. Israel’s leadership must convince itself, and its supporters, that it is not arming its enemies.

Second, Israel is counting on Egypt to act as a guarantor and third-party stakeholder in securing Hamas’ continued cooperation and underwriting its good behaviour. Yet while Egypt has proved an indispensable mediator in this regard over the last decade, it is unclear how much sway it holds over the militant organisation in comparison to Iran, its chief ally and financial backer. Given the Israeli-Iranian geopolitical archrivalry, it is not straightforward to assume that Hamas is either willing or able to peacefully coexist with Israel for long.

Third, and finally, the recent political turmoil in Israel as a result of the judicial reforms introduced by Netanyahu’s coalition might complicate his efforts to justify the move to his supporters. If the coalition eventually backs down from the reforms demanded by its hard-line elements and supporter base, the addition of a formal concession to the Palestinians may become even harder to stomach, especially after Netanyahu himself had opposed Israel’s previous deal with Lebanon as a ‘surrender to terror’.

The next step

Full-scale extraction of natural gas from the Gaza Marine field will require the PA to obtain a final agreement designating the status of the field in which Israel will relinquish any remaining claims to the reservoir. Israel’s apparent green light for the project could bolster the economic prospects for the strip, and may succeed in furthering regional stability, as its proponents hope. If successful, the project and its Israeli-Lebanese predecessor of last year may illustrate the opportunities for opposing states of leveraging the relative ambiguity and lesser politicisation of maritime boundaries to reach compromises in spite of intransigent public audiences. Nevertheless, the multiplicity of actors involved, with their limited power and often conflicting interests, means the project is fraught with risks that threaten to turn it into another false start in a troubled political relationship.

Image credit: Bureau of Safety and Environmental Enforcement (BSSE)

North African Energy Market Analysis: Algeria

This report serves as an overview of the risks – mainly political, economic, social – in the Algerian energy market. It will look at natural gas, as well as crude oil and green energy. The report is also part of a broader series of analyses on North African energy markets.

Central and Eastern European countries are well-prepared for the next 2023/2024 heating season, but risks still loom large

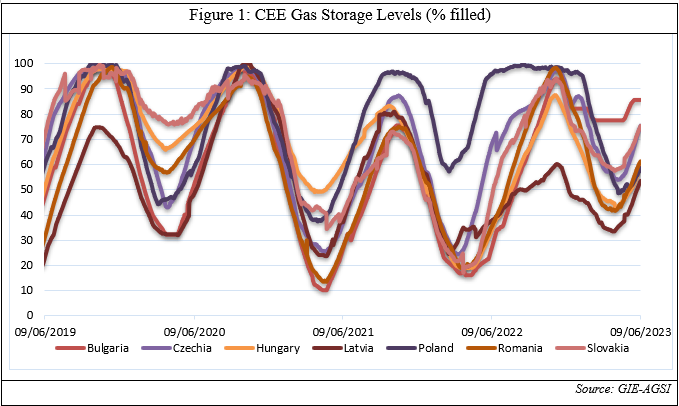

Central and Eastern European (CEE) countries are well-prepared for the next 2023/2024 heating season, despite the presence of moderate risks. This is due to two factors. Their strategies to diversify from Russian gas have been overall successful, and current gas storage levels are high. As of June 2023, they are considerably higher than in the same period last year. While at the beginning of June 2023 they amounted to an average of 49%, nowadays storage facilities are filled between 53.5% (Latvia) and 85.6% (Bulgaria). What emerges is a positive situation with regard to the CEE’s energy security in winter 2023/2024. Indeed, according to the EU Gas Storage Regulation (EU/2022/1032), to ensure reasonable gas prices in the next heating season, EU countries have to reach a storage level of 90% before October 2023. Considering that all CEE states have achieved the intermediate targets for May set out in the regulation and that they still have the entire summer to build up their gas storage facilities, they will likely reach the EU-mandated level of 90% before next winter.

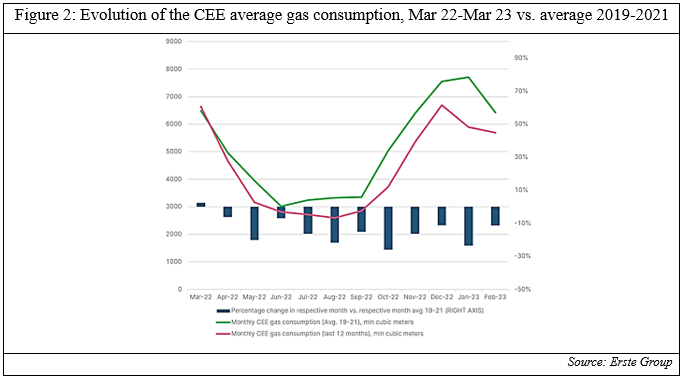

Moreover, the CEE states have also reduced their vulnerability to Russian gas by reducing their total demand for natural gas and diversifying their suppliers. When looking at the gas consumption in the region over the last 12 months as opposed to the average between 2019 and 2021, it can be noted that it decreased by 14% -more than the Eu average reduction of 11%- with a more visible decline taking place since mid-2022 [Figure below]. At the same time, they also diversified the remaining gas imports away from Russia, importing natural gas from Scandinavian countries (especially Norway) and LNG from overseas, including the US. In this regard, CEE countries were supported by the construction, ahead of the 2022/2023 heating season of several gas interconnectors, i.e., physical infrastructure systems that enabled natural gas transportation from other European countries. All these factors allowed the CEE to reduce its dependence on Russia.

In 2022, the IMF estimated that a potential Russian gas supply shut-off would have led to a GDP output loss of an average of 2.8%, compared to an EU average of 2.3%. In the short term, Hungary, the Slovak Republic and Czechia -which were the most vulnerable CEE countries- were expected to experience gas consumption shortages of up to 40% and a potential GDP decline of up to 6%. However, even if later in 2022 Russia did halt its gas supplies to the CEE, the expected gas shortages did not materialise. And while the CEE annual growth rate will slow down to an average of +0.6% in 2023 according to the European Commission, this is still double the expected EU average 2023 growth, and the output losses were considerably less than what was projected a year earlier by the IMF. In other words, countries in the region have so far proved to be economically resilient.

Nevertheless, the CEE still faces challenges regarding its energy security. Mainly, this relates to the steep surge in energy prices in the region following Russia’s weaponisation of gas supplies to the EU. After Gazprom unilaterally changed the terms of its gas supply contracts demanding payments in rubles, it halted all supplies to Poland and Bulgaria, which refused to pay according to the new rules. Even if Slovakia, Czechia and Hungary agreed to pay in rubles, Russian gas flows were anyway gradually stopped. First, Russian supplies through the Yamal pipeline ceased in May 2022, then, gas in transit through Ukraine also significantly decreased. Lastly, in August 2022 Moscow completely stopped the Nord Stream 1 pipeline. To date, the main way Russian gas flows to Europe is via the TurkStream route (which however supplies only Hungary and Serbia). The other is the Ukraine route, but this is likely to reduce in the coming months. As a result, energy prices in the region rose substantially, affecting especially energy-intensive industries. In 2022, producer energy prices increased by 93%. Coupled with the increase in inflation and the decision by CEE central banks to raise their policy interest rates, the increase in energy prices led to a surge in the production costs of CEE industries. As the CEO of Volkswagen Thomas Schafer claimed “Europe is not cost-competitive in many areas, in particular, when it comes to the costs of electricity and gas”. As a result, CEE energy-intensive manufacturing firms cut energy consumption and jobs, while substituting their own production with cheaper energy-intensive imports. Even if currently energy prices have decreased, there is the possibility that they will rise again next winter, when energy demand will rise again.

The overall situation of the CEE with regard to its energy security is positive, since storage facilities in the region have reached an adequate level, and the CEE has reduced its dependence on Russia. However, CEE countries have to ensure energy price stability for their industrial sector. This is especially important in view of the upcoming winter, when energy demand will rise again. In order to avoid such a scenario, CEE countries have to increase their diversification efforts to expand the number of reliable gas suppliers. This will not be an easy task, especially for landlocked states in the region such as Hungary and Slovakia.

The Piano Mattei lands in Brazzaville: A Look at Italy's Latest Quest for Energy Security.

On 25 April 2022, Italy moved one step further in consolidating its energy diplomacy across Africa. After securing gas deals in Libya, Morocco and Algeria, the state-owned energy group Ente Nazionale Idrocarburi (Eni) signed a US$ 5 billion deal gas liquefaction project with the Republic of Congo, from whom it had previously acquired the Tango FLNG liquefaction station in early August of 2022. Together, the facilities make up the Marine XII joint venture project along with 31 drilling wells, 10 platforms and 1 gas pre-treatment plant logistically integrated off the shores of Pointe-Noire.

Eni has been the flagship of Rome’s new foreign policy towards Africa dubbed as the Piano Mattei, initiated by Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni as a strategy to reduce dependency on Russian gas imports by projecting its influence just below the Mediterranean Sea. Since the Piano could be pivotal for the EU to fulfil its energetic security objectives (as we previously discussed in this must-read Spotlight!), this article identifies key drivers of risk and success emerging from Eni’s new undertaking in the Republic of Congo and what is its contribution to Italy’s greater energetic security planning.

How Eni did it: Managing Political Risk in Congo

After almost 60 years in Congo, one could expect that Eni would have nurtured an engagement with the country’s most influential stakeholders in order to create an identity of interest that would later pay off as the company’s most competitive aspect to secure the resilience of its business. Interestingly, Congolese law largely centralizes the administration of oil and gas exploration projects - including the issuance of permits, renewal of contracts, and local content requirements - under the Minister of Hydrocarbons’ authority and discretion. Minister Bruno Jean-Richard Itoua, the current incumbent, not only oversaw the signing of the new LNG project but actively supports it as a potential driver of Congolese economic growth and energy self-sufficiency. Such good deeds bode well for the project's stability and are likely to work as a preemptive measure against any major regulatory disruption for the foreseeable future.

The Republic of Congo’s stable relations with Italy, the European Union and major continental powers such as France are also likely to play a stabilizing and supportive role in the operation as they currently show little signs of major degradation, even if thorny issues such as corruption, autocratic practices, and environmental degradation should be kept on a close watch for precaution’s sake.

On the other hand, the majority of installations comprising the Marine XII project - including the ones designed to export liquefied gas - are located on the Gulf of Guinea where piracy activities targeting cargo ships happen, thus remaining a relevant risk to be observed along with the possibility of criminal violence against foreigners in Pointe-Noire. Whether Eni's previous incidents in Nigeria will foster greater investment in maritime security against piracy remains something to be seen.

Was it really all for nothing?

Despite positive outlooks, Eni’s new undertaking in Congo is likely to do little for Italy’s energy security. Congo’s LNG production is expected to reach a peak of 4.5 billion cubic meters per year by 2025, which would only correspond to roughly 6.5 per cent of Italy’s total LNG imports in 2022. More broadly, the experience is telling of Piano Mattei’s fundamental weakness of over-pulverizing supply among possibly more reliable sources while still relying on other major individual actors.

Figure 1: Share of Italy’s Natural Gas Imports by Country (2010-2021). Based on data compiled by the Ministry of Environment and Energy Security (2021),

For example, in 2020, it would take the combined gas supply of 4 countries (Netherlands, Libya, Netherlands and Qatar) to match Algeria’s participation totalling 24 per-cent in that year. While it should be recognized that Russia’s participation suffered sharp drops in 2022 and that logistical impediments could certainly hinder alternative solutions, data seems to indicate that Piano Mattei's current supply diversification strategy currently seems more like a substitution: by trading Moscow for Algiers, Rome’s new diplomatic undertaking might still be falling short of its ambitions. Nevertheless, the pursuit of risk hedges could be recognized.

Since Meloni has veiledly thrown her support behind Algeria on the Western Sahara conflict before, further signs of support in this and other issues could indicate an appeasement with Algeria for the short term. Likewise, the share of renewable energy consumption consistently grew from 2018 to 2021 as well as their participation in Italy’s total energy consumption, despite still accounting for the smaller share. Thus, in the long term, the return of investment flows to renewables production capacity could become pivotal for Italy to achieve its desired - and fiercely pursued - energetic security.

All eyes on Algeria: how natural gas is shaping North-African politics

One country in North-Africa seems to be making the most out of the current energy crisis and a new era in great-power rivalry - Algeria. Great potential has fuelled massive interest in the country’s gas industry and led to a significant increase of gas revenues in the past years. As a consequence, the country is able to spend big, both domestically and abroad, and charter a more active foreign policy. The latter, however, is held under increased scrutiny by parliamentarians and senators across the Atlantic, raising questions about the risks of Algerian gas imports. Another question, which is worth asking, is to what extent Algerian gas potential can be turned into actual export flows.

This analysis will take a deep-dive into 1) the drivers of increased interest and cooperation in Algeria, 2) the outcomes so far, and 3) complications and geopolitical dynamics, after which a small outlook will be presented.

Drivers of increased interest and cooperation in Algeria

Increased interest and cooperation in Algeria and North Africa are partly driven by the war in Ukraine and the need to source new gas supplies. In a bid to curb Russian gas imports, both European and international energy companies are scrambling supplies across the globe. Before the war, Russian natural gas accounted for roughly 45% of EU imports or 155 bcm, whereas it is now standing at roughly 10% of EU imports or 34.4 bcm. That leaves a gap of roughly 120.6 bcm to satisfy demand. And while some supplies may be curbed by lowering demand through the increase of energy efficiency and the usage of other fuels, most will have to be sourced elsewhere.

Algeria, as a source of natural gas, offers much potential. It is Africa’s largest natural gas exporter and in combination with its location, the country could offer an ideal place to source gas. Algeria’s potential has led to increased interests in its gas industry. Other countries in North Africa, including Libya and Egypt, have also received increased interest. Notably, Libya secured an $8 billion exploration deal with Italian energy major Eni.

*Note that the Trans-Saharan and Galsi potential or planned pipelines.

Algerian gas market: Facts and Figures

Reserves: The country holds roughly 1.2% of proven natural gas reserves in the world, accounting for 2,279 bcm.

Production: Its production stands at 100.8 bcm per year.

Exports: In 2021 it exported 55 bcm, 38.9 bcm through pipelines, and 16.1 bcm in the form of LNG. European imports accounted for 49.5 bcm, 34.1 bcm by pipelines, and 15.4 bcm in the form of LNG.

Export capacity: Algeria has a total export capacity of 87,5 bcm: the Maghreb-Europe (GME) pipeline (Algeria-Morocco-Spain) 13.5 bcm, Medgaz (Algeria-Spain) 8 bcm, Transmed (Algeria-Tunisia-Italy) 32 bcm, LNG 34 bcm.

Aside from potential, ambition (on both sides of the Mediterranean) is another reason for interest and cooperation. Interest has come from the EU and several member states, but mostly from Italy. Instead of merely securing gas supplies, Italy aims to become an energy corridor for Algerian gas in Europe. This will boost Italian significance in the European energy market, increasing both transit revenues and investment in its own gas industry. Moreover, Rome seeks to increase its profile in the Mediterranean, mainly to stabilize the region and decrease migration flows. It views both Algeria and its national energy firm Eni as key factors in that aim.

Algeria is also looking for a more active role in the region. For the past years, the country has been emerging from its isolationism, which characterized the rule of president Bouteflika, who was ousted in 2019. With new deals and increased gas revenues it hopes to increase defense and public spending, prop-up its gas industry, which suffered from lack of investment, and stabilize its economy and the region. Aside from economic reasons, therefore, cooperation between the two sides is politically motivated as well.

What has this increased interest and cooperation so far led to?

As a result of increasing gas prices and rising demand, the Algerians have seen their revenues increase massively. Sonatrach, Algeria’s state-owned energy company, reported a massive $50 billion energy export profits in 2022, compared to $34 billion in 2021, and $20 billion in 2020. This will allow for more fiscal space and public spending. In fact, the drafted budget of 2023 is the largest the country has ever seen, increasing 63% from $60 billion in 2022 to $98 billion in 2023. Because of bigger budgets, Algeria will also be able to partly stabilize its neighbors by offering electricity and gas at a discount - something the country is currently discussing with Tunisia and Libya.

The Italian trade looks most promising and has led to multiple deals. Trade between the two countries has doubled from $8 billion in 2021 to $16 billion in 2022, whereas dependence on Algerian gas increased from 30% before the Ukraine war to 40% at the moment. Last year, Eni CEO Claudio Descalzi secured approval from Algeria to increase the gas its exports via pipeline to Italy from 9 bcm to 15 bcm a year in 2023 and 18 bcm in 2024, and last month, Italian Prime Minister Meloni, joined by Descalzi, visited Algeria to build upon that earlier cooperation. Again, two agreements were signed, one with regards to emissions reduction and the other to increase energy export capacity from Algeria to Italy.

The visit and new plans reflected ambitions from both sides. President Tebboune recently announced Algeria’s aim to double gas exports and reach 100 bcm per year and Meloni mentioned a new ‘Mattei plan’ (which refers to Enrico Mattei, founder of Eni, who sought to support African countries' development of their natural resources in order to help the continent maximize its economic growth potential, while facilitating Italian energy security). Furthermore, the Algerian ambassador stated the country’s intention to make Italy a European hub for Algerian gas, whereas Eni CEO Descalzi mentioned the possibility of a north-south axis, connecting the European demand market with the (North) African supply market.

Interest has also led to other plans, potential deals, and rapprochement. Firstly, the EU sees potential and aims to secure Algeria as a long-term strategic partner. Last year, the EU’s energy commissioner visited Algeria as part of “a charm offensive”. Secondly, the Ukraine war and Algeria’s abundance of gas supplies also seems to be the main reason for France’s rapprochement toward Algeria. In addition to this, Slovenia plans to build a pipeline to Hungary to transport Algerian gas as Algeria aims to increase electricity exports to Europe. Algeria’s future as an energy supplier could also go beyond natural gas, as last December German natural gas company VNG signed an MoU with Sonatrach to examine the possibilities for green hydrogen projects. Algeria’s future as a hydrocarbons supplier could also extend beyond Europe as Chevron aims to reach a gas exploration agreement with Algeria and is assessing the country’s shale resources.

Complications & geopolitical dynamics

Translating all that interest and cooperation into more Algerian output, and stable secure supplies for Italy and Europe, on the other hand, is a different story. There are several factors that hamper or complicate the growth of the Algerian gas industry and the potential North-South Axis. Those complications can be divided into two broad groups: (i) industry specific complications and (ii) complex (international) politics.

Industry specific complications

There are specific limitations to the technical feasibility of increasing production. Years of underinvestment, due to corruption, unattractive fiscal terms and a slow bureaucracy, have resulted in less exploration and development of new fields, which roughly take 3-5 years from the exploration phase to production. In combination with decline from maturing fields, this limits industry growth and export potential in the short-term. Internal audits show that Sonatrach can barely mobilize an additional 4 bcm per year, let alone the additional 9 bcm meant for 2024. Doing so will take a bite out of its LNG business, which currently sells for a much higher price. Exploration and development will take time and mostly affect the medium-term in 3-5 years. Furthermore, Algeria has to perform a balancing act between its exports and increasing domestic demand, which is set to grow 50% by 2028.

A North-South axis will require Italy to upgrade its gas network as well. The country will have to establish several energy corridors to demand markets in Europe and expand its domestic gas network, which requires billions of investment. In this light, some analysts point to the fact that claims about such an axis are currently rhetoric and are meant to secure investments that are needed for its own gas industry.

Geopolitics

Geopolitical considerations also may influence gas flows toward Europe. For starters, Algeria has a complicated relationship with Morocco, which according to Algiers, 'occupies’ the Western Sahara. Algeria maintains it is a sovereign territory and in 2021, this row resulted in the suspension of the GME pipeline, which runs through Morocco. While Spanish imports through the Medgaz pipeline increased from 8 bcm to 9 bcm in 2022, the closure of the GME pipeline resulted in an overall decrease of exports to Spain by more than 35%. By using gas (revenues) as a tool of statecraft, Algeria also managed to convince Tunisia in countering Morocco, after handing it economic aid.

The country’s relations with Russia might also complicate gas flows. Its relation encompasses military cooperation, including joint military exercises and weapons purchases. Algeria is the 6th largest importer of weapons in the world and roughly 70% of Algeria’s weapons are sourced from Russia. In 2023, its largest budget draft ever included a rough 130% or $13.5 billion rise in military expenditure and, in November, plans were announced to dramatically increase its acquisition of Russian military equipment in 2023, including stealth aircraft, bombers and fighter jets, and new air defense systems.

With the war in Ukraine, Algeria’s relation with Russia creates a risk of sanctions, with some U.S. senators and EU parliamentarians being particularly vocal on this. As a result of sanction risk, Sonatrach included a clause in its gas contracts, which allows for currency denomination change every 6 months, reflecting warrines of U.S. sanctions and dollar-denominated gas trade. Its recent application to BRICS, will increase the country’s capacity to charter its own foreign policy, without endangering security and trade ties to Beijing and Moscow.

Outlook

Significant rises in Algerian export output, outside of its current commitments, are not likely in the short-term.

Ambitions with regards to a potential North-South axis are largely rhetorical and meant to increase investment and gather broader regional and European-wide support for an energy corridor.

Sanction-risks remain low. Because of Algerian significance to the European gas market, the EU and its member states will likely try to maintain good ties with the North-African country.

The effect of future massive weapons purchases from Russia will likely have a negative effect on relations with the EU, but it is unclear whether that will immediately impact (future) gas flows.

Increasing gas revenues and bigger budgets will decrease the risk of domestic instability. As a consequence, Algeria has the possibility to charter a more active foreign policy - something we are currently already seeing. The main goal of such a foreign policy will be to stabilize its immediate neighborhood.

Risks of the German gas plans

This comprehensive mini-report from the Global Commodities Watch identifies the risks involved with German preparations and plans to curtail Russian gas supplies.