Ghanaian electricity: the triumph of competitive politics over good governance

On 26th May, Ghana’s government tried to propose a restructuring of the US$1.58 billion of debt owed to various private power producers. The producers have rejected this proposal and threatened to cut off the power supply, which could cause a third power crisis within the last decade. These power crises are part of a larger consistent failure to provide basic electricity to the citizens of Ghana; It exemplifies the failure of the International Monetary Fund’s (IMF) Structural Adjustment Programmes (SAP) and the Good Governance Agenda of the 1980s. This article will explore how commercialisation can fail in a culture of competitive politics.

Electricity has been a front-running issue in Ghanaian politics since its founding President Kwame Nkrumah’s belief that building the Akosombo Dam, the third biggest dam in the world in terms of water capacity, would bring developmental leaps. The succeeding presidents including President Jerry Rawlings, the first democratically elected President, used the extension of the electric grid to draw votes, making electricity a critical measure of political success and developing a norm that electricity provision is a core responsibility of the government. This has led leaders to intervene frequently in the privatised energy sector to increase electric grid sizes (making it one of the biggest in West Africa). The political structure also allows the president to have a say in the decisions of the supposedly ‘independent’ Public Utilities Regulatory Commission (PURC) since he has the power to appoint board members. Ghana adopted the IMF’s SAP in 1995 when its inflation rates were over 100%. Under the Standard Reform Model, Ghana allowed private management of their electrical facilities.

Fast forward to August 2012, the anchor of a pirate ship ruptured on the West African Pipeline, inflicting a GDP loss of US$320-924 million. This external element is only the tip of the iceberg. The underlying issue for such a large GDP loss (an estimated 4%) was that the remaining power generation capacity required crude oil, which was more expensive than pipeline gas. This led to high debts within the producing companies; the Volta River Authority (VRA) and the Electricity Company of Ghana (ECG). Furthermore, Government subsidies and financial support were insufficient for these companies to continue ordering fuel, despite multiple requests. For example, The VRA requested amelioration for six cargoes of light crude but was only provided with finance for three. As such, the government played a significant role in the elongation of the crisis. A central problem can be traced back to the inefficiency of Ghana’s large electricity grid. Incumbents often expanded the grid in hopes of demonstrating their continued dedication to providing electricity, but large parts of these grids are unmonitored and suffer from severe reliability issues. This can be traced back to show how competitive politics has compounded the severity of the crisis.. With the 2012 General Elections scheduled for December of the same year,, there was a further electorally motivated intervention to prevent tariff rises, increasing profit and allowing the companies to order more fuel. This resulted in the inability of the VRA to pay the fuel suppliers, thus further elongating the crisis.

Without sufficient investigation into the underlying issues of the price of fuel and the lack of capital to invest in them, the government signed 43 new contracts for primarily thermal power plants taking the total electricity capacity (assuming sufficient fuel is provided) from 1GW to 5GW.. The then President John Mahama did little due diligence and circumvented officials in the Energy Commission who had predicted energy demand of 3,000 to 4,000MW by 2020. The simplest way to mitigate this oversupply would be for Ghana to become an electricity exporter in the region; however, this did not materialise due to high tariffs, poor infrastructure, and neighbouring countries wanting to be self-reliant after previous experiences of shortage. This overabundance has driven government debt to US$1.4 billion, which is approximately 4% of GDP. Furthermore, these contracts were used to create thermal power plants instead of implementing the planned hydropower plants including Micro-Hydro Western Rivers Scheme and the Juale Dam. Focusing on increasing electricity capacity instead of the fundamental cash flow and reliability issues can be best explained as an electorally driven solution which demonstrates the incumbent’s continued dedication to providing electricity by investing in tangible infrastructure instead of actually solving the electricity crisis in the long run.

These two crises show the failure of the Standard Reform Model in a highly competitive political situation. The market mechanism, commercialisation and separation had no effect in a country where governments continue to intervene to meet short-term political objectives. Since tariff increases meant a loss of power, it was impossible for leaders to divert resources to achieve long-term stability and instead focus on unsustainable practices like low tariffs.

Today, Ghana is set to default on loans by the IMF and has been in talks with the G20 to restructure its external debts. While the IMF is imposing more stringent conditions on loans, its leaders have also been cosying up to the Chinese to help solve their debt crisis, leading to increasing tensions with the United States. If this gridlock continues, the Ghanaian people would either be buried in further debt or have to face another electricity shortage crisis.

Cover image: “Ghana Akosombo Dam” by Mark Morgan Trinidad A

Powering the future: Cobalt in the EV battery value chain

Powering the future: Cobalt in the EV battery value chain

This research paper sheds light on the key risks associated with the supply of cobalt, a critical mineral for the production of electric vehicle (EV) batteries. With demand for EVs projected to grow steadily in the coming decade, it is crucial that companies mitigate these risks. The concentration of finite cobalt reserves in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) and the concentration of refining capacities in China create a delicate balance of supply that is highly risk prone.

Powering the future: Lithium in the EV battery value chain

Powering the future: Lithium in

the EV battery value chain

This research paper is the first in a series covering the numerous risks associated with electric vehicle (EV) battery production. Each paper delves into a specific mineral that is vital to this process, starting off with lithium. This series is brought by a team of analysts from the Global Commodities Watch.

REPowerEU, Piano Mattei, and the Political Economy of the Mediterranean

From the Phoenicians to the First French Republic, two shores of the Mediterranean have been the cradle for many important ancient civilizations, including the Carthaginians and Ancient Egyptians. Although in modern times the post-war political alignments and government institutions look very different, the evidence of a rich common history can be seen all over Southern Europe and North Africa in the forms of enclaves, architecture, and shared cultural and linguistic norms. Following Giorgia Meloni’s state visits to Algeria and Libya, this spotlight considers how Italy’s Piano Mattei (Mattei plan) can be an opportunity for the rest of the European Union (EU) to successfully implement the REPowerEU energy plan and potentially rekindle trans-Mediterranean trade and cooperation, beyond natural gas and energy markets.

Immigration, Energy Markets, and Fratelli d’Italia: What is Piano Mattei?

In simple terms, Piano Mattei represents Italy’s de facto foreign policy in the Mediterranean under Giorgia Meloni’s tenure as President of the Chamber of Deputies (the official title of the head of the Italian government). The origins of Mattei can be found in Fratelli d’Italia’s (FdI) manifesto for the 2022 Italian general election, which stresses FdI’s belief that Italy must once again become a leader in energy markets. Piano Mattei takes its name from Enrico Mattei – founder of Italy’s state-owned hydrocarbons agency: Ente nazionale idrocarburi (Eni). During his time in the Chamber of Deputies, and later as Chairman of Eni, Mattei realised that if Italy wanted to include natural gas in its energy mix then Italy needed to cooperate with key exporters. Indeed, Mattei oversaw the signing of various bilateral agreements with many newly-independent states in the MENA region to import natural gas to Italy. Mattei’s work with Eni was also crucial to the construction of the Transmed pipeline, which channels Algerian natural gas to Sicily via Tunisia. The plans for the Transmed pipeline also included the Maghreb-Europe pipeline, which exported Algerian gas to the Iberian Peninsula until last October, when Algiers elected to not renew its export contracts with Morocco over increasing tensions over the Western Sahara conflict. This effectively ceased the flow of natural gas from Algeria to Iberia.

Giorgia Meloni formally introduced Piano Mattei last December, during the eighth iteration of the Dialoghi Mediterranei di Roma – a forum on Mediterranean politics hosted by Italy’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs and International Cooperation alongside the Instituto per gli studi di politica internazionale (ISPI), a prominent Italian thinktank. In Meloni’s own words, Piano Mattei is a “virtuous collaboration leading to the growth of the European Union and African nations” guided by the principles of “interdependence, resilience, and cooperation”. Naturally, the namesake “Mattei” suggests that Meloni’s stance is primarily to secure energy supplies for Italy and totally eliminate the dependence on Russian natural gas. On the one hand, however, Meloni’s foreign policy in the Mediterranean also aims to build upon the European Commission’s trade ambitions with the ‘Southern Neighbourhood’: “The long-term objective of the trade partnership between the EU and its Southern Neighbourhood is to promote economic integration in the Euro-Mediterranean area, removing barriers to trade and investment” and the EU’s wider energy policy goals. On the other hand, Associazione Amici dei Bambini – an Italian children’s rights NGO – raises the concern that Meloni’s ambiguous and rhetorical references to immigration in her keynote speech at the Dialoghi Mediterranei di Roma, suggest that perhaps Meloni’s ambitions are centred on delivering campaign promises regarding trans-Mediterranean migration flows. Indeed, Meloni’s lexical and rhetorical ambiguity is often the cause for concern for some analysts (including the author of this spotlight). Whether Meloni intends to use Mattei to further her immigration policies is difficult to ascertain at this stage, and is beyond the scope of this spotlight.

Regardless of how one may interpret the scope or intentions of Mattei, one thing is certain – it can be an opportunity for all of the Mediterranean countries. For Italy (and to a large extent, Meloni) it would be a first step in re-establishing itself as a regional economic powerhouse and help move away from decades’ long economic stagnation. For Algeria and other North African countries, the prospect of increased cooperation and interdependence with the EU is an incentive for investment, potentially beyond natural gas and energy markets. In the two weeks after Meloni’s visit to Algiers on January 24 2023, Eni’s (Euronext Milan) share price increased 4.58 per-cent from €14.18 to €14.83. Year-to-date growth is around the 8 per-cent mark, at time of writing.

Limits for the European Commission and Meloni’s Government

Although a more collaborative and economically interdependent Mediterranean could have the potential to benefit states on either side, Giorgia Meloni and the European Commission need to learn from the past if they are to derive short-term economic benefit as well as long-term regional cohesion. What is meant here by “learning from the past” is that ‘switching’ who is supplying the EU with gas from Russia to Algeria, for example, does not account for the weakness in Europe’s energy strategy before the Russo-Ukrainian War. That is, relying on a weakly-integrated trade partner for a crucial commodity.

The REPowerEU plan outlines the EU’s energy policy following the Russian invasion of Ukraine. Although the medium to long-term impetus is to increase the role of renewables within the bloc’s energy mix, the short-term imperative includes securing hydrocarbons from non-Russian suppliers. These two foreign policy goals are not necessarily ad diem, and in the context of the Mediterranean, actually involve compromising successful economic interdependence between the EU and its ‘Southern Neighbourhood’.

To contextualise; on January 19 2023 Resolution 2023/2506 was adopted by the European Parliament, calling upon the Kingdom of Morocco to “release all political prisoners'', including the release of Nasser Zefzafi, and to “end of the surveillance of journalists, including via NSO’s Pegasus spyware, and to implement legislation” which protects journalists. Further, increasing collaboration with Algeria (who, as above mentioned, is having its own political standoff with Morocco over Western Sahara) suggests that the short and medium-term ambitions of REPowerEU and Piano Mattei are at odds with the European Parliament’s adoption of Resolution 2023/2506. This is problematic for securing natural gas supplies to Iberia and the westernmost corners of the bloc, but potentially for regional stability in general. If the EU cannot strike the right balance between appeasing Algerian requests and reprimanding Morocco for its treatment of journalists, the prospect of tensions between the two North African states cooling off is not particularly positive. This indirectly impacts the operations of the Maghreb-Europe pipeline, and so on. Indeed, on January 23 2023 the Moroccan parliament “voted unanimously” to reconsider its ties with the European Parliament.

That said, Morocco-European relations are not exactly at an all time low – in terms of trade and commerce, at least. Trade between the EU and Morocco has increased significantly in the period between 2011 and 2021, and the North African state is the bloc’s 19th largest trading partner. Morocco is also among the top African trading partners for Greece, Italy, Portugal, and Spain. Therefore, there is still space for Morocco-Europe relations to improve within the broader scope of REPowerEU, the European Commission’s ‘Southern Neighbourhood’, and of course, Giorgia Meloni’s Piano Mattei.

Summary: Implications for the Political Economy of the Mediterranean

As the EU gravitates towards North Africa to ‘de-Russify’ its natural gas imports what diplomats and politicians should keep in mind two things: (i) the current tension between Algeria and Morocco, and (ii) diversifying gas imports is not (in the short-term) compatible with holding Morocco politically accountable for its mistreatment of journalists. It is an unlaudable conclusion, of course. But certain international relations theory – namely liberal institutionalism – would defend this claim as the theory emphasises understanding “the role that common goals play in the international system and the ability of international organisations to get states to cooperate,” as opposed to focussing strictly on power relations between states.

In the case of Mattei as a part of the EU’s ‘Southern Neighbourhood’ strategy, turning to the Mediterranean region means understanding the political tensions of North Africa in order to ensure the best outcomes for REPowerEU and Mattei, as well as avoiding antagonising the Kingdom of Morocco – even if the normative reasons for doing so are justified. Within the EU, the success of Piano Mattei in increasing Algerian gas supplies to Italy and the rest of the Transmed pipeline (which terminates in Slovenia) is intricately linked with REPowerEU’s short-term goals. Thus, as Arturo Varvelli elaborates in his commentary on the issue, Brussels and Rome ought to conduct themselves in a cooperative manner to ensure the success of Mattei and REPowerEU alike. If not, Meloni’s well-documented Euroscepticism could well be weaponised and used against Brussels, which would be a counterproductive outcome for Italy and the EU’s political legitimacy.

On these premises, then, the EU’s ‘Southern Neighbourhood’ strategy should also encompass the goals of REPowerEU to, first of all, secure alternative gas supplies, but also to cosy up to Rome and using the increased demand for non-Russian natural gas to quell Algiers-Rabat tensions. Equally, in pursuing the energy goals of Piano Mattei Giorgia Meloni should also consider using Italy’s diplomatic power to help find a solution that might reopen the Maghreb-Europe pipeline if she desires to obtain a reputation for closing deals and power brokering at the European level.

Outlook

Italian-North African gas exploration and trade deals may face significant challenges in the shape of Europe’s green energy transition.

Meloni will most likely be able to secure the ‘de-Russification’ of Italy’s natural gas supply, but whether this will hamper Rome’s green energy transition remains to be seen.

Forecasts would suggest that LNG futures prices will not fluctuate sufficiently to dampen the value of natural gas trade between Italy and its partners, Algeria and Libya, in North Africa.

Whether Meloni aims to cooperate with, or conspire against, the EU’s short and long-term energy policies remains to be seen.

At the present moment it is very unlikely that Algeria-Morocco relations will improve to the point of reopening gas flows to Iberia via the Maghreb-Europe pipeline. How the situation between both states remains a critical point for the energy policies of Italy and the EU at large.

Image Credits: ROSI Office Systems Inc.

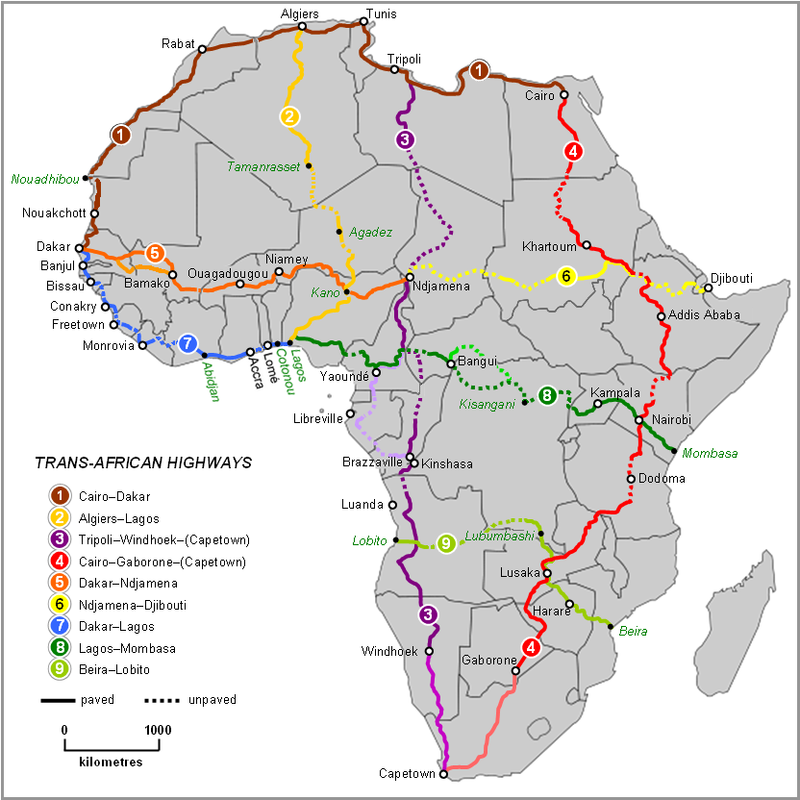

All roads lead to Africa: Opportunities and risks of the Trans African Highway network

In the build up to Nigeria’s next presidential elections due on 25 February 2023, the ruling All Progressives Congress (APC) party has suggested a suspension of spending limits in the budgetary process in its manifesto. According to presidential candidate Bola Tinubu, this would allow the government to “hire millions of unemployed Nigerians to modernise national infrastructure”, arguing that “a truly national highway system must be built to make road transportation faster, cheaper, and safer”. In the past, Minister for Public Works and Housing Babatunde Fashola has highlighted that these efforts transcend Nigeria’s borders, notably with the completion of the Trans–West African Coastal Highway (TAH 7): “We’re trying to deliver a better life for five countries and over 40 million people who use that corridor, almost on a daily basis. [...] The future is bright, this is an important investment for the people of Africa to achieve the objective of the Africa Union (AU) to create a trans-African highway.’’

Source: The Trans African Highway network, Wikimedia Commons, 2007.

The opportunities

This reinvigorated optimism for transnational transportation across the continent is embodied in the Trans African Highway (TAH) network, developed by the United Nations Economic Commission for Africa (UNECA), the African Development Bank (ADB), and the AU in conjunction with regional organisations. Financing is also supported by foreign development funds. The pursuit of such projects is vital to the development of African countries. In fact, the IMF estimates that around 40 per cent of the continent’s population lives in a landlocked country. Yet considering the high economic dependence of most African states on commodity exports and the low levels of intracontinental trade ー extra-African merchandise exports represented 86.6 per cent of total exports in goods from Africa in 2019 ー access to global shipping routes is vital. The completion of the TAH network coincides with the gradual setting up of the African Continental Free Trade Agreement (AfCFTA) which seeks to create a free trade zone encompassing all African Union states (bar Erythrea) and lift 30 million people out of extreme poverty by increasing intercontinental trade. UNECA highlights that the operationalisation of the AfCFTA will stimulate demand for land transportation and “double road freight from 201 to 403 million tonnes”.

The risks

Besides these potential opportunities, the gargantuan TAH network presents several economic, political, environmental, social and security risks. Economically speaking, the main risk source is the difficulty for developing countries to cover the high costs of maintenance. According to the World Bank, lack of maintenance can have aggravating socio-economic consequences: “poorly maintained roads constrain mobility, significantly raise vehicle operating costs, increase accident rates and their associated human and property costs, and aggravate isolation, poverty, poor health, and illiteracy in rural communities”. Furthermore, the South African National Road Agency estimates that “repair costs rise to six times maintenance costs after three years of neglect and to 18 times after five years of neglect”.

Politically speaking, an important risk source to the success of TAHs is the potential lack of cooperation of neighbouring states. Diplomatic leverage may be found in increasing bureaucratic processes at border crossings to cause congestion and delays ー although this risk may decrease in the long term as the AfCFTA is gradually implemented and imposes lighter border controls.

Environmentally and socially speaking, risk sources mostly emanate from rural areas. TAH projects may have to provide environmental mitigation and compensation for any ecological damage caused during construction phases, as well as go through long and complex acquisition processes due to tribal land ownership rules.

Finally, from a security perspective, the risk of land route disruptions and damage to infrastructure is extremely high in regions where conflict may arise, as is the case for the Ethiopian portion of TAH 4 which runs past the country’s war-torn northern regions.

Overall, the TAH network will undoubtedly help with African development through intracontinental trade. Yet, making this development sustainable for the decades to come will be a challenging feat Africans are already fully aware of: in the AfCFTA Secretariat's own words, “economic integration is not an event. It’s a process”.

Risks of the German gas plans

This comprehensive mini-report from the Global Commodities Watch identifies the risks involved with German preparations and plans to curtail Russian gas supplies.

Indonesia and the possibility of Russian oil

In an interview given to the Financial Times in September 2022 Indonesian President Joko Widodo, said his country needs to look at “all of the options” as it contemplates buying cheap Russian oil to deal with rising energy costs. This extraordinary measure would be the first time in six years that Indonesia imports any oil from Russia. As it concerns south-east Asia’s largest economy, the potential ramifications are significant.

Why is Indonesia’s government considering this?

Amidst the global inflationary environment, the Indonesian government recently cut its fuel subsidy by 30%, therefore increasing consumer fuel prices by a large margin. The higher price of oil since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine means the Indonesian government has spent ever greater amounts for the benefit of consumers. In order to control this swelling subsidy budget Widodo took the unpopular decision to decrease government support for fuel, leading to a series of demonstrations and protests.

With conflicting aims of limiting the increase in budget expenditure on the one hand whilst responding to public opinion for lower prices at the pump on the other hand, it is no small wonder the Indonesian government is considering buying cheaper oil. Jokowi says “there is a duty for [the] government to find various sources to meet the energy needs of the people”. Moscow offering discounted oil at 30% lower than the international market rate has therefore become an attractive solution.

Russia is left with no choice but to sell cheaper oil due to western sanctions, a situation which will worsen if and when the much-rumoured G7 price cap on oil is implemented. From December 5th onwards the EU and the UK will impose a price cap on Russian oil shipped by tankers or else prohibit their transport. This move is already giving India and other significant importers of Russian oil leverage in negotiating oil price discounts, an advantage Indonesia would benefit from.

Are there alternatives?

Yet alternative options do exist. In particular the sale of State-Owned Enterprises (SOEs) could fill the hole left in the Indonesian government’s energy budget. Partially privatising the government oil group Pertamina is being mulled, with the firm’s geothermal branch expecting its IPO before the end of the year. With its $606 billion SOE sector equivalent to half the country’s gross domestic product, the fiscal incentives for such actions are strong.

The government is also attempting to upgrade ageing refineries, in particular through a controversial partnership with Russian state energy company Rosneft. One of the projects, the Tubang Oil Refinery and Petrochemical Complex, is expected to cost $24 billion and will increase Indonesia’s crude refining capacity by 300,000 barrels a day. In the context of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, continued dealing with Russian SOEs poses its own complications in navigating western sanctions.

Risks and Outlook

The foremost risk with purchasing Russian oil comes from American warnings of sanctions for those involved in buying Russian oil using western services. With 80 per cent of global trade denominated in US Dollars, this could be difficult to avoid. The mere threat of such sanctions would affect the appetite of international investors, crucially regarding Indonesian government bonds. In the context of monetary tightening, this is a strong deterrent.

Yet the Indonesian government might follow the Indian model. Russia has recently become India’s largest supplier of oil, as India cashes in on the considerable price discounts offered. Yellen, the American treasury secretary, indicated that the US would allow purchases to continue as India negotiates even steeper discounts due to the western price cap. Monitoring the Indian case could prove fruitful as a bellwether for economic success and international reactions. However, the Indian government is less dependent on international investors' bond buying to fund its budget deficit meaning Indonesia’s risk exposure towards this is of greater importance

The Indonesian government will carefully study these options. Partially listing SOEs or increasing domestic refined supply may not make up the government’s budgetary hole without large-scale changes to the local economy. In the short term, Indonesia handing over its G20 presidency and shortly assuming the ASEAN one may factor into its decision.

In the long term, this temptation of Russian oil will remain. There are clear economic benefits to this by solving the conflicting aims of limiting budget expenditure while keeping consumer prices low. Furthermore, the United States’ tacit green light on buying Russian oil towards similarly developing countries minimises the chances of international reprimands.

This is reinforced by arguments often used against European countries to not buy Russian oil or gas holding little relevance in Indonesia. Notions of ‘supporting Putin’s war’ are of little geopolitical relevance to Indonesia if grain flows from Ukraine stay constant.

The likelihood that Indonesia will begin buying Russian oil is low. The scale of risks involved, particularly regarding sanctions, will dissuade the Indonesian government. The spate of interviews given in September from Indonesia's energy minister and President were likely moves to test the waters among investors and the international community. This decision is of course subject to rapid change given Indonesia’s unpredictable regulatory environment where policies can change on a dime.

The dilemma faced by Indonesia means that south-east Asia’s largest economy is firmly in the camp of countries calling for a rapid resolution to the Russia-Ukraine conflict.

Providing for the Peninsula

This collaborative research paper by London Politica’s Global Commodities Watch and Ukraine Watch sheds light on the critical infrastructure for the supply of Russian water, fuel and military equipment through and for Crimea and investigates how these may be affected by pressure from Ukrainian forces in the months to come.

China’s push for hydrogen energy: The power of ambition for green infrastructure

In March 2022, China announced its target to produce approximately 200,000 tonnes per year of green hydrogen and at least 50,000 hydrogen-fuelled vehicles by 2025 to supplement its target of reaching net-zero carbon emissions by 2060. This comes after a huge push for hydrogen use during the 2022 Winter Olympics in Beijing. With China being the world’s largest producer of hydrogen at 33 million tonnes annually—80% being grey or blue hydrogen, widespread usage of green hydrogen is anticipated for China’s energy infrastructure.

In understanding hydrogen, there are three main forms: grey, blue, and green. Grey hydrogen is generated using fossil fuels and other high carbon-emitting sources and blue hydrogen is produced using low carbon-emitting sources such as steam methane reformation with Carbon Capture, Usage and Storage (CCUS) or other fossil fuels with CCUS. On the other hand, green hydrogen is made through the electrolysis of renewable energy sources and emits no carbon emissions.

The success of China’s move towards green hydrogen will depend on whether it can geographically connect its renewable-rich regions in the western provinces to the high hydrogen demand areas on the coast in China’s eastern provinces, as well as efficiently and cost-effectively store hydrogen during periods of high production yet low demand for green hydrogen energy. For example, while energy supply of hydrogen produced from solar energy sources usually outweighs demand during the summer months, energy demand rises during winter months due to higher electricity needs—such as for heating—and lower solar energy generation on account of shorter days during the winter. For this reason, green hydrogen energy storage is crucial to meet mismatched demand and supply periods.

In terms of transportation, hydrogen can be transported in a variety of ways depending on the transportation distance. For shorter distances, retrofitted pipelines for high-pressure gases or natural gas blending are the best options. Currently, China has two pure hydrogen pipelines in place—although both are under 500 kilometres—and one hydrogen-natural gas blending pilot project. For longer distances, hydrogen could be shipped in the form of ammonia, gas tanks, liquefied, or through retrofitted subsea transmission pipelines. However, converting hydrogen to ammonia or cryogenic liquid is still extremely expensive and nascent in terms of technology, especially as liquid hydrogen technology is only used in China’s aerospace and defence sectors. This also poses a problem for hydrogen storage in the form of liquid.

Another option is underground storage within depleted oil and gas reservoirs, salt caverns, or aquifers. However, China’s natural storage options are limited; thus, there is large scale investment into developing underground gas storage across China. Hydrogen can also be stored through gaseous storage and tube trailer technologies; however, steel containers used in China for hydrogen storage have a lower pressure capacity than that used in Europe, North America, Japan, and South Korea. Hydrogen regulations must therefore be amended to improve China’s competitive hydrogen storage ability.

While challenges for transportation and storage persist, ambition for green hydrogen energy usage across China is growing. The country now has more than 250 hydrogen refuelling stations, making it the country with the highest number of hydrogen refuelling stations globally. Moreover, investments are being poured into green hydrogen infrastructure and technology solutions in China. There is no doubt that in due time, China will be a key player in the global hydrogen industry.

Pipeline sabotage? Nord Stream and the politicisation of critical infrastructure

On September 26 and 27, gas leaks and explosions were reported on the Nord stream 1 and 2 pipelines. These occurred in Baltic Sea international waters, near the Danish island of Bornholm. Although neither of the pipelines was active at the moment, the amount of gas leakage was still significant. The timing, significance, and location of the leaks has led some to speculate that it was sabotage and that Russia deliberately attacked the pipelines.

So far, however, Western governments and officials have refrained from pointing fingers directly to Russia. As NATO secretary general Jens Stoltenberg argued: “This is something that is extremely important to get all the facts on the table, and therefore this is something we’ll look closely into in the coming hours and days”. It has however highlighted the importance of critical infrastructure and its role in the current stand-off between the West and Russia.

So what consequences did the leakage and supposed ‘sabotage’ have?

Economic consequences

The damage to Nord Stream coincided with news that new arbitrations over payments might lead to Russian sanctions against Naftogaz, Ukraine’s largest oil and gas companies. Consequently, benchmark futures of natural gas jumped 22%, the highest increase in over three weeks. Markets seem to have taken into consideration that now that pipelines have been damaged, the EU can’t request for them to be opened in case of an emergency. Nevertheless, with storage sites nearly at full capacity, heightened LNG imports, and mild weather forecasts for October, markets remained relatively calm.

Environmental

The environmental impact has been significant. Gazprom estimated that 0.8 bcm was released at the leaks. That number is almost equal to 1% of annual UK natural gas consumption, or 3% of its annual emissions. Were both pipelines actually active, the impact could have been much worse.

Political

After Danish and Swedish authorities launched investigations, suspicions of sabotage strengthened. In a statement by the Swedish security police, they said there were “detonations”. And in a joint letter to the UNSC, they stated that leaks were probably caused by an “explosive load of several hundred kilos”. President Biden argued the leaks were a deliberate act of sabotage as well. Meanwhile, Russian president Putin claimed the US and its allies were behind the attack.

The main logic behind a potential sabotage from the Russian side would be intimidation. Both in the Baltic Sea and the Atlantic, lots of critical infrastructure, such as pipelines or IT-cables, lie on the seabed. The attack on Nord Stream therefore would be a showcase for what Russia could do to other critical infrastructure. Ultimately, however, it would also mean that Russia has lost its element of leverage with gas.

As a consequence, EU energy ministers discussed the issue and European countries stepped up military patrols. In the North Sea, Germany, the UK, and France helped Norway in a show of force to increase security and patrol near energy sites. This was also a consequence of several unidentified drones being spotted near the sites. In the Mediterranean, Italy increased patrols near its pipelines which connect North Africa to Europe.

Risks

If this event turns out to be Russian sabotage, it adds a dimension to the conflict between the West and Russia. Although that conflict consisted of economic warfare and aspects of hybrid-warfare, physical attacks (on critical infrastructure) were absent. It begs the question whether we have entered a new phase of the war.

The risk, however, of physical attacks on other critical infrastructure remains limited. It is important to highlight that no gas flows were disrupted, because of Nord Stream’s inactivity. Combined with the ambiguity that was left about the perpetrator of the attacks, damage could be done without any consequences. This grey-zone aggression has been part of Russia’s playbook for years. Nevertheless, Russia knows the significance of physical attacks on other active pipelines would be far greater, and are more likely to trigger an article 4 or 5 response from NATO, even where proof is hard to ascertain. This limits the risk of physical attacks on other critical infrastructure.

The risks of 1) cyber attacks on critical infrastructure and 2) physical attacks on pipelines running through Ukraine, on the other hand, are greater, because it is more likely that Russia can maintain ambiguity there. It demonstrates the vulnerability of critical infrastructure and the difficulty of responding to coordinated attacks.