The 2020s Commodities Boom: How Long Before the Outlook Dives?

The link between commodities boom during recession and inflation is well-established. During a recession, central banks often lower interest rates to stimulate economic activity, which can lead to inflationary pressures. Inflation can also be driven by increased demand for commodities as economies recover. This was evident during the global financial crisis of 2008-2009, where a sharp increase in commodity prices occurred during the recovery phase.

Similarly, the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 led to a sharp recession, followed by a commodity boom in 2021 due to a combination of factors, including supply chain disruptions and increased demand as economies reopened. The result was a surge in commodity prices, including oil, copper, and agricultural commodities that had continued well into 2023. It is important to highlight these dynamics between economic performance, and commodity rallies, to better outline market performance, and make better long term trading decisions. The link between commodity prices and inflation is made visually available by the St. Louis Federal Reserve.

To project when the outlook in the commodity markets can settle down a time-series analysis must be conducted using historical data to identify trends and patterns in commodity prices, such as the ones above. The analysis must also include macroeconomic variables such as interest rates, inflation, and GDP growth to identify the drivers of commodity prices. However, it is important to note that commodity prices are highly volatile and subject to various unpredictable factors such as natural disasters, political instability, and global events. Yet, based on current trends and projections, it is likely that the commodity boom will eventually settle down as global supply chains stabilise and interest rates cool down. However, the timing and extent of this will depend on a range of factors and will require ongoing monitoring and analysis.

The most likely estimate would be, not before FY2024. Given the reaction of markets to the increase in interest rates, multiple cases of bankruns, the subsequent banking crises, and ongoing Russian invasion of Ukraine, volatility is here to stay for the short-run. However, the CPI (Consumer Price Index) has been showing signs of improvement, with inflation in North America, and the Eurozone, almost at the cusp of weathering down. This follows a decline in energy prices, and can be credited to deflationary fiscal policies aimed at slowing monetary velocity. Given the response of the Federal Reserve, the fallout of the bank failures has been prevented from adding fuel to the fire, and efforts from both banks, and the government, to reassure depositors of confidence in the institutions that govern them, have allowed for the stabilisation of outlook for the short run. To conclude, investors can expect the commodities rallies to continue through 23’, although as economic and geopolitical forces begin to stabilise, the inflated boom can be seen as a short term bubble, waiting to burst as growth returns.

Extension of the Ukraine Black Sea Grain Initiative: Impact on Global Food Supply Chains

Since the beginning of the Russian invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, Ukrainian grain exports have been severely disrupted. Russian military vessels were carrying out a blockade of Ukrainian ports in the Black Sea for four months. On July 22 2022, an agreement was signed between Russia and Ukraine, mediated by the United Nations and Turkey, to maintain a safe maritime humanitarian corridor in the Black Sea, also known as the Black Sea Grain Initiative. Since then, about 900 ships carrying grain and other food items have departed from the Ukrainian ports of Chornomorsk, Odessa, and Yuzhny/Pivdennyi. When the time came of the end of the original deal, Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky and the UN Secretary-General António Guterres both called for an extension of the deal, thereby enabling Russian and Ukrainian wheat and fertilisers to be exported through the Black Sea.

Initially, Ukraine and Russia had signed the deal for an initial 120 days last July, thereby averting a possible global food crisis. A subsequent November extension to the Black Sea Grain Initiative for an additional four months was due to expire on March 18, 2021, unless it was extended. While the UN and Ukrainian government backed the extension, the Kremlin was unhappy with specific provisions of the deal, thereby renewing fears of grain traders regarding potential risks to supplies and the potential increase in global grain prices. On March 18, 2023, the Ukrainian Deputy Prime Minister elucidated that the deal had been extended for 120 days. However, Moscow reckoned that it had agreed to a 60-day extension only, and a Russian Foreign Ministry letter to the UN said that the country was only willing to extend beyond the stated 60 days in the face of ‘tangible progress' towards unblocking flows of Russian food and fertilisers to world markets. The Turkish President, Recep Tayyip Erdogan, confirmed the rollover of the deal but did not comment on the exact duration of the extension.

As of March 2023, over 23 million tonnes of grain and other foodstuffs have been exported via the Black Sea Grain Initiative. Approximately 49 per-cent of the cargo constituted maize, the grain which was most affected by blockages in Ukrainian granaries at the start of the war, i.e. (75% of the 20 million tonnes of grain stored). It had to be displaced quickly to make room for the summer harvest. Wheat constituted 28 per-cent, sunflower products 11 per-cent and others 12 per-cent. Over 65 per-cent of the wheat exported through the Black Sea Grain Initiative went to developing countries. Maize was shipped to both developing and developed countries almost equally. 63 per-cent of wheat was exported to developing countries and 35 per-cent to developed countries. So far, approximately 456,000 tonnes of wheat departed Ukrainian ports to reach Ethiopia, Yemen, Djibouti, Somalia, and Afghanistan. The EU is a major global producer and exporter of wheat. In 2022, according to estimates, the EU exported approximately 36 million tonnes of soft wheat to Algeria, Morocco, Egypt, Pakistan, Nigeria and others. The Russian invasion of Ukraine caused a significant surge in food prices in global markets; the prices of particular grains rose steeply. The impact on price and the types of grain which have been exported through the Black Sea Grain Initiative is made available by an infographic published by the the Council of the European Union.

The extension of the deal is a significant success. Grain traders were concerned about the effects on global food prices and what it would imply for Ukraine’s summer wheat harvest had it not been extended. Shipping industry Representatives also appreciated the smooth functioning of the grain corridor. They feared that any end to the agreement would lead to the instantaneous stopping of vessels travelling to the Black Sea. Guy Platten, the Secretary General of the International Chamber of Shipping, elucidated that while the corridor had been a great success, any failure in a roll-over would have caused significant concern for shipping companies, who would not want to endanger their vessels and crew and would find it difficult to obtain insurance.

Market experts had also shared the fears that at a time when developing countries like Pakistan have been impacted by their own fair share of climate catastrophes like floods, leading to a massive destruction of crops, surge in energy prices as well as shocks to global supply chains due to the Russian invasion of Ukraine and high levels of inflation, a shock to grain exports, and subsequent rises in food prices would lead to a significant food crisis. Even in the developed world, for instance, in the EU, amid the cost of the living crisis and supply side shocks, higher global food prices would make essential edible items too expensive for people. Thus, the renewal of the agreement has been deemed a significant achievement.

Before the war, exports from Russia and Ukraine constituted about 30 per-cent of the global food trade. Between 5m to 6m tonnes of grain were exported each month from Ukraine’s seaports, according to the International Grains Council (IGC). The volume carried by ships via the grain corridor gained momentum towards the end of 2022, as per the Executive Director of the IGC, i.e. a very impressive level of export. In November and December 2022, Ukraine was close to approximately the same level as before the war in terms of exports by sea plus inland. While exports had slightly reduced in January and February 2023 due to poor weather, Ukrainian power outages affecting port facilities and delays in grain inspection delays, however, the overall success of the shipments of essential wheat, maize, oil seeds and barley from the Black Sea since August 2022 to countries reliant on grain imports had led to a fall of 30 per-cent in global wheat prices since its June peak. Thus, the 60-day extension of the agreement was widely praised and calmed fears of potential after effects on a wide range of industries and food prices.

Despite Kremlin’s concerns, it is likely that the UN and Turkey would mediate to have the agreement extended beyond the 60-day period and that Russia would agree to that because both Ukraine and Russia export considerable amounts of world’s grain and fertiliser, together supplying approximately 28 per-cent of global traded wheat and 75 per-cent of sunflower oil during peacetime. Moreover, as of 18 March, the UN Secretary General was adamant to seek ways to unblock Russian food and fertiliser shipments, which were blocked by sanctions targeting Russian oligarchs and the state agricultural bank. The Kremlin blames these sanctions for the ongoing food insecurity in the Global South. In the coming days, we may see easing of some sanctions that target Russian food exports, while overall sanctions may persist.

How unrest in the DRC is affecting commodity supply chains

In late February, M23 rebels seized the town of Rubaya in the North Kivu province of the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC). The town is a major coltan mining centre and its seizure is just the latest in a series of attacks by rebel groups on mining operations in the DRC, which has some of the world’s largest reserves of minerals including cobalt, copper, and coltan. In the same month, M23 captured the key towns of Mushaki and Mweso, bringing them ever closer to the regional capital Goma.

The M23 rebellion first emerged in 2012 and was initially defeated by Congolese and United Nations (UN) forces in 2013 but the group has continued to carry out sporadic attacks in the region since then. The latest seizure of Rubaya highlights the continued instability in the area and the challenges faced by the DRC government in maintaining control over its mineral wealth. The coltan supply coming from North Kivu will likely decrease because of this, which will lead to prices increasing in an already expensive market. Coltan contains niobium and tantalum, critical components in many electronic devices, as well as being important in the aerospace, healthcare, and energy industry. The international community may have to shift their attention away from the ongoing crisis in Ukraine if the situation continues to spiral.

The mining of these minerals often involves dangerous and exploitative working conditions, and profits from the industry have been linked to armed groups in the region. The situation is further complicated by the involvement of neighbouring countries such as Rwanda. Despite the DRC government alleging that M23 are receiving support in arms and men from Rwanda, this accusation was not levelled against Rwanda at the Community of Central African States nor the East African Community’s (EAC) at recent gatherings. With the DRC already struggling to contain the issue from spreading to other provinces, it is unsurprising that they would not want to throw more oil onto the fire and risk inciting harsher retaliation from Rwanda.

While it is unclear yet what this means for the future of the DRC, the loss of Goma would represent a major challenge to the authority of the government. Other dormant rebel groups may try their luck against a weakened central government. In addition to this, the DRC will likely pay close attention to the actions of Rwanda if M23 marches on Goma. With Lake Kivu preventing any attack from the south on Goma, the rebels will have to attack in two prongs from the north and west of the city. If reports emerge of fighters attacking Goma from its eastern border with Rwanda, Rwanda’s claims to not be supporting the group will become even more dubious.

The scale of the humanitarian crisis caused by such an attack, whether with help from Rwanda or not, would lead to a catastrophic loss of life. In the case of a capture of the city, thousands of people would be displaced or trapped within the zone of conflict with few options of escape. Both the UN and EAC have recognised the scale of this upcoming problem, with the UN calling for more than half a billion dollars in aid and the EAC calling for all rebel groups to withdraw from Eastern Congo.

With war in eastern Europe still ongoing, EU nations and the US are focused on Ukraine. This means material assistance to the DRC will most likely come from the EAC. In the best case scenario, this may not even be needed as M23 have previously caved to international diplomatic pressure and retreated from recent gains in December and January. But it is doubtful that they will take the same actions again given how close to a major objective they are and after already retreating from it.

As mentioned, the DRC is a vital source of other commodities whose supply and price would be adversely affected by the breakdown of the central DRC government. Cobalt and Copper, for example, have a wide range of applications, such as electronics and construction. While companies in these industries look for alternative sources for these minerals, they would be forced to pay higher prices thereby increasing prices for consumers as well. With inflation reaching record highs across parts of the world coupled with the reliance many industries have on technology, rising commodity prices could lead to decreased spending from consumers.

Oil sanction circumvention - the need to shift the focus on sanction implementation

In June 2022, the Geneva-based company Paramount Energy & Commodities SA stopped its activities, and opened an identical company in Dubai under the name of Paramount Energy & Commodities DMCC. Until the relocation, Paramount SA was a small business specialising in trading Russian crude. In the two months following the beginning of the Ukraine War in February 2023, the Swiss company purchased 11.7 million barrels of oil, making it the fourth global largest buyer of Russian crude following only the industry giants Litasco, Trafigura, and Vitol. Its founder, Niels Troost, a Dutch citizen, used to be a tennis partner of Gennady Timoshenko, founder of the multinational commodity trading company Gunvor and close associate of Vladimir Putin. Following the price cap of $60 a barrel introduced in December 2022 by the G7 on Russian crude oil, the newly established Paramount Energy & Commodities DMCC kept trading the same oil it used to trade when it was based in Geneva, at a price above $70 a barrel, thus higher than the price cap. However, nowadays it is using United Arab Emirates lenders and ships registered to companies based in China, India and the Marshall Islands, countries that have not imposed sanctions on Russia. This allows it to bypass the current G7+ sanctions, which prohibit companies or individuals from the US, EU, UK and Switzerland from trading, shipping and insuring Russian oil sold at a price above the price cap. The Russian producers that sell oil to Paramount DMCC are Rosneft, Gazpromneft and Surgutneftegas, all sanctioned by G7 and EU countries. The main buyers are located in China, which after the beginning of the war has boosted its imports of Russian oil, counting on its increased bargaining position vis-à-vis Moscow to obtain lower-than-market prices. For this reason, officials from the EU, US and UK have visited the UAE to press Emirati authorities to curb sanctions’ circumvention.

This is not just related to oil. Another cause of concern for the G7 is the so-called “re-export” of high-tech goods, where electronic items are first exported from Western countries to the UAE or Central Asian states, and then, as a second step, from those countries to Russia. This is why last year there was a more than seven-fold increase in the UAE’s export of electronic parts such as microchips and drones from the UAE to Russia, while exports from the EU and the US to Armenia and Kyrgyzstan surged by 80% from May to June 2022.

The activity of companies such as Paramount DMCC risks jeopardising the objective of G7’s price cap of slashing the Kremlin’s oil revenue and reducing global energy prices, but without completely blocking Russian oil flows to Europe. These companies contribute to selling Russian crude at prices well above the price cap and they are also diverting oil flows away from European markets. The CEO of the maritime data company Windward, Ami Daniel, reported witnessing numerous cases in which individuals from countries including the United Arab Emirates, India, China, Pakistan, Indonesia, and Malaysia purchased ships to establish a non-Western trade structure with Russia. At the same time, Russia is using Iran’s “ghost fleet” to bypass G7’s price cap. This consists of vessels that disguise their ownership and their movements by turning off satellite trackers or transmitting fake coordinates. These vessels also transfer Russian oil between ships in international waters, all with the aim of concealing the origin of the crude and selling Russian crude at a higher price than the price cap.

As a result, the IMF forecasted Russian oil exports to remain robust, shifting towards nations that have not enforced the price cap. Overall, despite the sanctions, the Russian economy is expected to grow by 0.3% in 2023. Implementing sanctions effectively is a cat-and-mouse game. G7 and EU countries will need to shift their focus on enforcement to ensure that sanctions achieve their goal of denying the Kremlin’s ability to finance the war.

Financial turmoil’s fallout for commodity markets

The fallout from last week’s SVB crisis sent worrying signals across global financial markets, and caught crude oil and other commodities in the downdraft. Oil prices tumbled on fears that the crisis would spread, feed into the physical economy, and cause a potential economic slowdown. The events, however, also saw even the most ardent bulls (Goldman Sachs) change their oil price outlooks as hedge funds began buying oil put options.

WTI crude sank below $65 per barrel and Brent was down about 10 per-cent on a weekly basis. The price decline was accentuated by forced selling of speculators who had built up bets on higher prices in recent weeks - assuming that Chinese oil demand would recover and Russian oil exports would wane in response to strengthening sanctions. Russian oil flows, however, proved more resilient than previously thought. Furthermore, swelling oil stocks, signaling weak demand because of the mild winter, could not be ignored by the markets.

Gold (and other precious metals), on the other hand, saw increased demand as investors increasingly sought for a safe haven for their investments. As a result its price rose above $2000 an ounce, for the first time in a year.

The irony of last week’s events is that the Saudi government is now paying the price, after the Saudi National Bank ruled out putting up more cash for Credit Suisse. Not only did Credit Suisse shares plunge, resulting in a UBS takeover and a $1 billion Saudi loss, but also did it trigger a macro meltdown that carried Brent and WTI with it.

Outlook

The ultimate impact on commodity markets will depend on the degree of transnational contagion following the collapse of SVB and UBS' acquisition of Credit Suisse. Spreading of the crisis will likely affect the physical economy and halt demand for oil, resulting in more price declines. Containment, on the other hand, assures traders that the physical economy will be relatively unaffected, allowing prices to gain steadily.

But there are more factors at play. The financial turmoil affected the Fed’s monetary tightening, the effects of which will trickle down into commodity markets, specifically crude oil. Wall Street earlier used the SVB crisis to demand that the Fed does limited or no more monetary tightening, until it is certain that the economy is sound and it won’t accelerate towards recession. Fed officials, on the other hand, argued that they have the tools to handle the SVB contagion and it is more important that the fight against inflation continues with more rate hikes. A hawkish stance on interest rates will raise consumer and manufacturing costs, which will reduce demand for oil and likely result in a price drop.

Inflation, however, showed signs of slowing down with the CPI rising 6 per-cent in February, down from 6.4 per-cent in January. As a result, the Fed increased its rate by 25 basis points, instead of the more hawkish 50 basis points. The Fed, however, did not rule out increasing its rate in the future. In line with the Fed, the BoE also increased its rate by 25 basis points, after its annual inflation rate jumped to 10.4%.

Price declines have also raised the prospect of the U.S. government buying oil to replenish its strategic petroleum reserve (SPR) - a move that could stabilize demand. The White House set a price range of $67-72 per barrel where it would buy back crude oil, and prices are currently below the bottom range. The Biden administration, however, has not committed yet and stated to view the situation day-to-day.

On the OPEC(+) side, Saudi and Russian officials met to discuss the stability of global oil markets. Price declines have raised the prospect of intervention from OPEC+, and news of the Ruso-Saudi meet-up was enough to see oil prices gain some currency and raise beliefs of some kind of intervention.

In the longer-term, price declines could be upset by increasing Chinese demand. On Wednesday, the IEA said that China is expected to drive a two-million-barrel rise in the world’s daily oil demand this year, pushing it to a record 102 million. Expecations in the oil market, however, vary, because the Chinese government set its growth rate target at a modest 5%, signaling a changing economic environment, which could impact oil demand..

Stronger fundamentals ultimately will decide whether oil prices go up to down. The expectation now is that fundamentals will reassert over time, meaning that the banking turmoil impacted commodity markets only in the short-term. Ultimately, however, this rests on the degree of contagion in the financial system. Ongoing developments in the financial system, Fed interest rates, SPR buybacks, OPEC intervention, and Chinese demand, therefore are key events to watch for in the future.

India’s Lithium Rush: Supply Chains, Clean Energy, and Countering China

The discovery of vast lithium deposits in the Indian territory of Jammu and Kashmir is being hailed as a win for the country’s clean energy transition. With the government already promoting domestic EV manufacturing, this could prove to be one of the missing pieces for the puzzle of an Indian EV supply chain.

Background

With rising demand for portable electronics and a push for a low-carbon future, lithium has become one of the most important minerals. Given its application in lithium-ion batteries, it is vital for powering everything from electric vehicles and portable electronics to stationary energy storage systems.

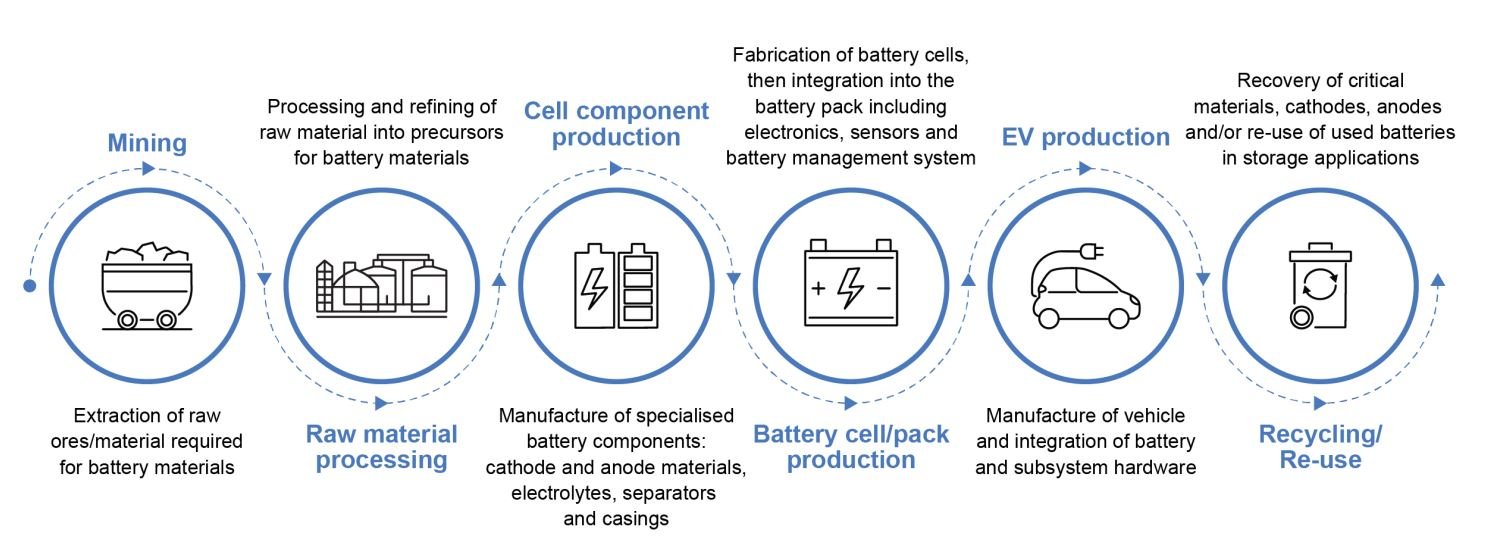

In particular, Lithium-ion battery demand from EVs is set to rise sharply, from the current 269 gigawatt-hours in 2021 to 2.6 terawatt-hours (TWh) per year by 2030 and 4.5 TWh by 2035. According to BloombergNEF’s (BNEF) Economic Transition Scenario (ETS) – which assumes no additional policy measures – global sales of zero-emission cars will rise from 4% of the global market in 2020 to 70% by 2040. Consequently, the global supply chain for lithium has become increasingly important.

EV battery supply chain. Image credit: International Energy Agency

The lithium supply chain is complex, involving multiple stages and players, and is subject to geopolitical and economic factors. Most of the world’s lithium deposits are in the ‘Lithium Triangle’ of the world in South America – Chile, Argentina, and Bolivia. Of these three, however, only Chile Ranks amongst the list of the world’s top lithium producers, headed by Australia. Apart from production, China dominates both the refining and battery manufacturing in the EV battery value chain.

Source: Statista

India: The New Potential Partner of the World

Given the global geopolitical environment, singular dependence on China for a vital resource such as lithium has far-reaching strategic implications. Naturally, democratic nations across the world are prioritizing the reconfiguration of their supply chains for critical manufacturing inputs. Combining its demographic dividend, educated and sufficient workforce, and entrepreneurial spirit– India is rising as a potential and reliable partner. The European Union’s ‘China + 1’ strategy, the EU-India Trade and Technology council, the United States’ recent Initiative for Critical and Emerging Technologies (iCET), and Australia’s Economic Cooperation Trade Agreement with India – testify to the merit that the liberal-democratic world order sees in a partnership with India.

In the given friend-shoring environment that India enjoys, the recent discovery of 5.9 million tons of lithium in the country is monumental. India’s automobile sector itself is transforming. According to NITI Aayog, by 2030, 80% of two and three-wheelers, 40% of buses, and 30 to 70% of cars in India will be EVs. The newly found lithium can help the nation meet rising demand, both domestically and globally. India’s government has already been pushing for electric mobility and domestic EV manufacturing. The 2023-24 Union Budget, allocated INR 35,000 crore for crucial capital investments aimed at achieving energy transition, including efforts for electrification of at least 30% of the country's vehicle fleet by 2030 and net-zero targets by 2070. For EV manufacturers, the government has launched initiatives such as the Faster Adoption of Manufacturing of Electric Vehicles Scheme – II (FAME – II), allocating approximately $631 million towards subsidizing and promoting the adoption of clean energy vehicles.

Indian Lithium deposits: Risks and Challenges

The recent discovery in the Reasi district of the Union territory of Jammu and Kashmir solves one of the major challenges to a localized li-ion battery supply chain in the country– access to lithium deposits. However, there are more challenges ahead.

Firstly, the Reasi district is just 100 kilometres from the Rajouri district, a geopolitically sensitive area. Although today these areas are well-connected to India with proper infrastructure, including airports and highways, the Line of Control between India and Pakistan is less than 100 kilometres from Rajouri and around 200 kilometres from Reasi. The region’s proximity to Azad Jammu and Kashmir also makes it vulnerable to militant activities. Greater infrastructural development in the region, including a robust logistics network will have to be developed to ensure an uninterrupted indigenous supply chain (given that other stages of the supply chain are also established domestically).

Secondly, although the Geological Survey of India (GSI) has the capacity to discover and locate lithium deposits, the remainder of the value chain to produce commercial-grade lithium indigenously is not in place. Similar to Australia, Canada, and China, the identified lithium reserves in India are in hard rock formations. In order to extract the resource, mining capabilities will first have to be established in the region. It is still unclear whether these reserves will be managed by state authorities or undertaken by the central government, given the strategic importance of the resource. Furthermore, whether the mines be auctioned, like India’scoal mines, or entrusted to a public sector enterprise, is not yet known.

Timely and major investment in developing refining, processing, and purification technologies will be required. India will have to build a large-scale capacity for transforming extracted material into high-purity lithium in order to take full advantage of this discovery. While the opportunity is considerable, so are the costs. India’s government will need to devise a clear strategy that effectively helps both the country’s energy transition and domestic manufacturing ambitions.

Image credit: Nitin Kirloskar via Flickr

Dire Straits: China’s energy import insecurities and the ‘Malacca dilemma’

In 2003, then President of China Hu Jintao named China’s energy imports passing through south-east Asia as the “Malacca dilemma”. The dilemma refers specifically to the Strait of Malacca, 1,100 kilometres in length and at its narrowest point only 2.8 kilometres wide, which has been a persistent source of vulnerability for the Chinese economy. Located between Malaysia, Indonesia, and Singapore, this strait is a transit point for around 40 per cent of global maritime trade and, perhaps more consequentially, 80 per cent of China’s energy imports. As the main shipping channel between the Indian and Pacific oceans, this connects the largest oil and gas producers in the Middle East with their largest markets in east Asia and is a strategic chokepoint for the 16 million barrels of oil that pass through daily. The Strait of Malacca is therefore critical to China’s energy production and wider economy, yet is not under Chinese control. What makes this shipping route a particular insecurity for Beijing, and what is being done to mitigate against it?

Major risks

China’s reliance on imported hydrocarbons for energy production, mostly on oil, is at the root of this insecurity. To fuel continued industrial development, energy consumption will increase rapidly alongside a widening gap between domestic energy supply and demand- in 2017, China surpassed the United States as the world’s largest importer of crude oil. Around 70 per cent of the country’s oil requirements come from imports, with analysts estimating this dependency will increase to 80 per cent by 2030. China is thus vulnerable to external shocks, whether in the price of oil or in its supply. That the vast majority of this oil supply passes through the Strait of Malacca chokepoint adds to Chinese evaluations of a precarious overreliance.

Geographically, the strait’s narrow span is a particular threat. With strong regional security actors in Malaysia, Indonesia, and Singapore added to the projection capabilities of India or the US, the risk for China is that a country or group of countries could easily control the strait and its flows. The Indian navy is notably building its presence in the area with its base in the Great Nicobar Islands, largely in response to China’s maritime Belt and Road Initiative projects. Additionally, Singapore is a major US ally that frequently participates in joint naval drills and is located at the eastern mouth of the strait. There is a strong possibility that states other than China can control the strait and greatly hurt the Chinese economy if desired, due to its high imported oil dependence.

South-east Asia is also particularly prone to piracy. A total of 134 separate piracy incidents were identified in the Strait of Malacca in 2015, with oil tankers among those targeted. Malaysia, Indonesia, and Singapore have been able to curb this issue to a large extent, but ships will still face insurance premiums on piracy when passing through the strait. Whilst this remains a background issue when compared to China’s oil import dependency and the strait’s potential for blockades, there is an ever-present risk of losing assets to piracy.

If access to the Strait of Malacca was hindered by piracy or indeed by other states, the economic impacts would be colossal. Beyond short-to-medium-term adjustments in the Chinese economy, a shifting of supply to using longer routes through the alternative Lombok or Makassar straits would add an estimated $84 to $250 billion per year to shipping costs. Rerouting one of the most important shipping lanes would gridlock global shipping capacity and, highly likely, increase energy costs worldwide. The economic upheaval as a result of the 2021 Suez canal blockage illustrates this strongly, yet would pale in comparison to a blockage of the Strait of Malacca.

Forecasting scenarios

The above risk factors thus place China in a precarious position regarding the strait. Whilst states blockading an open seas shipping lane may seem fanciful at the moment, China’s ‘Malacca dilemma’ could become a reality very quickly, especially when considering a change in Taiwan’s status quo. Taiwan is geographically far from the strait but if tensions were to increase over its status, the Strait of Malacca could see a greater security presence in response. Tangibly the US security guarantee to Taiwan means in the event that Taiwan was invaded, or even blockaded as a precursor to invasion, the US could impose an analogous blockade in the Strait of Malacca. China’s vulnerability regarding this strait leaves it open to some proportional responses should it grow more assertive in regional security. The prospect of greater American or US-allied control over the Strait of Malacca is likely in a hypothetical wartime scenario.

On allies, the wider Indo-Pacific region is seeing greater security cooperation as a reaction to increasing Chinese presence. The recent AUKUS military alliance between Australia, the United Kingdom, and the US entrenches American security interests in the region and provides new capabilities for Australia. The Quad grouping between Australia, the US, India, and Japan does not yet have a concrete security element, but could rapidly become an important player in the Strait of Malacca if the threat perception from China changes. Overall the expectation is for these budding Indo-Pacific alliances to gain a stronger strategic focus on the Strait of Malacca and the oil passing through it, critical to China’s economy.

Supply chain mitigation

Beijing is attempting to decrease its vulnerability to the risks and scenarios identified above. Above all other strategies, the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC), a part of the Belt and Road Initiative, seeks to mitigate against the ‘Malacca dilemma’. CPEC is an opportunity for China to have an access point to the Indian Ocean through the construction of a new pipeline from western China to the new port of Gwadar in Pakistan. The overall infrastructure investment is valued at $62 billion, with the Gwadar port expected to be fully operational between 2025 to 2030. However, CPEC faces various problems. The difficult topography of the Himalayas means high transit costs for the pipeline, far beyond that of shipping through the Strait of Malacca. Passing through unstable regions adds to the logistical difficulties, with terrorist activity reported in regions the CPEC passes.

The recent China-Myanmar Economic Corridor (CMEC) can be evaluated in a similar manner. The Kyaukpyu Port developed by the Chinese government will send 420,000 barrels of oil a day via the Myanmar-Yunnan pipeline. This nevertheless pales in comparison to the 6.5 million China-bound barrels per day that pass through the Strait of Malacca. In addition, Myanmar’s military coup and the future possibility of high-intensity civil war puts CMEC in peril. Chinese investments have been damaged, with serious doubts about CMEC’s security evidenced by fighting along the infrastructure route.

It is therefore clear that while China is developing alternatives to the Strait of Malacca, these remain woefully inadequate and there is no single replacement for the importance of the strait. Because of their respective political instabilities, ensuring that CPEC and CMEC are successful can only be one part of a solution. Diversifying away from crude oil shipping is another, and land-based pipelines will continue to be developed with central Asian countries and Russia. Of course, avoiding foreign control of the Strait of Malacca is preferable, but China is beginning to hedge on other sources for its imported oil.

In summary, it seems likely that China will continue to heavily depend on the Strait of Malacca to meet its energy needs. The strait remains a vulnerability, especially in the regional context of increasing security competition with other states. Various mitigating measures are being taken to lessen the impact of any change to this strategic chokepoint, but no cure-all solution exists. The geographic production centres and transit lanes for oil are one of the most significant issues for China and its economy and are sure to command the attention of all parties involved.

Image credit: dronepicr via Flickr

Lithium in Iran: Iranian Gold is Black & White

Iran's Ministry of Industry, Mine, and Trade has declared that a significant discovery of 8.5 million tonnes of lithium has been made in Qahavand, Hamadan. The discovery puts Iran in possession of the largest lithium reserve outside of South America. Furthermore, the Ministry has indicated that there could be even more significant amounts of lithium to be discovered in Hamadan in the future. These developments position Iran to potentially overtake Australia as the top supplier of lithium in the world, although it will be heavily reliant on Iran's diplomatic trajectory.

Background

Lithium is widely referred to as "white gold", similar to petroleum being “black gold”, and is a critical element in the shift towards green energy. It serves as a fundamental component in lithium-ion batteries, the primary energy storage system in electric vehicles (EVs). While lithium-ion batteries have been employed in portable electronic devices for several years, their use in EVs is growing rapidly. By 2030, it is anticipated that 95 per-cent of global lithium demand will be for battery production. However, the price of lithium has been declining for several months, and the recent discovery of Iran's reserve is expected to continue this trend. The extent of the impact on global markets will depend on Iran's ability to export and their production capacity.

Iran's economy is facing significant challenges due to a combination of domestic and international factors. The country has been under severe economic sanctions from the United States since 2018, which has severely impacted its ability to trade with other countries and access the global financial system. The ongoing protests and civil unrest have also taken a toll on Iran's economy. Inflation has been a major problem in Iran, with the annual inflation rate reaching over 40% in 2022. This has led to a decline in the purchasing power of the Iranian currency, the rial, and made it difficult for many Iranians to afford basic necessities.

Analysis

Given Iran's current domestic instabilities, the new find will likely be used as a tool to stabilise the Rial (IRR) which is especially volatile due to international sanctions adversely impacting the country and international political disputes, like the developments linked to the JCPOA. However, as extraction is not planned to begin till 2025, there will not be any real direct short-term economic relief; the government will have to rely on the market’s reaction to future potential.

The discovery will also have diplomatic and foreign policy implications. According to IEA projections, the concentration of lithium demand will be in the United States, the European Union and China. Iran can leverage the necessity of lithium supply to the energy transition and net-zero emission goals as a bargaining chip in future negotiations with Western powers over sanctions relief and its nuclear activities. Iran's growing and diversifying portfolio of essential commodities is a potential threat to those pushing for its exclusion from global trading networks. The new discovery can even act as a catalyst for Iranian membership in BRICS.

China has long-standing economic and political ties with Iran, even amidst Western sanctions. China has been a significant importer of Iranian oil, and in recent years, they have invested heavily in Iranian infrastructure and other sectors. With the discovery of a large lithium reserve in Iran, China is primed to take advantage of its relationship to further pursue its trade interests for rare earth minerals. This could further strengthen the economic ties between the two countries, and also create a new avenue for diplomatic relations. However, the relationship between China and Iran is not without its complications. China's increasing involvement and improved relationship with Iran's regional rivals such as Saudi Arabia has raised concerns in Tehran.

Despite these challenges, the potential economic benefits of the lithium discovery in Iran are significant enough that China is likely to overlook some of these complications and Iran can strengthen its diplomatic ties with political powerhouse. The demand for lithium is expected to increase exponentially in the coming years, particularly in China, which has set ambitious targets for the adoption of electric vehicles. Therefore, the availability of Iranian lithium could be a significant boost to China's domestic EV industry.

A Second Scramble for Africa?: U.S.- China Competition for Rare Earth Minerals

The global demand for rare earth minerals has been on the rise in recent years, driven by the growth of high-tech industries such as electronics, renewable energy, and aerospace. These minerals are a group of 17 elements that are essential to the manufacture of these products, due to their unique magnetic, optical, and catalytic properties.

The global demand for rare earth minerals has been on the rise in recent years, driven by the growth of high-tech industries such as electronics, renewable energy, and aerospace. These minerals are a group of 17 elements that are essential to the manufacture of these products, due to their unique magnetic, optical, and catalytic properties. However, these minerals are found in small concentrations and are difficult to extract, making them a strategic commodity that is vital to the functioning of modern societies.

China is the world's largest producer of rare earth minerals, accounting for more than 80 per-cent of the global supply. This gives China significant geopolitical leverage, as it is able to control the supply and pricing of these critical minerals. In recent years, China has been using its dominant position to assert its influence in global affairs, including trade negotiations and technology transfer agreements. The United States is heavily dependent on China's rare earth minerals, importing nearly 80 per-cent of its total rare earth minerals. This has become a concern for the US government, fearing that China may use its control over rare earths as a tool of economic and political coercion. This fear has only been exacerbated due to the effect the Russo-Ukrainian war has had on crucial commodities and rising tensions surrounding Taiwan. To reduce its dependence on China, the United States has been seeking alternative sources of rare earth minerals, and it has turned its attention to Africa too. Although many African countries already have long-standing mining agreements with China, there has been a recent push to break free from deals some see as not mutually beneficial.

Several African countries, including South Africa, Namibia, and Tanzania, have significant deposits of rare earth minerals. However, the development of Africa's rare earth industry has been hampered by a lack of investment, technical expertise, and infrastructure making it heavily reliant on foreign investment mainly from China. This has left African countries vulnerable to exploitation by foreign companies, who have been accused of prioritising profit over environmental and social concerns.

China has been actively investing in Africa's rare earth industry, seeking to secure its own supply chain and gain a strategic advantage over other countries. As of 2021, Chinese banks made up 20 per-cent of all lending to Africa and in recent years China has been providing African countries with significant technical assistance, including building infrastructure and providing equipment and training for rare earth mining and processing. This investment has given China a foothold in Africa's rare earth industry and has raised concerns about the potential for environmental and social exploitation. During the World Economic Forum at Davos, the President of the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), where 70 per-cent of the world’s cobalt comes from, complained that a $6 billion infrastructure for minerals was heavily one sided, with a majority of the cobalt being processed in China.

These recent signals at a move away from China to potentially better alternatives have not gone unheard by the emerging superpower’s primary rival, the United States. Indeed, the DRC was one of many nations in attendance at the Minerals Security Partnership setup by President Joe Biden and also signed a memorandum with the US in December 2022 to develop supply chains for electric vehicles. In 2019, the US government announced plans to invest in Africa's rare earth industry, with the aim of establishing a reliable supply chain of these critical minerals. These recent acts are just the beginning of what the US government hopes will be a new leaf in their relationship with African countries to develop their rare earth industries and build infrastructure while promoting sustainable mining practices.

The competition for rare earth minerals highlights the need for a global approach to resource management. As the demand for high-tech products continues to grow, the pressure on rare earth minerals will only increase. While some are looking to our solar system’s mineral rich asteroid belt as a way of obtaining these resources, we are most likely decades away from developing the necessary technology and, in the meanwhile, the resources needed to develop said technologies will continue to be fought over. It will take some time before the US is able to really rival China in Africa’s debt markets, but US policy makers are hoping to have made a significant enough dent in China’s hold over the industry before tensions rise any higher between the two world powers.

Copper Shortages and the Transition to Green Energy

Copper, as a chemical element, is one of the most important because it is especially good at conducting heat and electricity, relative to other metals. It has multiple functions, including its use in industrial machinery and electronic equipment or as a raw material in the development and evolution of clean energies.

Copper, as a chemical element, is one of the most important because it is especially good at conducting heat and electricity, relative to other metals. It has multiple functions, including its use in industrial machinery and electronic equipment or as a raw material in the development and evolution of clean energies. Copper deficit for 2023 has already been announced, and it also symbolizes a period of crisis for plenty of projects and industries. The cause is an evident increase in demand and a severe supply constraint.

Supply-side factors

Most of the world’s suppliers are concentrated in Latin America, where the 10 most important mines are located: Chile (3), Peru (3) and Mexico (1). Unfortunately, a series of recent events have led to a shortage in the supply of copper. In fact, problematical political situations in some of these countries have exacerbated the current deficit. Some of them are:

PERU: It represents 10% of the world's copper supply.

As a consequence of the dismissal of Pedro Castillo for declaring the dissolution of the congress and the state of emergency, some unrest occurred in the last few months, affecting about 30% of copper production.

These are the main mines located in Peru:

- Antamina: It is the largest copper deposit in Peru and represents almost 20% of national production. In 2021, an indefinite suspension of operations was declared due to unrest caused by peasant communities blocking access to the facilities.

- Glencore's Antapaccay: This copper mine has been attacked several times in the first month of 2023 and protesters are demanding the cessation of the mine's operations. As a result, the mine temporarily halted its operations.

- MMG's Las Bambas: The mining company has halted and slowed down copper production due to transportation blockages, as in previous occasions what has been generated is an accumulation of production without being able to dispose of it.

CHILE: The major supplier. It represents 27% of the world copper supply.

Increasing environmental regulation has raised production costs in the mining industry and raised barriers to expansion, as happened with the Dominga mining megaproject due to its environmental impact.

Indeed, companies such as BHP Group, Antofagasta PLC y Freeport-McMoRan Inc. have postponed major investments in this business.

MEXICO: The same stance was adopted. Strict environmental mining regulations have stalled up to 25 major projects by freezing new mining concessions and taking a tougher line on the processing of environmental permits.

Therefore, the main causes of the supply constraints are regulatory concerns about their environmental impact and logistic problems related to the capacity to transport supplies (road blockades and protests) and the chaos generated by the protests, which has forced the suspension or interruption of mining companies’ activities.

In addition, during the first week of February, the operations of First Quantum Minerals, which operated in Panama and is considered one of the largest mines in Latin America, were suspended. The inconveniences this time were caused by disagreements with the Panamanian government in the payment of royalties and taxes.

Demand-side factors

The lack of balance between supply and demand is also due to the simultaneous increase in copper consumption in China, driven by a growth in its economic expansion, and its reopening of the market after the pandemic period. China is the world's largest copper consumer and has increased its demand due to the large investments and infrastructure projects that are on the way.

Along the same lines is the global project to move towards a green energy transition. In accordance with the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development (SGD), adopted by the member states of the United Nations and the goals set for 2050, a series of projects have been launched to achieve an efficient energy transition. In light of this planned transiation, copper has become an essential resource as it is essential for the replacement of fossil fuel-based power systems with renewable energy sources.

Therefore, the energy transition has led to a huge demand for copper. Indeed, annual demand will double to 50 million tons by 2035, raising the concern that shortages could result in a reversal of the course of the energy transition. This been seen already in industries such as as construction, manufacturing, architecture. Additionally, the automotive sector’s ability to produce electric vehicles on a large scale will be especially hindered by such shortages.

Summary

The halt in production in the world's main copper-producing regions has exacerbated the impact of increasing demand for copper. Cash-settlement prices for copper listed on the London Metal Exchange (LME) show a rapid increase in copper prices from $5,965 to $8,387 in the period between end of year 2018 to end of year 2022.So far this quarter the LME’s copper cash-settlements peaked at $9.436 on January 18. Experts predict that the price will remain above US$8,500 per tonne for the next few years, with the risk of even exceeding US$10,000.

Unfortunately, a similar situation may occur with other relevant minerals such as lithium and cobalt. In fact, copper experience will be a clear reference for other raw materials in order to find an effective solution.

In the end, it is all about balancing the dilemma between the environmental, social and governance (ESG) practices that are the main challenges of mining and increasing copper production to supply key sectors of the green transition and the economy.

All in all, the supply of copper will be substantially impaired by the following factors:

Copper is a necessary element in many manufacturing and construction industries, added to the growing demand in renewable energy projects that use this element as part of the transition.

The demand for copper from high consuming countries such as China will cause the supply and demand balance to become more unbalanced if a controlled supply solution is not found.

The lack of consensus between the private sector, the public sector and communities around mining will maintain the constant blockades and protests in the main copper-supplying cities in Latin America.

Environmental regulation is increasingly relevant for the development of the mining activity but has become a barrier to its operation.

The cessation of activities of the main mining companies abruptly generates a deficit in the copper supply, which has a direct impact on the price of copper, given the scarcity situation, expanding the damage caused by the initial problem.

Analysing the Volatility of Coal Prices: Why they Spike in Fall

Coal prices have a tendency to peak in the fall. A variety of factors contribute to this phenomenon. Understanding the underlying causes of this can help inform policy decisions and investment strategies related to coal.

A major factor that affects coal prices is the seasonal demand for energy. As the weather gets colder in the fall, there is an increase in demand for heating which in turn leads to an increase in demand for coal as a fuel source. The increase in demand drives up the price of coal. For example, in the United States, coal consumption for electricity generation tends to increase during winter months as the demand for heating increases. Historical data shows coal prices tend to increase in the months of October and November, as the weather gets colder.

Another factor that contributes to the higher coal prices in autumn is the timing of industrial production. Many industries, such as steel and aluminium sectors, have a seasonal cycle where production increases in the fall. Higher production levels lead to an increase in demand for coal, which drives up prices. For example, in China, a major consumer of coal, steel production typically increases in the fall as demand for construction materials increases. This increased demand for coal can be seen in the historical data, with coal prices tending to increase in the months of September and October, when industrial production increases.

Additionally, supply-side factors also play a role in the peak in coal prices in the fall. For example, in some regions, fall is the time when mines are closed for maintenance and this reduces the supply of coal. This then contributes to higher prices. Furthermore, natural disasters such as floods and typhoons can disrupt coal mining operations, leading to a temporary shortage, again driving prices higher. Among the most important, and also potentially the most overlooked is the nature of monsoon rains in India, and their subsequent effects on the supply of coal. India is second largest producer and consumer of coal in the world after China, with production being 778 million tonnes and consumption being 1052 million tonnes; with it seeming to increase for the short term (till 2030) peaking at about 1192-1325 million tonnes. Coal is a critical fuel source for the country's power plants, factories, and households, accounting for over half the country’s energy needs. The monsoon season typically occurs between June and September and often has major impacts on coal production and transportation. For instance, the Piparwar Area in 2019, which is known for its overwhelming share of coal mining in the country, was hit by severe flooding causing a halt in production, leading to supply crunches. In areas where mines are located near rivers, the monsoon rains can cause flash floods that then completely inundate the mines, making it impossible to extract coal. In addition, the heavy rainfall can cause landslides and washouts along transportation routes, making it difficult to transport coal from mines to power plants, ports, and other destinations.

In conclusion, the peak in coal prices in the fall is the result of a combination of factors such as seasonal demand, industrial production cycles, and supply-side constraints. By analysing historical trajectories, one can assess the impact each of these factors have had to drive the fall peak in coal prices over time. This knowledge can help inform policy decisions, investment strategies related to coal and can also be used to predict future price trends.

EU ban on Russian oil products – what will the fallout be?

On February 5th, 2023, the EU imposed a further price cap on Russian petroleum products. This comes after the decision, in December 2023, to set a threshold price for Russian crude oil shipped by sea at $60 per barrel. In particular, the new price cap will apply to “premium-to-crude” petroleum products, such as diesel, kerosene and gasoline, and “discount-to-crude” petroleum products, like fuel oil and naphtha. The maximum price agreed on by EU leaders for the former is $100 per barrel and the latter, $45 per barrel. The move is being undertaken by the EU and other G7 countries. This spotlight will focus on the fallout of the price caps on oil products.

Firstly, Russia, which is the second largest oil exporter in the world, will see a decrease in its fiscal revenues in the coming months. Earnings from oil and gas-related taxes and export tariffs accounted for 45 percent of Russia’s federal budget in January 2022. Contrary to embargoes, the price caps implemented by the EU ensure Russian oil products keep flowing into the market, whilst starving Moscow of revenue. In January, Russia’s government revenues decreased by 46 percent compared to last year and government spending surged due to higher military spending. A study by the Centre for Research on Energy and Clean Air reported that Russia is already losing $175 million a day from fossil fuel exports. The new price caps enforced in February will likely reinforce this trend and contribute to the widening Russian deficit, which was $25 billion in January. In response, the Kremlin might increase the shift of its oil product exports to China, India, and Turkey, which collectively now make up 70% of all Russian crude flows by sea and have so far contributed to partly offset the impact of Western sanctions on the Russian economy. At the same time, Moscow might scale up its efforts to bypass price caps imposed by G7 nations through its growing “ghost fleet”, which in January moved more than 9 million barrels of oil. However, these new importers have acquired considerable leverage vis-à-vis Russia. As Adam Smith, former sanctions official with the US Treasury Department, put it “Am I going to buy oil at anything above [the price cap], knowing that’s the only option Russia has?”. This might mean that, even if the Kremlin succeeds in re-orienting its exports of oil products to these new destinations, it will do so at lower prices.

On the other hand, the EU may face a diesel deficit in the coming months. In 2022, Russia accounted for almost half of the EU’s diesel imports, corresponding to around 500,000 barrels per day of the fuel. This will push European countries to try to step up imports of diesel from the US and the Middle East in order to avoid a spike in diesel prices. High fuel prices are politically sensitive and have contributed to high inflation rates across the EU. New trade flows in oil products from these regions could lead to a spike in clean tanker rates, which would increase delivered fuel costs in Europe. Tanker rates from the Middle East to the EU were already close to a three-year high at $60/tonne in January. They are expected to double this year. Moscow has responded to the EU price caps by cutting its oil output by 5 percent, or 500,000 barrels a day. Headline inflation in the eurozone has decreased for the third consecutive month in January but the threat of a rebound in inflation in the near future still looms large.

In such a case, the prospects for an increase in social tensions would become more concrete. Already in September of last year, due to the rising cost of living, protesters in Rome, Milan, and Naples set fire to their energy bills in a coordinated demonstration against escalating prices. In October, thousands of people marched through the streets of France to express their dissatisfaction with the government's inaction regarding the cost of living. In November, Spanish employees rallied together chanting "salary or conflict" in demand of higher wages. However, an increase in salaries would risk pushing up prices even more, thus jeopardising the European Central Bank’s efforts to bring inflation under control.

Powering the future: Lithium in the EV battery value chain

Powering the future: Lithium in

the EV battery value chain

This research paper is the first in a series covering the numerous risks associated with electric vehicle (EV) battery production. Each paper delves into a specific mineral that is vital to this process, starting off with lithium. This series is brought by a team of analysts from the Global Commodities Watch.

REPowerEU, Piano Mattei, and the Political Economy of the Mediterranean

From the Phoenicians to the First French Republic, two shores of the Mediterranean have been the cradle for many important ancient civilizations, including the Carthaginians and Ancient Egyptians. Although in modern times the post-war political alignments and government institutions look very different, the evidence of a rich common history can be seen all over Southern Europe and North Africa in the forms of enclaves, architecture, and shared cultural and linguistic norms. Following Giorgia Meloni’s state visits to Algeria and Libya, this spotlight considers how Italy’s Piano Mattei (Mattei plan) can be an opportunity for the rest of the European Union (EU) to successfully implement the REPowerEU energy plan and potentially rekindle trans-Mediterranean trade and cooperation, beyond natural gas and energy markets.

Immigration, Energy Markets, and Fratelli d’Italia: What is Piano Mattei?

In simple terms, Piano Mattei represents Italy’s de facto foreign policy in the Mediterranean under Giorgia Meloni’s tenure as President of the Chamber of Deputies (the official title of the head of the Italian government). The origins of Mattei can be found in Fratelli d’Italia’s (FdI) manifesto for the 2022 Italian general election, which stresses FdI’s belief that Italy must once again become a leader in energy markets. Piano Mattei takes its name from Enrico Mattei – founder of Italy’s state-owned hydrocarbons agency: Ente nazionale idrocarburi (Eni). During his time in the Chamber of Deputies, and later as Chairman of Eni, Mattei realised that if Italy wanted to include natural gas in its energy mix then Italy needed to cooperate with key exporters. Indeed, Mattei oversaw the signing of various bilateral agreements with many newly-independent states in the MENA region to import natural gas to Italy. Mattei’s work with Eni was also crucial to the construction of the Transmed pipeline, which channels Algerian natural gas to Sicily via Tunisia. The plans for the Transmed pipeline also included the Maghreb-Europe pipeline, which exported Algerian gas to the Iberian Peninsula until last October, when Algiers elected to not renew its export contracts with Morocco over increasing tensions over the Western Sahara conflict. This effectively ceased the flow of natural gas from Algeria to Iberia.

Giorgia Meloni formally introduced Piano Mattei last December, during the eighth iteration of the Dialoghi Mediterranei di Roma – a forum on Mediterranean politics hosted by Italy’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs and International Cooperation alongside the Instituto per gli studi di politica internazionale (ISPI), a prominent Italian thinktank. In Meloni’s own words, Piano Mattei is a “virtuous collaboration leading to the growth of the European Union and African nations” guided by the principles of “interdependence, resilience, and cooperation”. Naturally, the namesake “Mattei” suggests that Meloni’s stance is primarily to secure energy supplies for Italy and totally eliminate the dependence on Russian natural gas. On the one hand, however, Meloni’s foreign policy in the Mediterranean also aims to build upon the European Commission’s trade ambitions with the ‘Southern Neighbourhood’: “The long-term objective of the trade partnership between the EU and its Southern Neighbourhood is to promote economic integration in the Euro-Mediterranean area, removing barriers to trade and investment” and the EU’s wider energy policy goals. On the other hand, Associazione Amici dei Bambini – an Italian children’s rights NGO – raises the concern that Meloni’s ambiguous and rhetorical references to immigration in her keynote speech at the Dialoghi Mediterranei di Roma, suggest that perhaps Meloni’s ambitions are centred on delivering campaign promises regarding trans-Mediterranean migration flows. Indeed, Meloni’s lexical and rhetorical ambiguity is often the cause for concern for some analysts (including the author of this spotlight). Whether Meloni intends to use Mattei to further her immigration policies is difficult to ascertain at this stage, and is beyond the scope of this spotlight.

Regardless of how one may interpret the scope or intentions of Mattei, one thing is certain – it can be an opportunity for all of the Mediterranean countries. For Italy (and to a large extent, Meloni) it would be a first step in re-establishing itself as a regional economic powerhouse and help move away from decades’ long economic stagnation. For Algeria and other North African countries, the prospect of increased cooperation and interdependence with the EU is an incentive for investment, potentially beyond natural gas and energy markets. In the two weeks after Meloni’s visit to Algiers on January 24 2023, Eni’s (Euronext Milan) share price increased 4.58 per-cent from €14.18 to €14.83. Year-to-date growth is around the 8 per-cent mark, at time of writing.

Limits for the European Commission and Meloni’s Government

Although a more collaborative and economically interdependent Mediterranean could have the potential to benefit states on either side, Giorgia Meloni and the European Commission need to learn from the past if they are to derive short-term economic benefit as well as long-term regional cohesion. What is meant here by “learning from the past” is that ‘switching’ who is supplying the EU with gas from Russia to Algeria, for example, does not account for the weakness in Europe’s energy strategy before the Russo-Ukrainian War. That is, relying on a weakly-integrated trade partner for a crucial commodity.

The REPowerEU plan outlines the EU’s energy policy following the Russian invasion of Ukraine. Although the medium to long-term impetus is to increase the role of renewables within the bloc’s energy mix, the short-term imperative includes securing hydrocarbons from non-Russian suppliers. These two foreign policy goals are not necessarily ad diem, and in the context of the Mediterranean, actually involve compromising successful economic interdependence between the EU and its ‘Southern Neighbourhood’.

To contextualise; on January 19 2023 Resolution 2023/2506 was adopted by the European Parliament, calling upon the Kingdom of Morocco to “release all political prisoners'', including the release of Nasser Zefzafi, and to “end of the surveillance of journalists, including via NSO’s Pegasus spyware, and to implement legislation” which protects journalists. Further, increasing collaboration with Algeria (who, as above mentioned, is having its own political standoff with Morocco over Western Sahara) suggests that the short and medium-term ambitions of REPowerEU and Piano Mattei are at odds with the European Parliament’s adoption of Resolution 2023/2506. This is problematic for securing natural gas supplies to Iberia and the westernmost corners of the bloc, but potentially for regional stability in general. If the EU cannot strike the right balance between appeasing Algerian requests and reprimanding Morocco for its treatment of journalists, the prospect of tensions between the two North African states cooling off is not particularly positive. This indirectly impacts the operations of the Maghreb-Europe pipeline, and so on. Indeed, on January 23 2023 the Moroccan parliament “voted unanimously” to reconsider its ties with the European Parliament.

That said, Morocco-European relations are not exactly at an all time low – in terms of trade and commerce, at least. Trade between the EU and Morocco has increased significantly in the period between 2011 and 2021, and the North African state is the bloc’s 19th largest trading partner. Morocco is also among the top African trading partners for Greece, Italy, Portugal, and Spain. Therefore, there is still space for Morocco-Europe relations to improve within the broader scope of REPowerEU, the European Commission’s ‘Southern Neighbourhood’, and of course, Giorgia Meloni’s Piano Mattei.

Summary: Implications for the Political Economy of the Mediterranean

As the EU gravitates towards North Africa to ‘de-Russify’ its natural gas imports what diplomats and politicians should keep in mind two things: (i) the current tension between Algeria and Morocco, and (ii) diversifying gas imports is not (in the short-term) compatible with holding Morocco politically accountable for its mistreatment of journalists. It is an unlaudable conclusion, of course. But certain international relations theory – namely liberal institutionalism – would defend this claim as the theory emphasises understanding “the role that common goals play in the international system and the ability of international organisations to get states to cooperate,” as opposed to focussing strictly on power relations between states.

In the case of Mattei as a part of the EU’s ‘Southern Neighbourhood’ strategy, turning to the Mediterranean region means understanding the political tensions of North Africa in order to ensure the best outcomes for REPowerEU and Mattei, as well as avoiding antagonising the Kingdom of Morocco – even if the normative reasons for doing so are justified. Within the EU, the success of Piano Mattei in increasing Algerian gas supplies to Italy and the rest of the Transmed pipeline (which terminates in Slovenia) is intricately linked with REPowerEU’s short-term goals. Thus, as Arturo Varvelli elaborates in his commentary on the issue, Brussels and Rome ought to conduct themselves in a cooperative manner to ensure the success of Mattei and REPowerEU alike. If not, Meloni’s well-documented Euroscepticism could well be weaponised and used against Brussels, which would be a counterproductive outcome for Italy and the EU’s political legitimacy.

On these premises, then, the EU’s ‘Southern Neighbourhood’ strategy should also encompass the goals of REPowerEU to, first of all, secure alternative gas supplies, but also to cosy up to Rome and using the increased demand for non-Russian natural gas to quell Algiers-Rabat tensions. Equally, in pursuing the energy goals of Piano Mattei Giorgia Meloni should also consider using Italy’s diplomatic power to help find a solution that might reopen the Maghreb-Europe pipeline if she desires to obtain a reputation for closing deals and power brokering at the European level.

Outlook

Italian-North African gas exploration and trade deals may face significant challenges in the shape of Europe’s green energy transition.

Meloni will most likely be able to secure the ‘de-Russification’ of Italy’s natural gas supply, but whether this will hamper Rome’s green energy transition remains to be seen.

Forecasts would suggest that LNG futures prices will not fluctuate sufficiently to dampen the value of natural gas trade between Italy and its partners, Algeria and Libya, in North Africa.

Whether Meloni aims to cooperate with, or conspire against, the EU’s short and long-term energy policies remains to be seen.

At the present moment it is very unlikely that Algeria-Morocco relations will improve to the point of reopening gas flows to Iberia via the Maghreb-Europe pipeline. How the situation between both states remains a critical point for the energy policies of Italy and the EU at large.

Image Credits: ROSI Office Systems Inc.

All eyes on Algeria: how natural gas is shaping North-African politics

One country in North-Africa seems to be making the most out of the current energy crisis and a new era in great-power rivalry - Algeria. Great potential has fuelled massive interest in the country’s gas industry and led to a significant increase of gas revenues in the past years. As a consequence, the country is able to spend big, both domestically and abroad, and charter a more active foreign policy. The latter, however, is held under increased scrutiny by parliamentarians and senators across the Atlantic, raising questions about the risks of Algerian gas imports. Another question, which is worth asking, is to what extent Algerian gas potential can be turned into actual export flows.

This analysis will take a deep-dive into 1) the drivers of increased interest and cooperation in Algeria, 2) the outcomes so far, and 3) complications and geopolitical dynamics, after which a small outlook will be presented.

Drivers of increased interest and cooperation in Algeria

Increased interest and cooperation in Algeria and North Africa are partly driven by the war in Ukraine and the need to source new gas supplies. In a bid to curb Russian gas imports, both European and international energy companies are scrambling supplies across the globe. Before the war, Russian natural gas accounted for roughly 45% of EU imports or 155 bcm, whereas it is now standing at roughly 10% of EU imports or 34.4 bcm. That leaves a gap of roughly 120.6 bcm to satisfy demand. And while some supplies may be curbed by lowering demand through the increase of energy efficiency and the usage of other fuels, most will have to be sourced elsewhere.

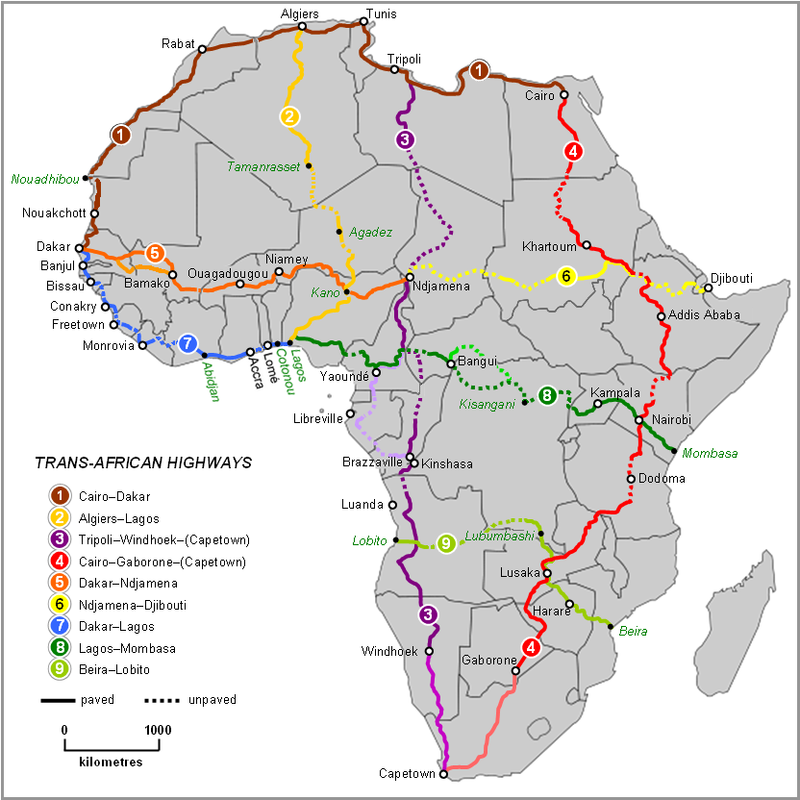

Algeria, as a source of natural gas, offers much potential. It is Africa’s largest natural gas exporter and in combination with its location, the country could offer an ideal place to source gas. Algeria’s potential has led to increased interests in its gas industry. Other countries in North Africa, including Libya and Egypt, have also received increased interest. Notably, Libya secured an $8 billion exploration deal with Italian energy major Eni.

*Note that the Trans-Saharan and Galsi potential or planned pipelines.

Algerian gas market: Facts and Figures

Reserves: The country holds roughly 1.2% of proven natural gas reserves in the world, accounting for 2,279 bcm.

Production: Its production stands at 100.8 bcm per year.

Exports: In 2021 it exported 55 bcm, 38.9 bcm through pipelines, and 16.1 bcm in the form of LNG. European imports accounted for 49.5 bcm, 34.1 bcm by pipelines, and 15.4 bcm in the form of LNG.

Export capacity: Algeria has a total export capacity of 87,5 bcm: the Maghreb-Europe (GME) pipeline (Algeria-Morocco-Spain) 13.5 bcm, Medgaz (Algeria-Spain) 8 bcm, Transmed (Algeria-Tunisia-Italy) 32 bcm, LNG 34 bcm.

Aside from potential, ambition (on both sides of the Mediterranean) is another reason for interest and cooperation. Interest has come from the EU and several member states, but mostly from Italy. Instead of merely securing gas supplies, Italy aims to become an energy corridor for Algerian gas in Europe. This will boost Italian significance in the European energy market, increasing both transit revenues and investment in its own gas industry. Moreover, Rome seeks to increase its profile in the Mediterranean, mainly to stabilize the region and decrease migration flows. It views both Algeria and its national energy firm Eni as key factors in that aim.

Algeria is also looking for a more active role in the region. For the past years, the country has been emerging from its isolationism, which characterized the rule of president Bouteflika, who was ousted in 2019. With new deals and increased gas revenues it hopes to increase defense and public spending, prop-up its gas industry, which suffered from lack of investment, and stabilize its economy and the region. Aside from economic reasons, therefore, cooperation between the two sides is politically motivated as well.

What has this increased interest and cooperation so far led to?

As a result of increasing gas prices and rising demand, the Algerians have seen their revenues increase massively. Sonatrach, Algeria’s state-owned energy company, reported a massive $50 billion energy export profits in 2022, compared to $34 billion in 2021, and $20 billion in 2020. This will allow for more fiscal space and public spending. In fact, the drafted budget of 2023 is the largest the country has ever seen, increasing 63% from $60 billion in 2022 to $98 billion in 2023. Because of bigger budgets, Algeria will also be able to partly stabilize its neighbors by offering electricity and gas at a discount - something the country is currently discussing with Tunisia and Libya.