The Future of Infrastructure Investment in Africa

The investment landscape in Africa is undergoing a significant transformation, shaped by a high-interest rate era, evolving geopolitical dynamics, and the continued demand for energy and infrastructure projects. As investors navigate Africa’s financial markets, a rise in public-private partnerships, especially in green energy, will likely be the trend moving into the future. China has played a crucial role in funding energy and infrastructure projects so far, but recent developments suggest that Beijing is altering its approach in response to its own economic woes and the re-election of Donald Trump. With negotiations on peace in Ukraine and Gaza ongoing, the world’s attention could soon be turning to Africa..

A Changing Investment Climate

In Africa, the demand for large scale infrastructure investments remains high, yet capital remains constrained by perceived risks and a lack of well-developed secondary markets for investors. While in traditional investments shareholders can sell off their assets on the stock market (or to other private investors), there are few options for investors wishing to sell their shares of infrastructure developments. Therefore, many early-stage investors in critical infrastructure projects, including renewable energy projects, struggle to find viable exit strategies. Development finance institutions, who usually provide much of the financing for these projects, often find themselves unable to sell off their shares in projects and reallocate their capital.

One solution for this is the UK-backed MOBILIST (Mobilising Institutional Capital Through Listed Product Structures) programme. The programme takes inspiration from REITs (Real Estate Investment Trusts), which are used in the real estate market to pool assets together, making them more accessible to investors. MOBILIST has developed a similar investment vehicle called ‘Yield Cos’, which acquire operational infrastructure and energy projects, lowering the risk for investors while also allowing early-stage investors to reinvest their capital. While the initiative has not totally eased investors fears, it is a step towards Africa bridging its financing gap.

Despite volatility, African stock markets remain attractive for retail and institutional investors, and alternative investments, ranging from private equity to infrastructure funds, are becoming more mainstream. While the re-election of Trump can be seen as a knock to the pro-ESG (environmental, social, and governance) camp, sustainable investments, especially in emerging markets, could provide both safe financial returns and positive social impact.

Cost of Capital

China has been the dominant player in African infrastructure financing for over two decades, providing approximately $182 billion in loans across the continent. Historically, China would use one of its three “policy” banks, Export-Import Bank of China, Agricultural Development Bank of China, or the China Development Bank, to fund infrastructure projects, which would then be built by state-owned enterprises (SOEs). However, this model is no longer sustainable due to a variety of reasons, such as China's economic slowdown and Africa’s increasing debt sustainability issues. The shift was demonstrated during the 2024 Forum on China-Africa Cooperation (FOCAC), where Beijing announced a financing package of $51 billion, including a significant portion dedicated to equity investments. Despite this being a substantial amount, it is lower than previous packages, especially as the financing will be spread over a three year period . With African nations increasingly advocating for equity financing, Chinese firms will now more frequently have to participate in competitive bidding systems rather than rely on closed door negotiations. Furthermore, if they win contracts they will now be stakeholders and not just lenders, meaning they will have more of an interest in the long term maintenance of projects.

The Green Transition

The 2025 China-Africa Cooperation Beijing Action Plan stated that new investments will have a focus on green energy development. This is not entirely new news, as in 2021 Beijing announced it would stop funding new coal power projects as part of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), redirecting its focus toward renewable energy. Since then, China has used its domestic expertise to increase financing for solar, wind, hydroelectric, and green hydrogen projects. It has also stated its desire to develop nuclear energy projects across the continent. The Export-Import Bank of China (EXIM) and the China Development Bank (CDB) continue to drive much of this financing, with a new emphasis on smaller, environmentally friendly projects. The recent Chinese pivot toward the “small is beautiful” approach, the phrase used Xi Jinping’s keynote speech at FOCAC, further illustrates Beijing’s new lower appetite for risk. The BRI has been successful for both China and Africa, as China was able to redirect capital and expertise to aid African nations in their modernisation efforts.

Now at the forefront of developments in green energy technology, China is well placed to continue utilising the BRI to build green infrastructure in Africa. Despite increased commitment to renewable energy, challenges remain. African nations still face barriers in raising funding for renewable energy projects, as key stock markets in Nigeria, South Africa, and Kenya have yet to provide low risk investment vehicles to attract capital. While Yield Cos could help alleviate these worries, they are still relatively new investment vehicles and lack the trustworthy profile that is needed to attract large scale institutional investment.

The Role of Private Sector

Due to its economic slowdown, China has pushed for its private sector companies to become more involved in Africa. Between 2015 and 2021, non-policy bank creditors provided approximately $55 billion in financing, making up one-third of China’s total spending in Africa over this period. Where these firms differ from policy banks, is that policy banks aim to implement specific government policies rather than pursuing profit as commercial banks do. Unlike state-backed loans, financing from commercial creditors, such as the Industrial and Commercial Bank of China (ICBC), is faster and less bureaucratic, despite these institutions still being largely owned by the Chinese government. While policy banks can take several years to commit capital after rigorous negotiations, financing from commercial creditors can be obtained within a year. In some cases, these lenders have provided bridge loans to sustain projects while awaiting funding from policy banks.

However, this also highlights one of the main negatives of commercial loans, which is the much shorter time period that creditors want to be involved for. This means that their loans carry higher interest rates and shorter repayment periods, exacerbating short term debt burdens for already struggling African nations. This has been made worse by the recent era of high interest rates and by the fact that the majority of Chinese financing has gone to countries facing debt sustainability issues. Furthermore, they require sovereign guarantees and insurance from China Export and Credit Insurance Corporation (Sinosure), which increases overall borrowing costs. The risk coverage Sinosure provides has also been cut back for countries that have defaulted. With the Chinese financial sector already risk averse due to their exposure to the ongoing domestic real estate crisis, private creditors will be less amenable to debt restructuring than policy banks are. This is because policy banks have to consider China’s geopolitical relationships while private creditors are profit driven. Despite these negatives, China’s willingness to provide equity financing indicates its long-term strategic commitment to close financial ties with Africa.

Western Response

Beijing adapting its strategy to align with both African goals and its own domestic constraints will likely mean that it maintains its dominant position on the continent. While its European counterparts have undertaken projects like MOBILIST and the Sustainable Energy Fund for Africa (contributing states being Denmark, the UK, Spain, and France), Europe’s focus is on rearming in anticipation of standing against Russia without American backing.With Western Europe having to make stricter fiscal decisions in the face of potential economic stagnation, they are unlikely to close the financing gap they have with China in Africa.

Under a second Trump administration, the US is expected to take a more aggressive stance in countering Chinese investments in Africa. USAID has had most of its operations halted and is anticipating a significant shift in its policies once the administration’s 90 day review of USAID is complete. This has and will very likely involve cutting funding to countries that engage with Chinese entities, directly or indirectly, reinforcing Trump’s America First foreign policy. Trump’s emphasis on deal making and the involvement of the US private sector may be to Africa’s benefit, as a transactional approach could allow financing to go ahead with little of the red tape associated with the international NGOs that usually acquire USAID funding to operate in Africa. His nomination of Benjamin Black, whose experience lies in finance rather than foreign policy, to lead the US international Development Finance Corporation (DFC) solidifies this transactional approach, prioritizing economic returns over traditional aid diplomacy. Additionally, US support for fossil fuel rich nations, such as Tanzania and Nigeria, contrasts sharply with the previous administration’s green energy focus, further distinguishing its investment strategy from China’s renewable heavy initiatives. With this in mind, we will likely see African nations reliant on or rich in fossil fuels aligning with the US, while those focusing on green energy will likely become closer to China.

Conclusion

While Trump could force a clearer alignment of countries currently taking advantage of funding from both the West and China, a significant incentive that China maintains is political stability. The switch from Biden to Trump was tantamount to political whiplash, which countries like South Africa are currently learning the hard way. The US cut $1 billion in loans that were employed to facilitate South Africa’s transition to green energy as part of a growing political spat between the two nations. African countries who could stand to benefit from US investments in its fossil fuels could be deterred by the possibility of a Democratic administration reversing Trump policies. Though China is decreasing the size of its investments, it remains a steady and predictable partner. In addition to this, US warnings of Chinese debt-trap diplomacy will likely fall on deaf ears as there have been no clear-cut cases so far of China leveraging debts to force nations into one-sided agreements. However, the introduction of Chinese private firms more concerned about profit than politics could see this change and may finally give the US the edge it desperately needs in Africa.

The Risks Presented by Poverty, Inequality and Unemployment in South Africa

Executive Summary

London Politica assesses with high confidence that increased poverty, unemployment, and inequality levels will likely continue to drive crime, unrest, and the rise of populist parties in South Africa. This will likely negatively impact the perceived legitimacy and support of the Government of National Unity (GNU) coalition.

To address these challenges effectively and maintain popular support, we assess that the GNU would benefit from investments in infrastructure targeting electricity and water supply, as well as social programs, education and poverty alleviation initiatives at the local level. The implementation of structural macroeconomic reforms to improve living standards and public sector efficiency would also likely continue to improve the country’s business climate and attract foreign investment.

Declining unemployment rates are expected to strengthen demand-driven growth, as evidenced by the 1.3% increase in household consumption following the election. This will likely reinforce business confidence and accelerate the expansion of key national industries, including mining, construction, manufacturing and electricity.

Despite growth in key domestic sectors, economic activity declined across government consumption, imports and exports, contracting GDP by 0.3% in Q3. Persistent trade weakness, driven by declining imports of minerals, precious metals and machinery will likely further constrain trade flows in the near term, limiting the GNU’s external growth prospects.

Introduction

South Africa remains one of Africa’s most advanced and diversified economies offering a relatively stable investment environment. Its appeal to foreign investment lies in its world-class financial services, deep capital markets, transparent legal framework and abundant natural resources. Key sectors attracting foreign direct investment (FDI) include manufacturing, mining and financial services. Despite ample investment opportunities, FDI inflows have consistently declined since 2022, dropping from $1.3 billion in the first quarter of 2024 to $965.87 million in the second quarter.

Throughout 2024, South Africa’s economy faced significant disruptions due to persistent electricity shortages, civil unrest and logistical challenges. These factors - coupled with the outcome of national and provincial elections - substantially impacted business confidence, as the South African Chamber of Commerce’s Business Confidence Index (SACCI) declined by 6.9 points over the two months following the May 2024 general election.

The 2024 general elections marked a historic shift in South Africa’s political landscape, as the African National Congress (ANC) lost its 30-year parliamentary majority, securing a record low of 159 seats. This led to the formation of a coalition government, the Government of National Unity (GNU), composed of 10 parties collectively holding 287 of 400 seats (72%) in the National Assembly. The Democratic Alliance (DA), a pro-business party and the main opposition to the ANC, emerged as a key coalition member, securing 87 seats in the National Assembly.

By prioritizing economic growth and a stable business climate, the GNU has gradually bolstered business confidence through its commitment to implement structural economic reforms and enhance public sector performance. The joint initiative between the presidency and the National Treasury dubbed “Operation Vulindlela” aims to transform electricity, water, transport and digital communication infrastructure to promote economic growth and attract foreign investment.

Within six months of the general election, economic growth and investor confidence are gaining momentum, driven by anticipated structural economic adjustments in energy, logistics and the public sector. The South African Reserve Bank reported the first net inflow of capital since 2022, shifting from an outflow of $1.1 billion in Q2 of 2024 to an inflow of $2.1 billion in Q3. This shift reflects renewed investor confidence in the country’s economic stability, as evidenced by increased inflows of direct investments, portfolio investments and reserve assets.

While the business climate shows signs of improvement, the GNU is likely to face multifaceted risks associated with unemployment, poverty and inequality. South Africa’s high unemployment rates - particularly among young people - create profound negative externalities for the state, as the country’s demographic dividend is disproportionately wasted due to a lack of investment in human capital development. Although 22,000 jobs were created in 2024, 137,000 South Africans entered the workforce the same year. The expanded unemployment rate (including discouraged seekers) was 60.8% amongst 15-24 year olds in Q2 of 2024. As unskilled and unemployed working-age adults are consistently delinked from the labour force, a long-term skill gap is latching itself into the employment market. This risks snowballing into a structural unemployment problem whereby individuals lack the skills necessary to bridge the gap toward average employment requirements.

Unrest

South Africa continues to grapple with worsening civil unrest; data illustrates a visible increase in registered protests and riots since 2021. Civil unrest poses significant risks to both the economic and security environment, leading to financial losses, disruption of business operations, and widespread property damage.

Unrest represents an operational hazard for foreign stakeholders and frequent business disruptions continue to damage the GNU’s legitimacy. These trends are likely to persist unless underlying economic issues are effectively addressed.

The July 2021 riots led to $1.5 billion in economic losses and two million jobs being lost or impacted for both local and foreign companies.

Our analysis of historical trends indicates that politicians' failure to appropriately address long-standing unemployment, inequality, and infrastructure deficits have driven grievances and unrest across the country.

Civil unrest remains a key issue obstructing social and economic development in South Africa. South Africa ranked 127 out of 163 on the Institute for Economics and Peace’s (IEP) Global Peace Index 2024, putting it amongst the fifteen most politically unstable countries in Sub-Saharan Africa. Civil unrest increased significantly last year, with 692 protests and riot incidents registered during the first quarter of 2023 compared to 456 over the same period in 2022.

Historically, analysts have associated civil unrest in South Africa with popular resentment towards high and stagnant levels of unemployment and inequality, which are amongst South Africa’s most critical and longstanding socioeconomic challenges. Unemployment increased from 21.8 percent to 28 percent between 2013 and 2023, with the World Bank describing it as “South Africa’s biggest contemporary challenge” in October 2023.

Moreover, South Africa has some of the highest income and wealth inequality levels globally. The population’s richest decile accounts for about 65 percent of national income while the poorest half accounts for 6 percent. Disillusionment towards politicians has historically grown amongst South Africans as governments fail to confront unemployment and inequality, particularly along racial lines.

In July 2021, former South African president Jacob Zuma was arrested in Estcourt, KwaZulu-Natal, after refusing to appear before a judicial commission investigating corruption during his decade in power. Zuma's incarceration led to the violent 'Free Zuma' protests, which escalated and spread to other areas of the country including major cities such as Johannesburg. The riots constituted the largest period of civil unrest since the end of the Apartheid, with an estimated 354 people losing their lives. In our analysis of related data and interviews conducted by local news sources, we assess these protests were largely driven by background economic grievances.

Although the riots in July 2021 were precipitated by Zuma’s arrest, enquiries conducted in the aftermath illustrate that the causes were more deep-rooted. The South African Human Rights Commission (SAHRC) found that high unemployment rates, inequality and poverty were the bedrock from which unrest permeated. Echoing the findings of the SAHRC’s investigation, South Africa’s Minister of Trade, Industry and Competition Ebrahim Patel stated that “while it was true that there were those with a different agenda who lit the match, that match was thrown on dry tinder in communities where there was severe unemployment and poverty”. Further, protests led by the trade union groups Congress of South African Trade Unions (COSATU) and the South African Federation of Trade Unions (SAFTU) over the cost of living and unemployment rates erupted in Pretoria and Cape Town in August 2022, and Johannesburg in July 2023. In late November 2024, residents clashed with police in Johannesburg over a lack of water supply, demonstrating risks of public dissatisfaction with infrastructure deficits.

Previous civil unrest in South Africa has driven security and economic implications that were detrimental enough to shift the risk perceptions of foreign investors and other overseas stakeholders. The ‘Free Zuma’ riots led to $1.5 billion in economic losses and two million jobs being lost or impacted at both local and foreign companies. Unrest primarily disrupts the transportation of goods as major road closures.

Protesters blockaded and damaged key sections of the N2 and N3 highways, significantly disrupting commercial traffic in the KwaZulu-Natal region (KZN) along routes critical to national and regional logistics networks. The closure of these strategic routes constrained commercial cargo traffic and transit freight, disrupting supply chains that link South Africa with landlocked African countries which resulted in significant shortages in food, fuel and medical supplies. In the aftermath, foreign investors cited these riots as a deterrent to new investments and the expansion of existing ones. The economic cost of violence in South Africa as a percentage of GDP amounted to 15.38 percent in 2023.

Assessment:

London Politica assesses that high unemployment and inequality are likely to stagnate or worsen without effective government investments in energy, telecommunication and water supply networks. The absence of effective social investments increases the risk of unrest, particularly in urban areas and neighbourhoods with higher poverty rates. Such unrest is likely to undermine the government’s legitimacy, as constrained economic growth and high unemployment erode support for the GNU’s coalition in favour of populist parties.

The GNU should enact structural reforms to address unemployment, infrastructure deficits, and public sector performance to prevent consequences associated with a declining investment climate. The government’s pledge to address supply-side challenges by boosting investments in electricity infrastructure will likely gradually improve economic productivity and foreign investment in the long term. Although enhanced electricity supply bolstered manufacturing outputs in 2024, persistent social unrest linked to infrastructure deficits remains deeply entrenched and is unlikely to be resolved in the short term.

We assess that disenfranchised South Africans are likely to turn to disruptive demonstrations to voice their grievances against the government’s lack of effective investment. Social unrest will likely continue over the GNU’s term, resulting in occasional infrastructure damage and substantial financial losses to cities and towns across the country.

Crime

South Africa faces high crime rates linked to socio-economic problems which are exacerbated by the ineffective use of resources. Crime and violence divert resources away from development programs, investments in infrastructure and crucial social services as the government focuses instead on immediate security measures.

This misallocation of resources fails to address the root causes of crime and contributes to social inequality. Important sectors like education and economic development are underfunded due to the focus on short-term security.

The problem is cyclical, with short-term security priorities hindering long-term development and prolonging instability.

Crime in South Africa has a very significant impact on foreign investment and capital inflows. Extortion, theft, and violent crime affect the legitimacy of the government and drastically complicate business operations in the country.

South Africa has one of the highest crime rates in the world and continues to see increases in violent crime, including crime that specifically targets businesses. New data put out by the government demonstrates that crime rates have increased since 2021 - coinciding with a decrease in government popularity throughout the same period. Compared to wealthy communities, crime rates in poorer neighbourhoods like Khayelitsha are nearly five times higher, which is indicative of country-wide trends. The significant economic and social issues that residents experience are linked to this disparity. According to research by the Institute for Security Studies, Khayelitsha's high unemployment rate, poor housing conditions, and restricted access to social services all lead to higher crime rates. These circumstances encourage grievances, which can lead people to commit crimes, as illustrated by strong empirical evidence linking economic hardship to higher crime rates in South Africa.

In addition to community-level crime, South Africa is plagued by transnational organised criminal networks that worsen the business environment, slow the economy, and threaten individuals' physical and financial security. According to the Organised Crime Index, South Africa ranks 3rd as the African country most affected by organized crime, based on the prevalence of criminal activity and the ineffectiveness of state responses to counteract it. Transnational organized crime is defined as illegal activities carried out across borders by structured networks such as gangs, drug trafficking syndicates and international criminal networks. The most prevalent criminal markets in South Africa are human trafficking, financial crimes and arms trafficking. Throughout 2024 the South African Police Service dismantled 30 illegal drug laboratories and seized over $18 million worth of illegal drugs.

The prevalence of organised crime is deeply rooted in corruption within government and police forces and is worsened by a lack of cooperation between institutions. Because a large number of politicians and bureaucrats benefit from corrupt relationships with criminal organizations, they hold a vested interest in impeding efforts to combat it. Government officials are frequently compensated to overlook illicit actions once they are uncovered and to provide details on police operations and strategies to combat criminal activities. Despite government strategies implemented to combat organised crime, a lack of institutional cooperation and corruption among government and police forces have hindered their efforts.

There are substantial geopolitical and economic implications of South Africa's internal instability and high crime rate. The country's failure to uphold internal security harms its standing as a regional and international leader, complicating its efforts to project influence and collaborate on international projects through its G20 presidency.

High crime rates - and high rates of extortion specifically - significantly discourage foreign investment; foreign investors have refrained from entering the South African market due to costs associated with crime, including security measures and insurance premiums. Furthermore, a World Bank study from 2023 on South Africa's investment climate notes that a decline in FDI has been observed in industries such as tourism and manufacturing due to safety concerns and high crime rates.

The South African government has attempted to implement several policies to lower crime rates. Crime reduction is a major goal of initiatives such as the National Development Plan (NDP) 2030. Strategies to achieve this goal focus on strengthening law enforcement, improving the justice system, and addressing the socioeconomic drivers of crime. These efforts are complemented by increased funding for the South African Police Service (SAPS) and the adoption of community policing techniques. Unfortunately, corruption, low funding, and the absence of institutional collaboration have frequently impeded these attempts. The overall influence on national crime levels has been minimal, notwithstanding localised successes in certain urban districts. A recent Gallup poll indicated that South Africa ranks among the top three countries in which people feel the least safe walking alone at night. This suggests that more comprehensive strategies are required that address the underlying socio-economic problems that drive crime, in addition to improving law enforcement capabilities.

Assessment:

We assess that insufficient investment in social development, coupled with the failure to address corruption linking the state to transnational criminal networks, is likely to exacerbate existing disparities between communities. This will likely place additional strain on the state’s resources, given the government’s inevitable investment in policing and short-term security expenditures. Rising crime rates driven by unrestrained poverty and inequality will likely fuel growing social unrest and continue to erode public trust in state institutions.

Pessimism concerning South Africa’s investment climate will likely continue to harm the government’s popularity and legitimacy. Limited economic growth worsens already-existing social inequalities, further inhibiting economic progress, and restricting the creation of new jobs. The risk of increasingly frequent and violent civil unrest will likely deter foreign companies from operating in the country, further restricting FDI flows and directly constraining economic growth.

We assess that heightened levels of social unrest are likely to compel the government to divert substantial resources toward security and reconstruction efforts, further constraining funding for investments targeting poverty, inequality, and unemployment. Effective investments targeting structural economic adjustments and socially focused projects will likely benefit the GNU’s expenditures in the long term.

Populism

Right and left-wing populism is on the rise in South Africa. The ANC dropped from a 70% vote share in 2004 to 40.2% in the 2024 general elections. In the same election, populist parties uMkhonto weSizwe (MK) and Economic Freedom Fighters (EFF) respectively gained 14.6% and 9.5% of the vote share.

The rise of populism in South Africa can in part be explained by high voter discontent for the longstanding ruling party, the ANC. Persistent economic challenges that disproportionately impact less educated and economically disadvantaged segments of the population are likely to continue to drive these groups to support populist parties.

Continued failure to address long-standing economic grievances by the government is likely to lead to the further delegitimization of the GNU, threatening its coalition and leading to increased support for populist parties.

Increases in support for populist parties can be particularly observed in rural areas, which have high levels of voter discontent due to regional economic disparities. Rural areas tend to suffer more economically. As of 2017, poverty rates in rural areas (81.3%) were about double those in urban areas (40.7%). Poverty in rural areas has been exacerbated by the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic, the national hunger crisis, as well as continuous load shedding.

For instance, the largely rural province of Kwazulu-Natal had the highest share of votes for populist parties of all provinces in the 2024 election. Zuma’s populist party MK received 45.3% of Kwazulu-Natal’s votes. Kwazulu-Natal also has the second-highest number of people living in poverty. In Gauteng - an urban, comparatively wealthy province that makes up roughly 33% of GDP and has the highest provincial GDP per capita - voters largely backed the ANC.

Simultaneously, lower voter turnout rates can be more broadly observed in provinces that have higher GDP per capita, with the exceptions of Gauteng and the Western Cape. Moreover, voter turnout in the 2024 elections reached a historic low of 58.6% (in comparison to 89.3% in 1999). This could be indicative of a wider trend in which voter fatigue has driven lower turnouts in ANC strongholds and stronger turnouts in regions where populist parties have wider support.

Assessment:

We assess populist parties are likely to continue to mobilise poorer segments of the population to cast protest votes against the perceived status quo. Additionally, growing disillusionment with the ANC-led coalition will likely lead to further increases in voter abstention among former ANC supporters, reflecting a deepening erosion of confidence in the government. This trend is underscored by the historically low voter turnout observed in the 2024 elections.

This trend is likely to be exacerbated by the rhetoric of populist parties, which particularly target poorer and predominantly ethnically black communities. In the long term, there is a reasonable possibility that this will result in a significant shift in vote distribution, further weakening the ANC and posing a threat to the GNU.

This trend is likely to persist in both future regional and national elections unless the GNU’s policies effectively address the needs of disenfranchised communities. Such measures must include structural economic reforms and effective investments in education, infrastructure, social programs, and poverty alleviation initiatives at the local level.

The Shift Towards Private Sector-led Growth in Rwanda

Home to some of the fastest economic expansion in the world over the last 20 years, Rwanda has achieved an annual average GDP growth rate of 7% over the last two decades. Paul Kagame, who has served as the country’s president since 2000, is broadly considered by analysts and observers both domestically and internationally as the engineer of Rwanda’s notable economic transformation following the end of the genocide in 1994.

On the demand side, economic growth over the last two decades has been the result of a large public expenditure. Notwithstanding the positive economic transformation this has engendered, it has resulted in several structural challenges for the government. Rwanda’s public-sector-led development model has led to considerable fiscal deficits primarily financed through external borrowing. Debt has risen from 15.6% of GDP in 2012 to 48.9% in 2022. Whilst the national poverty rate declined from 75.2% to 53.5% from 2000 to 2013, this trend has stagnated since, with 56.5% of the population living on less than $1.90 a day.

Capitalising on the opportunities presented by Rwanda’s relatively undeveloped private sector would help to remedy the country’s current economic challenges, and create opportunities for overseas investors and companies.

Advocacy for private sector-led growth from policy makers

Key policy documents published over the past years and months illustrate the importance the Rwandan government attaches to private sector development to create future economic growth. Engaging the private sector and diversifying sources of finances features as one of the four strategic objectives of the country’s ‘National Investment Policy’ (NIP) published in December 2020 by the Ministry of Finance and Economic Planning. The private sector-led economy envisaged by the NIP is one underpinned by increasing mixed funding through mechanisms such as public-private partnerships (PPPs) and joint ventures (JVs), as well as facilitating export-led growth to improve the country’s balance of payments position and increase foreign exchange earnings. The NIP outlines that whilst PPPs have traditionally been a rare form of financing they are “a suitable step to attract further domestic and foreign investors by efficiently sharing inherent project risks and thereby making investing in the provision of public goods and services more attractive for private partners”.

Equally, Kagame’s flagship national development strategy Rwanda Vision 2050, which was launched by Kagame in 2020, highlights the importance of continuing “the journey towards self-reliance through a private sector-led growth”. As is outlined in the Vision 2050 blueprint, leveraging the country’s demographic dividend, increasing the value of human capital by strengthening the country’s education system, and creating “new growth poles” through urbanisation will serve to increase competitiveness and facilitate the operations of private companies. More recently, Rwanda’s proposed budget for the fiscal year 2024-25, serves as an indicator that the government will opt for a state-driven and proactive approach to encouraging foreign investment during Kagame’s fourth term. As outlined in the proposed budget, the government intends to increase public spending by 11.2% during the fiscal year, with RWF 2,037.4 billion (approximately USD 15.5 billion) to be allocated for both foreign and domestically financed projects.

Structural challenges undermining private sector development

Despite increasing awareness amongst policymakers of the importance of driving private sector growth, they face several structural barriers to achieving this goal.

Rwanda is confronted with a deficit of skilled workers upon which the government’s vision of private sector growth spurred by innovation and a prospering services sector is contingent upon. The country’s labour market remains characterised by low-skilled, low wage and informal work, with 85% of workers being informally employed as of 2021. Whilst Rwanda’s agriculture sector only makes up 27% of the country’s GDP, it employs 72.2% of the population, primarily in low-skilled and informal positions. Professions such as accountants, lawyers and engineers, on the other hand, are in particular shortfall. Rwanda’s educational framework is in part accountable for the current state of the workforce, with enrolment in tertiary education at 8% for men and 7% for women in 2023. Without access to higher education and specialised training opportunities, workers will be unable to fill the technical and managerial positions that private investment, especially in areas such as services, is dependent on. Investment into the service sector is of particular importance. As Rwanda lacks the natural resources of some of its neighbours, the tertiary sector will underpin future economic growth.

Access to financing solutions and affordable credit constitutes a further obstacle to private sector development. Lending rates are amongst the highest in the region not dipping below 14.16% in the last two decades and banks primarily offer short-term loans with collateral requirements regularly higher than 100% of the loan value. Viable equity financing solutions remain limited for micro, small and medium-sized enterprises (SMMEs). The Rwanda Stock Exchange remains nascent and only constitutes an equity solution for a handful of large companies. Whilst foreign private investors and companies can overcome these issues by leveraging external sources of financing, domestic companies are not presented with the same options, with local SMMEs often lacking the low-cost financing solutions to unlock growth at the early stages of a company’s development.

Advancing towards a private sector-led economy

There are grounds to believe that Rwanda will be successful in its transition towards a private sector-led economy. Firstly, the transition is already underway. Under Vision 2020, which ran from 2000-2020, a host of reforms were implemented to unlock private investment such as privatisation of state-owned companies and introduction of tax incentives. Between 1996 and 2017, 56 formerly state-owned companies were privatised. Large companies that the Government of Rwanda has sold its stake in through the Rwanda Stock Exchange include: MTN Rwanda - the country’s largest telecommunications company, which was first listed on the RSE in May 2021 - and the Bank of Kigali, which the government sold its 20% stake in through the company’s Initial Public Offering (IPO) in September 2011. Moreover, in February 2021, Rwanda’s Investment Code, which seeks to promote and facilitate investment in Rwanda, was enacted into law. The legislation introduced a wide array of investment incentives, including a preferential corporate tax income rate of 0% offered to any international company that establishes its headquarters and regional offices in Rwanda; invests the equivalent of USD $10 million in the company in tangible and intangible assets; and provides employment and training to Rwandans, amongst other conditions.

Secondly, Rwanda offers foreign and local companies a favourable regulatory environment and a relatively low and declining levels of corruption and crime. In 2020, Rwanda ranked second highest in Africa on the World Bank’s Ease of Doing Business index, jumping 100 places in two decades. The index ranks countries on how conducive their regulatory environments are for establishing and operating a firm in country. Countries are ranked on several topics including starting a business, registering a property and enforcing contracts. Corruption and crime are also in decline in Rwanda, with the country receiving the lowest score in East Africa on Transparency International’s Corruption Perceptions Index in 2023 and being the second safest country on the continent according to the ENACT Organised Crime Index 2023.

The top-down policy and decision-making structures established by the government have also traditionally shown themselves to facilitate the implementation of economic reforms. International commentators have noted that Western countries provide Rwanda with more aid than other African countries because they deem the country to use it more effectively. These frameworks will likely remain broadly unchanged with Kagame set for at least another five years in office. And we assess that future policies to boost private sector growth will likely be implemented with a similar efficacy. Kagame has committed to improving the economic security of Rwandans and has pledged to transform Rwanda into an upper-middle country before the end of his next term. With 37% of the country’s population under the age 15, Rwanda’s youth will become a powerful voice in the years to come. They represent a valuable driver of growth, however, in the absence of private sector development and integration, they are not likely to be better off than the generations that preceded them.

Despite Rwanda’s traditional reliance on public funds for stimulating economic growth, Kagame has remained persistent in his desire to attract private investment. In recent years, his administration has sought to implement policies, which breaking with the past, are likely to unlock private sector growth. Coupled with high and sustained levels of growth and other progress made under Vision 2020, such as infrastructure developments, a more central role for the private sector within Rwanda’s growth strategy will likely present untapped opportunities for overseas investors and businesses in the years to come, particularly in Rwanda’s fastest growing tertiary sectors such as financial services, IT and hospitality.

Hunger Crisis in the Democratic Republic of the Congo

Overview

The Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) is currently experiencing one of the world’s worst hunger crises, with 42.5 million people, of the country’s total population of 105.9 million, experiencing insufficient food consumption. Of these, approximately 23.4 million people are acutely food insecure, including an estimated 4.5 million children who are acutely malnourished. The resurgence of armed conflict in the eastern provinces of Ituri, North Kivu, and South Kivu since 2022 has further exacerbated the situation, with 7.3 million people currently displaced across the country. Women and children are bearing the brunt of the crisis, with access to food and other critical resources severely limited and incidences of sexual harassment, exploitation, and abuse surging in the affected areas.

Drivers and Causes

The hunger crisis in the DRC is fuelled by a myriad of factors, including environmental disasters, conflict, economic instability, and poor governance. Although the country possesses significant natural resources such as copper, cobalt, diamonds, and tin, the Congolese population does not benefit from the country’s natural wealth. The DRC is one of the poorest countries in the world, with a score of 0.481 on the 2022 UNDP Human Development Index (HDI), placing it 180th out of 193 countries. Poverty is widespread, with an estimated 74.6 per cent of the population living on less than $2.15 a day in 2023, and much of the population struggles to access basic necessities such as electricity and safe and reliable drinking water.

One of the key factors driving hunger in the DRC is the occurrence of frequent natural disasters such as floods, drought, volcanic activity, and epidemics. In 2021, the eruption of Mount Nyiragongo forced at least 232,000 people to flee their homes in Goma and the surrounding areas as lava flows destroyed more than 3,500 houses and toxic volcanic gases threatened both people’s lives and the environment. Similarly, the flooding of the Congo River in January 2024 affected more than 1,8 million people, destroying thousands of houses, farmland, and critical infrastructure, such as health care, water, and sanitation facilities. While the DRC’s geographical location in the Congo Basin makes it prone to climate hazards, climate change is increasing the frequency and severity of extreme weather events in the country, with floods, droughts, and heat waves all expected to increase over the coming decades.

Alongside disasters, violent conflict is another significant cause of hunger in the DRC. Since gaining independence from Belgium in 1960, the DRC has experienced persistent conflict with political tensions and rivalries over natural resources fuelling violence between different national and ethnic groups. In 1996, Rwandan forces invaded the DRC (then known as Zaire) to root out Hutu rebel groups that had taken cover in the eastern parts of the country, leading to a regional war that pitted Rwanda and its allies along with foreign and domestic rebel groups against the Congolese government of Joseph Mobutu. In 1997, Mobutu was overthrown and replaced by the rebels’ political leader Laurent Kabila. Yet, tensions between Kabila and his allies, Rwanda and Uganda, soon began to mount, resulting in the Second Congo War of 1998. While the war officially ended in 2003, ethnic tensions persisted and continue to be a significant obstacle to long-term peace and development to this day. In 2022, violence escalated between the DRC’s armed forces (FARDC) and the Rwanda-backed M23 Tutsi-led rebels in the eastern DRC, resulting in the killing of several thousand civilians and the forcible displacement of hundreds of thousands more across the region. While exact data on the number of victims is difficult to ascertain, the United Nations estimates that, since 1996, approximately 6 million people have died as a result of war in the eastern DRC, making the conflict the deadliest event since World War II.

Impact

Almost thirty years of conflict, environmental disasters, and poor governance have created a humanitarian crisis of immense proportions in the DRC. The 2024 Global Hunger Index ranks the DRC 123rd out of 127 countries based on indicators of undernutrition, child stunting, child wasting, and child mortality and rates the country’s food security situation as ‘serious’. Hunger is pervasive all across the country and the prevalence of insufficient food consumption is generally high or very high, with 22 of the DRC’s 26 provinces currently experiencing food insecurity levels at or above 30 per cent. This includes the provinces of North Kivu (4,2 million), South Kivu (3,7 million), Ituri (3,2 million), Kasaï-Central (2,9 million), Kinshasa (2,8 million), Kasaï (2,5 million), and Kasaï-Oriental (2,3 million), which together hold more than half of the DRC’s food-insecure population.

While food insecurity affects all segments of Congolese society, women and children have been particularly hard hit by the crisis and face a range of protection issues. In 2023, an estimated 2.8 million children under 5 years old and an estimated 2.2 million pregnant and breastfeeding women were acutely malnourished, with women and children in the conflict-torn provinces of Ituri, North Kivu, and South Kivu the most affected. Malnutrition-related effects include weakened immunity to disease and infections, increased risk of pregnancy and childbirth complications, and stunted growth and developmental delays in children. In the DRC, child stunting is especially common, with 36 per cent of children under five estimated to be affected in 2024. The child wasting rate, while comparatively lower at an estimated 6.6 per cent, is also high, as is the child mortality rate, which at an estimated 7.6 per cent is almost three times the world’s average of 2.6 per cent.

Besides the immediate risk to health and wellbeing, food insecurity makes women and children susceptible to a number of secondary threats, including sexual and gender-based violence, exploitation, and abuse. With food in short supply, many Congolese women and girls are forced to exchange sex for food and water for themselves and their families, while others have to enter forced or arranged marriages to survive. Attacks on water and food-seeking women and girls are also frequent, with those uprooted by violence and conflict the most at risk. In the conflict-affected areas of the eastern DRC, incidences of physical and sexual violence against women and children are particularly high. With no safe shelter available, women and children in the displacement camps in Ituri, North Kivu, and South Kivu are exposed to heightened risks of rape and abduction, while child recruitment by armed groups is also common. Although no exact data on the number of sexual offence and child recruitment victims exists, in 2022 over 80,000 cases of gender-based violence were reported in the DRC while at least 1,545 children were recruited and used by armed groups. The true number of victims, however, is likely to be far higher.

Recommendations and Implications

Relief efforts so far have focused on providing emergency food assistance, health care, and livelihood support to vulnerable populations and communities within the DRC and surrounding areas. In 2023, 6.9 million people out of a target of 10 million people were reached, but a lack of funding limits humanitarian actors’ response capacity. In 2023, the humanitarian funding gap for the DRC reached a record $1,311,860, or 58 per cent of the total budget required, with the figure for 2024 currently standing at 55 per cent. Additional help is especially needed in the eastern DRC, where a new clade of mpox is rapidly spreading and threatening the already precarious existence of people living in refugee camps. However, to carry out their work effectively and reach a greater number of people, humanitarian actors require greater financial assistance, both from donor governments and private contributions.

For those operating on the ground, personal safety has become a growing concern in recent years. In 2023, more than 217 security incidents involving humanitarian workers were recorded in the DRC, including almost 30 abductions, around 20 injuries, and at least 3 deaths. Since the beginning of 2024, this number has further increased, with more than 170 attacks on humanitarian workers reported in the first six months of the year alone. Most attacks are taking place in the eastern provinces of Ituri, North Kivu, and South Kivu, where fighting between government and armed opposition forces continues to rage despite the conclusion of a ceasefire agreement on July 30, 2024.

In North Kivu, the security situation is particularly challenging. Since the beginning of the year, M23 forces have significantly expanded the territory under their control, most recently, in early August 2024, capturing the towns of Ishasha, Katwiguru, Kisharo, Nyamilima, and Nyakakoma and taking control of the southern and eastern shores of Lake Edouard and areas along the Ugandan border. Fighting between the M23, FARDC, and pro-government Wazalendo militias has also been reported in the Lubero and Rutshuru territories in recent weeks, killing at least 16 people. In Ituri, armed groups including the Islamic State-affiliated Allied Democratic Forces (ADF) and the Cooperative for the Development of Congo (CODECO) remain active, launching recurrent attacks against civilians in the territories of Djugo, Irumu, and Mambasa. In South Kivu, the withdrawal of the United Nations Organisation Stabilisation Mission (MONUSCO) in June 2024 has raised concerns about a potential security vacuum, especially given the M23’s recent advance into the region. In light of the rapidly changing security landscape, it is therefore vital that humanitarian organisations liaise with local stakeholders and secure timely insights on armed group activities and movements. If your organisation is interested in tailored, PRO BONO insights from London Politica’s Africa Desk, please contact us at externalrelations@londonpolitica.com.

Burkina Faso Geopolitical Risk Assessment

Introduction

Burkina Faso (BF) is currently ruled by a military junta under the leadership of Captain Ibrahim Traoré, who came to power through a coup in September 2022. Since the takeover, the junta has adopted an increasingly militaristic and authoritarian approach, while steering BF away from alliances with Western powers, in favour of states such as Russia, who have promised the government heavy military support. Next to strengthening the junta's position, combating powerful non-state armed groups (NSAGs) is the main political driver in BF.

NSAGs mostly include Islamist terror organisations, including home-grown extremist groups and jihadist fighters from neighbouring countries. Many NSAGs operating in the country are linked to larger organisations such as al-Qaeda and the Islamic State (ISIS). Due to their ability to move across BF’s neighbours' porous borders and their desire to attack civilians, NGOs, security forces and infrastructure, they pose a serious domestic as well as regional risk, and are likely to continue to do so over the short to medium term. The lacklustre performance of previous governments and allies in their efforts to improve the security situation in BF has precipitated two coups in as many years, the expulsion of French and other Western forces, the ejection of UN personnel, and an open invitation to the Kremlin.

Executive Summary:

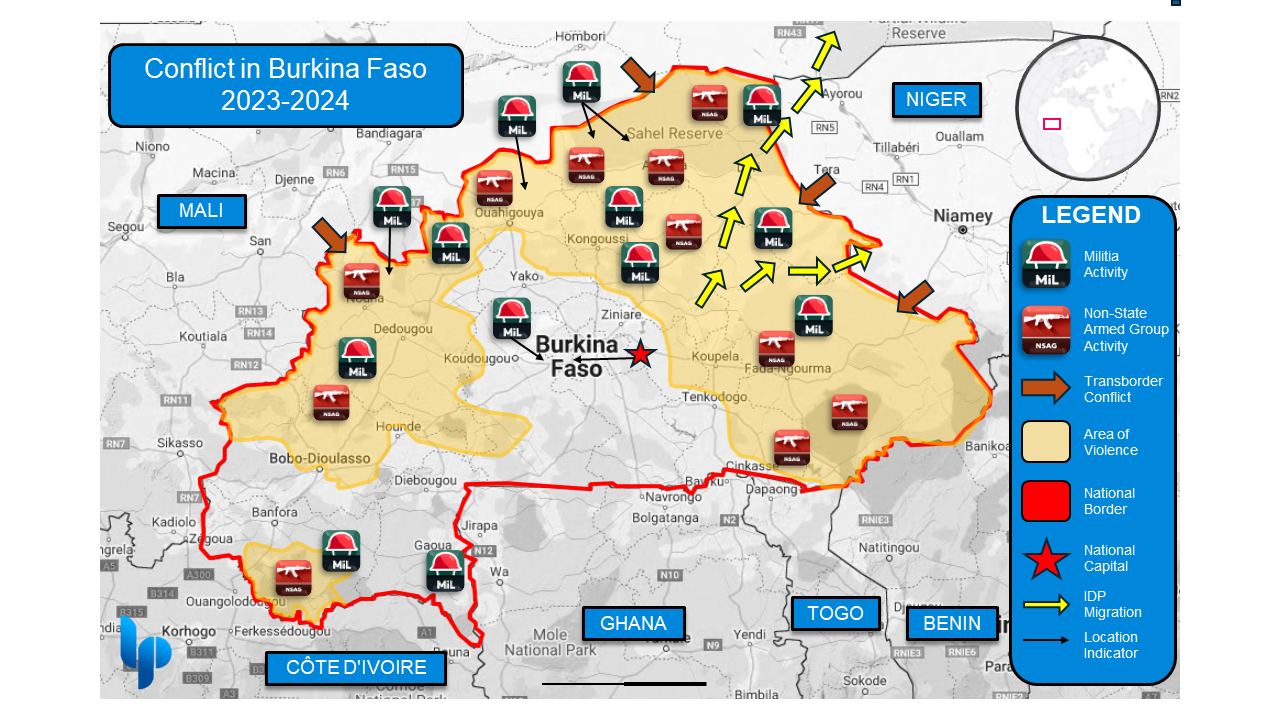

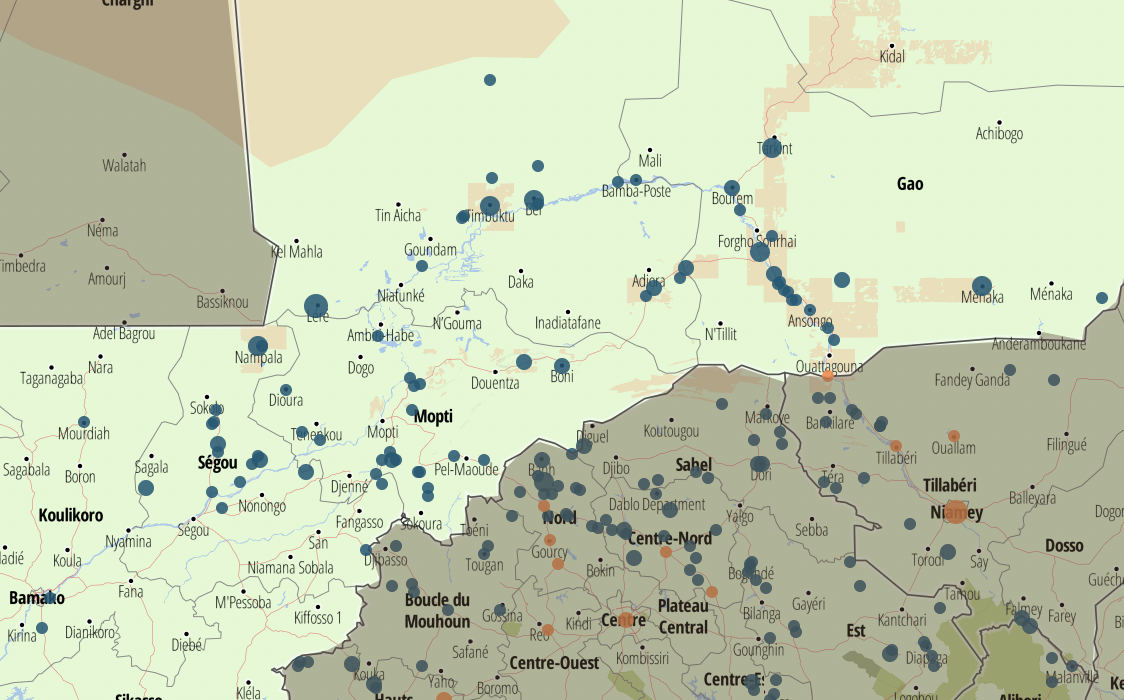

The ongoing conflict between security forces, terror groups, local militias, and external forces will very likely pose a very high risk to civilians and foreigners across the country over at least the next year, apart from central regions in immediate proximity to Ougadougu (as per Figure 1).

Harassment and violence against foreign nationals (particularly French citizens) is likely due to strong anti-Western sentiment fuelled by disinformation campaigns. NGOs and aid workers face significant risks from both NSAGs and government-linked security forces, leading to a challenging operational environment.

We assess with moderate confidence that while GDP growth will remain stable over the next 8-12 months, it will fall short of the previous years' expectations and lag behind regional partners like the Ivory Coast. Political instability, security issues, macro tail risk, and climate factors present significant challenges for individual foreign investors.

Political Risk

The number of Burkinabé civilians and soldiers killed by extremists has risen sharply over the past five years and continues to increase under Traoré’s leadership;

Despite this, public support remains high amid disinformation campaigns which label the French, UN, and ECOWAS, as corrupt entities;

Levels of corruption within government and industry are pervasive;

Russia acts as a key strategic partner to the military junta, rivalled by Turkey; and,

A formalised Confederation of Sahelian States strengthens Traoré’s government, but would very likely impact regional economics and thus global businesses and organisations, through liquidity, trade, security, and movement difficulties.

BF has experienced recurring military coups attempts over the last ten years (2014, 2015, 2022). The present government, under Captain Ibrahim Traoré, came into power in 2022 on an anti-colonial platform, as well as on the premise that the previous governments were incapable of handling the jihadist threat. On foreign policy, Traoré has taken a similar approach to BF's neighbours Mali and Niger; distancing themselves from Western states and institutions such as the UN, as well as severing ties with former colonial power France. The overall region’s influence on anti-France and pro-Russian narratives was apparent in the lead-up to BF’s 2022 coup and has created space that Russia continues to exploit via soft and hard power. In April this year, Burkinabé authorities expelled several French diplomats, after having previously ejected the ambassador and defence attaché. French nationals, businesspeople, and aid workers have also occasionally been detained, in some cases charged with espionage and subsequently deported.

Russia continues to play a strong domestic role; utilising propaganda, deploying fake social media accounts, fake news sites, and state controlled mass-media centres to conduct disinformation campaigns that have led to democratic backsliding. Russia also employs military aid to fill holes left by France and the UN in BF’s fight against jihadism. Indeed, the Kremlin has made itself an indispensable partner of the Traoré government and plays a significant role in the buttressing of broad domestic support for the junta.

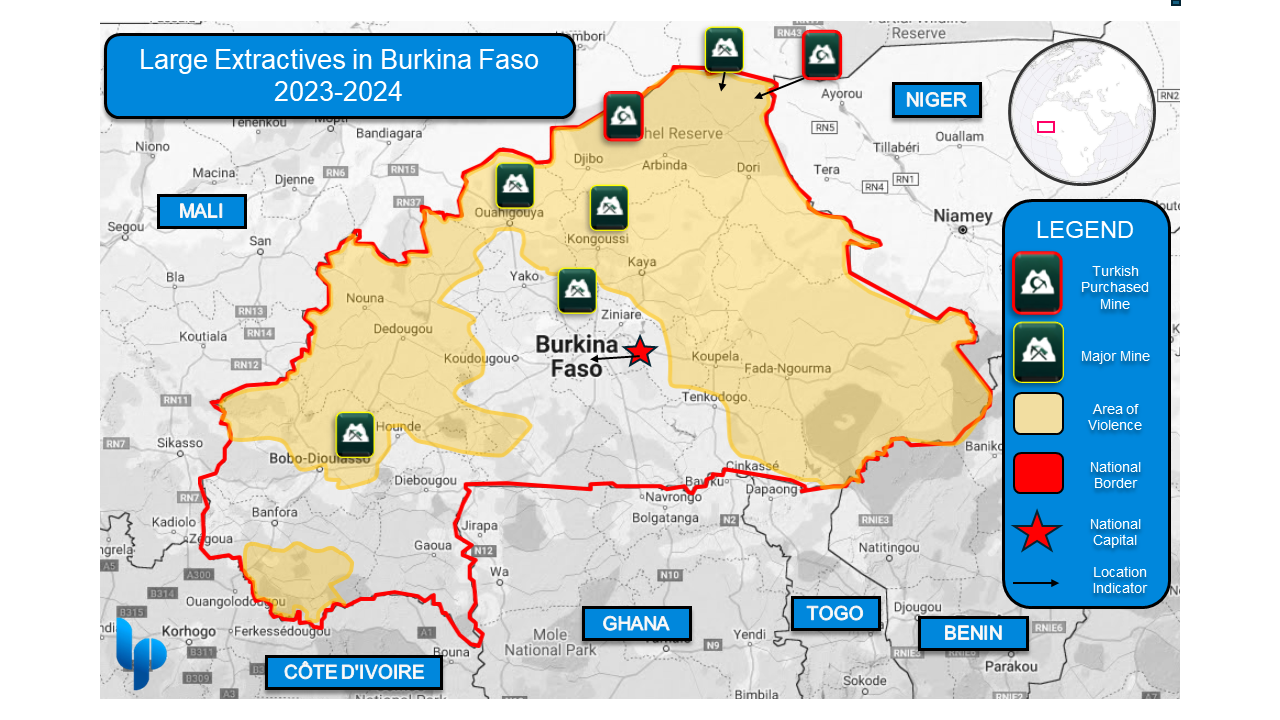

Turkey also works to maintain economic, religious, educational, industrial, and military ties with BF, making President Erdoğan a key regional player with significant soft power. The two nations hold several joint commissions and agency corporations, which facilitate the transfer of Turkish development aid, student exchanges, and the sale of significant military equipment – such as the Turkish TB2, a medium altitude, long endurance, ISR and attack drone that has been linked to several human rights violations in BF.

The ‘transitional’ government under Captain Traoré has so far signalled little interest in shifting the country towards democratic rule. In September 2023, the junta cancelled elections scheduled for July 2024, and postponed them indefinitely, labelling them “not a priority”. Governing power remains bundled centrally in the putschist executive, after elected and other transitional bodies were dissolved post-coup.

We assess that public support for Traoré's government remains high, at least in the capital and surrounding regions, with no signs of major unrest/dissidence over the last six months. However, political indicators, such as message control and quickly deployed counter-factual narratives, suggest that the government's popularity can, to a significant extent, be attributed to Russian disinformation campaigns. Traoré’s stability is also maintained through a propagandist civil-political organisation known as the Wayiyans. Acting largely as a watchdog, the organisation is active in a range of activities, from political rallies to vigilante ‘stability’ patrols around the capital. Traoré has effectively dulled any major internal political opposition.

Reporting around a lone gunman attack at the presidential palace in Ouagadougou further demonstrates the depth and sophistication of information-operations within Burkina Faso. The incident in question does not have any obvious political connection, however, local news and social media quickly framed it as a failed coup attempt, spinning a narrative of demonstrated regime strength.

Anti-government demonstrations, which have declined significantly since Traoré’s coup, were frequently centred around anti-French sentiment. Since the recent departure of French troops, they have largely died down. Even though the population appears pro-government, increased reporting around human rights violations perpetrated by local militias, the expulsion of certain news outlets, and a decrease in civil liberties might increasingly fuel disenchantment among the population.

Regional observers have reported on isolated incidents of internal dissent, such as the formation of the political group FDR (The Front for the Defence of the Republic) in early April 2024. The organisation's spokesperson, Inoussa Ouédraogo, called for the “immediate release of all those forcibly conscripted, kidnapped or sequestered by the militias under the orders of Ibrahim Traoré.” However, as of today, the lack of civil unrest and protests suggests that opposition movements have not managed to gain significant momentum. This could change if the junta is not able to produce results against NSAGs over the next 12-24 months, as failure to address the jihadist threat has been a driving factor in past transitions of power.

Since Traoré’s coup, the junta has also been pursuing closer cooperation with the military governments of Niger and Mali. During a recent summit in the beginning of July, the neighbours announced the formalisation of a Confederation of Sahel States (AES). The alliance strengthens the position of Traoré and his colleagues, while further isolating them from the regional Economic Communities of Western African States (ECOWAS) block. The AES’s main goal is increased security cooperation but it also seeks to improve economic ties. For instance, the three leaders have set their sights on a common currency, in an attempt to move away from the French-backed CFA Franc used by many states in West Africa. This development would strongly disrupt trade stability between BF and its key trading partners, such as Cote d'Ivoire.

BF has historically struggled with corruption at the federal and municipal level. Anti-corruption protests are a recurring pattern - the most recent broke out just last year. Local authorities are commonly engaged in bribery, extortion, and rent-seeking. The commodities sector is particularly affected. Mining firms often cooperate with corrupt local authorities to attain commercial licensing or exploitation rights, leading to extensive compliance and reputational risks. Captain Traoré has paid lip-service to an increased fight against corruption with high profile arrests, but the efforts have not been far-reaching and do not reflect tangible changes. While corruption remains common, it has not increased dramatically since 2016.

Pervasive corruption causes various negative externalities for foreign investors and international firms. For instance, involvement of local branches in bribery schemes exposes multinationals to reputational and even legal risks, while refusal to participate may result in additional commercial challenges, such as difficulties in getting permits etc. Overall, corruption is a major obstacle to Foreign Direct Investment (FDI), and stunts domestic economic development.

Assessment:

London Politica assesses the overall political risk level in Burkina Faso as high due to Burkina Faso’s vulnerability to government collapse, or state violence, given the country’s long history of forceful transfers of power. High levels of political risk associated with political instability and regime change pose a significant risk to entities that rely on policy continuity, including foreign companies that hold public contracts with the current government.

We assess as likely that the competition between Russia and Turkey will increase over the next 6-12 months, manifesting in a range of sectors, including industry, security, defence, and information. Global tensions between NATO and Russia may play a larger role in the region as a result. Firms from either block may face additional pressures when geopolitical frictions spill over into the investment sphere. Indeed, actors on both sides seek to use government access to consolidate their economic influence. The same could be true for NGOs, who may be perceived as foreign government entities and therefore are at risk of mistrust and discrimination by local authorities.

Further, we assess that over the next 6-12 months foreign nationals, particularly French citizens, are at a high risk of harassment or violence by local populations or extortion by government representatives. This endangers business continuity in the country and negatively affects the investment outlook for lenders as well as capital allocators, leading to a more complex and challenging commercial environment for foreign actors.

Security Risk

Terrorism is at an all-time high in Burkina Faso, with over 2,000 fatalities and 1,312 civilian casualties in 2023;

Civilian casualties often occur in any area where NSAG (Non-State Actor Groups), government forces, or the Volunteers For the Defence of the Homeland militia (VDP) are operating;

Ongoing information operations have a significant effect on the disposition of government forces, especially the VDP militias who are a poorly trained and unprofessional force;

NGOs and foreign nationals have experienced discrimination and violence by both NSAGs and government security forces.

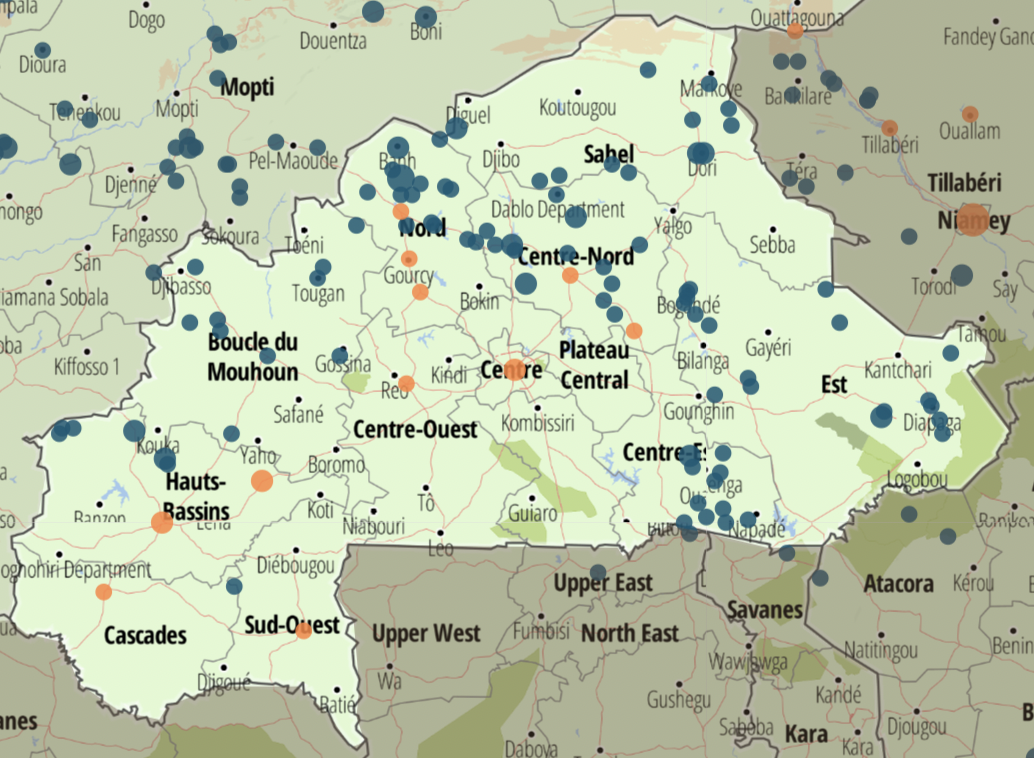

BF’s security situation has deteriorated since 2023, as security forces, including local militias, are ramping up their presence and operations in NSAG controlled territory. The Figure below provides an overview of the conflict, highlighting areas of reported militia and NSAG activity that has resulted in casualties or collateral damage. London Politica’s research supports an assessment by ECOWAS, which highlights that Burkina Faso’s government controls less than 60% of the country.

NSAGs and Terrorism

BF currently experiences the highest frequency of terror attacks globally. In 2023 alone, around 2,000 people were killed in terror related incidents. In fact, over a quarter of the world’s terror related deaths occurred in the country in that same period. Notable incidents in 2023 included the killing of 71 soldiers in the province of l’Oudalan by an IS Sahel faction and the murder of 61 civilians in Partiaga, a village in the Tapoa province, by Jama’at Nusrat al-Islam wal-Muslimin (JNIM). [see London Politica Sahelian Security Assessment for JNIM profile] JNIM remains the dominant terror organisation in the country. More recent examples include an attack in February 2024, in which terrorists targeted a Catholic church in the north-east, killing 15 worshippers. On the same day, militants massacred several dozen civilians in a mosque in the south-eastern city of Natiaboani. These incidences were reported over X by local journalists.

Insurgent guerrilla strategy - including ambushes and hit-and-run tactics - are prevalent in BF. JNIM, for instance, conducts both sophisticated and simple IED attacks to create disruption and tunnel targets into favourable attack positions. Both JNIM and other NSAGs engage in kidnappings to extract ransom payments and organised intimidation tactics to levy taxes on local businesses and NGOs in their territories. Human and arms trafficking is also pervasive in militant controlled regions. NSAGs are also leveraging access to the illegal gold trade and sale of looted government or NGO supplies, to finance their operations. JNIM, for instance, has been aggressively trying to expand their grip on lucrative mining regions, where they mine and smuggle gold, but also provide paid security for locals engaged in artisanal mining.

Terror attacks continue to occur across the country, with a particularly high frequency near the Malian border and the tri-border region between Burkina Faso, Niger and Mali, where militants take advantage of weak border security. The centre of the country, particularly in close proximity to the capital, has been comparatively safe.

Government Security Forces & Vigilante Militias

International observers have also accused government security forces of violence against civilians. Human Rights Watch (HRW) recently published a report accusing the army of killing 223 villagers in February, near the northern border to Mali. HRW has highlighted numerous civilian casualties resulting from TB2 drone strikes, in both 2023 and 2024. Militias have also been accused of atrocities. Reports indicate that the Volunteers for the Defense of the Fatherland (VDP), a national militia created by the Burkinabe government, massacred 156 people in the northern village Karma in April 2024. Their attacks, which have also included forced disappearances and summary executions, often target ethnic Fulanis, who are perceived as extremists by factions of the militia.

The VDP has a strong presence on the front-line against NSAGs, often suffering heavy casualties. The militia relies on quick recruitment and poor training to ensure rapid deployment. While VDP personnel have benefitted from a recent 30% pay rise, the group has also been implicated in criminality, including extortion and kidnappings. As the VDP recruitment numbers have grown, so has NSAG retaliation against communities linked to the militia. IDP camps, perceived as VDP loyal, have suffered reprisal from groups, including from al Qaida-affiliated organisations.

Sporadic social media reporting also suggests a decrease in the recapture of territory, with an increase in permanent army checkpoints on key roads, enacted curfews and declared states of emergency in the most affected northern provinces.

NGO staff, in particular those operating in contested regions, also face increasing harassment and violence from both NSAGs and security forces, including the VDP. Amnesty International reports high-levels of mistrust against NGO members amongst locals and the military alike, who sometimes suspect aid workers of supporting jihadist organisations. These attitudes are boosted by the spread of disinformation. Attacks on NGO staff have ranged from discrimination and wrongful detention to beatings and murder. NSAGs also frequently loot aid convoys. We assess that these risks will not abate over the next 12-months and NGOs operating in conflict zones, particularly around internally displaced persons in the north and northeastern provinces, will have to continuously monitor their security exposure to both government troops and NSAGs.

External Forces

Reporting on the specific activities of the Kremlin-backed Africa Korps remains sparse. The unit, which was established after the disbandment of the Wagner Group, employs mercenaries (including former Wagner members) as well as volunteers, and operates under the umbrella of the Russian defence ministry. While the Russian paramilitaries were originally brought in under the guise of filling the French anti-terror gap, regional sources indicate that their main mandate is to protect the military government, enabling the junta’s political aspirations while carrying out targeted missions and training Burkinabé forces. The organisation continues to recruit heavily across the Russian-speaking world, but has also signalled the desire to expand their ranks locally, in BF. The group has been linked to civilian deaths in neighbouring countries, but continues to enjoy a strong backing by BF’s central government.

Assessement:

London Politica assesses that continued, widespread violence between NSAGs and security forces are highly likely over the next 12 months. It is unlikely that the security situation in the non-capital regions will improve, as government forces have not been able to effectively combat NSAGs in contested regions causing violent spillovers affecting civilians.

We assess that the targeting and harassment of NGOs and foreign nationals by security forces will remain highly likely over the next 12 months. Travellers are advised to avoid known areas of conflict, including the northern border regions of Soum, Oudalan, and Seno. Additionally, travellers should limit travel to main service routes around the capital-south regions around Ganzourgou, Boulgou, Naouri and Bazega. Professionals and aid workers are also advised to hire armed escorts ahead of travel and have emergency backup routes prepared. Staff deployed to conflict regions are exposed to the risk of violent attacks, looting of supplies, and kidnappings by terror organisations. They are also at risk of harassment, detention, torture, and murder from government troops, particularly in regions in which the VDP operates - such as Seno, Kossi, Tapoa, Bam, and Yatenga.

Economic Risk

Burkina Faso's economy is projected to grow by 5.5% in 2024, driven by gold, manganese, cotton, and agricultural production. However, political instability and security issues, particularly attacks on industrial centres, pose significant risks to economic development.

Inflation has slowed due to stable commodity prices and monetary policy, but the macro environment remains volatile.

Turkey's FDI ambitions faced setbacks with revoked mining licences, while disputes among foreign investors highlight the challenging business environment.

Burkina Faso’s economy is driven by the production of gold, manganese, cotton and agricultural goods. The IMF has projected that the country’s economy will grow by 5.5%, slightly lower than the average of 6% from 2017-2019. The lagging economic performance is largely attributed to the precarious security situation and political instability.

Inflation, previously a grave concern to policy makers, has slowed down, mainly due to stabilising commodity prices and a monetary tightening of the Central Bank of West African States. The macro environment remains challenging, however, and resurging inflationary headwinds cannot be discounted over the next 12-months.

Overall, the country’s economic outlook hinges largely on the political and security situation. Indeed, many of the major industrial centres are located within contested regions and are prone to attacks by NSAGs. Extractives businesses are at particularly high risk. Additional headwinds will likely include climate events, such as reduced rainfall or drought, damaging agricultural yields. Presently, growth appears largely stable, positioning BF’s economy on solid footing, compared to regional standards.

A notable development in terms of FDI is the increasing influence of Turkey. Besides the sale of military equipment, Turkish firms are expanding into other business areas. The mining venture Afro Türk, for instance, purchased licences for the Tambao manganese mine and the Inata gold mine for $50 million in April 2023. However, in late March 2024 the operating licences were revoked again, due to failure to deliver full payment. The licences have since been handed over to new undisclosed investors. This set-back was a blow to Turkey’s ambitions and their relationship with the government. The now-defunct contract between the junta and the Turkish miner contained a noteworthy clause, which required the company to build security infrastructure for military forces fighting the NSAG threat in the vicinity of the mines, which is demonstrative of the pervasive threat these groups pose in the north of the country. This is also an indication of a broader, unspoken, trend; investors need to demonstrate alignment with the central government in order to win business, at least in major state-backed industries. Hence, this adds to the considerations of foreign business ventures, who might be wary of cozying up to an authoritarian government.

A recent dispute between Lilium Mining, the largest gold-producer in West Africa, and Endeavour Mining, a Canadian conglomerate, further demonstrates the challenging business environment in BF’s conflict zones. During the summer of 2023, Endeavour finalised a deal to sell their Boungou and Wahgnion mines to Lilium, due to the constant threat of attacks by terror organisations. The $300 million deal has since turned sour, as Endeavour brought forth a lawsuit, accusing its counterparty of failing to pay the agreed sum in full. Lilium in turn has launched legal proceedings against Endeavour, claiming they were misled regarding the operational capacities of the mines. Hence, the precarious security landscape poses serious challenges for foreign investors, especially regarding business continuity, but also when it comes to appraising investment opportunities, including the pricing of counterparty-risk.

Assessment:

BF’s economic landscape presents a high-risk environment for foreign firms considering launching or expanding business operations. The interplay of political instability, the presence of armed groups, geopolitical tensions, and other macro drivers creates significant challenges for investors. A high risk appetite is required.

We assess that the country’s economy is heavily reliant on commodity prices (cotton, gold). This dependency makes the macroeconomic environment highly volatile. Foreign firms must be prepared (hedges etc.) for significant fluctuations in revenue linked to global commodity markets.

It is highly likely that climate change exacerbates the frequency and severity of adverse weather events, presenting ongoing risks to economic stability and individual business operations. While extreme tail risk events such as the insect infestations that decimated cotton production in 2022 are unlikely, they remain a present risk that can have significant localised and macroeconomic impacts.

Political instability remains highly likely over the next year and a change in sentiment or government may bring about nationalisation of foreign-owned assets. International firms must navigate the political landscape cautiously, nurture good relationships with local and federal government, and develop contingency plans to mitigate the risk of abrupt policy changes.

The country hosts a high number of IDPs, resulting in a weakened workforce, leading to difficulties for foreign businesses seeking reliable labour. Companies must consider strategies to address potential labour shortages and invest in workforce development.

Infrastructure Risk

Infrastructure remains unreliable both due to underdevelopment and damage as a result of ongoing conflict;

Access to water and medical supplies are limited outside the capital, and competition over basic resources may lead to conflict

NGOs and commercial enterprises are likely to face difficulties traversing outside of the national capital region as a result of poor telecommunications and road infrastructure.

The conflict has heavily damaged infrastructure across BF. Attacks on water points are common, and according to UNICEF, results in increased water scarcity, with some regions losing regular water access for up to 223,000 persons.